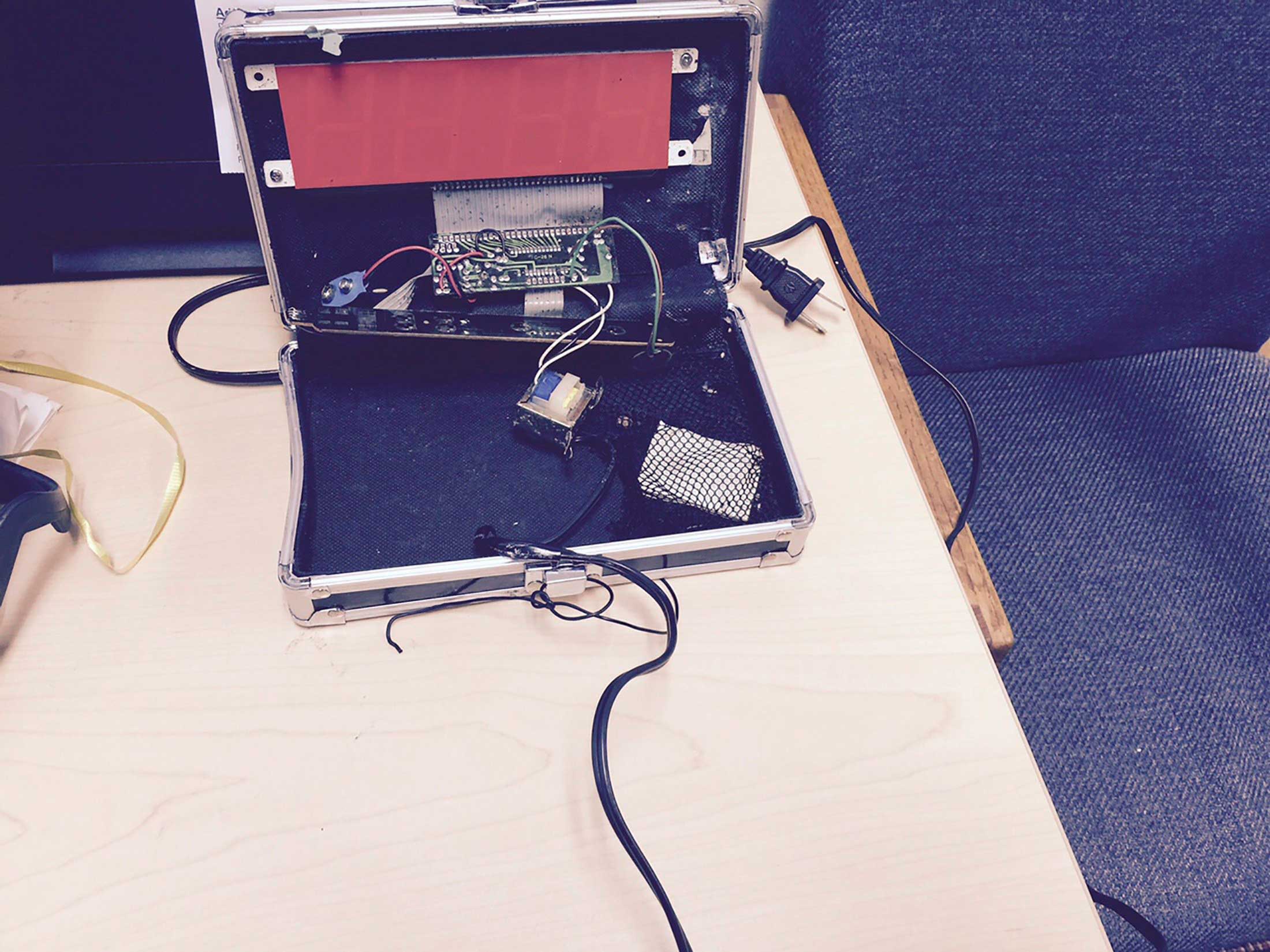

Ahmed Mohamed is the least scary person in the world—or at least the least scary one you’re likely to meet on any given day. He’s a 14-year-old ninth-grader at MacArthur High School in Irving, Texas—sweetly nerdy, slightly awkward, and here’s what he did on September 14: He brought a digital clock to school, one he’d built himself, so he could show it off to his science teacher.

