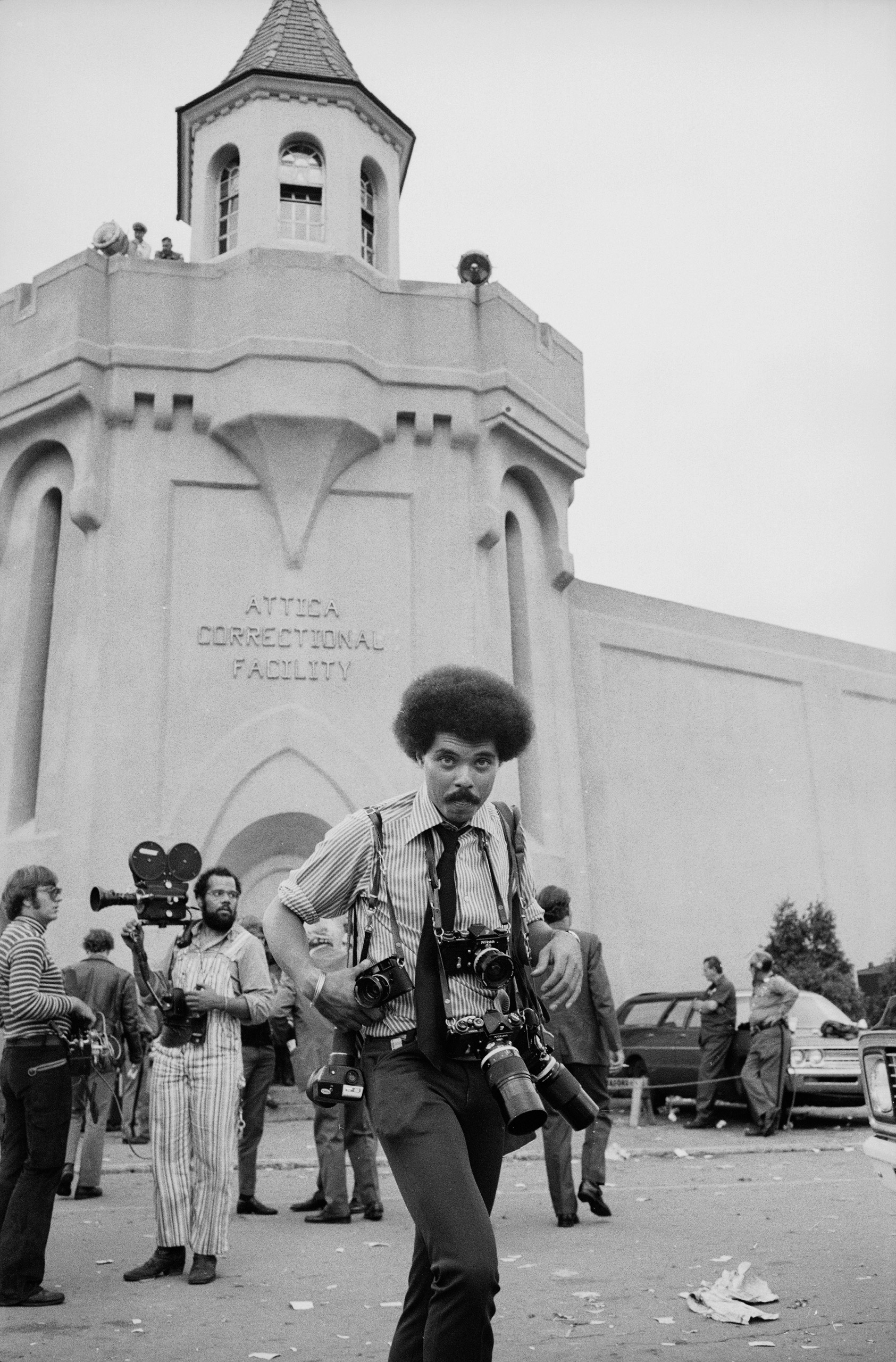

When John Shearer showed up at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York on Thursday, Sept. 9, 1971, he joined a mob of hundreds of photographers clamoring to gain entry. Rumor had it a riot was brewing, and Shearer had come with LIFE reporter Bob Stokes to capture the story. By the time they arrived, more than 1,000 inmates had taken control of the facility, with 42 officers and employees held hostage. Facing the media mob, the inmates turned away every photographer except for one: Shearer, his film in tow.

Unrest had been building within Attica’s walls for some time, as it was inside prisons across the country. Physical brutality, lack of access to medical treatment and poor sanitation were but a few bullet points on a long list of grievances. Pushed past the boiling point by the killing of Black Panther leader George Jackson at San Quentin Prison in late August, Attica’s inmates were driven to revolt that September morning, attempting to gain some ground from which to negotiate their demands. In order to release the hostages—whom they had taken in a burst of violence—they would require not only that their demands be met but that they receive amnesty for revolting in the first place.

