The first telephones were hard enough to use without the added harassment of the teenage boys who worked as the earliest switchboard operators — and who were, per PBS, notoriously rude.

It was Alexander Graham Bell himself who came up with a solution: replacing the abrupt male operators with young women who were expected to be innately polite. He hired a woman named Emma Nutt away from her job at a telegraph office, and on this day, Sept. 1, in 1878, she became the world’s first female telephone operator. (Her sister, Stella, became the second when she started work at the same place, Boston’s Edwin Holmes Telephone Dispatch Company, a few hours later.)

As an operator, Nutt pressed all the right buttons: she was patient and savvy, her voice cultured and soothing, according to the New England Historical Society. Her example became the model all telephone companies sought to emulate, and by the end of the 1880s, the job had become an exclusively female trade.

Many women embraced the professional opportunity, which seemed like a step up from factory work or domestic service. But the work wasn’t easy, and telephone companies were draconian employers, according to the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, which notes:

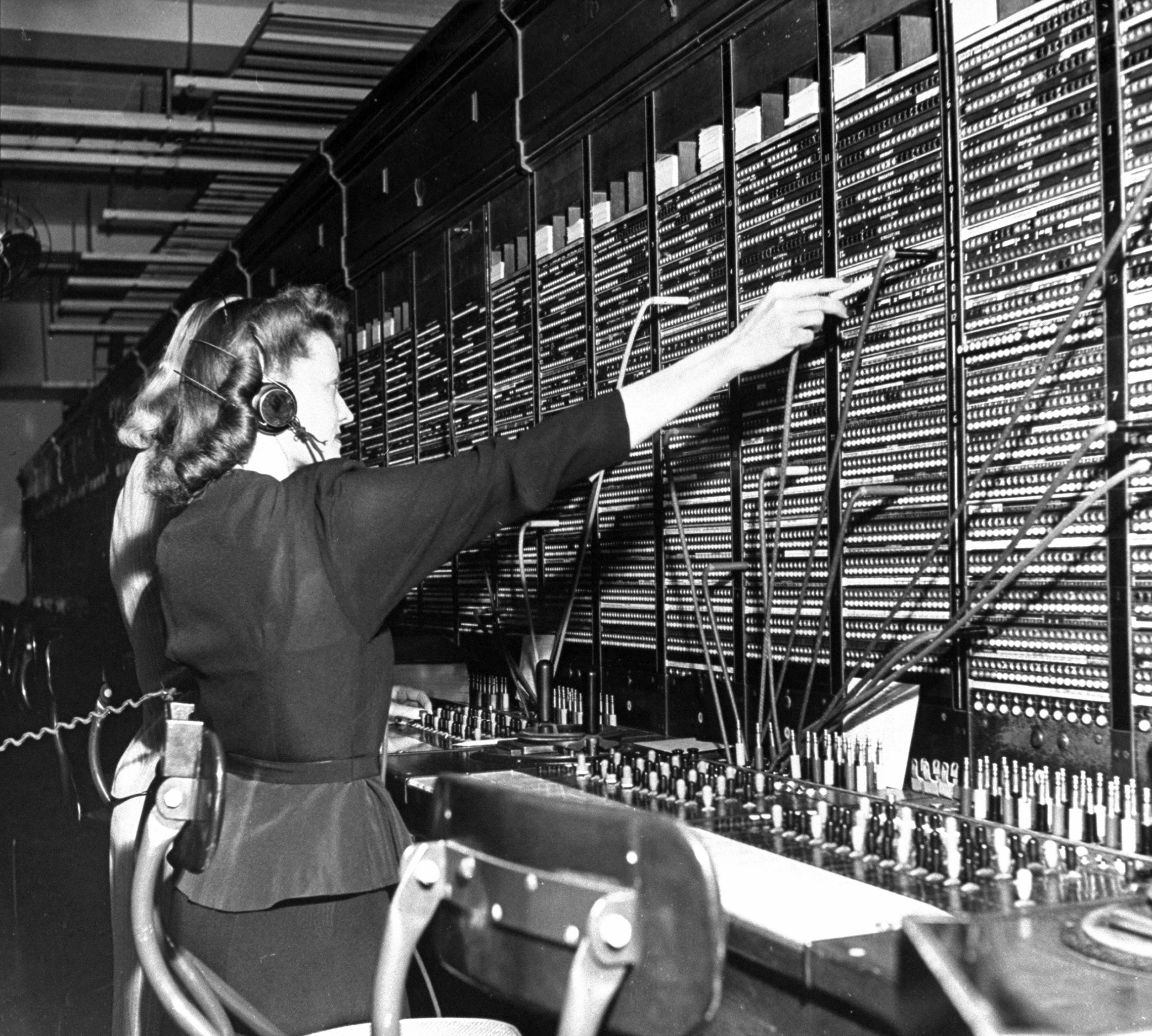

Merely to get the job, a woman had to pass height, weight, and arm length tests to ensure that she could work in the tight quarters afforded switchboard operators. Operators had to sit with perfect posture for long hours in straight-backed chairs. They were not permitted to communicate with each other. They were to respond quickly, efficiently, and patiently — even when dealing with the most irascible customers.

It soon became clear to these operators why the teenage boys who preceded them had so often talked back to their customers. One woman, in an anonymous 1922 op-ed for the New York Times, reported saying “number please” an average of 120 times per hour for eight hours a day (and sometimes at night) — and biting her tongue when she was excoriated for every possible connection problem, “including the sin of sending your party out to lunch just when you wanted to reach him.”

Working under these conditions for impossibly meager pay (Nutt herself made $10 a month working 54 hours a week) ultimately drove the women to organize. In 1919 they went on strike, paralyzing the telephone-dependent New England region — and winning a wage increase.

Nearly a century after Nutt first connected a call, switchboards remained almost entirely staffed by women. In 1973, a group of women filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission about this hiring disparity — and the corresponding dearth of women employed in other telecommunications positions. The EEOC persuaded the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (later known as AT&T) to sign an agreement opening every job in the company to both sexes.

The agreement backfired in its intended effect, however. “[It] is producing many more male operators than female linemen or telephone installers,” TIME observed later that year. Boys, it seemed, had retaken their place at the switchboard.

Read more about the 1973 case, here in the TIME archives: Crossed Wires at Bell

In Praise of the Telephone Operator

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com