Here’s what he didn’t do on September 14: bring a bomb to school.

That didn’t stop Ahmed from being interrogated, arrested, handcuffed, fingerprinted and booked for being in possession of what, to some, looked like an explosive device. Oh, and there were mug shots too—mug shots of a kid who’s still three years away from having his senior picture taken.

By now the story of Ahmed is everywhere, with predictable—and justifiable—questions being raised about whether his Arabic name and appearance brought him a level of scrutiny another child wouldn’t have gotten. Predictable too is the Twitter storm (using the hashtag #IStandWithAhmed) the incident has triggered, with politicians, including President Obama and Hillary Clinton adding their 140-character voices. (“Cool clock, Ahmed,” the President’s Tweet read. “Want to bring it to the White House. We should inspire more kids like you to like science. It’s what makes America great.”)

But if there’s a certain familiarity and slacktivist opportunism to the injustice-outrage cycle, there’s something troublingly different about Ahmed’s case. He is exactly—exactly—the kind of kid the country knows it needs: inquisitive, inventive and, most important, innately drawn to the STEM track—science, technology, engineering, and math.

And now he has had the daylights scared out of him because the clever thing he built scared the daylights out of grown-ups who should know better. Ahmed’s engineering teacher, who did know better, was aware of the effect the little invention might have.

“He was like, ‘That’s really nice,’” Ahmed told the Dallas Morning News. “‘I would advise you not to show any other teachers.’”

Americans, for all our technological savvy, have a history of being rattled by science, most memorably on Oct. 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite. Sputnik was about as big around as a beach ball, circled the Earth every 98 minutes and was equipped with the diabolical power to, well, beep at us as it flew by.

But never mind. It was Russian, it was space-y, and therefore it was spooky. Americans responded by digging fallout shelters in backyards, holding air raid drills in schools and generally freaking out, in the firm belief that death was surely about to rain down on us from space. (Sputnik, for its part, burned up in the atmosphere three months after it was launched, without ever incinerating America.)

But if Americans hunkered down after the great Sputnik humbling, they also wised up. President Eisenhower knew a space race was coming and in fact was pleased that the Soviets had jumped first, since they made it acceptable for any other nation to launch all the reconnaissance satellites it wanted. More important, to ensure that the U.S. was ready for the challenge that faced it, he pressed for passage of what became known as the National Defense Education Act. The preamble of the law, which was enacted in 1958, read in part:

“The Congress hereby finds and declares that the security of the Nation requires the fullest development of the mental resources and technical skills of its young men and women…The present emergency demands that additional and more adequate educational opportunities be made available. The defense of this Nation depends upon the mastery of modern techniques developed from complex scientific principles.”

Certainly, the Soviet threat was real. Sputnik might have been harmless, but the rocket that launched it—the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile—wasn’t. So the air raid drills and all the rest weren’t entirely crazy. But it was the education act that parlayed merely not-crazy into something bigger.

America faced another mortal threat on Sept. 11, and while we overreacted then too, a lot of other things made sense. Unattended parcels and suspicious shadows in airport x-rays do pose potential threats, and we’re all a little safer if we cooperate to confront them. But where we exhibited smarts after Sputnik, we’ve found mostly cynicism since 9/11.

Our reaction to the attacks of 14 years ago is more reminiscent of our reaction to Pearl Harbor. Sure we fought—and won—the war. But we also rounded up 120,000 Japanese-Americans and locked them in internment camps because unlike German-Americans—whose ancestors also came from a country with which we were at war—we could identify them on sight.

So, similarly, we look out of the sides of our eyes at the student with the brown skin and the Arab name, put him in cuffs for building a toy and ask questions later. Reasonable people may differ on whether a white boy with an Anglo name would have gotten the same treatment, but the very fact that it’s a reasonable question should cause us concern.