The inmates’ decision to allow Shearer to document the standoff was anything but arbitrary. Though only in his mid-20s, Shearer had been working as a staff photographer for LOOK and LIFE magazines since he was a teenager, documenting the civil rights marches and race riots of the late 1960s. Even from inside the walls of a maximum security prison, the inmates were familiar with his work, which was—thanks to both his talent and the ubiquity of those magazines—already widely reputed. Though the riot was about prisoners’ rights on its face, racial tensions were more than just a footnote. The inmates trusted Shearer to tell the story that was about to unfold.

Looking back on it now, Shearer tells TIME that the inmates treated him well, or at least left him undisturbed to make his photographs. Even if they hadn’t, he says, “It probably wouldn’t have much mattered, because I would have tried to make pictures anyway.”

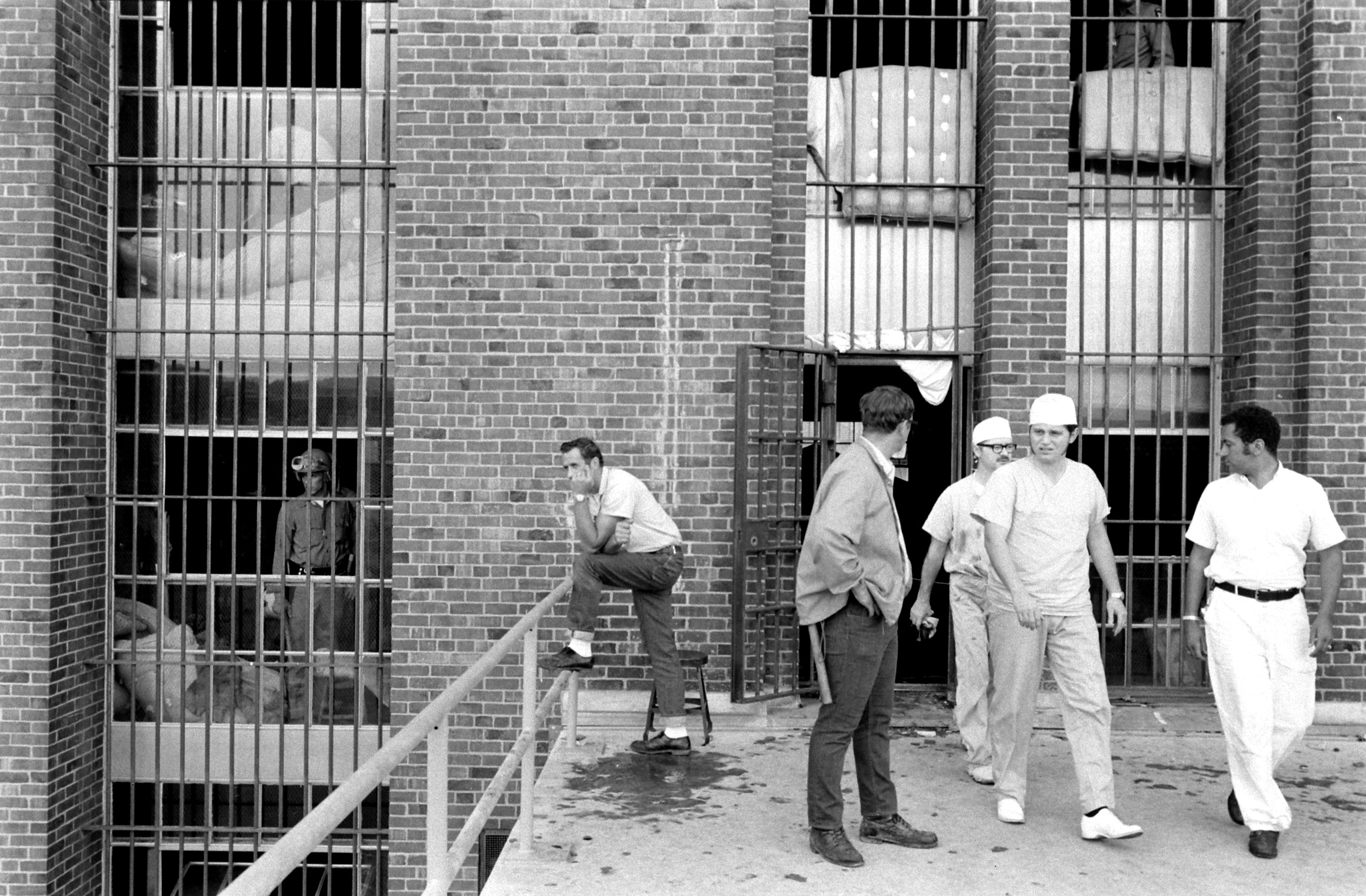

During those four days inside Attica, Shearer witnessed what would later be remembered as one of the most historic riots in the prisoner rights movement. There were the inmates, “well organized, much more than you would think,” he recalls, with designated areas for medical treatment and press communications. There was the Corrections Commissioner, Russell Oswald, whose hands were tied by orders from Governor Rockefeller. And there were the sleepless nights waiting for it all to explode in violence: “Wait, wait, wait, wait—” Shearer says, “and then it happens all at once and you have to just be ready.”

