Every year, YouTube creator Devin Graham makes his own version of a summer blockbuster: a live-action recreation of the high-flying parkour jumps in the video game series Assassin’s Creed. The elaborate short films regularly garner tens of millions of views for Graham’s production company, Devin Super Tramp, and can cost upwards of $50,000 each to produce.

This year’s version, set in London and published in July, has only received 2.5 million views on YouTube to date. But that’s not because people have suddenly grown tired of watching acrobats perform heart-stopping leaps across buildings. It’s because many people are seeing Graham’s videos on Facebook first, where they’re often posted without his consent. That’s a big problem for Graham, because unlike the official YouTube clips, the unlicensed Facebook uploads don’t put any money in his pocket.

“It does dramatically affect us as filmmakers, people doing what they love to do and as a full-on film production company,” says Graham.

This practice, which online video creators are calling “freebooting,” is taking off on Facebook, helping spur the site’s massive video growth. The social network is now attracting more than 4 billion video views per day, up from just one billion in September. It’s unclear how many of these views are coming from copyright-infringing content, but a recent study by ad agency Ogilvy and video analytics firm Tubular Labs found that about 72.5% of the top 1,000 Facebook videos in May were re-uploaded from other sources, an easy task with freely-available software.

Online video creators, who make money by selling advertising against their content, are increasingly frustrated with the problem. In June, George Strompolos, CEO of the multichannel network Fullscreen, said on Twitter that pirated versions of Fullscreen creators’ videos were racking up more than 50 million views on Facebook. This month, Hank Green, longtime YouTube vlogger and co-founder of the online video conference VidCon, penned a diatribe against Facebook’s video policies, arguing that the social network’s preference for Facebook-native videos in its News Feed algorithm encourages theft of creators’ YouTube videos.

“It’s a little inexcusable that Facebook, a company with a market cap of $260 BILLION [sic], launched their video platform with no system to protect independent rights holders,” Green wrote.

