Smartphones, light fixtures and cheap shoes aren’t the only thing made in China. The next global recession might be, too.

This week’s international market rout, triggered by the biggest fall in Shanghai markets since 2007, has brought nearly every asset class down with it—European markets, U.S. stocks, global commodities, emerging market bonds, and so on. The U.S. has clawed back some early losses on August 24 already, but investors are jittery that the plunge in the Chinese market portends some larger sea change in global markets. Many are wondering if the world is entering a period like the Asian financial crisis of 1997 or even, God forbid, the worldwide slowdown of 2008.

I don’t think either are likely, but here’s what the global market crash is telling us:

1. The global debt crisis of 2008 hasn’t gone away—it’s just moved to China. Lots of analysts like to talk about how much “deleveraging” has been done by Western consumers and companies since the financial crisis. That’s true, but debt, like energy, doesn’t disappear—it just takes on new forms. When American consumers stopped buying stuff after the subprime crisis, China tried to take up the slack in the form of a massive government stimulus program. This meant a major run up in debt: A few years back, it took a dollar of debt to create every dollar of growth in China. Now it takes four times that. The debt-to-GDP ratio in China is a nauseating 300%. (American debt hawks worry about our rate, which is less than a third of that.)

A couple of years ago, that bubble started to burst. The Chinese government tried to stop it, by propping up one market after another, from housing to stocks. But now, having spent $400 billion to buoy overpriced stock markets in the last few weeks, they’ve realized they have to give in to gravity and let the markets fall. That fall is an acknowledgement that the government can’t micro-manage the Chinese economy forever. But investors don’t trust that China is going to be able to move smoothly from a state-run economy to a consumption led one (whatever Tim Cook might say about Apple phone sales in the Middle Kingdom). It’s a shift that only three countries in Asia have ever made—Japan, South Korea, and Singapore.

2. A slowdown in China is now a much bigger deal than it used to be. During the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, U.S. growth powered ahead. But the size of the Chinese economy has grown wildly since then. China made up about a third of all global growth over the last decade, even more than the US (which made up 17%). “This represents a major break from the past,” as Morgan Stanley’s chief macroeconomist Ruchir Sharma has pointed out. “Historically, the U.S. has been the single largest contributor to global growth, and a contraction in the American economy has been the catalyst that tipped the world into recession.” Now, it may be China that has that dubious role. While government statistics still say China is growing at 7%, Sharma puts that figure closer to 5%—which may not be enough to stave off a global recession.

3. This isn’t a disaster for the US, but it’s not good. U.S. companies aren’t as exposed to China as many emerging market countries. But U.S. companies do get a third of their earnings internationally now, about twice the rate in the 1990s. A fall in Shanghai isn’t going to tank our markets a la 2008 or push the U.S. itself back into recession, assuming that our own recovery continues at the current pace. But it will mean that we stay basically where we are, hovering somewhere between 2% and 3% growth, with stagnant wages, and not enough steam to turn the current recovery into something more robust. The downturn in China will add to the deflationary effects already at play in the economy, which will make it harder for employers to give raises, and tough to imagine much stronger growth in a U.S. economy made up 70% of consumer spending. That could make it hard for the Fed to hike interest rates in September (which would, in turn, draw out the already large and worrisome corporate debt bubble that has grown to record highs fueled by low-interest rates).

4. The world is still awaiting a true fix to the financial crisis of 2008. China isn’t the only place debt flowed after companies and consumers offloaded it following the subprime crisis. Governments around the world are holding more debt than ever before thanks to their efforts to buoy things post 2008. That means they are out of ammo to bolster the global economy with more fiscal stimulus, or, in the case of the U.S., with more central bank money dumps. Meanwhile, as interest rates rise, the corporate margin debt and share buybacks that have been fueling the market buzz will end, too. “The market hasn’t experienced even a 10% correction since late 2011,” says Sharma. “So, it was vulnerable to some bad news.” The solution now isn’t more easy money, but to create real growth, the old-fashioned way—with big infrastructure projects, more support for the innovative new businesses that create most of the jobs in the country, and so on. Tough stuff, and not something that will happen quickly.

The takeaway: the debt and central bank fueled market boom of the last few years is officially coming to an end. Keep your money in U.S. blue chips and T-bills (they are still the safest thing going). But be prepared for much more volatility, which is already much higher this year than last. And don’t expect anywhere near the kinds of portfolio gains you saw over the last couple of years.