Though more violence felt inevitable, it would come only after exhaustive efforts to negotiate on both sides. Early in the negotiations, an inmate named Elliot Barkley, who would later be killed during the reclaiming of the prison by the authorities, delivered the inmates’ Manifesto of Demands, which quickly went public. But when, on Saturday, a guard died from wounds sustained in the chaos of that Thursday morning, in Shearer’s words, “the inmates’ bargaining position really just evaporated.”

Oswald, meanwhile, had come to Attica to negotiate directly with the inmates. A reformer with a philosophy rooted in rehabilitation and humanitarianism, his attempts to broker peace floundered, thanks mainly to Rockefeller’s refusal to come to the prison to quell the chaos. “Oswald was a really sympathetic guy in many ways, who was left in the lurch,” Shearer says. “He had no cards in the game to play, he was told what to do.” Shearer’s lens found the commissioner in the split second that the too-bright lights of a TV cameraman bounced off the wall and onto his downcast face. “That was taken about the time he realized what a huge mistake he made by trying to retake the prison in the way that they did.”

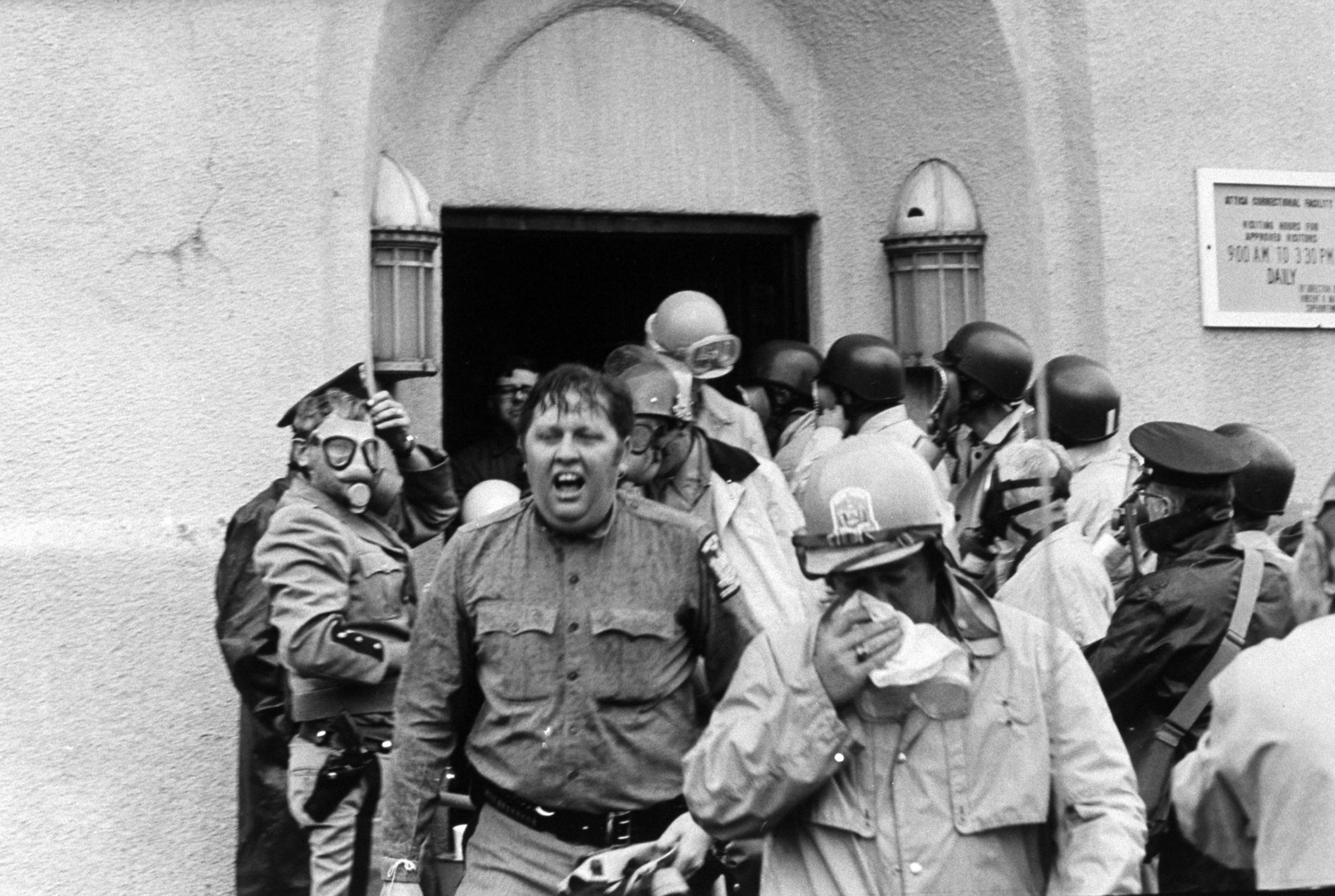

