Is the current cornrow controversy much hairdo about nothing? Or a gateway crime against black culture that includes stealing everything from music to art to clothes to language? Cornrows are just the tip of the follicle, but because so many white celebrities have adopted this hairstyle, it has become the public platform to discuss the broader topic of cultural appropriation. Celebrities who have exhibited cornrows include Fergie, Gwen Stefani, Heidi Klum, Paris Hilton, Justin Timberlake, Jared Leto, David Beckman, and, more recently, Lena Dunham, Kendall Jenner, Kylie Jenner, and Kim Kardashian. Several of them have taken heat for popping the cornrow, and prompted some African-Americans to accuse the dominant white American culture of stealing cherished icons of identity from the subjugated black culture. Kind of like wearing the teeth of your pillaged enemy as a necklace.

Most white Americans would agree that the influence of black culture on America is significant. Without the black swing, blues, and jazz musicians, there is no Elvis or Jerry Lee Lewis or rock ‘n’ roll. And the influence is evident in all aspects of American culture, from fashion to food, from language to literature. What most white Americans won’t agree with is that there is anything wrong with that. In fact, they would argue that such assimilation of ethnic influences has occurred with every immigrant group in America, whether Latino or Irish or Vietnamese. They would argue that it is a symbol of American inclusion that we so readily embrace these foreign influences into our culture. The melting pot and so forth. American culture is not appropriating anything—that would be stealing!—it’s honoring black culture through homage. America acknowledges the influence and gives the influencers full credit. And, after all, isn’t weaving black culture into mainstream American culture the best way to end racism? Are cornrows the ambassador to racial equality or just another version of Al Jolson mammying in blackface?

One very legitimate point is economic. In general, when blacks create something that is later adopted by white culture, white people tend to make a lot more money from it. Certainly, one can see why that’s both annoying and disheartening. Through everything from access to loans to education, systemic racism has created a smoother path to economic success for whites who exploit what blacks have created. It feels an awful lot like slavery to have others profit from your efforts.

Loving burritos doesn’t make someone less racist against Latinos. Lusting after Bo Derek in 10 doesn’t make anyone appreciate black culture more. So, the argument that appropriation is the same as assimilation doesn’t hold up. Appreciating an individual item from a culture doesn’t translate into accepting the whole people. While high-priced cornrows on a white celebrity on the red carper at the Oscars is chic, those same cornrows on the little black girl in Watts, Los Angeles, are a symbol of her ghetto lifestyle. A white person looking black gets a fashion spread in a glossy magazine; a black person wearing the same thing gets pulled over by the police. One can understand the frustration.

Another aspect that infuriates many African-Americans: what white culture deems worthy to borrow is often so narrow that it perpetuates negative stereotypes rather than increases racial appreciation. Underwear sticking out of pants? Hip-hop language? Twerking? An unintended byproduct is that white people, feeling aglow in One-Worldness brought on by taking a hip-hop exercise class, forget the serious state of racial inequality that still exists and needs to be constantly addressed. In the face of being shamed and persecuted, African-Americans have cultivated art and fashion to maintain pride in who they are, so to see other cultures take this and profit from it while still allowing the shame and persecution to persist makes us want to holler.

Having said all that, here’s the harsh reality. Whether we call it cultural appropriation, assimilation, exploitation, homage, plundering or honoring, it will continue to happen unabated or affected by complaints and protests. Sure, some products, like ones featuring the Confederate flag, can’t seriously claim to be an homage, so public outcry is more effective in eliminating them. But for the most part, Culture is a ravenous beast that consists of many commercial outlets that need to sell consumer goods. Music, movies, clothes, books, art, etc., are the products that keep the beast alive, but they have to evolve in order to do so. Because of that, all non-mainstream cultures are subject to being looted for inspiration to create new goods to sell.

It is some consolation that, on a smaller scale, African-Americans have been able to do some cultural appropriation of their own. Once upon a time, professional sports were all white. Today, more than 77% of NBA players and 67.3% in the NFL are black. From 1950 to 2009, 81 percent of Billboard’s Top 10 bestselling albums were from non-white or mixed-race groups of artists. This shift will continue over the coming decades. The Census Bureau estimates that by 2060, 56% of the population will belong to racial and ethnic minorities—a minority majority. With each subsequent generation, cultural icons truly will be based on assimilation, not appropriation.

