A couple of hours after midnight on Saturday, a cruise ship called the El Venizelos docked on the Greek island of Lesbos, near the western coast of Turkey, and opened its gangplank to allow the migrants inside. The light from within the enormous vessel cast a glow on their tired faces — nearly 2,500 of them, mostly from Syria and Afghanistan — and they packed their bodies tighter at the edge of the dock, afraid that they might be left behind.

The bulk of the El Venizelos, an aging liner that once ran luxury tours of the Mediterranean, embodies the sheer scale of Europe’s refugee crisis. In the middle of August, when the influx of migrants peaked at several thousand per day, the Greek government chartered the ship to help ferry them to the mainland from the islands where they come ashore. But while the ship is large enough to fit the population of a small town, the dozen journeys it has made since Aug. 19 have failed to unburden even the island of Lesbos, which has become one of the most crowded and volatile outposts along the migration route to Western Europe.

“We are not enough to fix this,” said Antonis Pikoulos, the ticketing agent for the ship, as he stood on the dock and stared in amazement at the throngs waiting desperately to board, hundreds of women and children among them. “In one trip we can move 2,500 out from here,” he added. “But 3,000 more arrive every day.”

For each migrant who bordered the ship that night, five others remained stuck on Lesbos, sleeping on its roads and promenades and building tent camps in parks and outside the gates of the port. On Saturday evening, as the El Venizelos was preparing to return to Lesbos to pick up its 12th haul of migrants, hundreds of them tried to rush the line of riot police guarding the docks, some throwing stones. Another skirmish broke out there the following day, and several people were badly injured after police used tear gas, batons and stun grenades to subdue the stampeding crowd. Since then, Athens has deployed two more detachments of riot troops to guard the port, while soldiers are rushing to build detention camps to house the migrants away from the tourist districts on the island.

On Saturday, the loading process of the El Venizelos passed without violence, though the atmosphere remained tense. Greek riot troops in fatigues marched along the tight ranks of migrants, shouting at women and shoving men who stepped out of line. “We’re working here,” one officer barked at a reporter who tried to photograph the scene. “This is not a place for journalists.”

