The holy grail of world-building games, it’s argued, is a black box that lets players do as they like with minimal handholding. Pliability with just the right measure of accountability. Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, a tactical stealth simulation wrapped in a colossal resource management puzzle inside a love letter to theatrical inscrutability, comes the closest of any game I’ve yet played to realizing that ideal.

That probably sounds a little backwards if you’re hip to Hideo Kojima’s long running Metal Gear Solid series, which launched in 1987 on a Japanese computer platform. We laud Kojima for his contributions to stealth gaming’s grammar, but he’s also loved and, by some, lampooned, for bouts of indulgent auteurism. A self-professed cinephile (he told me in 2014 that he tries to watch a movie a day), he’s notorious for straining attention spans with marathon film-style interludes and epic denouements. His last numbered Metal Gear Solid game, Guns of the Patriots, holds two Guinness records, one for the longest cutscene in a game (27 minutes), another for the longest cutscene sequence (71 minutes). A fan-edited compendium of the latter’s combined non-interactive sequences clocks in at upwards of nine hours.

So it feels a little weird to declare The Phantom Pain comparably cutscene-free. Oh they’re still here, as fascinating, offbeat and abstruse as ever, but restricted to momentary exposition instead of Homeric interruption. It’s like some other mirror-verse version of Kojima helmed production, suddenly obsessed with play-driven storytelling, while most of the grim narrative about the descent of a Melvillian mercenary trickles in through cassette tapes you can listen to at leisure, or ignore completely.

