President Obama announced Sunday that North America’s tallest mountain, officially known as Mount McKinley for nearly a century, will henceforth be called by its Native Alaskan name of Denali. Though the announcement only makes official a name that has been used by locals for decades, it has still managed to stir up controversy as some Ohioans decry what they view as an insult to one of their most famous citizens.

But the mountain’s name is not the only aspect of its history that’s been disputed over the years.

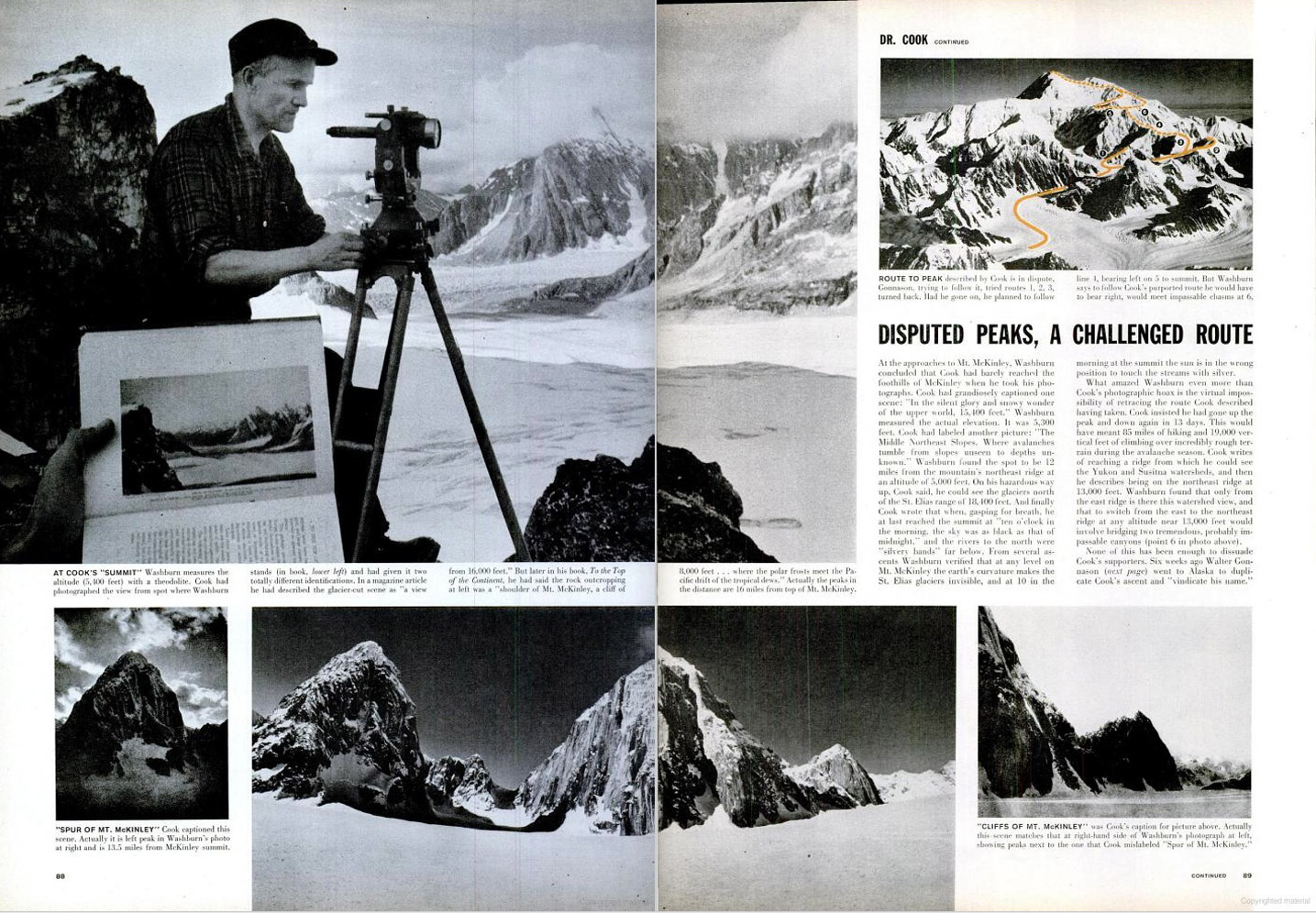

The subject of its first ascent, claimed by the explorer Frederick Cook in 1906, was the stuff of controversy for half a century — until two teams of opposing explorers journeyed to the mountain to settle the score.