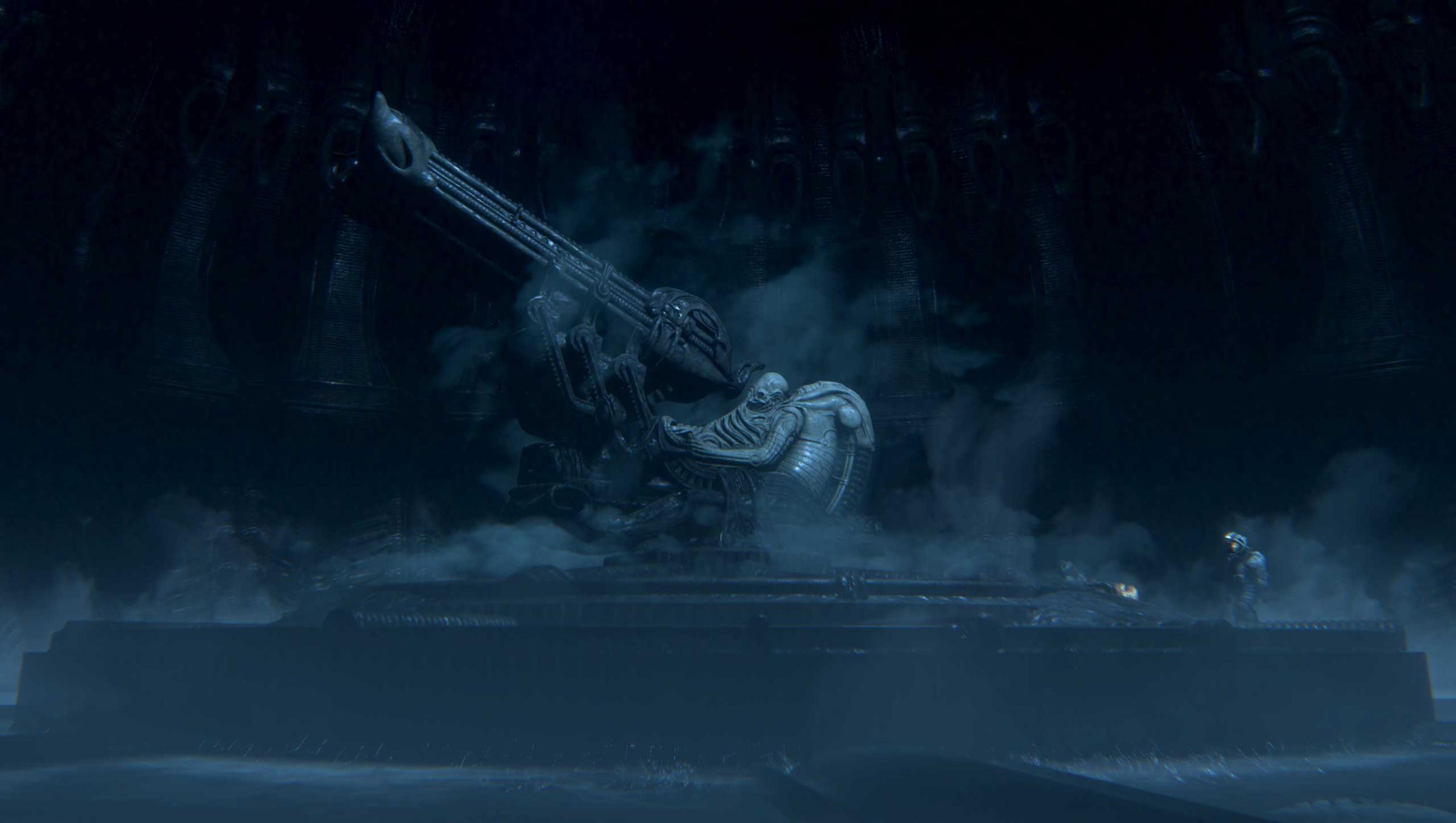

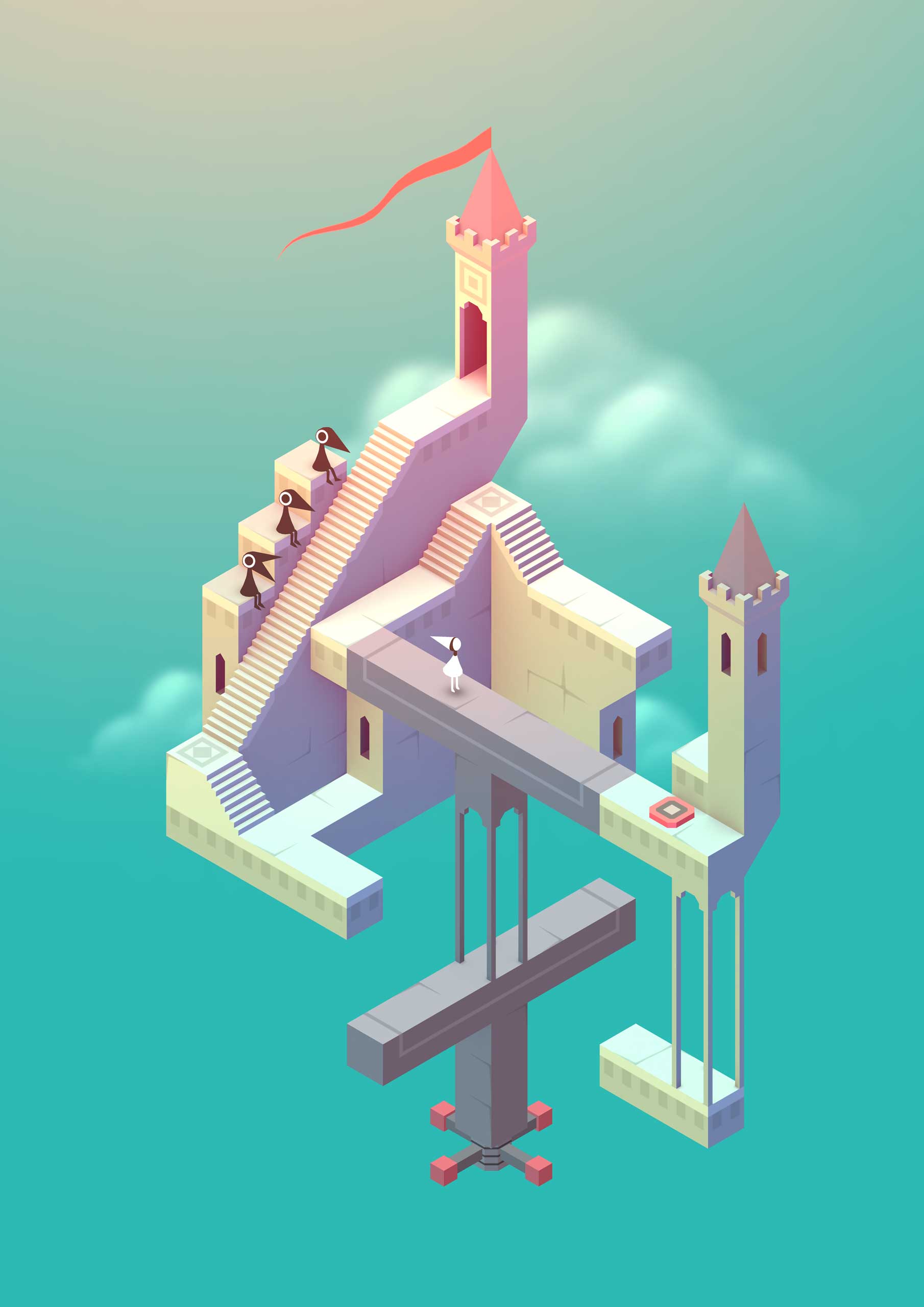

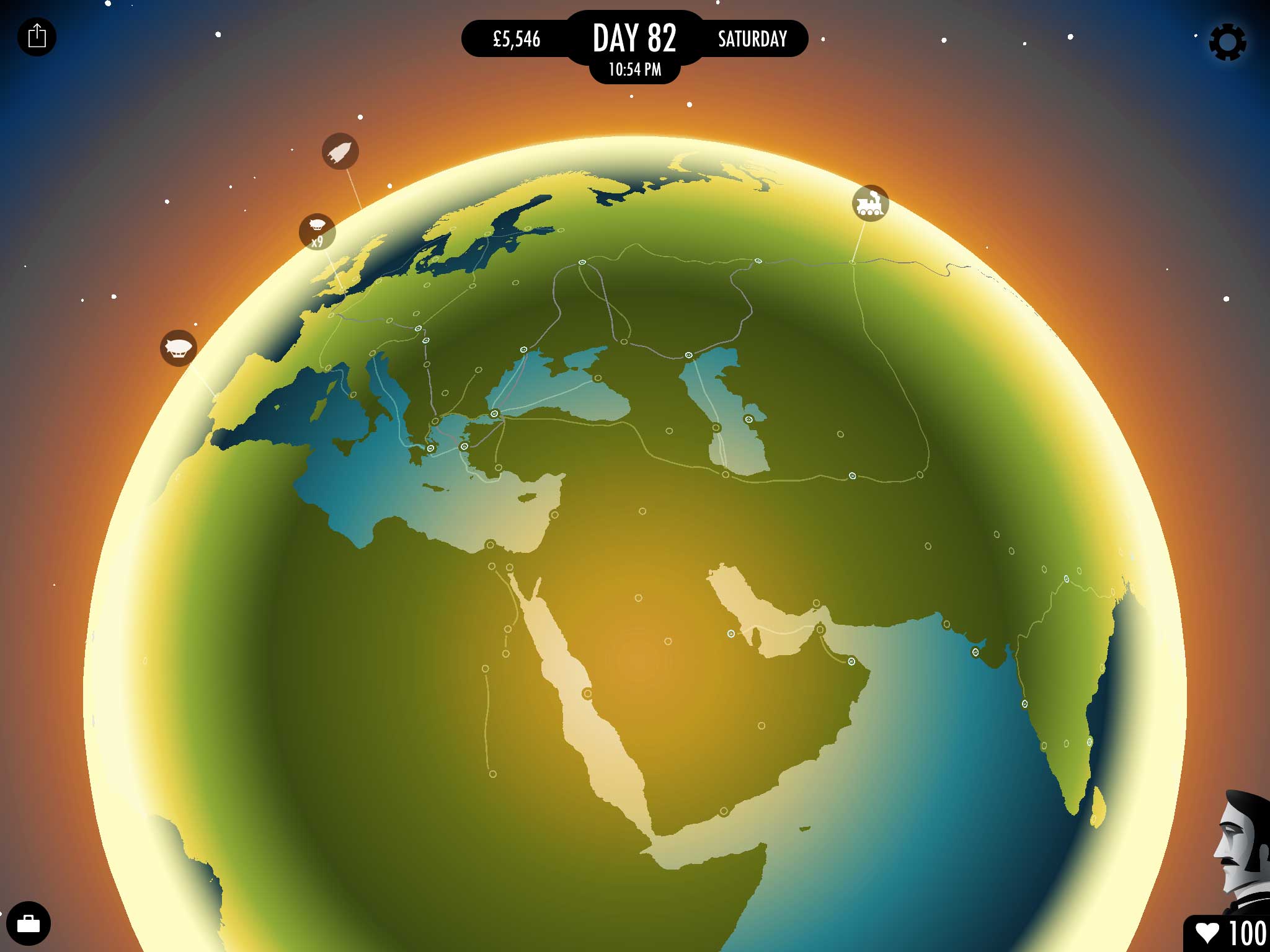

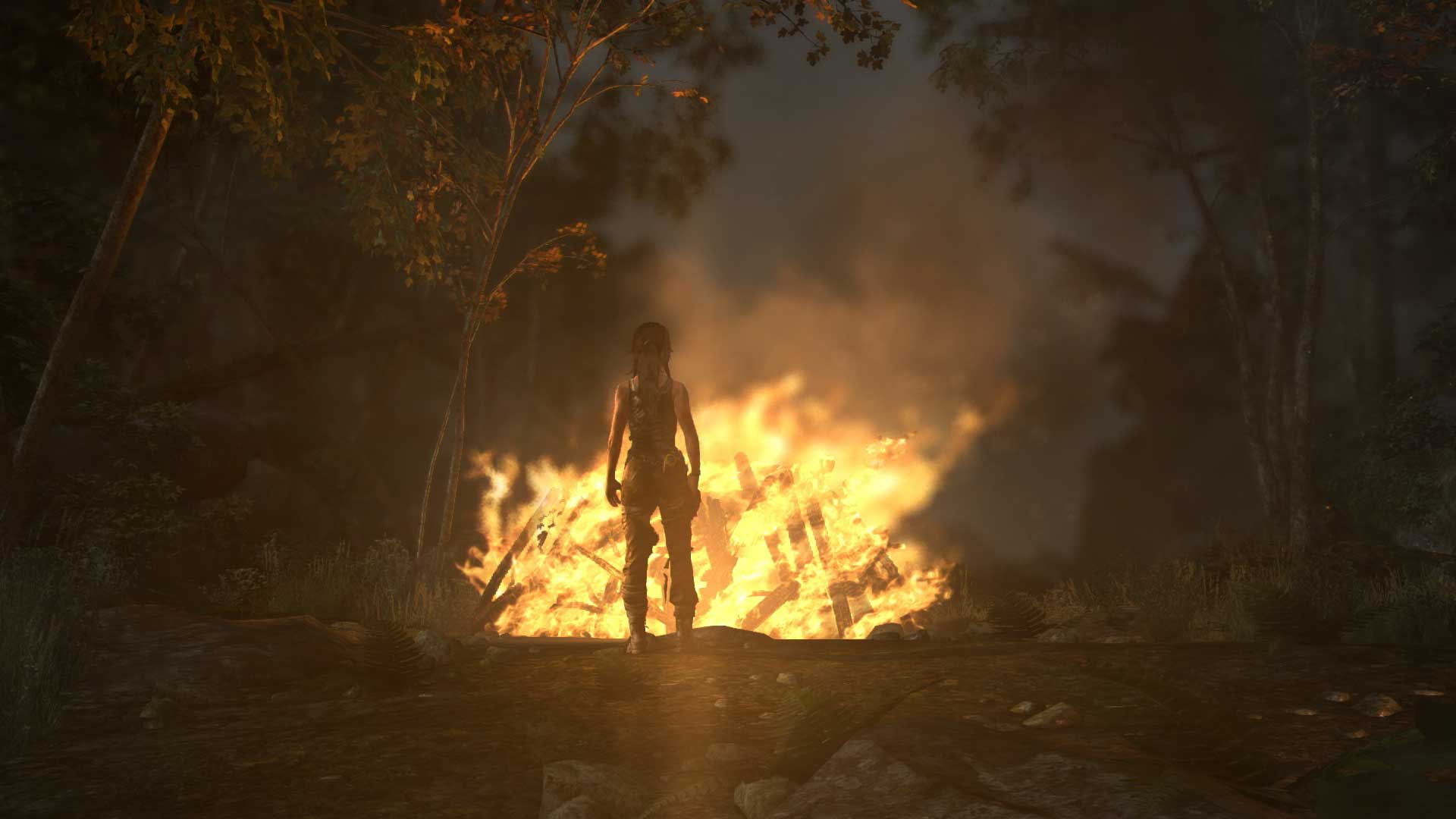

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

YouTube itself faced similar issues in its earliest days, with users easily able to upload and search for pirated versions of television shows to the site for free. Viacom sued YouTube for more than $1 billion in 2007 for copyright infringement, shorty after the video site had been bought by Google. The case was eventually settled out of court, but it helped spur YouTube to create Content ID, a copyright-flagging system that lets rights holders either remove unlicensed copies of their content or monetize those unauthorized videos by selling ads against them. YouTube has made more than $1 billion in payments to more than 8,000 rights holders using the Content ID system so far.

