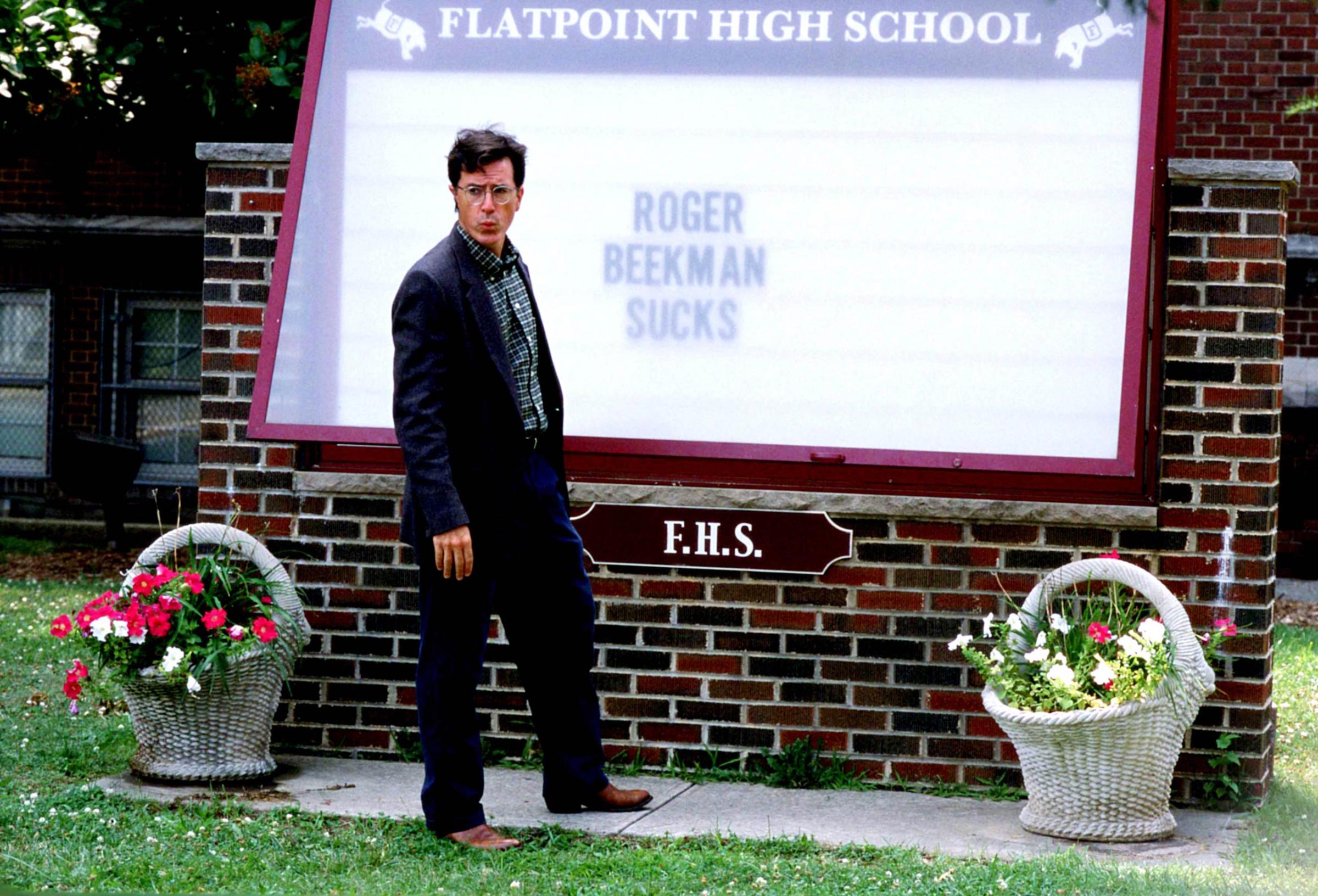

James Poniewozik’s cover story on Stephen Colbert for this week’s issue of TIME paints a portrait of a comedian in transition. Colbert, who wrapped up his tenth and final season of The Colbert Report on Comedy Central last December, has been tirelessly preparing to take the reins of The Late Show on CBS on Sept. 8.

Between meetings about set design and segments for the new show, Colbert talked about his approach to building the late night show from the ground up—not least of all introducing audiences to the man behind the character he played for so many years on Comedy Central. Below is are selections from the transcript of Poniewozik’s interviews with Colbert that didn’t make it into the final story:

How being the youngest of 11 siblings shaped him: Being the youngest of 11 children, [it was] not so much I wanted [my siblings’] attention, but I wanted to be like them. They had my complete attention as a kid, and that was a training ground for what I do because I had a big family, and there was always laughter and attention-grabbing going on. That was my training ground as much as Second City or anything else. My family happens to have an excellent view of itself. We’re big fans of us.

