For your reference, TIME has compiled a guide to buzzwords, terms and phrases cropping up in the 2016 presidential campaign. We’ll update this throughout the silly and serious seasons that voters weather on the long march to November 2016.

anchor baby (noun): (offensive) used to refer to a child born to a noncitizen mother in a country which has birthright citizenship, especially when viewed as providing an advantage to family members seeking to secure citizenship.

See: terror baby

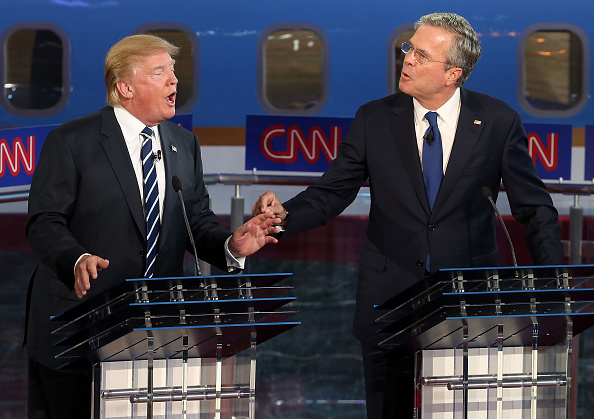

Jeb Bush found himself asea in criticism after he used the term anchor baby in August, a phrase that Donald Trump invokes unapologetically. Bush said he was referring to “birth tourism” by Asian mothers, though for years the term has been used to stereotype Hispanics, often by proponents of strict immigration laws. Many see the term as a slur that suggests Hispanics would have a child simply as a means to an end.

bigly (adverb): with great force; violently; firmly; boastfully.

See: things Donald Trump says

Dictionary.com experienced a spike in lookups after Donald Trump announced his candidacy in June and declared, repeatedly, that things were happening or would happen “bigly.” (Outfits like the Federal News Service transcribed his talk as “big league,” though that makes little sense in sentences like “Iran is taking over Iraq, and they’re taking it over big league.”) Tweeters mocked him for thinking it was word—another to join the ranks of refudiate and strategery—but the rarely used word that can also mean “loudly” or “proudly” dates back to the 15th century.

democratic socialism (noun): a form of socialism pursued by democratic rather than autocratic or revolutionary means, esp. by respecting a democratically elected legislature as the source of political change.

See: the political philosophy embraced by Democrat Bernie Sanders

This definition comes the Oxford English Dictionary, while Dictionary.com explains the political philosophy as a form democracy in which “the ownership and control of the means of production, capital, land, property, etc.,” is communal. The more burning question is what this term means to Sanders who has answered that question by saying things like: “Democratic socialism is taking a hard look at what countries like Denmark, Sweden, Norway …. have done.” Debbie Wasserman Schultz, chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee, has been asked several times what the difference between a Democrat and a democratic socialist is—and has so far sidestepped any answer.

flip-flopper (noun): a politician who changes his or her mind or position on something.

See: criticism of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and almost every other candidate at some point

This one is a campaign-season perennial that is sticking fast to Walker as an early front-runner lags in the polls. The term has been used to described wishy-washy politicians since at least 1890 and comes from a much older phrase: flip-flap, which first described things that “go” flip-flap—like a sheet in the wind—then a frivolous woman and later a kind of “rollicking” somersault that involved throwing one’s hands and feet over and over each other. (While some have wondered whether Walker is the “biggest flip flopper” out there, there’s little question which American politician has been associated with the biggest flip-flop.)

-ghazi (suffix): added to a word to suggest and actual or alleged controversy, sometimes used ironically to suggest that the scandalousness of an event is being overblown.

See: ballghazi, bridgeghazi, emailghazi and other forms

During Clinton’s time as Secretary of State, terrorists attacked a U.S. outpost in Benghazi, Libya, leading to the death of four Americans. Controversy over the event—particularly over how Democrats like Clinton anticipated and reacted to it—spawned another political suffix that appears to have staying power. The usage of this one reflects how people have been divided over exactly how much wrongdoing (and what kind) there was in the Benghazi. For some, any “-ghazi” is a straightforward scandal; for others it might be a scandal in which, say, allegations about governments cover-ups have gone beyond the scope of reason.

kids’ table (noun, slang): a (pejorative) name for a event, group or issue which is not paid as much attention as competing people or things.

