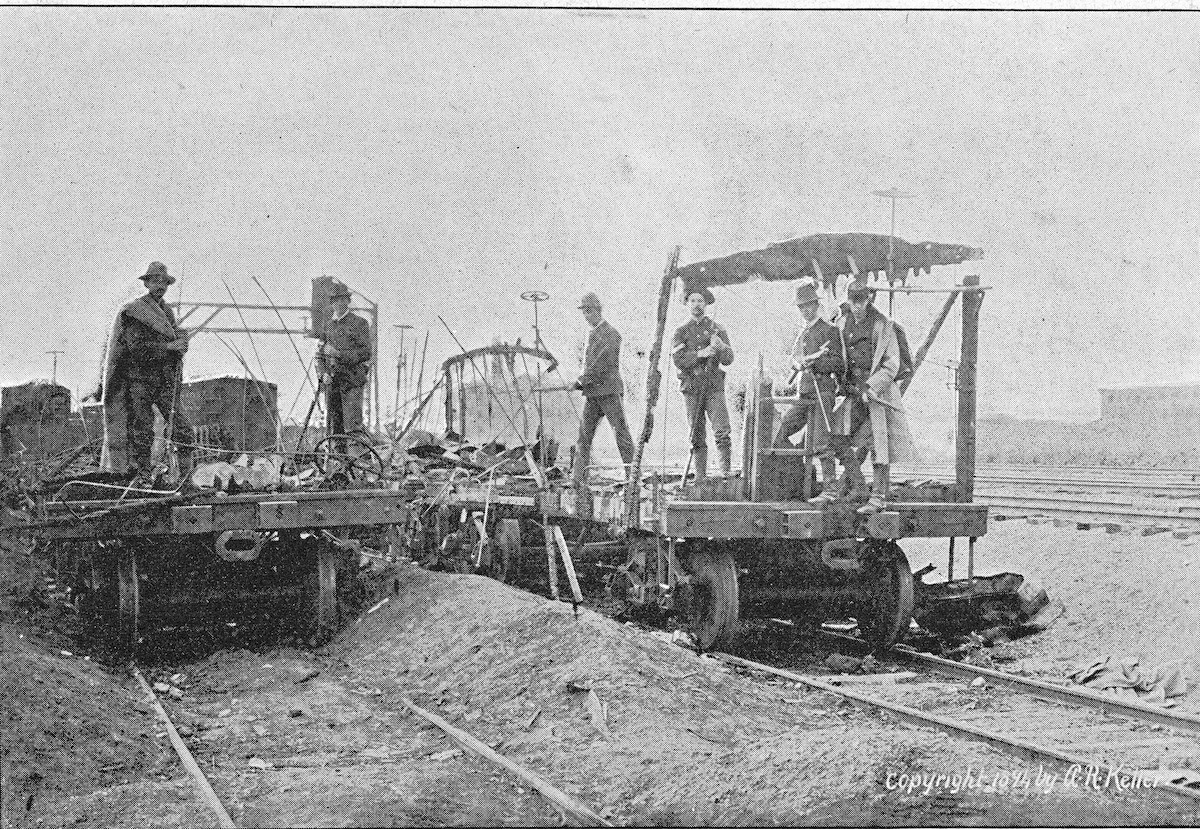

It’s little more than a day off for shopping now, but when Labor Day was first observed, it wasn’t all fun and back-to-school sales. Its passage as a federal holiday, in 1894, was a sort of peace offering from President Grover Cleveland for the killing of a dozen or more striking railway workers.

The strike began as unrest in the Illinois town founded by George Pullman, creator of the railroad sleeping car. The town, just outside Chicago, had been built as a utopian home for Pullman’s workers, but the utopia was designed to serve Pullman above all others, according to PBS. “Its residents all worked for the Pullman company,” PBS notes, “their paychecks drawn from Pullman bank, and their rent, set by Pullman, deducted automatically from their weekly paychecks.”

From 1880 to 1893, all seemed well in Pullman (the town), until an economic depression prompted Pullman (the man) to cut employees’ wages — even though their rents remained the same. The workers walked out. In solidarity, members of the American Railway Union (founded, per TIME, by “fiery Socialist Eugene Debs”) took up the cause, and its 150,000 members refused to work on trains carrying Pullman cars, prompting a nationwide transportation nightmare.

It was, according to The Atlantic, America’s first true nationwide strike — and a major milestone for the labor movement. But it didn’t end well, for anyone. President Cleveland, under pressure from the railroad industry and the U.S. Postal Service, whose mail trains had ground to a halt, declared the strike a federal crime and sent troops to break it. David Ray Papke, the author of The Pullman Case, describes the rioting and arson that ensued, and was suppressed; while death counts vary by source, TIME called it “one of the bloodiest strikes in U.S. history.”