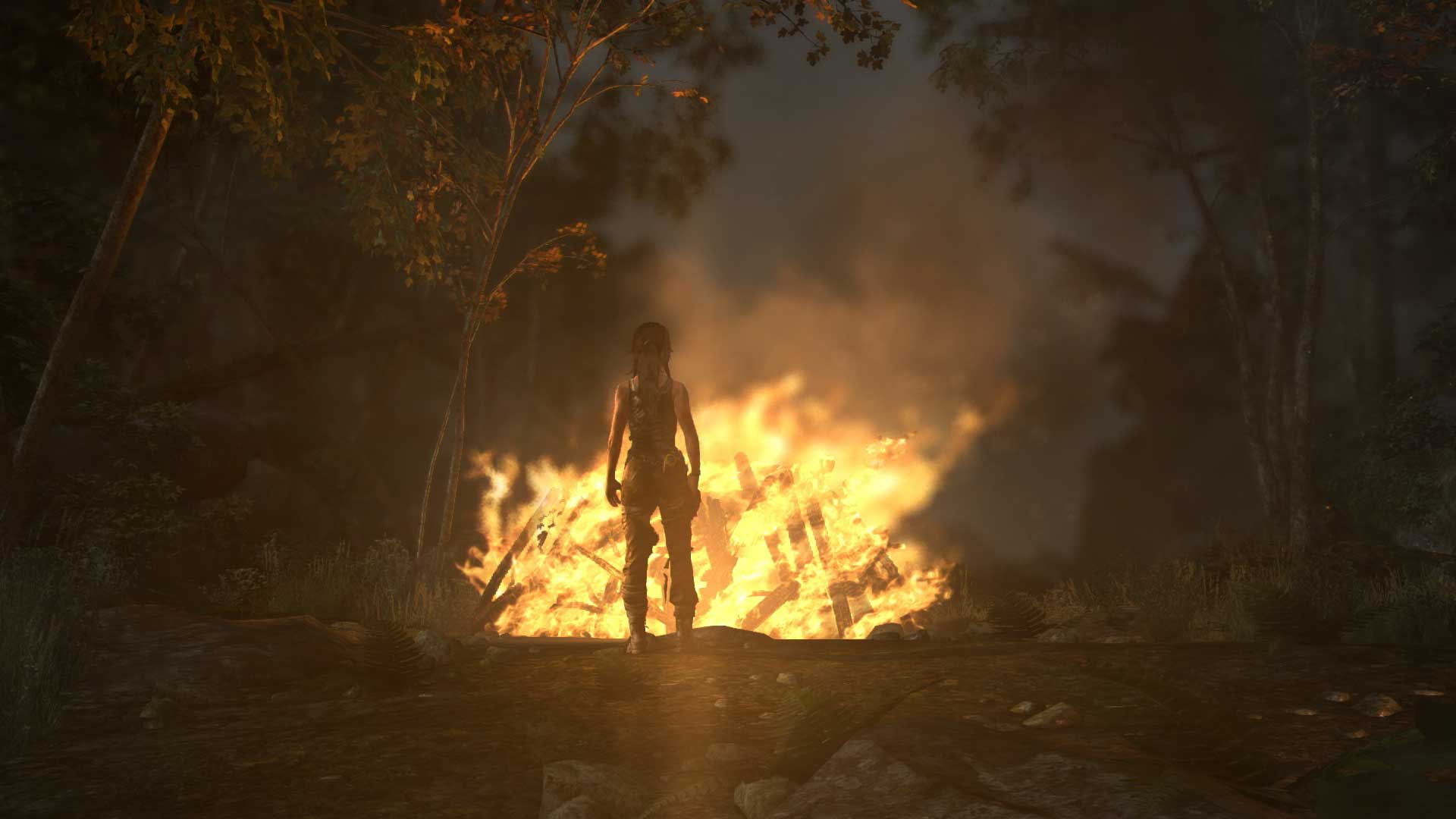

That turnabout pays dividends. We’re instead treated to a clandestine feast of open world prowling, an unparalleled tactical toybox staged in sprawling bulwarks bristling with eerily sentient enemies. You play as Big Boss, the grizzled, cyclopean soldier of fortune we spent so much of the series reviling, traumatized and left comatose by events in last year’s prologue and prolegomena, Metal Gear Solid: Ground Zeroes. The Phantom Pain is the revenge fantasy entrée transpiring nine years later, a grab-your-bootstraps offshore empire-building exercise and parallel slide into militaristic perdition by way of the Soviet-Afghan and Angolan (civil) wars circa 1984. It’s a Cold War paranoiac’s paradise.