See: “happy hour” debate

When the Republicans had their first face-off on Aug. 6, seven candidates who didn’t poll well enough for prime time were assigned to the “undercard” or “JV” or “second tier” debate. The “kids’ table” often crops up as a metaphor when people feel sidelined in politics, the suggestion whoever is seated there doesn’t have much important to say. It’s been invoked those who feel candidates aren’t paying enough attention to issues they care about, activists who have trouble advancing their causes and talking heads. “We’ve arrived at the adults’ table,” an LGBT rights activist said in 2014 after President Obama spoke about gay rights in a high-profile speech. ” We’re no longer at the kids’ table.

loser (noun, slang): an unsuccessful or incompetent person.

See: things Donald Trump says

Summing up people as “losers” is one of of Trump’s calling cards. Politicians often stick to targeted, euphemistic criticisms rather than the totally dismissive variety, but that’s just one of many ways Trump has defied the rhetoric of typical presidential candidates. And he’s not the only one who was veered out of elder-statesman territory. As Trump tore out in front of more experienced office-holders in 2015, some were inspired to call him things such as a “cancer,” a “carnival act” and “narcissist,” while Hillary Clinton stuck to more conventional language when describing his ascendancy as a “unfortunate development.”

low-energy (adjective): below average in the amount, level, or degree of power one displays or exerts.

See: things Donald Trump says

In the second Republican debate, the candidates we’re asked what their Secret Service code names would be, and Jeb Bush, standing next to Donald Trump on stage, answered, “Eveready,” noting that it was a “high-energy” answer. Trump has repeatedly accused Bush of being a “low-energy” candidate, an insult with connotations of Bush being un-macho, stiff and boring—especially compared to the reality TV star. His father, George H.W. Bush, had his own “wimp factor” problems that this new generation of insults may be conjuring for older voters.

-mentum (suffix): added to the name of a politician to suggest he or she is gaining popularity or attention as a presidential candidate.

See: Bernie-mentum, Biden-mentum, Trump-mentum, Marco-mentum, Hill-mentum, other forms.

In physics, momentum describes how much motion a moving body has, and former Sen. Joe Lieberman deserves much of the credit for turning the suffix into political jargon that can be attached to anything that gains or leads in polls. Running for president in 2004, he couldn’t resist the pun of describing his own rhyming Joe-mentum, which some have revived to describe support for the candidacy of Vice President Joe Biden (though many Biden supporters prefer Biden-mentum to avoid recalling Lieberman’s failed campaign). Mentum may also be used (in jest) to describe a stalled campaign.

servergate (noun): the controversy related to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s decision to use personal email accounts on a privately maintained server when conducting official business during her time in office.

See: Watergate and countless other forms

A break-in in 1972 led to the first resignation of an American president and to one of the most productive political suffixes of all time. Anything with a whiff of scandal is ripe for having –gate tacked onto the end, whether it’s an object (like a computer server), a country (like Iran) or a body part (like a nipple). There is debate over how the historic hotel, office building and former Democratic HQ got its name, perhaps from a “water gate” that marked the spot where the Chesapeake and Ohio canals meet Washington’s Potomac River.

The Donald (noun): nickname for Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

See: things Ivana Trump says

It might seem like Donald Trump is the type of brash, confident man to put a definite article in front of his own name—as if to imply that there is only and will only ever be one Donald of consequence. But the nickname comes from his former wife, Ivana Trump, who would often put definite articles in front of people’s names as she was learning English (which, she told the Washington Post, is her fourth language). The nickname came to light in a 1989 Spy magazine story on Ivana, “‘The Donald’ just slipped off the tongue,” she told the Post, “and now it seems to be making its ways to the political history books.”

Send your suggestions for other entries to the author via Twitter at @katysteinmetz.

Read Next: 15 Forgotten English Words You Should Know

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com