Each morning since the start of September, when he arrived on the Turkish coast with plans of escaping to Europe, Hasan Musally, a 42-year-old welder from Syria, has come to Fener Beach to practice swimming. He starts each time by looking out at his destination—the northern tip of Kos, a Greek island about six km (3.7 miles) away—and then he swims toward it through the choppy waters, going as far as he can before the fear and the pain in his lungs makes him turn back. Two weeks into this daily ritual, Musally feels he can just about make it across.

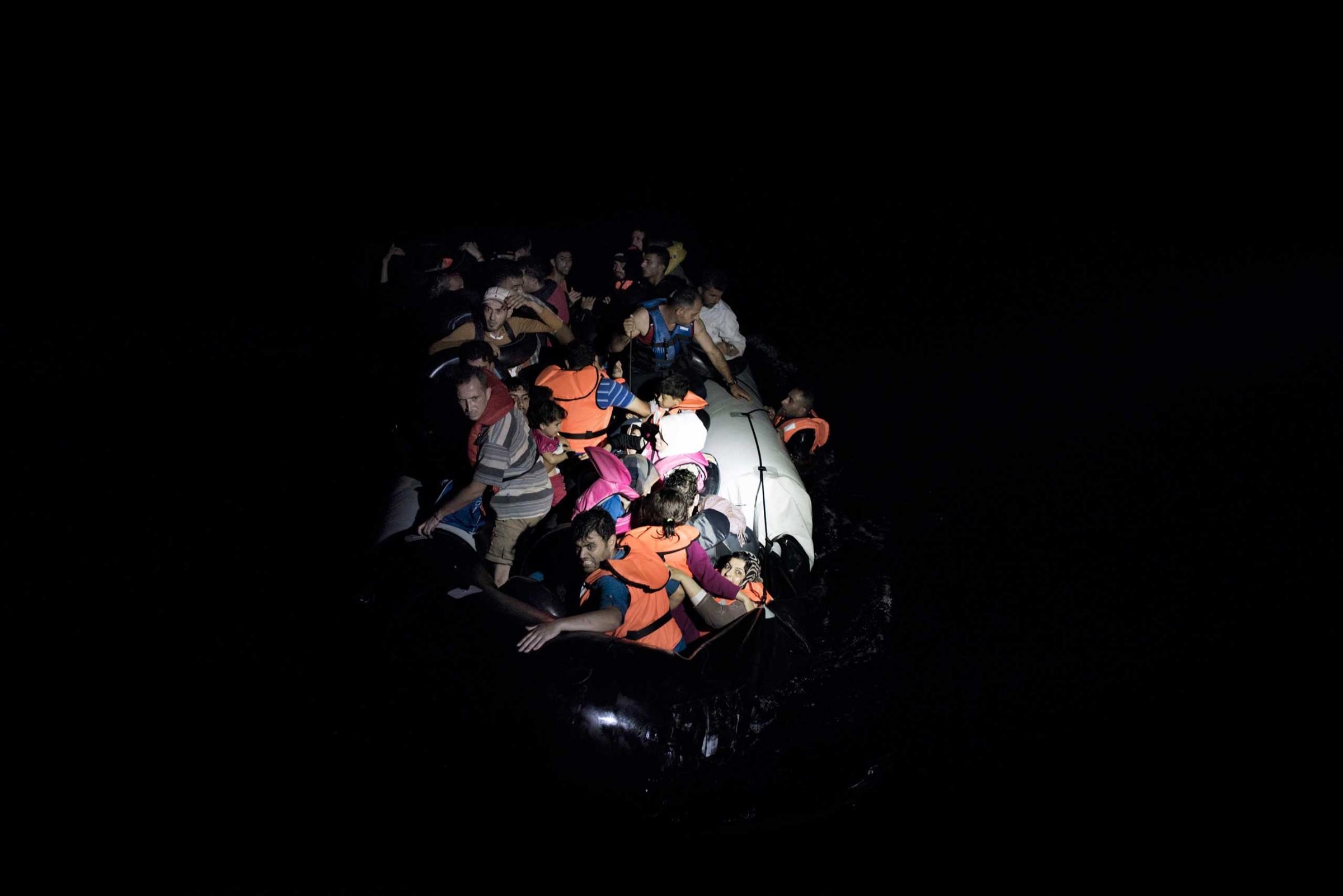

“But wind is a big problem,” he said on a recent evening, when the gusts prevented him from attempting to swim the entire channel for the first time. As the seasons change, the waves are also getting higher, and even migrants who can afford to pay human traffickers or to buy their own inflatable boat for this journey often fail to make it across. On Sept. 13, 34 migrants drowned in the Aegean Sea after their dinghy deflated in the water, joining more than 2,000 others who have died trying to cross to Greece this year. Yet up and down the western coast of Turkey, there are still hundreds of thousands of migrants preparing for the trip to Greece—and according to Turkish authorities, they are resorting to ever more desperate means of doing so.