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

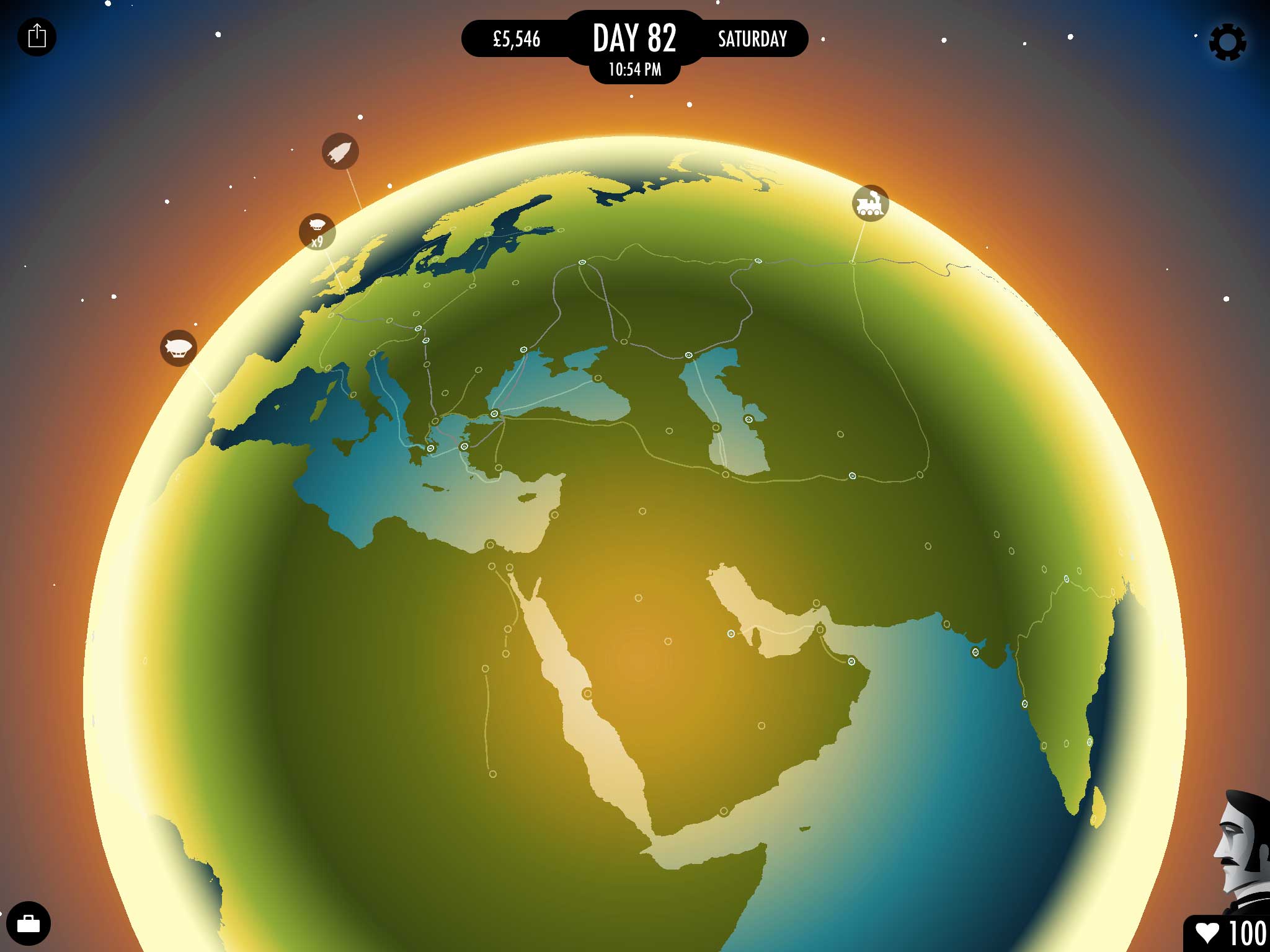

The idea, first articulated in 2010’s Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker, is that you’re leading a private nation-agnostic military force from your “mother base,” a concrete and steel-jacketed platform anchored in the middle of the Indian Ocean near the Seychelles archipelago. From there, you execute contracts for shadowy clients in fictional swathes of Afghanistan and the African Angola-Zaire border region, accruing capital to unlock an arsenal of espionage munitions, all the while sleuthing for intelligence on the sinister outfit that brought you to ruin nearly a decade ago.

You’d think a game about private mercenaries would entail managing squadrons of them, and The Phantom Pain does eventually unlock a meta game where, wielding an anachronistic wireless handheld drolly dubbed an “iDroid,” you can deploy groups of soldiers to conflict zones based on probabilistic projections. But this is Big Boss’s story, and the lion’s share plants you in his boots, embarking on missions framed like TV episodes, infiltrating then exfiltrating enemy compounds, mountain fortresses and repurposed ancient citadels to extract some piece of intel, rescue a skilled soldier or assassinate whatever operative. It’s during those tense, punishing, exquisitely crafted sorties that the experience shifts from glorified hide-and-seekery to sublime subterfuge.