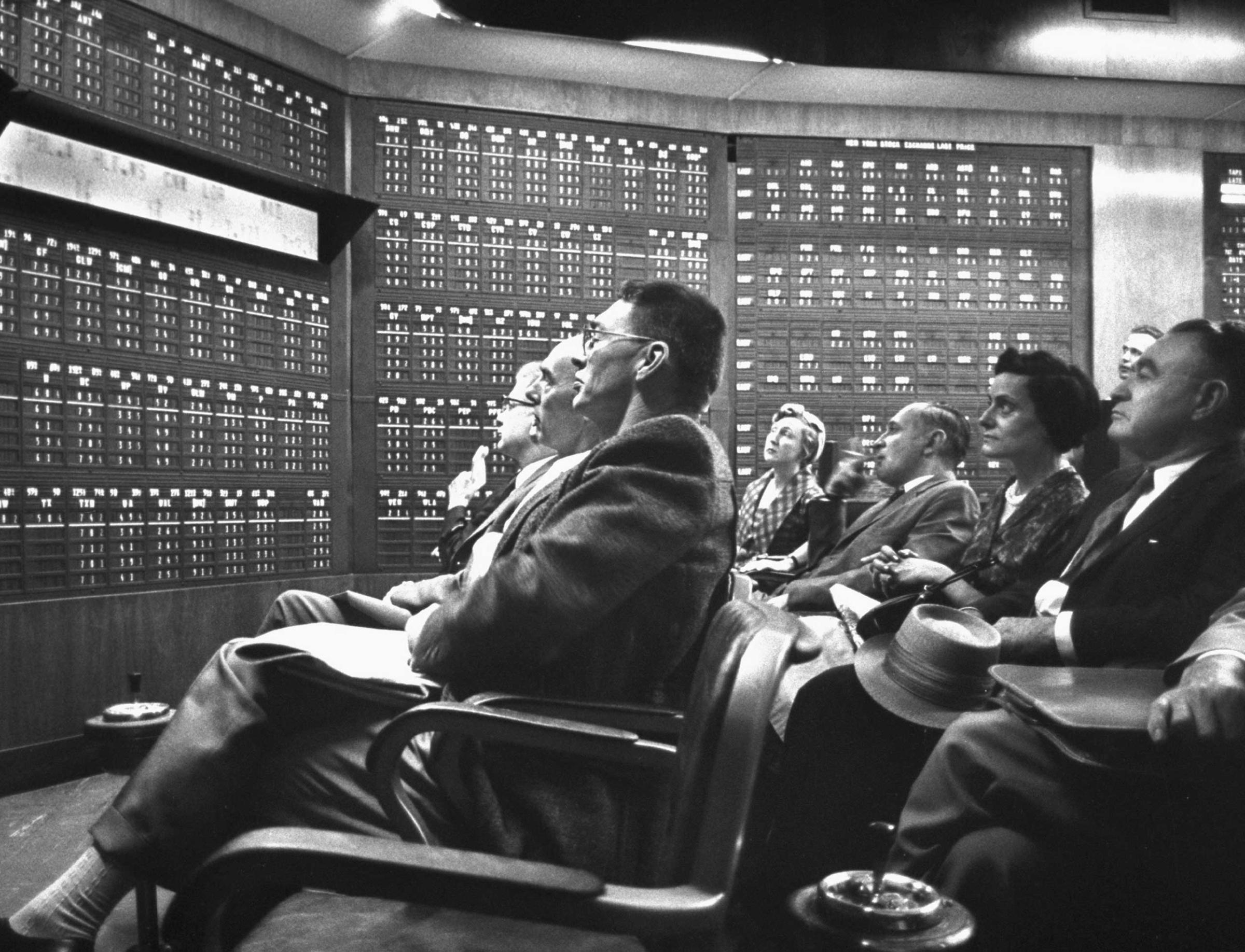

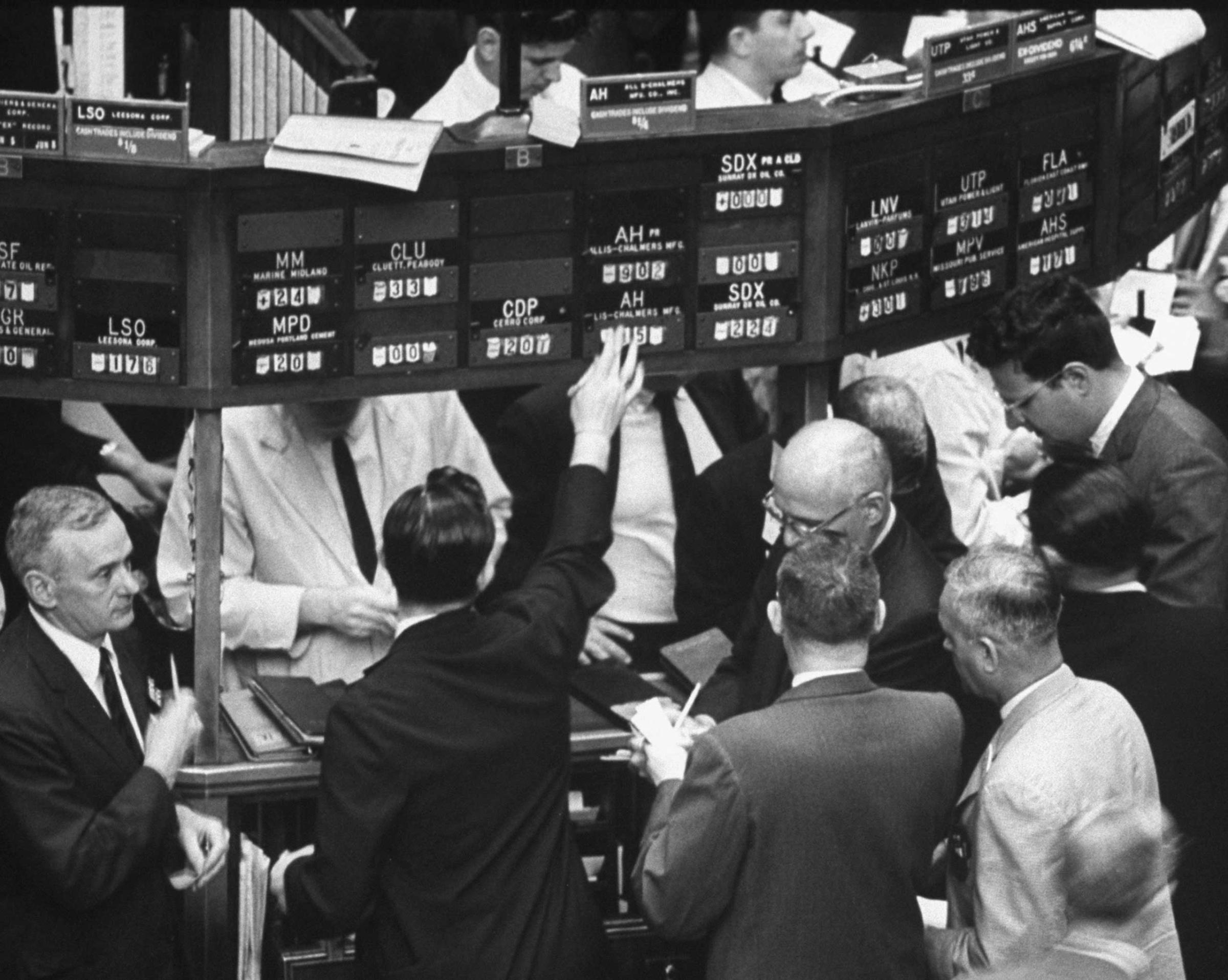