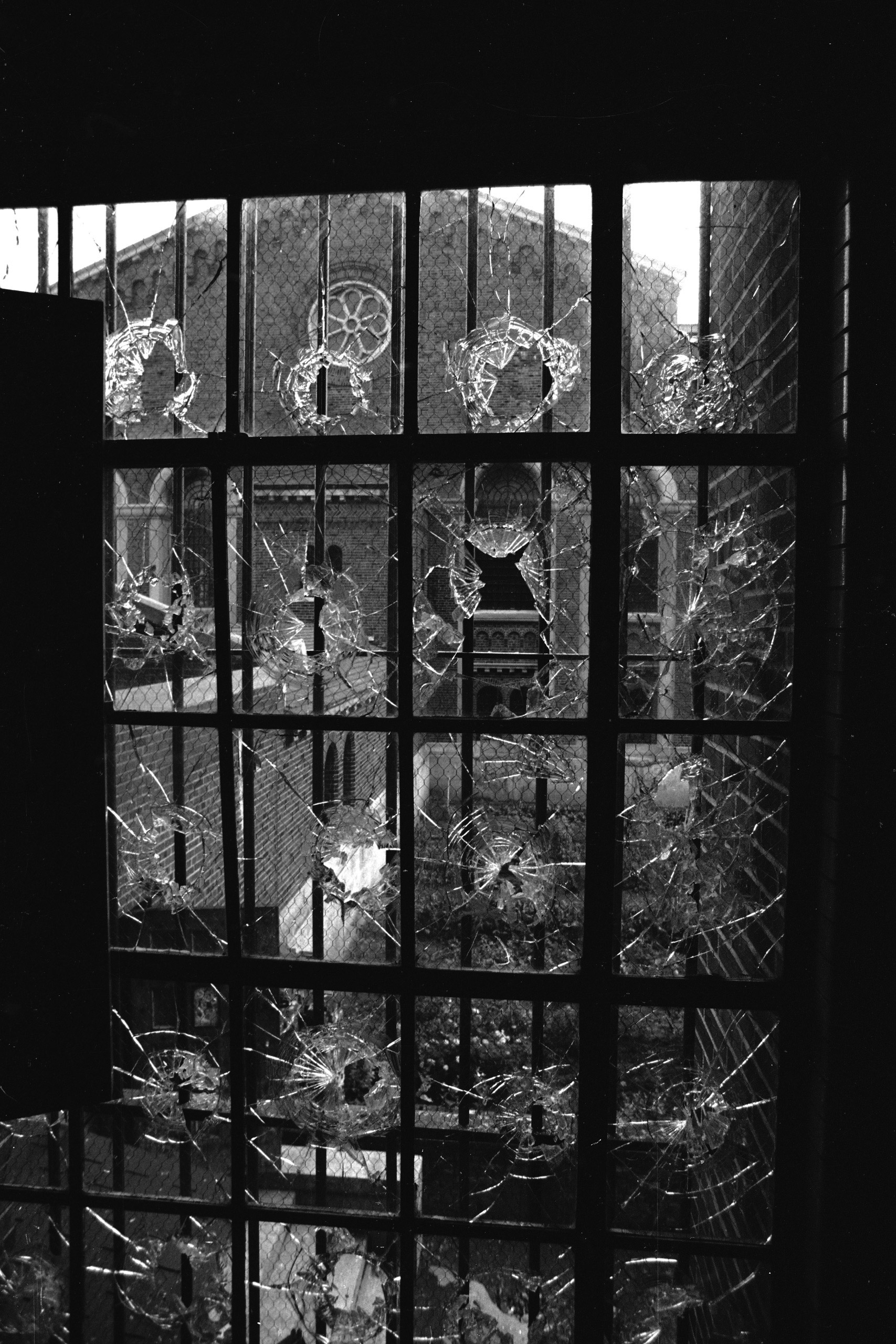

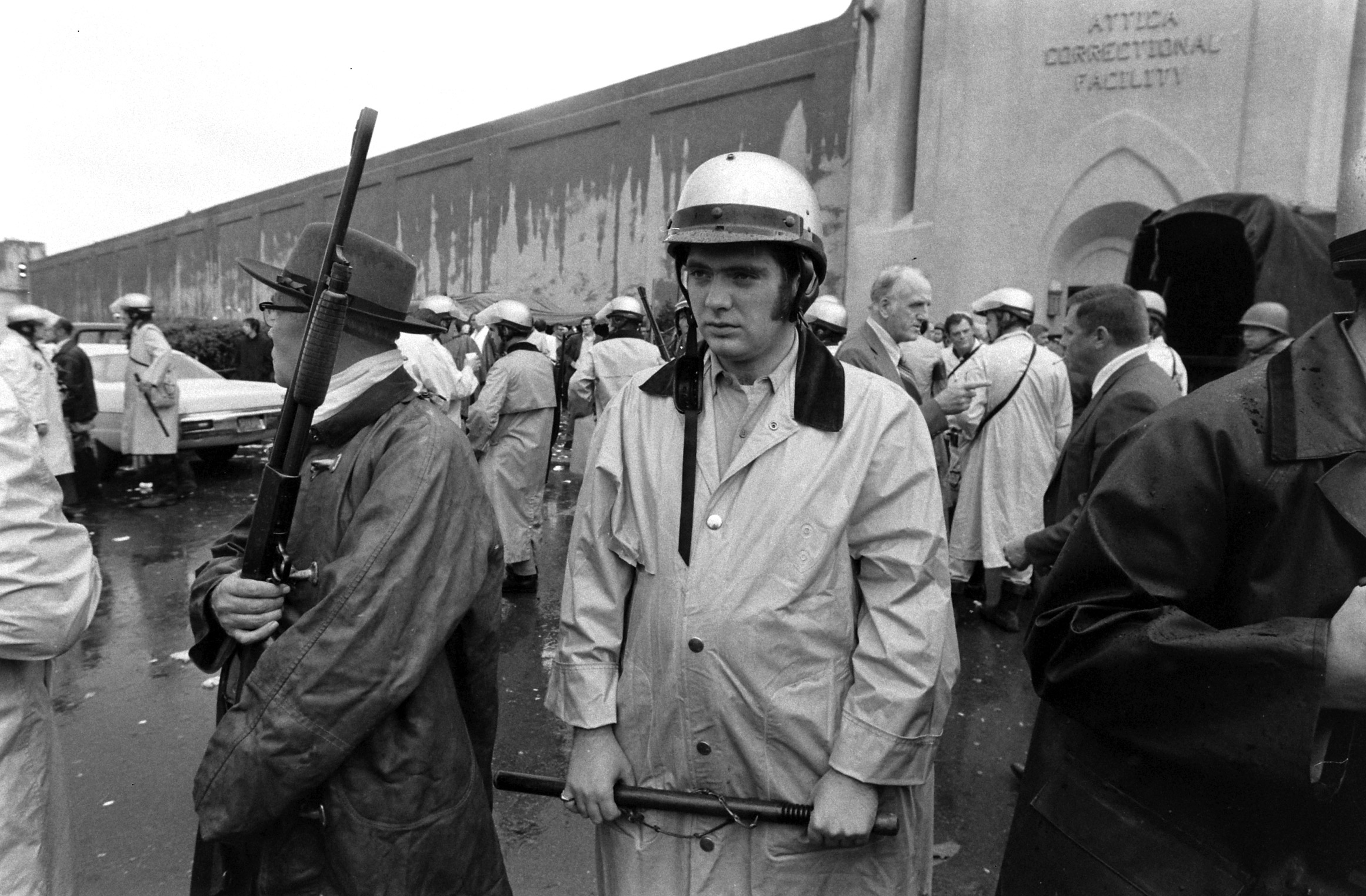

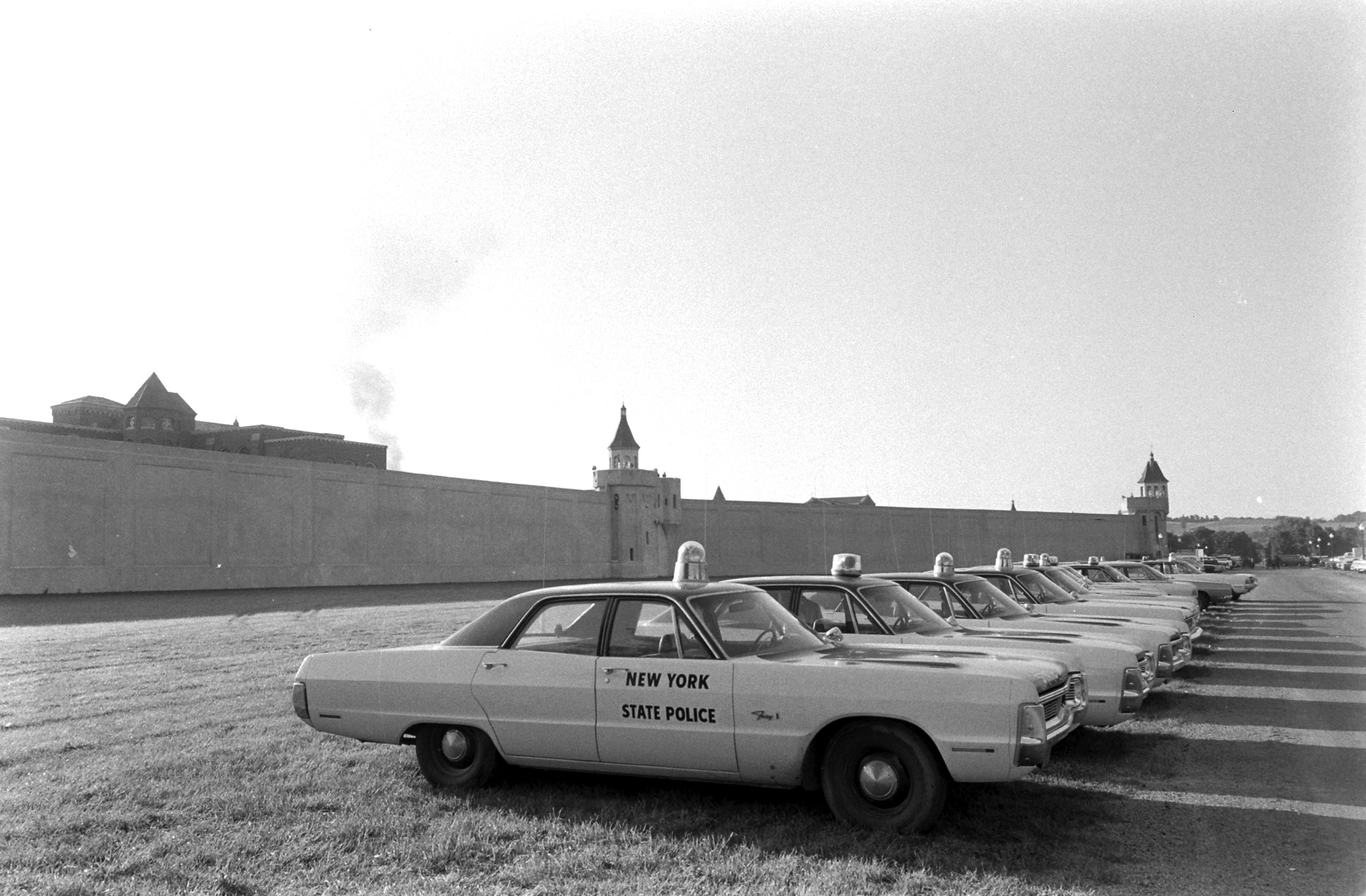

On the morning of Sept. 13, a cloud of tear gas descended upon the prison yard as the National Guard and State Police began shooting into the crowd. Laser-focused on getting the images he needed, Shearer faced a challenge: “One of the things that I had learned long before,” he explains, was that “you couldn’t really shoot with a gas mask on.” So he kept a bottle of vinegar and cotton balls in his bag, and swiftly plugged his nostrils with the vinegar-soaked cotton to maintain his vision through the tear gas.

