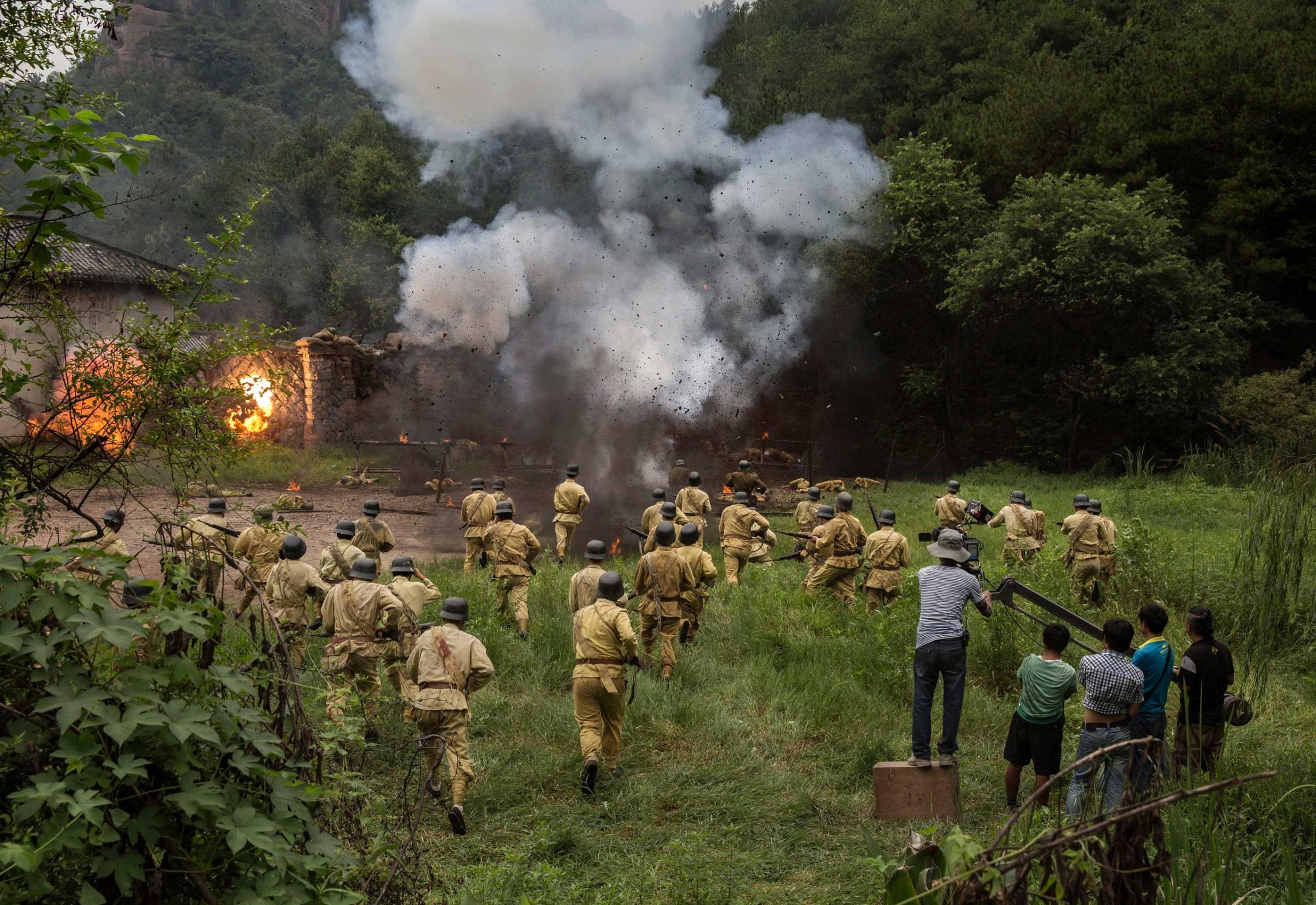

A bomb blasts shrapnel across the faces of wounded men; Chinese soldiers run victorious toward the front line; a hostage lies on the ground with a noose around his neck. While these scenes often play out on a large screen before thousands of viewers over handfuls of popcorn, the lesser-known scenes are the ones in between: makeup artists touch up fake war wounds; film crews bark orders; a bloody soldier yawns before the camera rolls — these moments, captured by Getty Images photographer Kevin Frayer, convey a fierce Chinese patriotism.

The six productions are part of hundreds of war-themed films, documentaries and performances releasing this month in celebration of the Second World War’s 70th anniversary. While the holiday gives sway to China’s World War II moviedom, the trend is not new. “You spend a day in this country and chances are you’ve seen one of these on a television set in a hotel room, somebody’s living room, in the window of a shop or while you’re eating noodles in a restaurant,” Frayer says.

The films, which depict Chinese communist-led forces as self-glorified victors over the oppressive enemy, have been recently labeled by International Business Times as propaganda. Following the invasion of Japan during the 1930s, China was subject to harsh colonial rule. Seven decades later, Japan’s purported refusal to acknowledge its imperial past has led to strained relations between the neighboring countries.

For Frayer, the movies are not as much anti-Japanese as they are nationalistic. “I don’t think these films glamorize war any more than the ones we make in Western countries, marking our wartime victories over the Germans or the Japanese in the Second World War,” he says. “It’s a substantial part of their history, so they are marking the 70th anniversary just like everybody else.”

Frayer’s photos portray a certain human element rarely seen on screen: a cameraman reacts in elation to a successful action scene; an extra smokes a cigarette on props after an outtake. “You see these Chinese actors come from outer cities to get blown up on screen and die as Japanese soldiers for the equivalent of 10 U.S. dollars a day,” Frayer says. “And then in between takes, they are sitting there on their smartphones like everyone else.”

Filmed at Hengdian World Studios in eastern China, Frayer captures the over-the-top pyrotechnic stunts and special effects of these high-end productions, which are put on by some of Asia’s top professionals in the film industry. Beyond entertainment value, the photos also show how these wartime stories are vehicles for a look at normal life and romance, and can even have historical value.

Frayer has been covering Chinese culture for more than two years. Earlier this year, he won the Getty Images and Chris Hondros Fund Award, which comes with a $20,000 grant to support his documentary work.

Kevin Frayer is a freelance photographer represented by Getty Images.

Mikko Takkunen, who edited this photo essay, is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @photojournalism.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter @rachelllowry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com