“Almost cut my hair,” Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young sang in 1970 about a long-haired boy suffering from an identity crisis. Cutting his hair would be to turn his back on the cultural revolution happening at the time in order to seek comfort in rejoining the social norms he doesn’t believe in. In the end, he doesn’t cut his hair because, “I feel like I owe it to someone.” It’s just hair, it grows. But, like cornrows, it is symbolic of a cultural identity that does not want to be homogenized—like Pat Boone’s 1956 sleepy version of Little Richard’s dynamic “Tutti Frutti.” Wop bop a loo bop a lop ba ba, indeed!

Read next: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: White People Gets It Right About Being White

Download TIME’s mobile app for iOS to have your world explained wherever you go

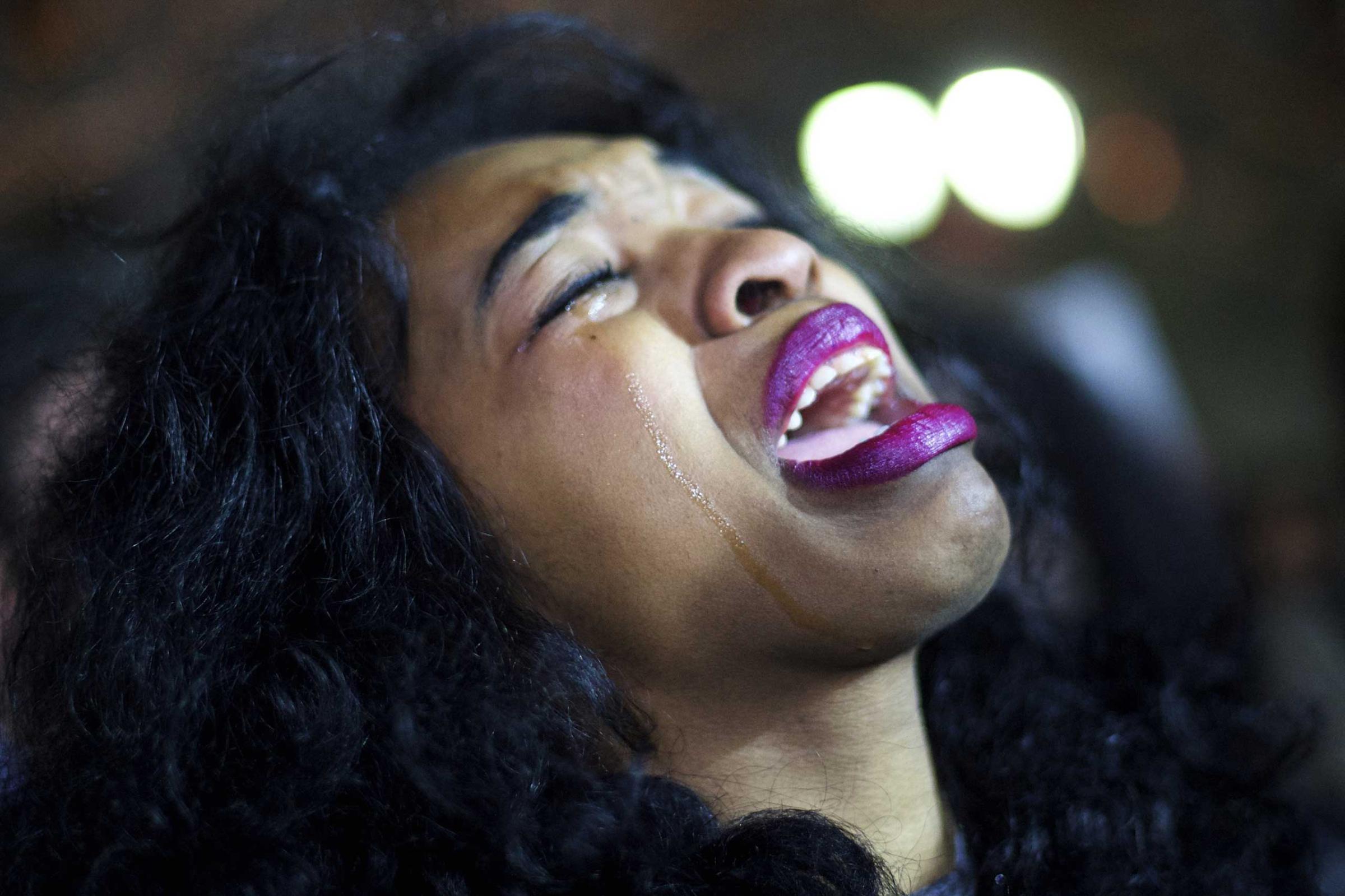

Witness Protesters Taking Over the Streets After the Eric Garner Grand Jury Decision

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com