“They swim, they paddle, they buy a little outboard motor, with maybe three or four horsepower, and see what they can do,” says a senior maritime official in the Turkish seaside town of Bodrum, who agreed to discuss the migrant crisis only on condition of anonymity. “We found one couple from Syria who tried seven times to go across. Every time they failed.” The Turkish coast guards would turn back their boat, or human traffickers would simply rob them. But each time the couple would try again.

Through the window that faces his desk, the official can see a vast harbor crowded with the sailing and fishing boats, which wealthier migrants from Syria have used to get safely across the waters to Greece. (Some have paid as much as $4,000 to hide in the hold of a luxury yacht for a journey of no more than 15 km (9.3 miles), said one local businessman who helped arrange such a crossing.) But the poorest asylum seekers—not Syrians, but more typically Afghans or migrants from other parts of South and Central Asia—have meanwhile been turning to cheaper and deadlier methods.

Their logic, though desperate, is simple enough: They believe Germany has opened its doors to all asylum seekers, and most of them seem unaware—or unwilling to accept—that those doors are quickly closing. On Monday, about a week after easing its own migration rules in order to welcome Syrian refugees, Germany imposed emergency controls along its border with Austria, and the government announced that it has reached “the limit of its capabilities” in managing the influx of migrants coming across that frontier. “It is not just a question of the number of migrants, but also the speed at which they are arriving that makes the situation so difficult to handle,” Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel told a German newspaper on Sunday, when 13,000 migrants arrived in Munich over the course of 24 hours.

But whether or not the Germans are ready, many others are already on their way from the Turkish coast, having interpreted Berlin’s initial hospitality as proof that Syrians—if not all migrants—are welcome to settle in Germany. Among them is Mazin Awad, a 47-year-old asylum seeker from Damascus who has been camping outside a mosque in the center of Izmir, Turkey’s third largest city, for the last two weeks. Last week he saw the footage of cheering crowds greeting asylum seekers in Munich, and he has since had trouble understanding why the German government cannot just send a bus to pick him up. “If Germany takes people,” he asks, “why not take us from here?”

It is a common sentiment among the dozens of down-and-out migrants TIME spoke with on the Turkish coast last week. On social networks, a growing movement has emerged among them calling for unrestricted passage for Syrian migrants to Europe. One Arabic-language Facebook group—“We Are Just Passers-by”—is urging Syrians to gather at Turkey’s land border with Greece and demand safe passage into the European Union.

That would allow many thousands of migrants to avoid using those overcrowded boats—or more even perilous methods—to get across. But the E.U. isn’t likely to be so generous. In Hungary, Poland and other Eastern European nations, governments have called for member states to stop the migrants before they enter the E.U. Hungary has gone so far as to declare a state of emergency, sealing off its southern border and detaining migrants who cross it illegally. In a warning to his peers last week, Polish President Andrzej Duda said accepting asylum seekers would only encourage others to leave their homelands in a “vicious circle” of migration to Europe.

That doesn’t seem far from the truth on the Turkish coast. Though Syrians still make up the largest share of people headed to Greece by boat, they have been joined by at least as many migrants from impoverished or war-stricken countries in Asia and Africa. In Bodrum, at the edge of the main bus terminal, hundreds of men from Pakistan have been camping out for weeks on a craggy slope, sleeping on scraps of cardboard with no protection from the sun. One of them, a 38-year-old from Lahore named Mohamed Rizwan, says he and several of his friends intend to buy an inflatable paddleboat and row it all the way to Greece. “We have no money for food,” he said. “How can we buy a motor?”

Though still verging on the suicidal, their plan for getting to Europe is at least a better one than swimming. The winds on the Turkish coast were fierce last week, and temperatures are steadily dropping. But Musally, who hails from the Syrian city of Aleppo, has no intention of going back to Istanbul, where his wife and three children are waiting for him to make it to Germany. Earlier this month, on the beach where he’s been honing his breast stroke, the body of a three-year-old Syrian migrant named Aylan Kurdi washed ashore, and Musally witnessed the ensuing commotion as police and foreign journalists descended on the scene of the tragedy. That, too, did not dissuade him from going in the water. “Allah,” he said. “Allah will protect us. That is what I hope.”

(As of Tuesday, when a reporter last spoke with him on the phone, Musally had yet to attempt the crossing. The winds were still too high.)

These Photos Show the Massive Scale of Europe’s Migrant Crisis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com