Grandparents are (almost) as old as humanity, but Grandparents Day in the United States is less than four decades old. And while the name evokes warm-and-fuzzy celebration of family, the tradition was established to combat a decidedly modern phenomenon.

It was Sept. 6, 1979, that President Jimmy Carter issued an official proclamation designating the first Sunday after Labor Day as National Grandparents Day, in the hope that society could learn from “grandparents whose values transcend passing fads and pressures, and who possess the wisdom of distilled pain and joy” and because “our senior generation also provides our society a link to our national heritage and traditions.”

The proclamation followed on the heels of two decades of advocacy. The holiday’s official website traces its history to two people who had similar ideas around the same time: Jacob Reingold and Marian McQuade. Reingold attended the first White House Conference on Aging in 1961 and shortly after instituted a Grandparents Day at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale in New York City, which soon led to a borough-wide observance. McQuade was based in West Virginia and led the effort to have that state institute a Grandparents Day in the early 1970s.

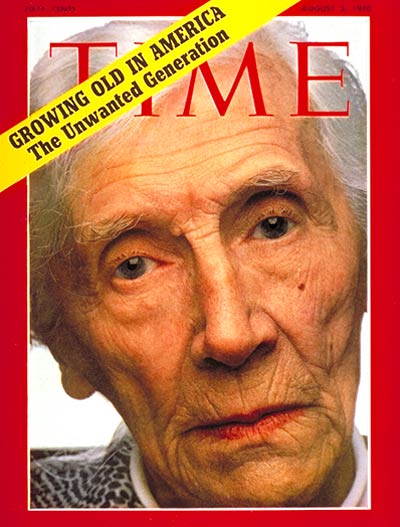

It was not a coincidence that two people in different parts of the country felt the same need to recognize grandparents. The culture of the 1960s was largely driven by younger people, and older generations, who were living longer than ever, were increasingly seen as out of touch and of diminished value. A 1970 TIME cover story about growing old in America summed up the feeling with its ominous cover line, “The Unwanted Generation.” Here’s an excerpt from the story, which was titled “The Old in the Country of the Young”:

It is as though the aged were an alien race to which the young will never belong. Indeed, there is a distinct discrimination against the old that has been called ageism. In its simplest form, says Psychiatrist Robert Butler of Washington, B.C., ageism is just “not wanting to have all these ugly old people around.” Butler believes that in 25 or 30 years, ageism will be a problem equal to racism…

It is not just cruelty and indifference that cause ageism and underscore the obsolescence of the old. It is also the nature of modern Western culture. In some societies, explains Anthropologist Margaret Mead, “the past of the adults is the future of each new generation,” and therefore is taught and respected. Thus, primitive families stay together and cherish their elders. But in the modern U.S., family units are small, the generations live apart, and social changes are so rapid that to learn about the past is considered irrelevant. In this situation, new in history, says Miss Mead, the aged are “a strangely isolated generation,” the carriers of a dying culture. Ironically, millions of these shunted-aside old people are remarkably able: medicine has kept them young at the same time that technology has made them obsolete.

Read the 1970 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: The Old in the Country of the Young

The Fun of Being a Grandson, 1955

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] On the steps of the porch, dislodging a pair of glasses ends granddad's reading period.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-01.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] In a shop, choice between glove or ball.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-02.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] On a walk, an impatient tug toward a treat.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-03.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] At the ice cream stand, something for both of them.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-04.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Six-year-old Billy Conner taking a wobbly first ride on a big bicycle as his grandfather William Conner gives him a steadying hand on the back of his seat, at home.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-05.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Six-year-old Billy Conner crying as he hugs his grandfather William Conner who pats his shoulder reassuringly in backyard at home.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-06.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![William J. Conner [& Family] An uneasy approach to the operation.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-07.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Trophy on a string.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-08.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] One puff spoils a pleasant illusion: A big act with a prop.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-09.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Billy Conner and his grandfather William climbing a tree.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-11.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] An early-morning start on a catfish expedition in a car named Old Dilsie.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-12.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Billy Conner and his grandfather William going fishing.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-13.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Billy Conner watching his grandfather William carry a puppy.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-14.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] Billy Conner talking to his grandfather William near a train.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-15.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Conner;William J. Conner [& Family] One hand free, waving at an engineer friend, the other hand holding tight.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/150902-grandparents-16.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com