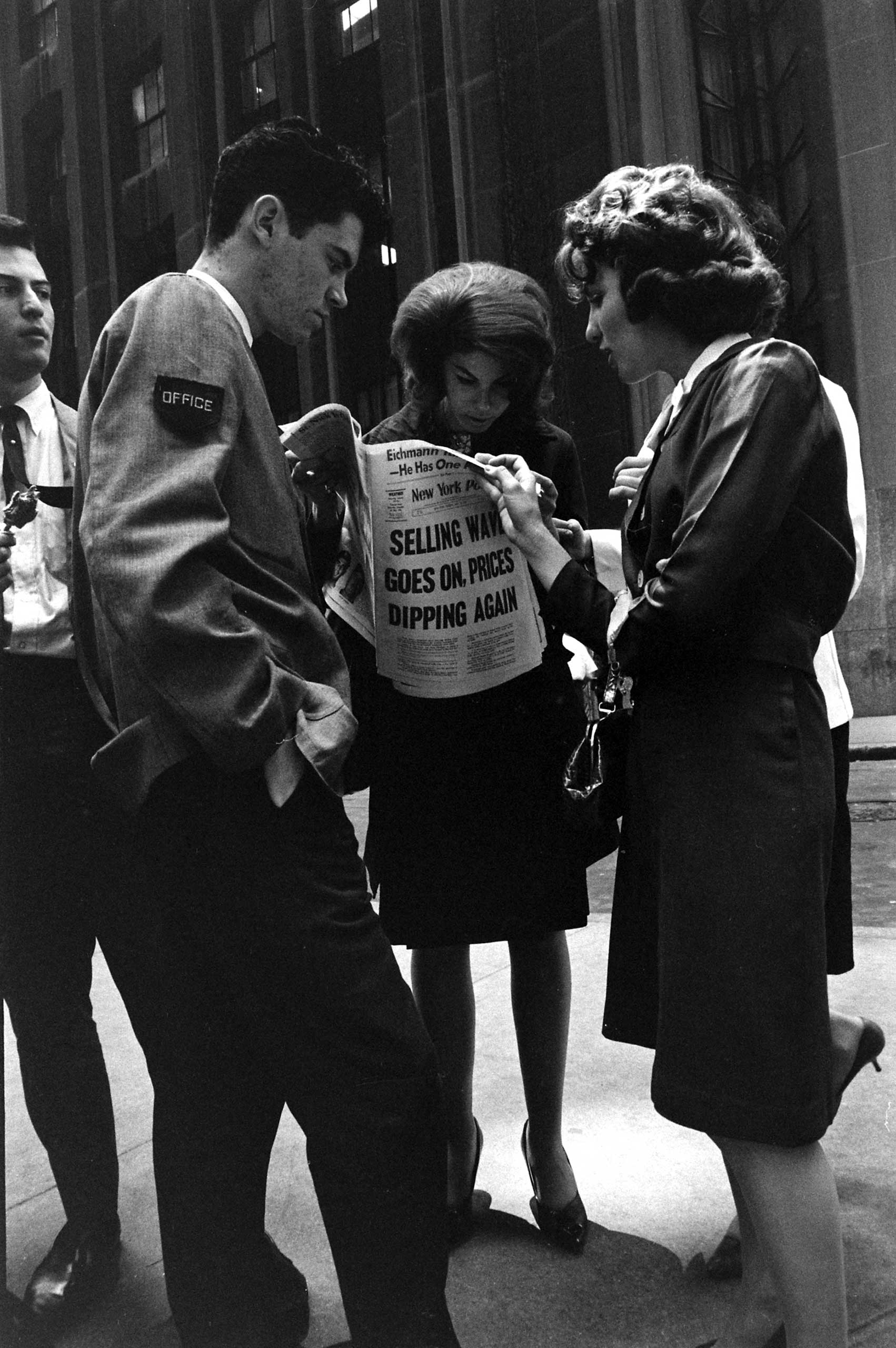