Ultimately, it took an education-driven America only 12 years after Sputnik to achieve the goal it had set for itself, putting astronauts on the surface of the moon. As it happens, the average age of the young engineers manning the Mission Control consoles the night Apollo 11 landed in the Sea of Tranquility was 26. That means they were only 14—Ahmed’s age—when the Sputnik scare occurred.

Getting arrested for their inventiveness was not a hurdle the men of Apollo had to overcome to play their part in history. The same, sadly, was not true for Ahmed.

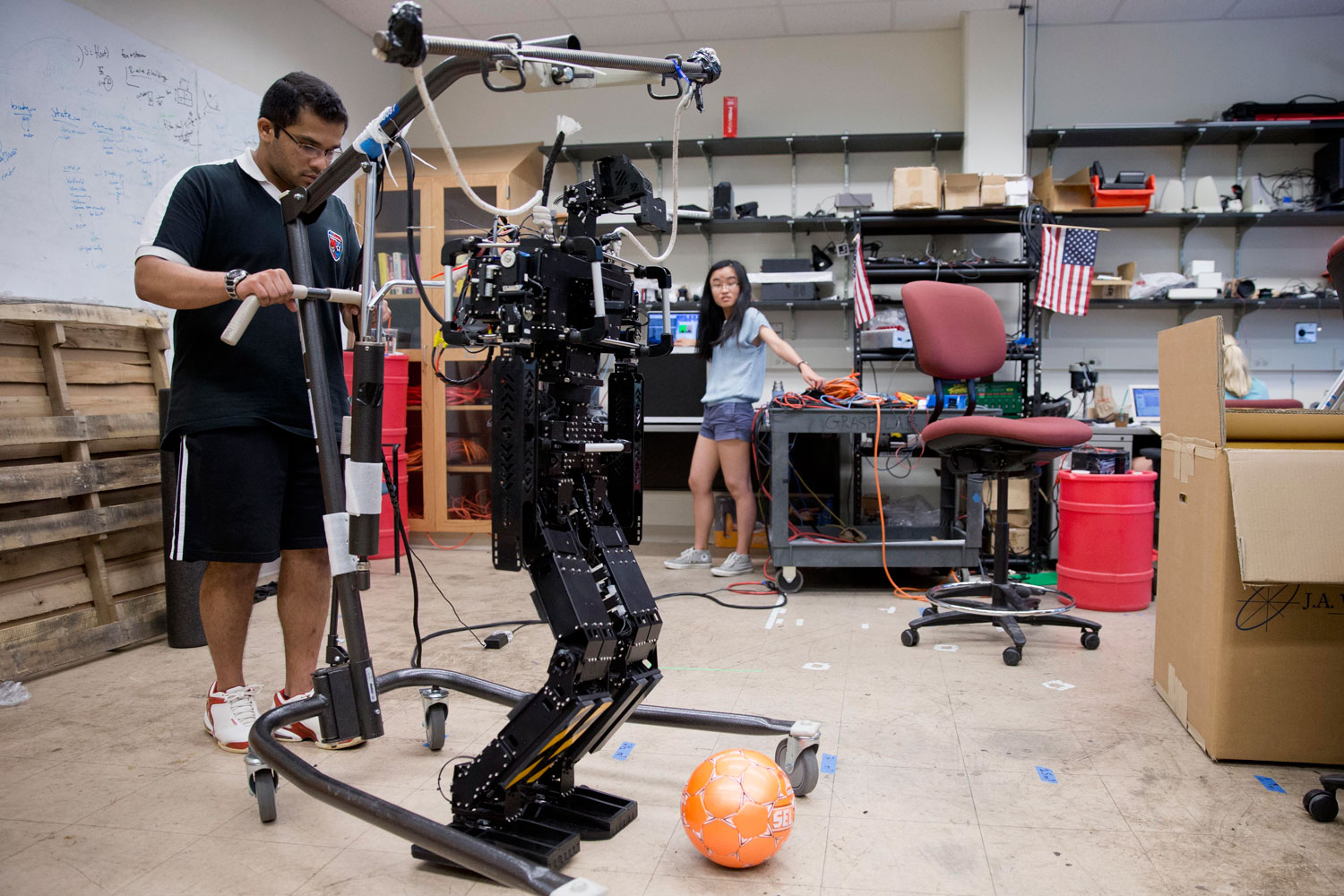