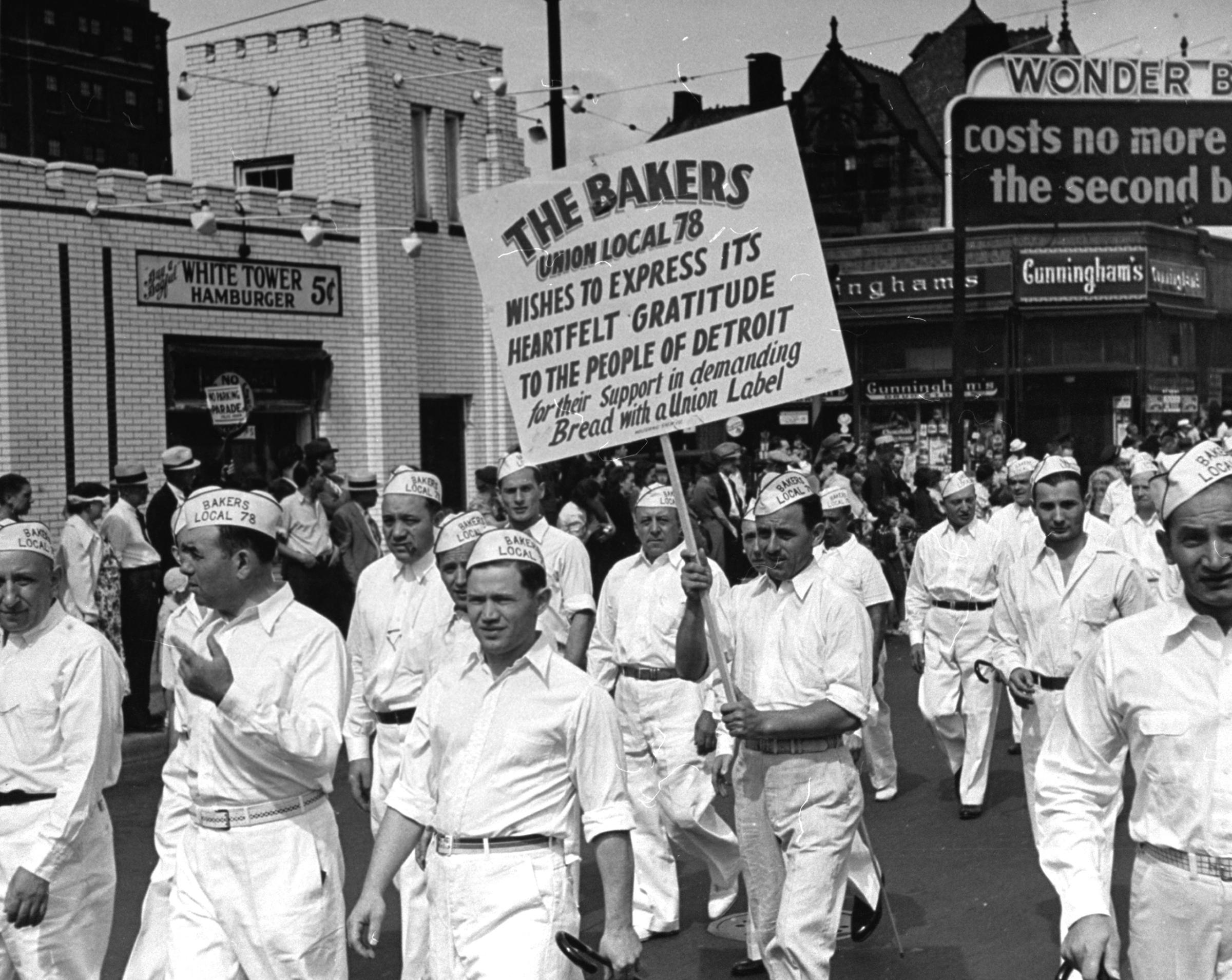

Labor Day Parade, Detroit, 1938

While the strike came to an abrupt end, and Pullman employees promised never again to unionize, Cleveland’s popularity suffered, especially among the labor movement’s working-class core. Making Labor Day a national holiday was the president’s election-year attempt at an olive branch, per PBS, although it didn’t succeed in winning him another term.

Over time, however, as tensions eased between unions and the establishment, the holiday came to have less to do with labor leaders than with retail figures.

“[W]hile the day still honors the U.S. workingman,” TIME noted in 1962, “it has evolved over the years into a much more significant date in the life of the American consumer. No seasonal divide so sharply separates the living and buying patterns of men, women and children across the land.”

In its 1962 roundup, TIME summarized Labor Day’s implications in commercial, not historical, terms: American consumers switch from gin to whiskey, stock up on light bulbs, and invest in new carpets and furniture. White clothing, of course, disappears from store shelves — and even white accessories sell “at fire-sale rates.”

In supermarkets in the early ’60s, Labor Day also heralded an increase in sales of stew meat, and a decline in cold cuts and hot dogs. TIME lamented: “…down goes the lowly frankfurter; after Labor Day First National Stores, a chain of supermarkets in New England, New York and New Jersey, sell 50% fewer frankfurters and 65% fewer hot dog rolls.”

Read the full story from 1962, here in the TIME archives: The Great Divide

Correction August 29

The original version of this story misstated the year in which the photo above was taken. It was taken in 1894, not 1984.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com