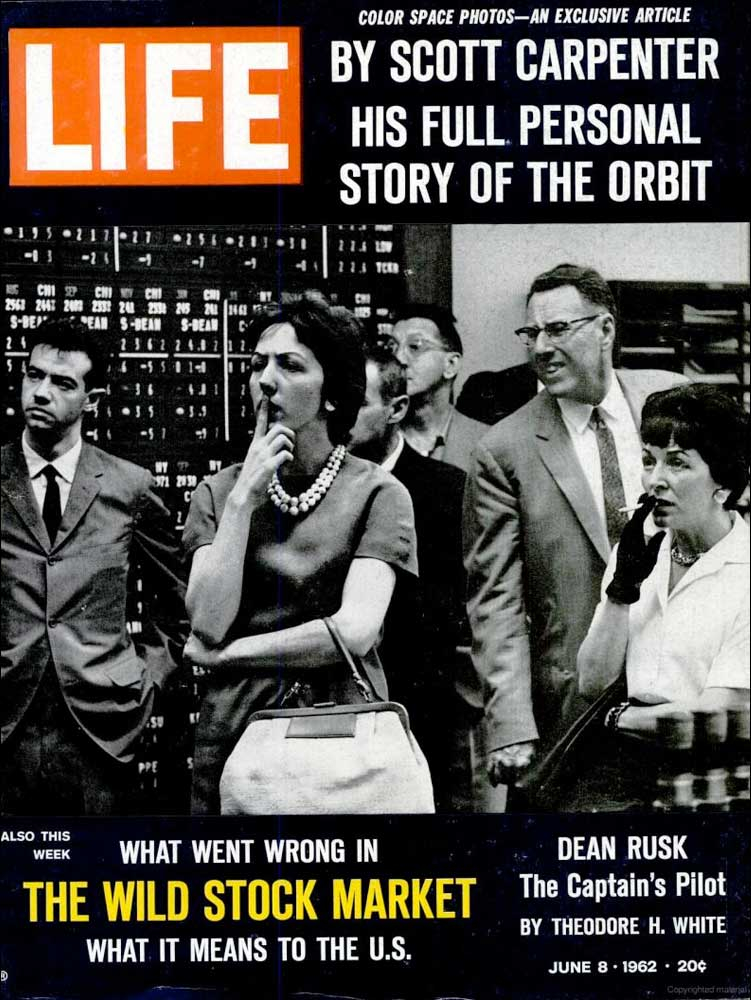

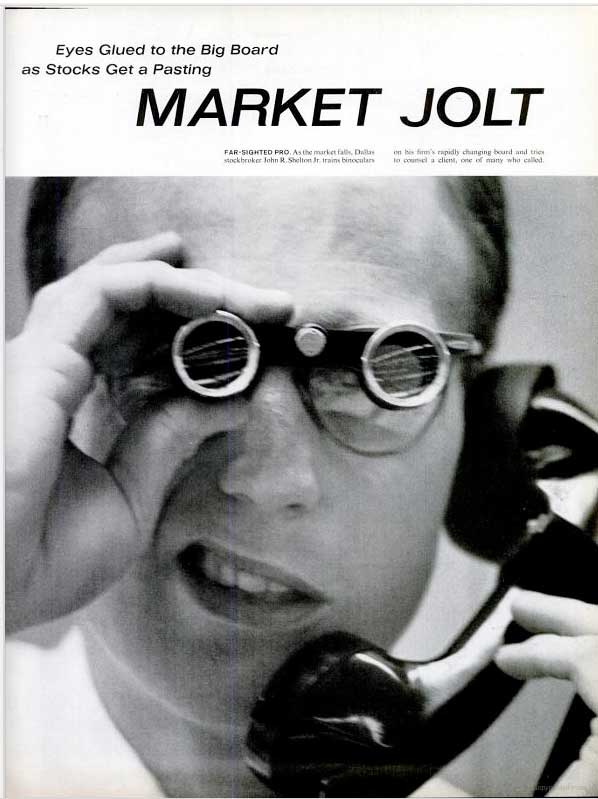