Green and other YouTube creators are now calling on Facebook to create a similar copyright-flagging system. It’s been the online video natives adept at making viral content who have been most hurt by freebooting, as Facebook Page owners lift videos of adorable animals, extreme sports and other highly-shareable content to boost their own social media audiences. Collectively, these creators helped YouTube generate an estimated $5.6 billion in advertising revenue in 2013, and the biggest stars now rake in millions of dollars per year. But they still lack the clout of the traditional media giants who initially compelled YouTube to clean up its act.

“Facebook pages aren’t stealing content that advertisers would even think of as copyrighted because it’s not made by legacy media,” Green told TIME in an interview. “That’s part of why this has been such an easy thing for Facebook to get away with for so long. It doesn’t feel like copyrighted content. But it is, and it’s a big deal for the creators who do this professionally and have their content being stolen every day and getting tens of millions of views.”

In an emailed statement, a Facebook spokesperson said the company uses a system called Audible Magic to identify copyright-infringing videos. The social network also has a system whereby users can flag individual freebooted videos, though by the time a video has been removed it has often already garnered millions of views. Users who make repeated IP violations may also see their accounts suspended. Facebook also says it’s working on new features “to help [intellectual property] owners identify and manage potential infringing content.” Details could be announced later this summer.

The pressure to create a more comprehensive system is likely to increase as Facebook courts more video creators and begins sharing ad revenue with them. In July the social network announced that it’s launching a revenue-sharing program with select video partners including the NBA, Funny or Die and Hearst. “Media companies don’t create content to have it ripped by somebody else and not receive their rightful share of revenue or data from that,” says Rich Raddon, co-founder of the digital media rights management company ZEFR.

For now, creators are simply waiting for a better solution to arrive as they continue to depend on their fans to help them spot unlicensed copies of their videos. “All of a sudden we’re competing against our own video for views,” says Graham. “It’s a real struggle.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com