How having older siblings shaped his taste in culture: My music aged up. My books aged up. My interests aged up. I was a 9-year-old kid who knew what was going on in Watergate because [of] my brothers and sisters, who were getting teargased off at college. I was a music kid of the late ‘70s, but my music was—The Big Chill was no discovery for me. I had records from my brothers and sisters like an original 45 of Bill Haley and The Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” that my brother Ed bought when it came out, because he’s 18 years older than I am. Phil Silvers is like a comedic icon to me. Jimmy Durante is a comedic icon in the ways that [someone] my age absolutely should not [like].

How he got turned on to science fiction: All my allowance was spent on Mad Magazines. Then at a certain point it turned the corner and I spent it all on science fiction. My brothers Jimmy and Ed, my eldest two, had been huge science-fiction fans, so I have boxes and boxes of original 1950s and early ’60s pulp sci-fi that I read. It was so old, like you would turn the page and they would snap off. I still have most of them with rubber bands around them to hold them together, like old copies of Stranger in a Strange Land or Mutant by Henry Kuttner or C.M. Kornbluth, really old like nobody reads that stuff anymore.

How he got into comedy and why he didn’t pursue standup: I wanted to be an actor and discovered improvisation in Chicago through a friend who [invited me] to go see this thing called The Herald Improv. I saw it and I was immediately like, I want to do this. That was performance, scene work, ensemble, character. I’ve done things that are like standup since then. There’s a quality to any of the shows that has a standup component to it, and I admire standups, but I actually like playing with people. I find being onstage with just me and my jokes, the mic and audience is a lonely business. I don’t think I could have lived on the road like that.

Why he was ready to say goodbye to The Colbert Report: I still enjoyed it, but to model behavior, you have to consume that behavior on a regular basis. It became very hard to watch punditry of any kind, of whatever political stripe. I wouldn’t want anybody to mistake my comedy for engagement in punditry itself. And to change that expectation from an audience, or to change that need for me to be steeped in cable news and punditry, I had to actually leave. I had to change.

Toward the end of the last show, it was an act of discipline for me to continue to do the character. The discipline was not even just keeping the character’s point of view in mind or his agenda or a bible of his views, but there was also a need to not let people in, not let people see back stage—not necessarily know who I am so that the character can be the strongest suggestion in their mind when I do the show. If I let them know too much about me or our process, then I would be picking the character’s chicken. I don’t want to put so much light behind that particular stained glass or else he would fade completely.

Why it’s incorrect to think he never broke character in The Colbert Report: We would edit any mistake I ever did. People said, “Oh, you never broke” or “You rarely broke.” That’s because we always took it out, because part of the character was he wasn’t a f—up. He was absolutely always on point. Win. Get over. Stay sharp. That was his attitude all the time, and we had to reflect that in the production of the show. None of that is necessary anymore. Now I can be a comedian.

Whether his new show will resemble his old show in any way: You have to be willing to do everything you know how to do. Carson said it to Jay, who said it to Conan, who said it to me. These shows require everything you know how to do. So the idea that there are things that we did over there that we wouldn’t do at the new space, I think, is an unrealistic approach to the need. And whether it fits is a discovery to be made, not a philosophical exercise to engage in before you do it. It’s athletic, not intellectual.

What he did during his time off: My daughter is in college but I’ve got two boys at home. I helped my son go buy wood for his Eagle Scout project. Pick up the kids from school. Hang out with my wife. Go see some family. Went for an open ocean race, sailed.

What it’s been like preparing to take over The Late Show: Yogi Berra said this great thing—or he didn’t—which I love, but I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, which is, “In theory there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.” That’s what this is like. This is like, in theory what we’re doing with all these cards on the wall is really getting us ready to do the show in the fall. In practice, only doing the show in the fall gets you ready to do the show in the fall. So why am I doing all of these things? I don’t know, other than that’s what I do for a living, and if I don’t do it I feel like I’m not doing my job. I’m not learning anything if I don’t do it.

Why he hosted a public access TV show in Monroe, Mich. in July: I was like, I don’t want to do the first show on the first night that’s terrible. And one of my writers goes, “Why don’t we just go to a cable access station and do a show?” So we did a lot of research and then were like, we like that show. Let’s do Only in Monroe, and everything on the show has to be about Monroe. Monroe was nice. It’s a pretty little town. Had a great burger at Larson’s Bar. Though there were a lot of people in Monroe [who] thought we chose the wrong bar.

What it was like producing a show in a local TV station: Everybody at the station was just great. I mean, it was a state of the art station from 1999. We ran it live at midnight that night. We fed it out of a laptop over their system, practically with a rubber tube, to get it over their system. Their ratings are normally 12 people. I’m not joking. That’s not a joke. Twelve is their average rating for that show. And so there were 12 of us in the studio when we were feeding it out, and after it was over, I checked Twitter. No one had seen it. No one had said anything.