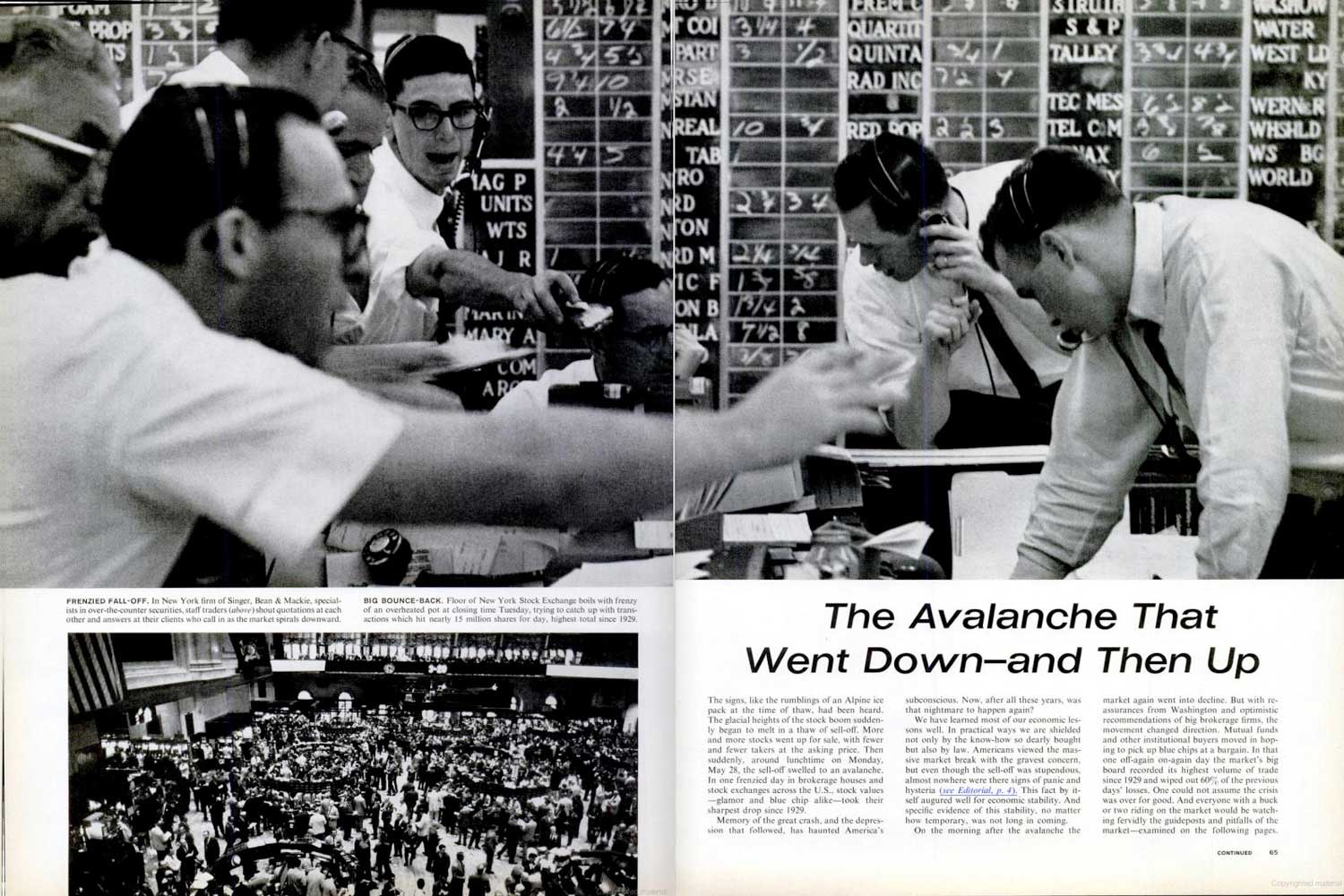

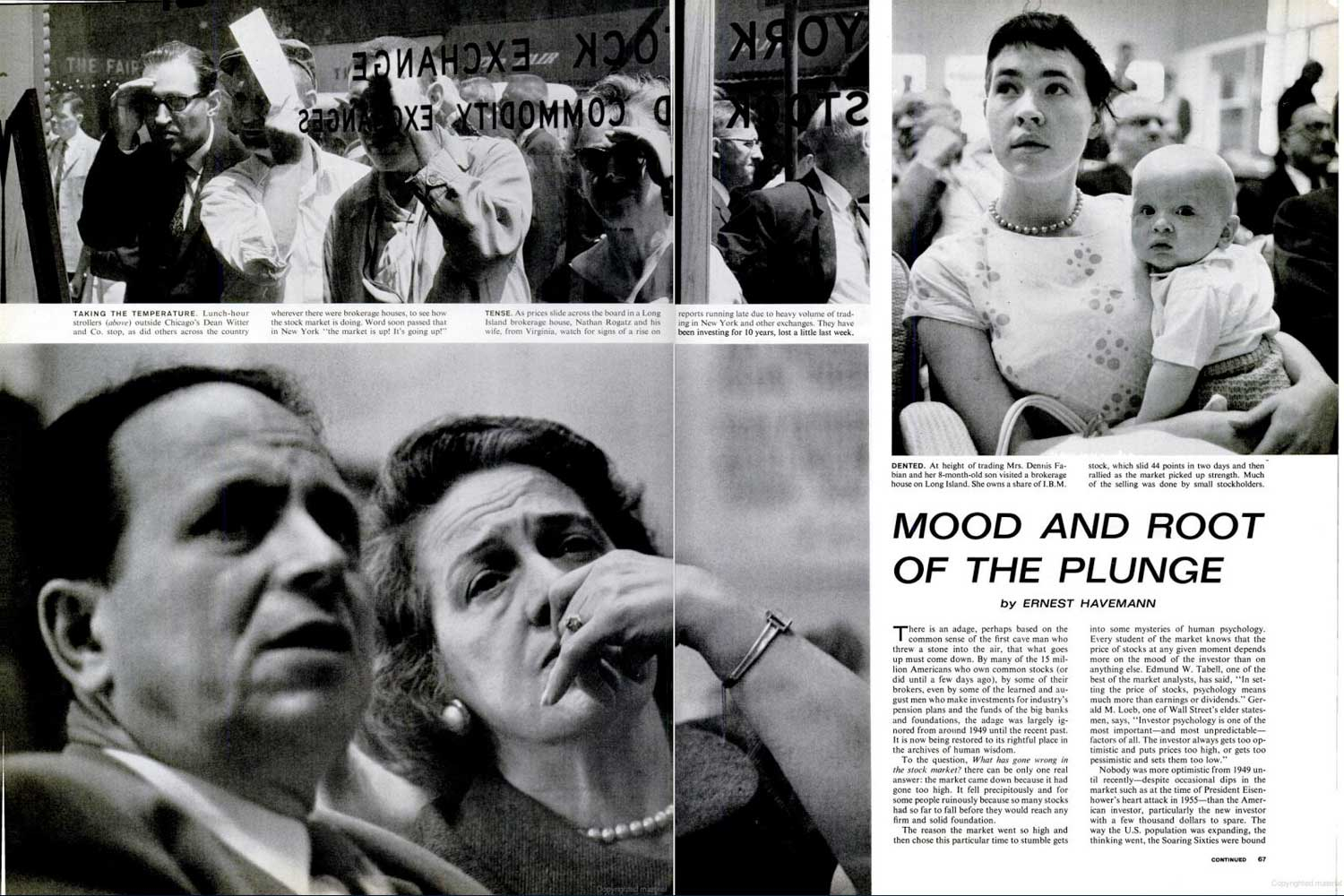