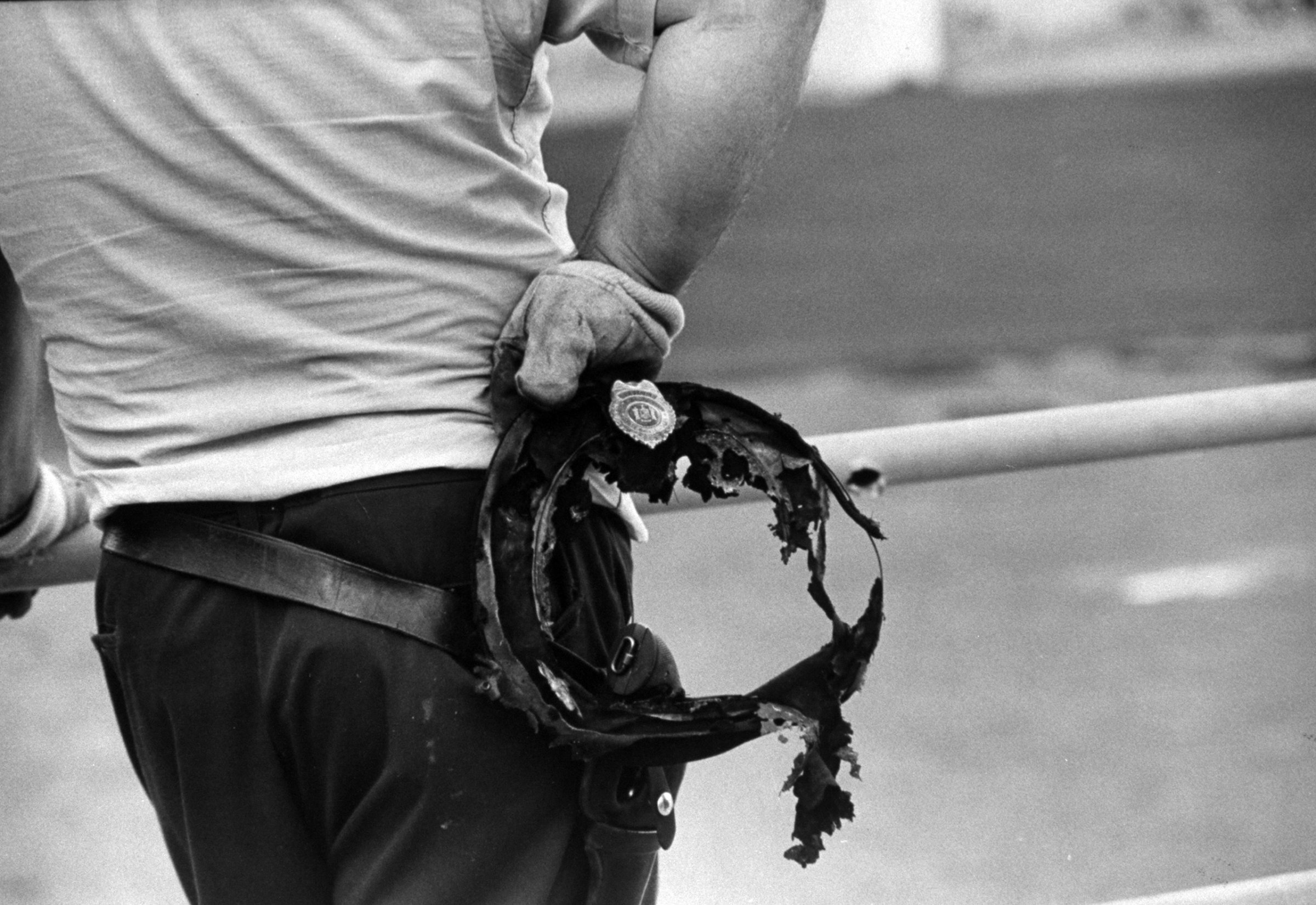

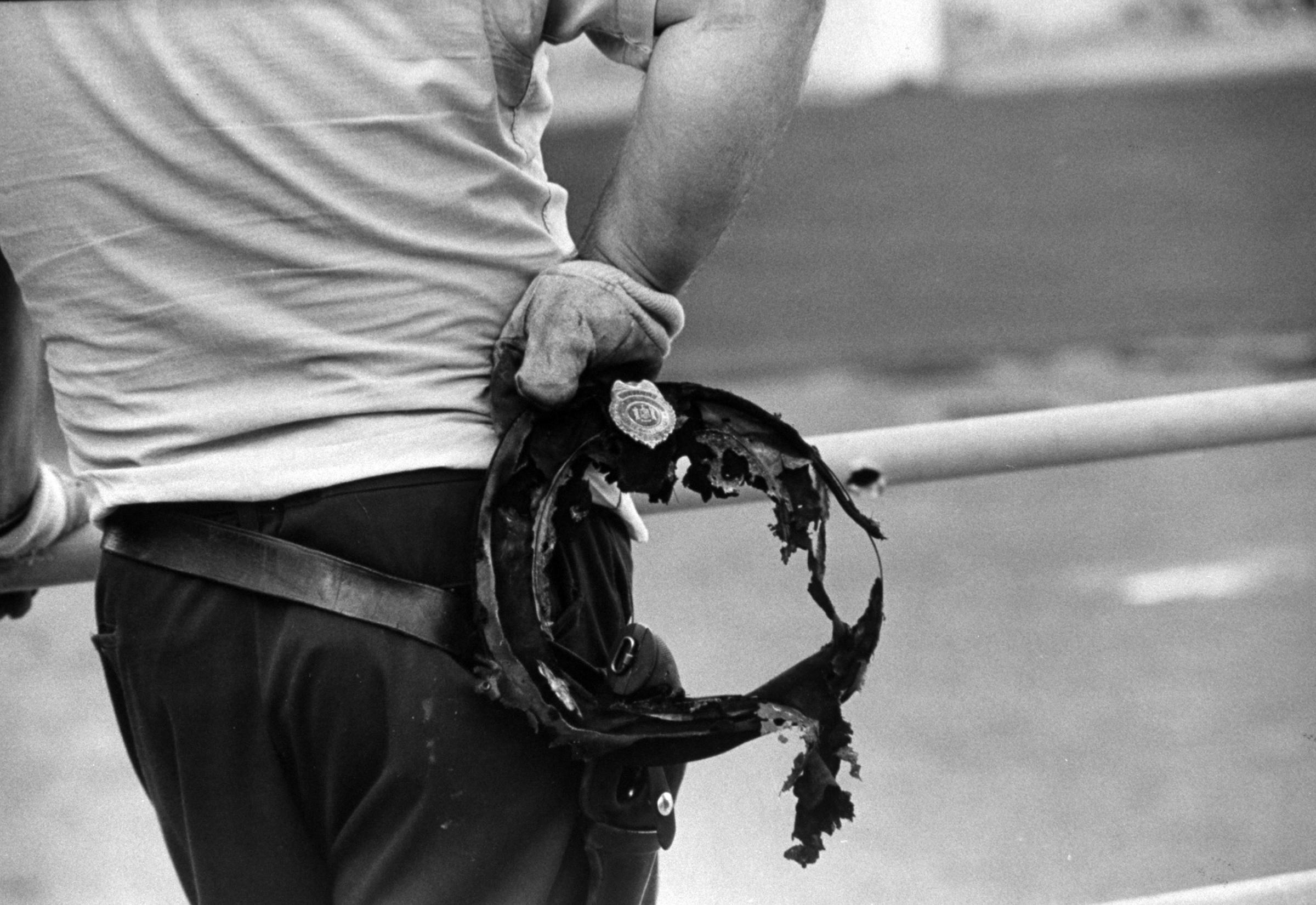

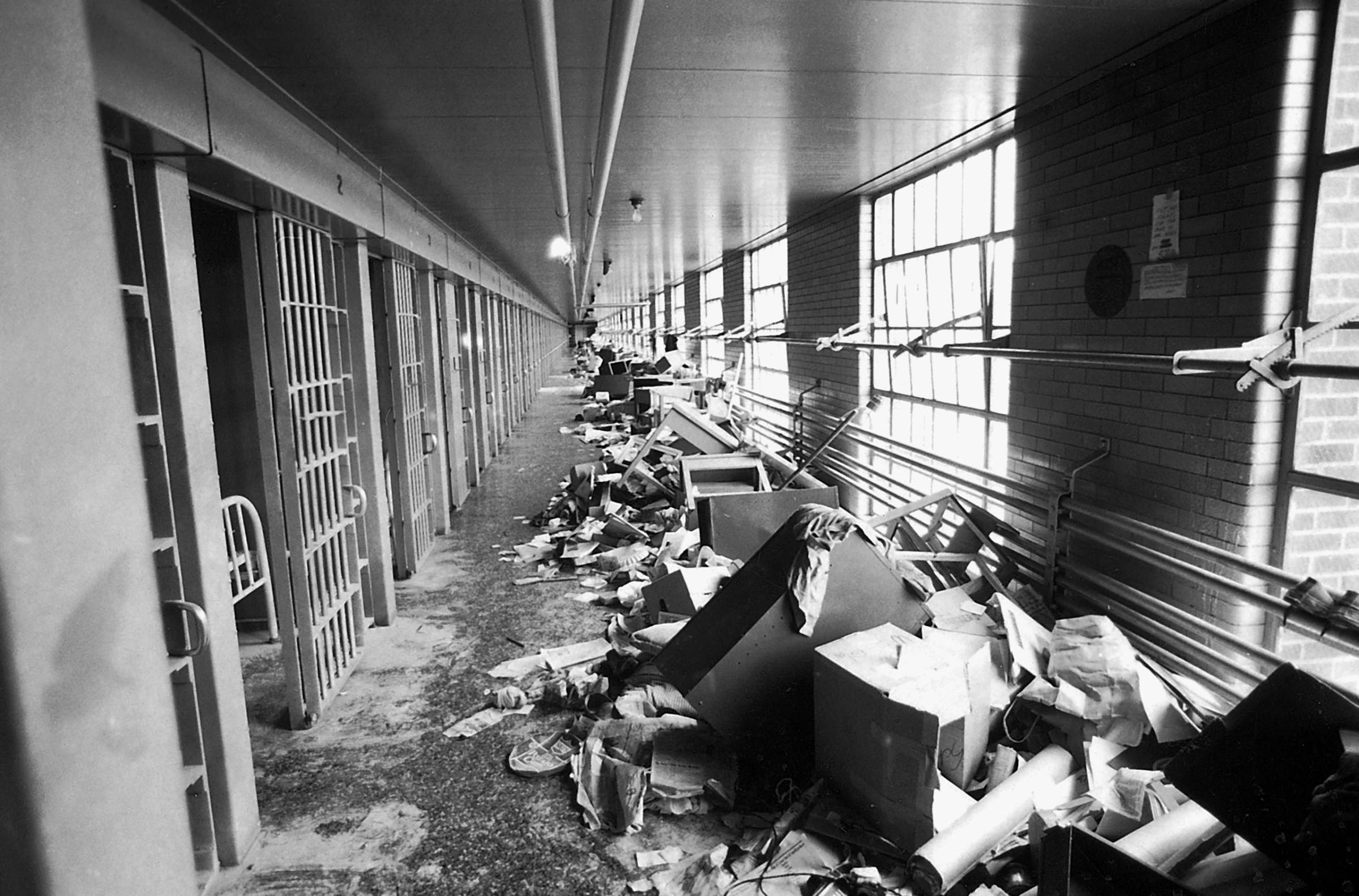

When the dust settled, 39 people were dead—29 inmates and 10 corrections employees—with more of the wounded to die in the coming days. It was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the days of the Civil War. Though rumors would circulate that inmates had killed hostages by slitting their throats, a special commission formed to investigate the incident would later deem those claims untrue, declaring: “No hostages were killed by inmates on September 13.”

Shearer himself had ample reason to fear that he might be among the day’s casualties. But danger was the last thing on his mind. “The work we did was kind of a young person’s game,” he says. “It was just about trying to come back with the pictures, and that’s the thing you thought about.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com