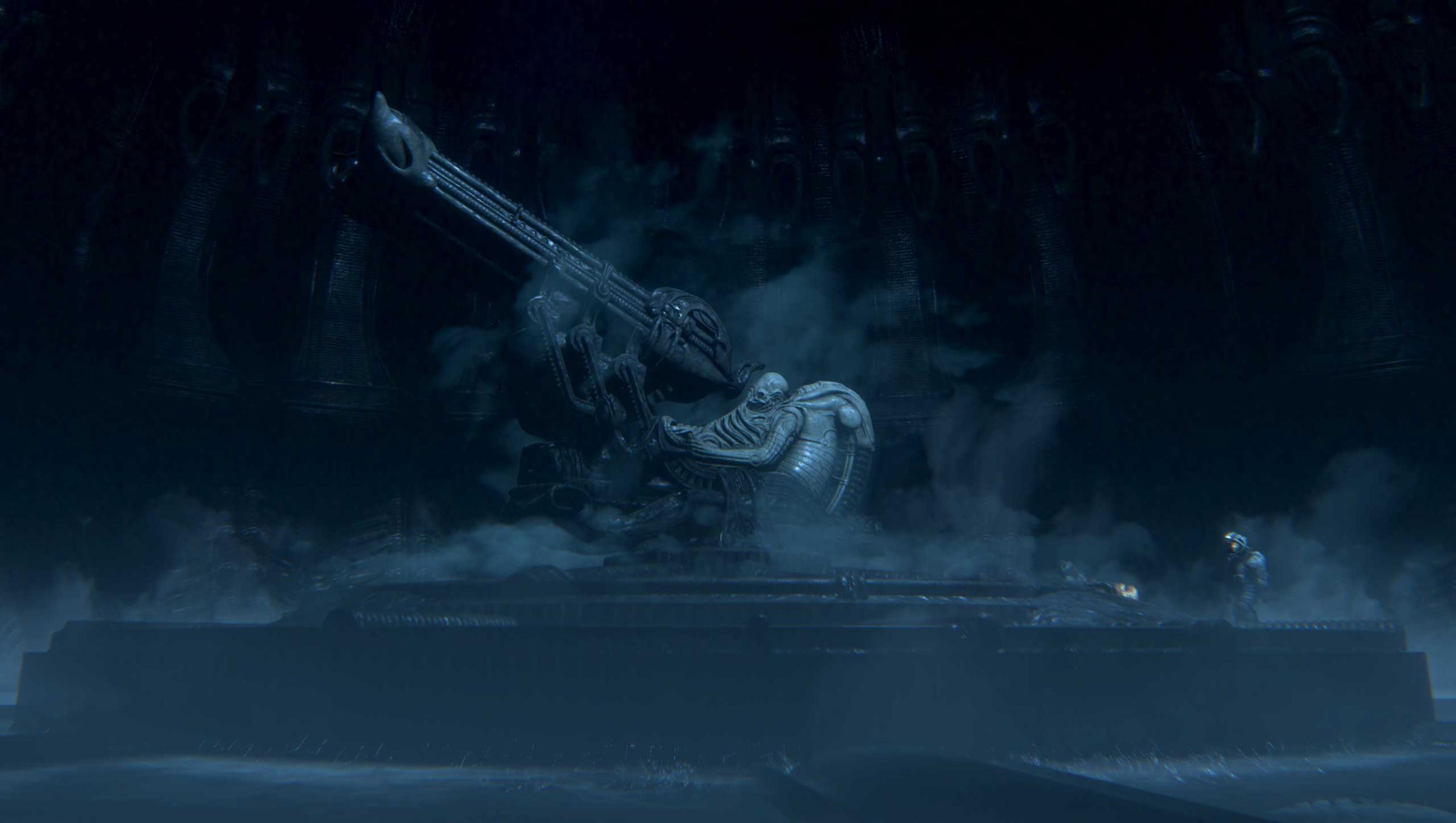

Consider just a few of the ways Kojima lets you poke his anthills. Like how to approach a cliffside fortress teeming with floodlights, security cameras, anti-aircraft cannons, machine gun nests, barbed wire fences, lookout posts, labyrinthine caverns, hovering gunships, weaponized bipedal robots and playgrounds of scalable, multilevel mud-rock dwellings staffed by relentless, hyperaware soldiers. From what angle? At sunrise or sunset? After thorough or slapdash surveillance? In what sort of camouflage? With the aid of a horse for quick arrival and escape, or a canine pal that can spot and mark enemies faster and more completely than you?