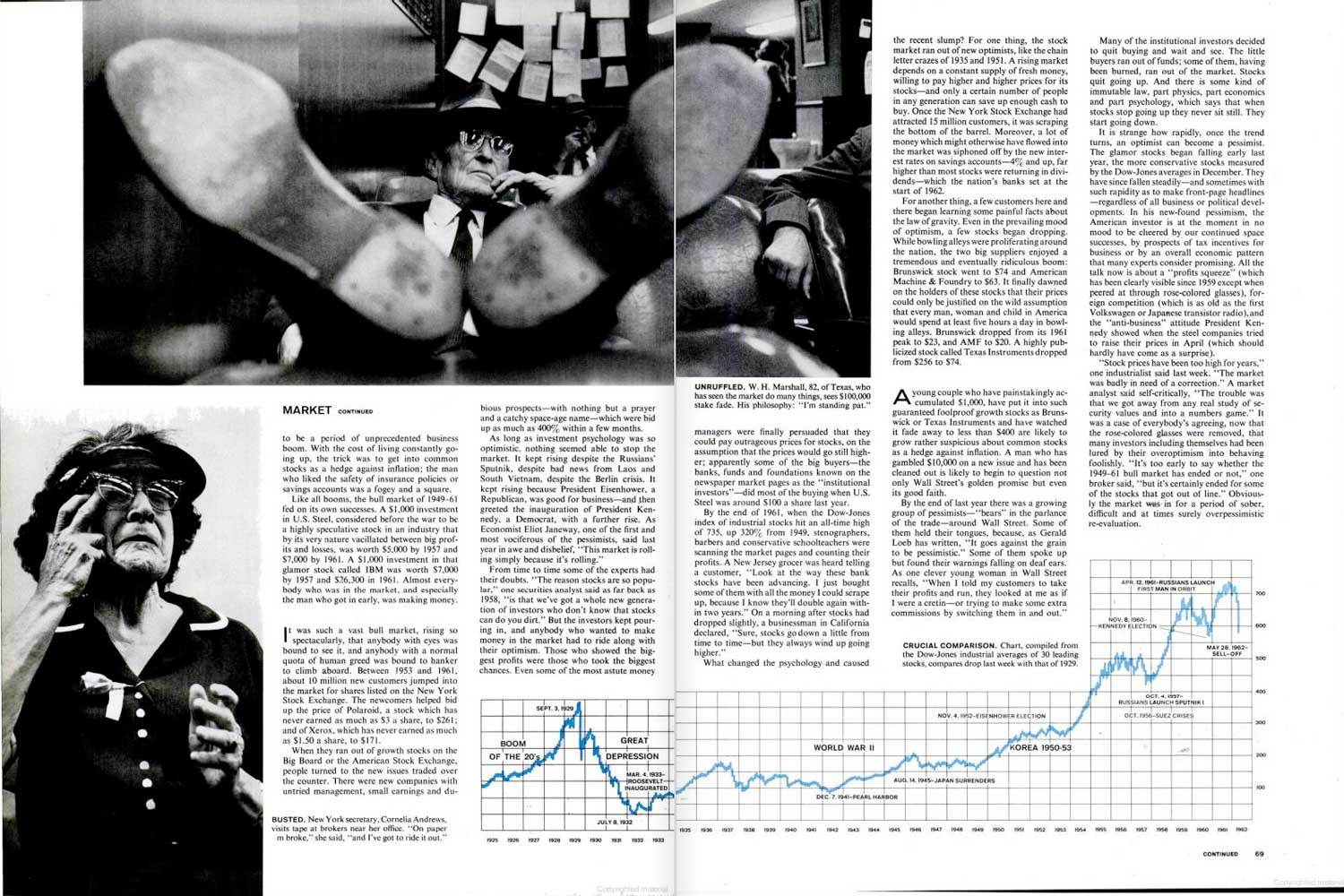