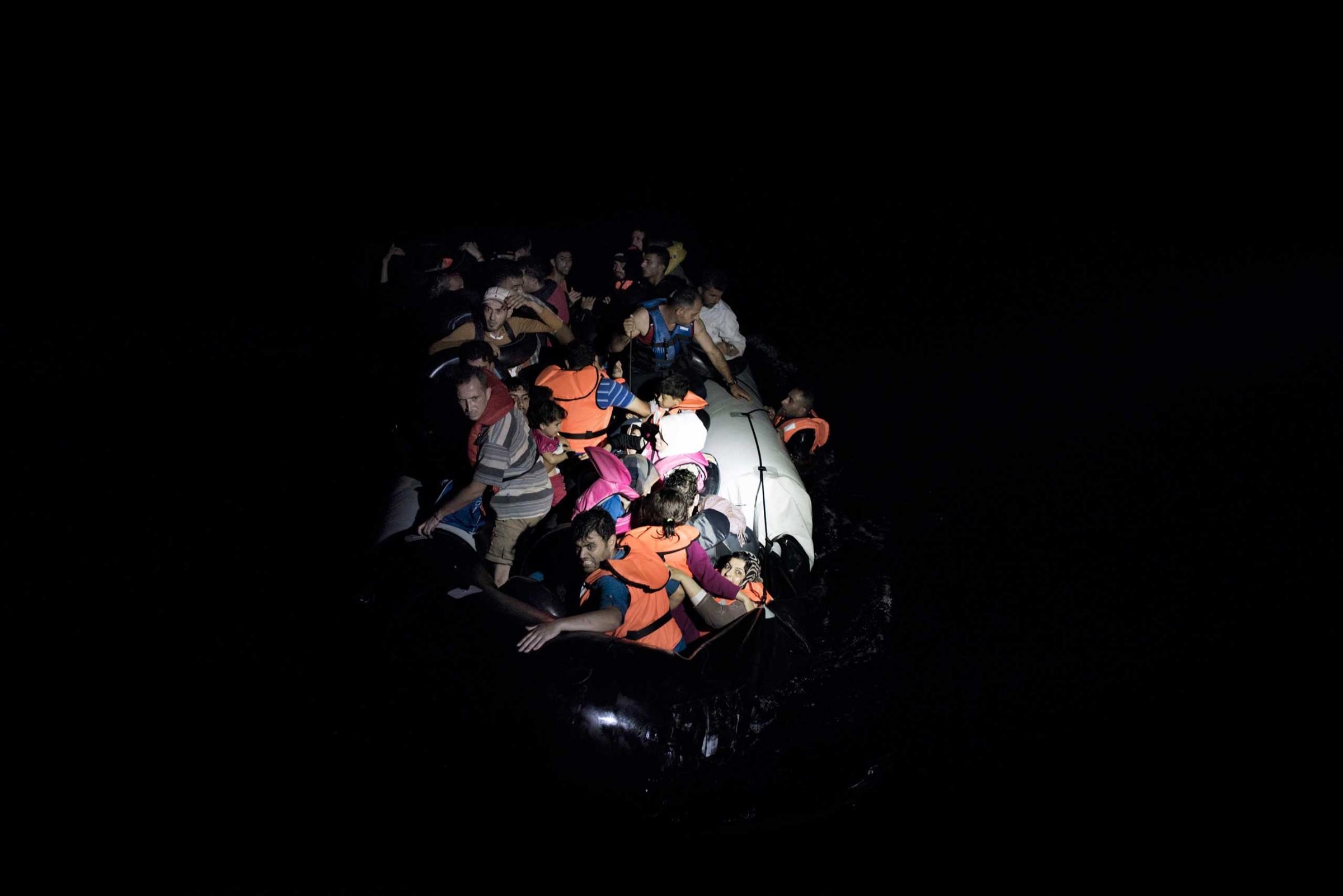

Alaa Alsheikh Ibrahim, a 29-year-old migrant from Damascus who holds a degree in mechanical engineering, stood mutely in the crush with nothing but the clothes on his back. Four days earlier, he had been forced to throw all of his possessions into the Aegean, he said, when he spent about 12 hours lost at sea inside a small rubber boat stuffed with 42 fellow Syrians. Normally, the crossing from Turkey to the Greek islands takes no more than an hour or two. But Ibrahim’s boat was unlucky: the wind blew it off coarse, and it began to take on water. “We all thought it was the end,” he recalled.

On reaching the shore, he continued traveling with six of those compatriots he met during that crossing — “my boat friends,” he called them — and they were all a bit nervous about going back out to sea on Saturday on the El Venizelos. But the ship’s amenities made the day the most pleasant of their travels so far. Ibrahim, who speaks fluent English, volunteered to help the ship’s crew communicate with Arabic-speaking passengers, and his reward for this work was a private cabin. “It was the first shower I’ve taken in 10 days,” he said with a smile.

Few are so lucky. Even though a ticket onto the ship costs the migrants about €50 ($56) apiece, they are generally not allowed to use any of the ship’s roughly 1,600 beds. So most of them simply curl up on the floor or in soft chairs throughout the vessel; those who cannot find a patch of carpet sleep right on the deck beneath the stars.

This is still far nicer than the welcome they’ve received on the islands in recent weeks. Most hotels have been refusing to rent rooms to migrants, and human-trafficking laws prohibit buses and taxi drivers in Greece from selling them rides. That forces most to walk for at least a day across the length of the island before reaching the police and port authorities, which take another few days to issue documents the migrants need to travel on.

In her dusty shop window beside the port, Glykeria Kontaxaki, a travel agent who still has a squeamish aversion to the sight of the migrants, now spends her days issuing ferry tickets to a seemingly endless line — about 400 every day, she says — and that’s only at her branch of the local travel bureau. “The Syrians mostly seem educated,” she observes from the weeks she’s spent in their company at work. “They know great English, and they are very polite … But with the others it’s a different story,” says Kontaxaki, rattling off a list of South and Central Asian nations who seemed to have made a bad impression.

These Photos Show the Massive Scale of Europe’s Migrant Crisis

Among the migrants themselves, such prejudices have also been a point of friction, and many seem to have brought along to Europe the social and religious rivalries that divide communities across the Middle East and Asia. Around noon on Friday, a massive brawl broke out between Afghans and Syrians near the main port of Lesbos, and after breaking it up, police forced all of them back into the streets and moved hundreds of people from the two nationalities into separate refugee centers. The one for Syrians is an open camp conveniently located next to a large supermarket and a short walk from the port. The one that houses Afghans and other Asians is farther inland, at the end of a desolate road, and has high barbed-wire fences that smack of a prison even if its inhabitants are mostly free to come and go as they please.

Antonios Gkagkarellis, the police lieutenant who was in charge of the camp for Afghans on Saturday afternoon, says that all the migrants have mostly been gracious toward locals, and have been especially careful to hide any ill will toward Greek officials and police. “We hold the keys to Europe and we give it to them,” he says. “So with us they behave better.” But among themselves, the migrants do not always observe such bounds of etiquette. “They have big problems with each other,” says Gkagkarellis.

Many Syrians TIME speaks with voice the same complaint against the Afghans, and it was not religious or cultural in nature. They simply feel the migrants from impoverished nations like Afghanistan are trying to hitch a ride to Europe on the misery of refugees now fleeing Syria. “They all say they are Syrians so Germany will take them,” complains Mohammad Yusef, a 26-year-old music-video producer from Damascus.

For most of this summer, Germany and other wealthy European states have prioritized the intake of migrants from Syria, because its civil war has been more devastating than conflict zones in other parts of the Muslim world. According to authorities in Hungary, another transit country along the migrant trail through Europe, about a third of asylum seekers who claim to be Syrian are in fact lying about their nationality to improve their chances of getting the legal and financial benefits of refugee status.

But such gripes have brought deeper divides to the surface, especially as thousands of people from vastly different cultures and social strata are forced to travel side by side and, in effect, to compete for the finite hospitality of Europe’s wealthy states. Ibrahim, the mechanical engineer, suspects sectarian issues will become more pronounced among the migrants in the towns and neighborhoods where they eventually settle. “Now they are busy,” he says. “They have no time to think about religion, about who is Sunni and who is Shia. But it’s still there. You can’t just leave all that behind.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com