Should you wait for a stray sandstorm to blow through, occluding visibility and making direct approaches (or escapes) tenable? Buzz HQ to chopper in a rocket launcher so you can take out an enemy gunship while it’s still on the helipad? Scout for unguarded power hubs to kill lights and cameras (at the expense of raising guard alert levels)? Detonate communications equipment to disrupt radio chatter between field operatives and HQ? Should you slink across a dangerously unconcealed bridge to save time, or clamber down a rocky bluff, scurry across the basin below, then inch up half a dozen flights of steel-cage stairs to pop out at the bridge’s far side? Are you the turtle or the hare?

But it’s the game’s ruthless artificial intelligence that ties it all together so superbly. The Phantom Pain sports the most unpredictable, exploitation-resistant opponents we’ve seen in a sandbox game. Though they run through all the classic Metal Gear-ish paranoia loops, they’re capable of far grander collaboration and topographical awareness. If alerted, they’ll swarm your last known position, then spread out to probe logical escape routes. Favor night ops and they’ll don night vision goggles. Favor headshots and they’ll start wearing metal helmets. It’s as impressive, in its way, as Monolith’s Nemesis system in last year’s Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor, turning indelibility into tactical iteration.

In the background sits your mother base, visually emblematic of Kojima’s fondness for pumpkin-orange containers and pipe-strung sidewalls, everything smooth and orthogonal and gleaming—the Jony Ive of offshore platform design. Once you’re using the Fulton recovery system, an intentionally silly balloon-driven means of quick-firing anything (enemies, weapons, animals and more) you find in the field back to base, you’ll spend hours here developing new weapons, fiddling with staff assignments and snapping on new platforms. Once you grok how battlefield bric-a-brac feeds into base growth, mission difficulty trebles, as you’re incentivized during assignments to track the best-rated foes and gear.

The game has its share of head-scratchers, like why enemies tagged on your radar stay marked when restarting a mission (convenient, but immersion-killing), or why it takes so much work to unlock the game’s notion of a fast travel system. I’m also conflicted about the buddy system: I wound up abandoning my wolf companion because he made the surveillance game too easy.

The least defensible design choice is probably Quiet, a female warrior-sniper dressed in, well, let’s just say the opposite of practical battlefield attire. There’s a plot explanation for this, but it’s pretty weak, though I found it curious that the men in the game seemed not to notice (okay, a couple yahoos overheard talking about her, but that’s it). It’s Kojima’s directorial eye that lingers voyeuristically here, robbing us of the choice not to leer, daring us not to be titillated.

But then we know by now that Kojima games mean wrestling with paradox. Thematic gravitas versus silly dialogue. Visual revelation versus graphical compromise. Gameplay versus cutscene. Eroticization versus objectification. Antiwar allegory versus lurid violence.

When I asked Kojima what hadn’t changed about gaming over the past several decades, he told me that while the technology had evolved, “the content of the game, what is really the essence of the game, hasn’t moved much beyond Space Invaders.” It’s the same old thing, he said, “that the bad guy comes and without further ado the player has to defeat him. The content hasn’t changed—it’s kind of a void.”

Loping across The Phantom Pain‘s hardscrabble Afghani-scapes, lighting on soldiers bantering about communism and capitalism, playing tapes of cohorts waxing philosophic about Salt II, Soviet scorched earth policies and African civil wars, questioning who I’m supposed to be—sporting metaphorical horn and tail, both hero and villain—all I know is that I’m going to miss the defiance, the daring, the controversy, the contradictions. This, given Kojima’s rumored breach with Konami and his own affirmations about leaving the series, is all but surely his last Metal Gear game, so it’s poetically fitting that it turned out to be his best.

5 out of 5

Reviewed on PlayStation 4

Read next: Here’s How to Upgrade Your PlayStation 4 Hard Drive

Download TIME’s mobile app for iOS to have your world explained wherever you go

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com