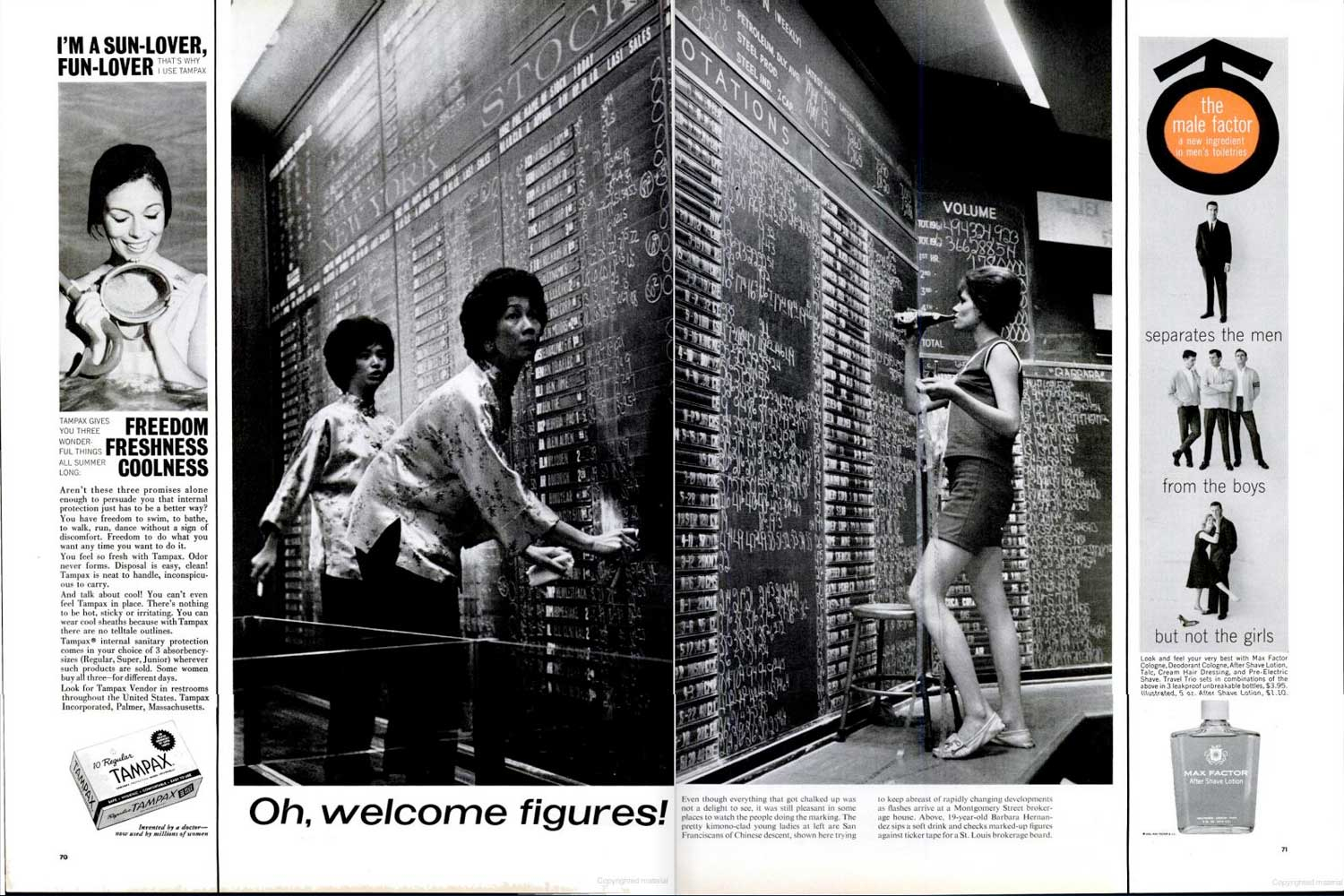

Market Woes: Remembering the ‘Flash Crash’ of 1962

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com