Cook had set out to summit the mountain in 1906, documenting the climb with photographic evidence he hoped would prove his feat. But, soon after his return home, local Alaskan mountaineers and even Cook’s own climbing partner Edward Barrille expressed doubt that he had actually reached the peak of the more than 20,000-foot mountain. Later, when Cook’s claim to have reached the North Pole in 1909 was discredited by a Danish commission, the revelation cast an even more suspicious light on his boasts about his Alaskan exploits.

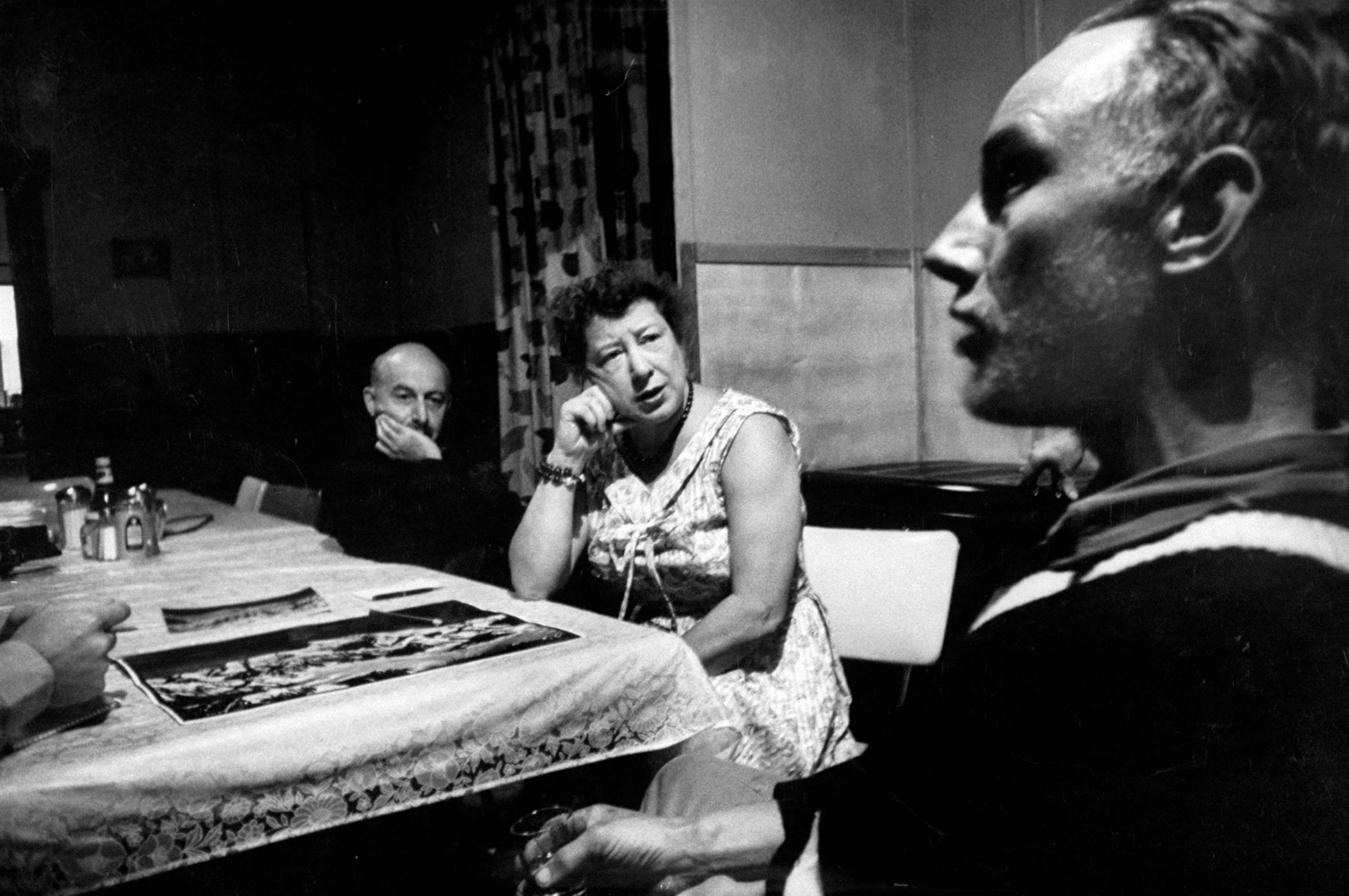

In 1956, 16 years after Cook’s death at 75, Bradford Washburn and Walter Gonnason arrived in the tiny town of Talkeetna, Alaska. The former planned to definitively disprove Cook’s assertions, while the latter intended to defend the explorer’s honor. Offering support to Gonnason was Cook’s daughter, Helen Cook Vetter, hoping desperately to remove the word “hoax” from her father’s legacy.