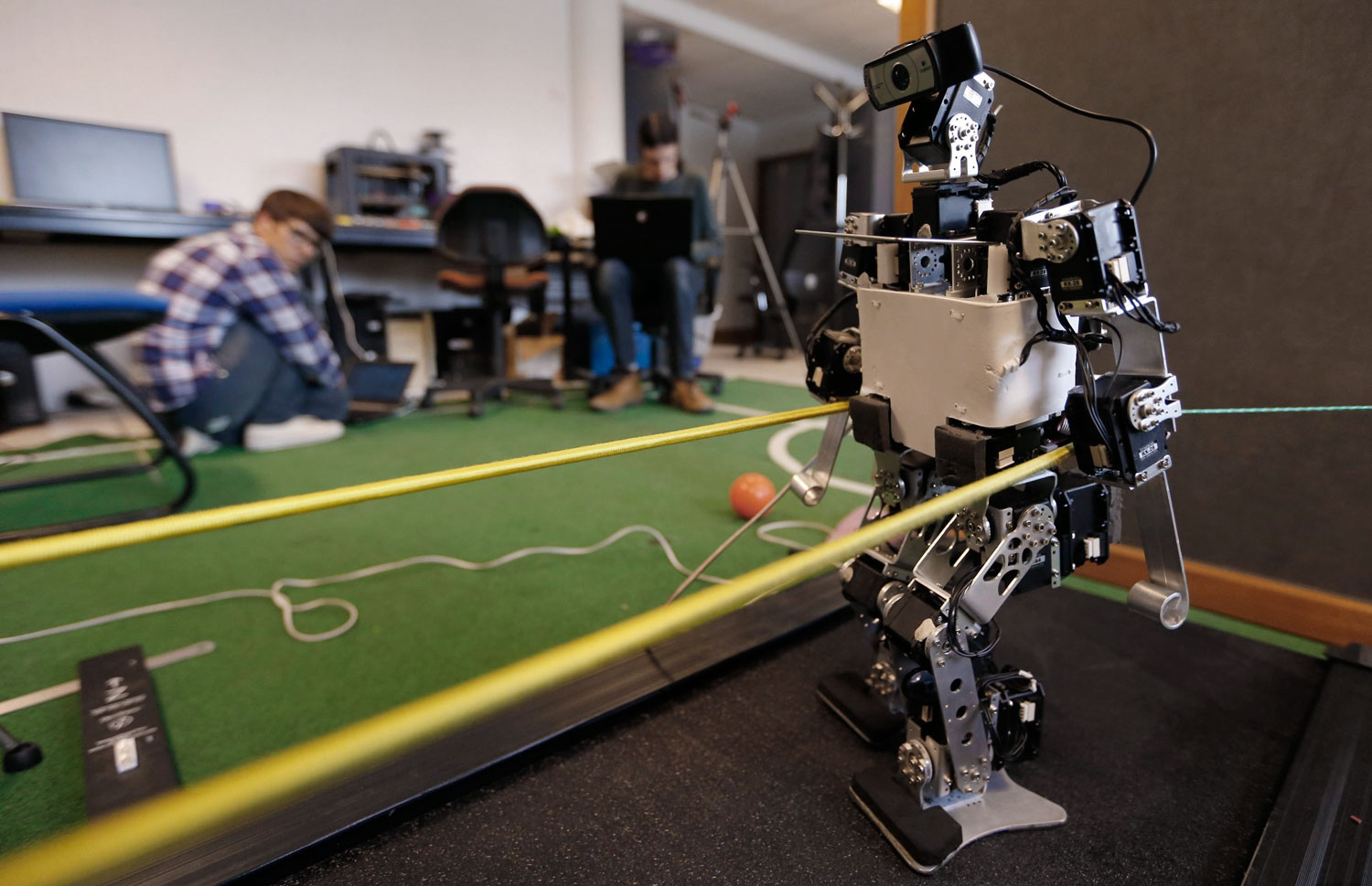

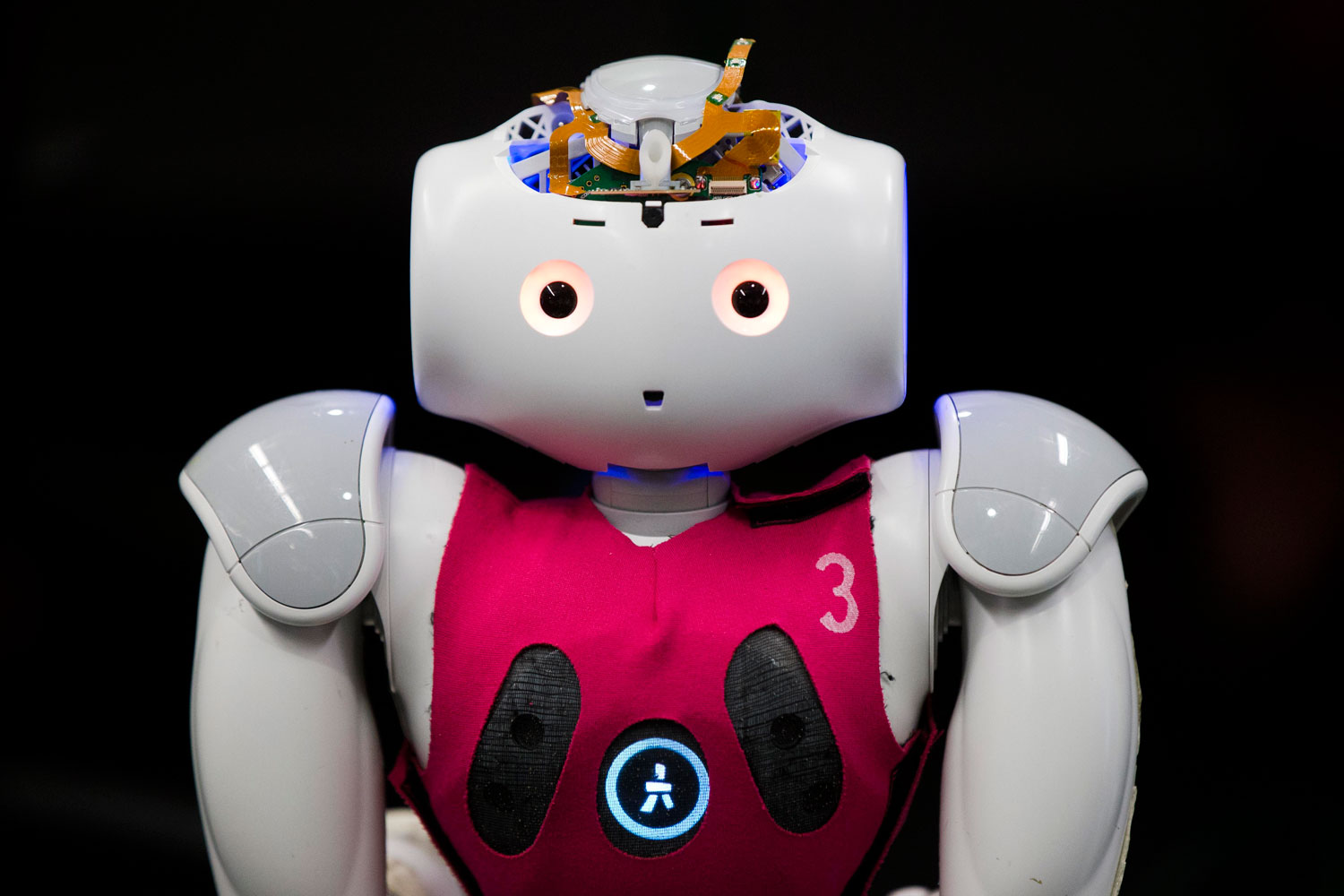

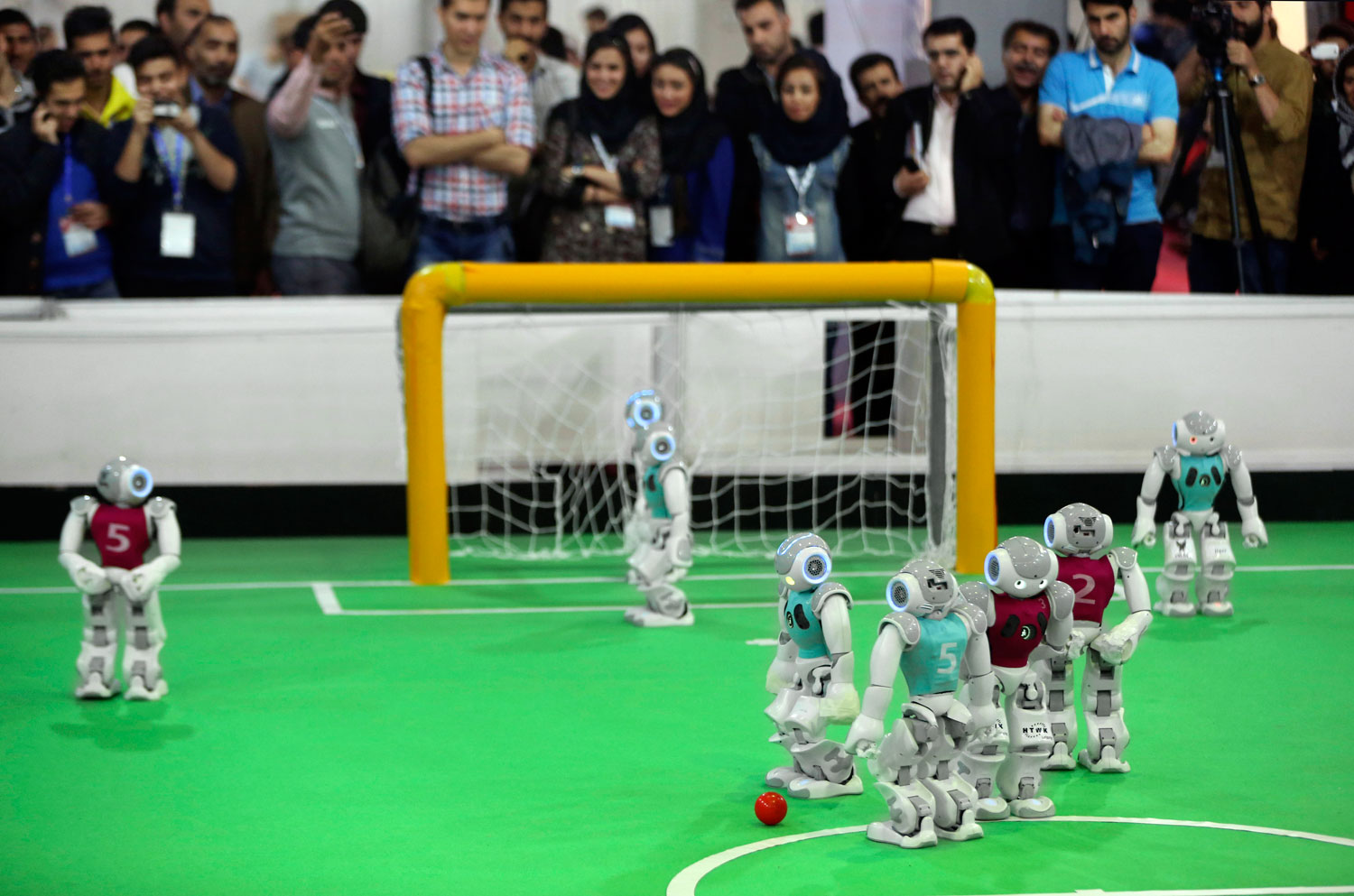

These Robots Have Their Own World Cup

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com