How he’s planning to introduce his audience to the real Stephen Colbert: We’ve got a series of field pieces, packages that are ways for me to try to figure out who that is, as if I don’t know who I am. The unexamined life can be extremely enjoyable, and who knows if I do know who I am. We’re going to see whether I do. I’ll have my own suppositions as to what these answers might be from people and see if their memory of me is the same or whether the police investigator we hired to investigate me finds out. We’re doing a series called “Who Am Me?”

Who he’s most excited to talk to for “Who Am Me?”: My elementary school teacher, my favorite teacher from elementary school, is just so excited. I had such a crush on her. I’m going to talk to her. I haven’t seen her since 1974 but I can’t believe that they found her. She moved away when I was 10 and then she came back just recently, so they found her down in Charleston.

How he approached set design for The Late Show: The number one thing about a theater is where is your focus: am I performing for the room that the camera is capturing, or am I performing for a camera that the room gets to see? That’s the question. I have an instinct as to which one of those it is, but I won’t know until I do it. How many play spaces will I have? Do I just want one? How do I adjust to the fact that I have a live band there every night, which is something I haven’t had before? How adaptable do I want this space to be, digitally? Do I want physical objects? How am I going to play with the fact that I have a balcony? How does it affect me that I go from three cameras to six cameras? All those sort of things that are kind of boring to talk about, but as the guy who sits at the desk and all this is around him, I care about all of it.

The set can’t be the star, but it still has to be very attractive. In some ways, we want the set to look like look that great new apartment Stephen got—I know why he took that show, I’d love to live there. It’s like we’re inviting you into my new pad without denying the existence of the theater. That’s the challenge: Can you create a set that lives within the reality that you’re in a theater but still has the intimacy? The show is extremely intimate, so you want a guide. How do you maintain that intimacy while acknowledging you’re in a Broadway theater at the same time?

What his plans are for the opening credits to the new show: I can’t tell you anything that’s going to be visual, but I can tell you that it was important to me that the city itself, New York, is part of the character of these shows, the energy of being in the city. We’re trying to capture some of the energy, the energy of a day of New York in the opening credits. And that’s what it’s about. It’s all over New York. We’re shooting all over the city.

How he thinks about what he will cover on the show: You have to basically sift through what you like and what you don’t like about performing, or what you really enjoy about your relationship with an audience. I have to give myself the patience to literally use my imagination and go—when I close my eyes—what would I enjoy seeing as a consumer? I don’t mean that as like market testing consumer, I’m literally a fan of comedy. What do I want to see on TV?

What he admired most about David Letterman: His disregard for status and respectability. That’s it. It reminded me of Mad Magazine that way. I love it. Those wrestling shoes he used to wear. That’s it. That’s the disregard for status, those wrestling shoes.

Whether David Letterman offered any advice before Colbert took the reins: We had a very lovely evening. He met me in his offices. He had a bottle of water and he answered questions. He was very nice about it. He just answered questions for about an hour and a half for me, and it was two guys with similar jobs talking shop. It was entirely pleasant, and he was very gracious to me. At the end of the night he showed me how to run the freight elevator and that was it…it was like being handed the keys to a car and someone just saying, “Let me show you how to use the clutch—it sticks.” It was beautiful.

Why he’s grateful that he was settled in life before getting this job: I feel very lucky that I got this kind of gig as old as I was. I was 41 before anybody stopped me on the street, so I hope I had a sense of who I was. I was married; I had all my kids; I had my house; my little suburban lifestyle with my Volvo and my khakis going to the dry cleaners on a Saturday. That’s me. I’m boring—not boring—I’m common. I don’t mean that pejoratively. I’m very common. I happen to have this job that very few people have but I’m very happy that I like khakis and an oxford cloth shirt. I like being boring to a certain extent. I don’t have to be flashy. I get to put all of that into a show and when it’s over I don’t have to be that.

How he knows whether a joke will work: After a while I don’t actually need to hear the audience to hear the audience. I know kind of what the rhythm is, theoretically, on a maybe 75 percent successful scale—like what might be a joke that would fit in a scene or a sketch or a monologue. But not having an audience is agonizing. I miss the audience so much. That’s the hardest part about right now, not being in front of anybody.

How his relationship to the audience has evolved: I learned from a director early on who said you got to learn to love the bomb, and that meant learning not just to feel like you’re going to get through it, but that you actually kind of like that you’re getting nothing from the audience. That took me a long time. It took many, many years for that to be okay. Then you’re really aware of your relationship with the audience. You’re not constantly asking. That’s a tough thing to do with an audience—go out there and constantly go, “Love me, love me, love me.” It’s much better to be perceiving their needs and giving, giving, giving to them. And then they’ll give you something genuine back.

See 13 Stephen Colbert Cameos You Might Have Missed

Read next: Five Things You Learn in TIME’s Cover Story on Stephen Colbert

Download TIME’s mobile app for iOS to have your world explained wherever you go

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com