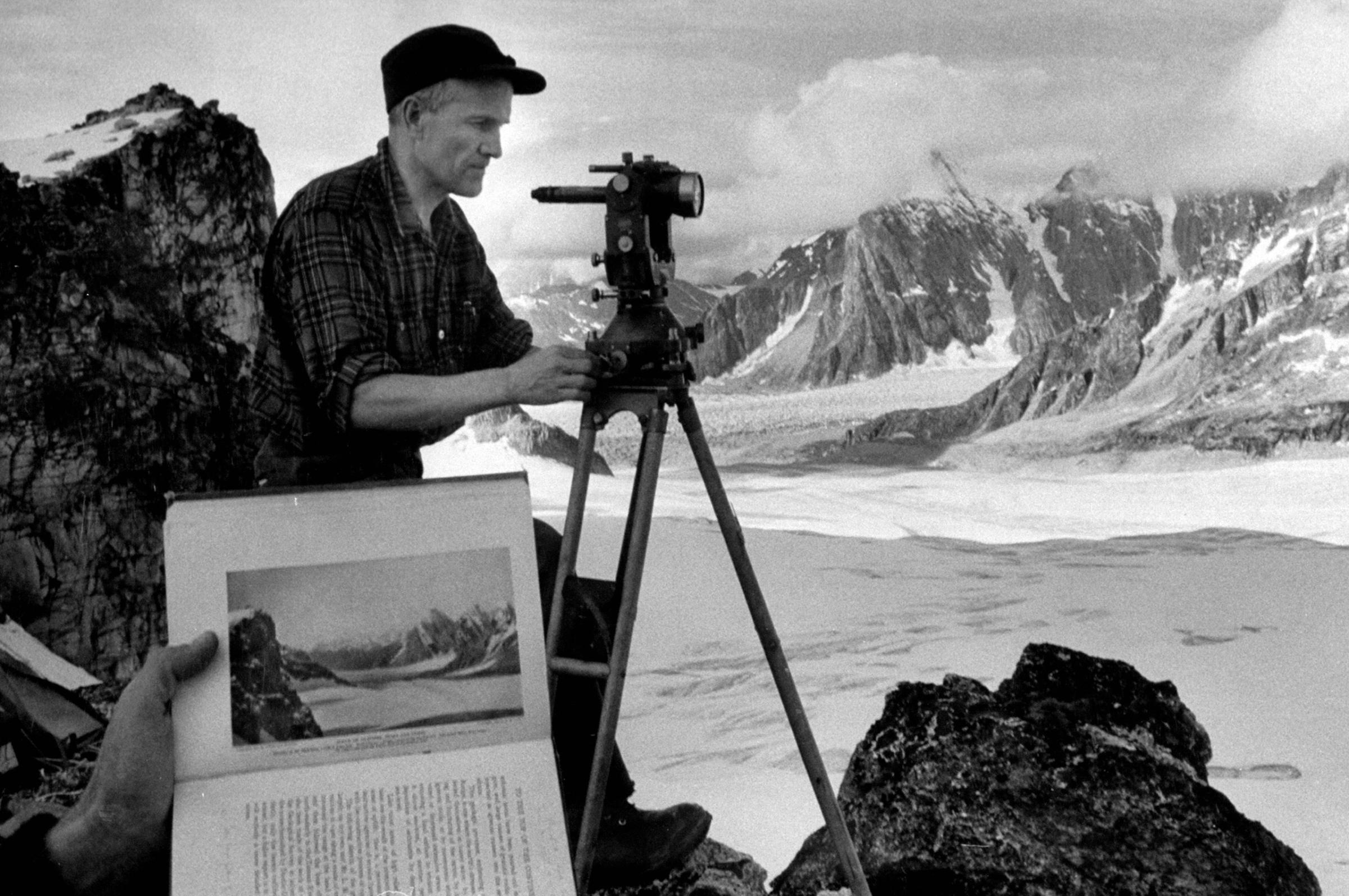

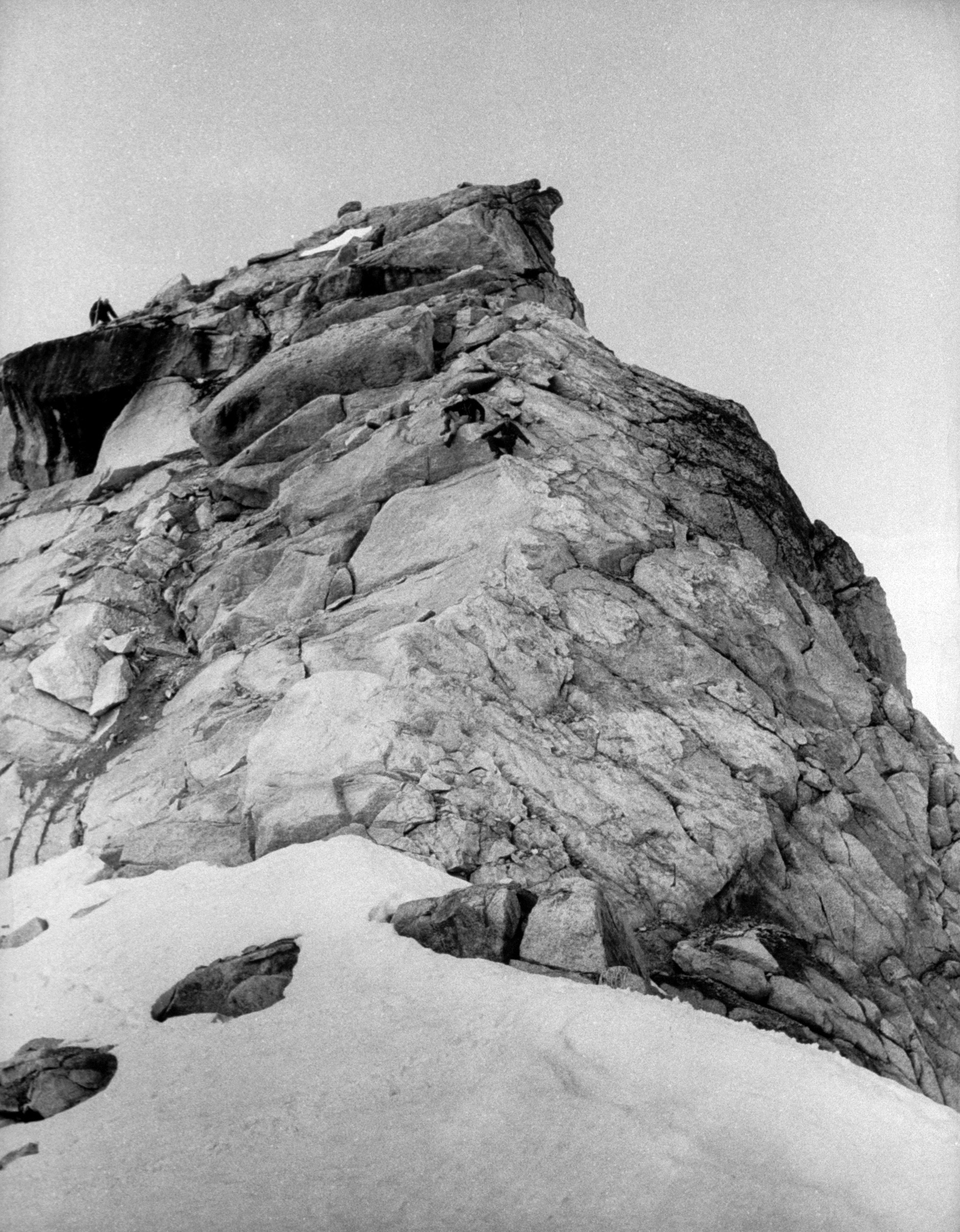

Washburn, a mountaineer and the founder of the Boston Museum of Science, set to work trying to find the locales at which Cook had taken his photographs. He quickly found inconsistencies and inaccuracies in a number of them. In one, Cook had claimed to see glaciers which, in reality, the curvature of the earth would have rendered impossible to see. As for the purported summit shot, Washburn found that it matched a small pinnacle of rock 19 miles southeast of the peak of the mountain then known as McKinley, at an altitude of just 5,400 feet.

Meanwhile, Gonnason, a mining engineer and mountain climber, attempted to recreate the ascent Cook recollected, but foul weather forced him to turn back at 11,500 feet. Though he was unable to offer proof of Cook’s ascent, he continued to maintain that disbelief in the late explorer’s accomplishments was a great injustice.

As for the first person to definitively reach the mountain’s peak, Alaska Native Walter Harper bears that honor. In June of 1913, the 20-year-old Harper was the first member of an expedition led by Hudson Stuck and Harry Karstens to complete the climb. The feat secured a place in history for Harper—no asterisk required.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

![Bradford Washburn;Helene Cook Vetter [Misc.] Mt. McKinley, Alaska 1956](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/150831-mount-mckinley-02.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Frederick Cook [Misc.];Al Stinson;Helene Cook Vetter Mt. McKinley, Alaska 1956](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/150831-mount-mckinley-05.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Frederick Cook [Misc.];Bradford Washburn [Misc.];Helene Cook Vetter Mt. McKinley, Alaska 1956](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/150831-mount-mckinley-08.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com