Celebrating a country’s birthday or independence typically follows a well-known set of rituals, including fireworks, public festivals and passionate political speeches. Marking the occasion of a country’s collapse, however, is a trickier task, and one that Russians and citizens of the former Soviet Union confront each year on August 29. On that day in 1991, the Soviet Parliament suspended the activities of the country’s Communist Party, effectively pulling the plug on the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) altogether.

Many of those who heard the news that day could not identify a time in their own lives when their country could compete with, let alone surpass, its capitalist rivals. Years of economic stagnation, political corruption and popular unrest had discredited Soviet-style socialism as both an idea and a reality, leaving the country with few options but to enter and adjust to a world of free markets. Leaving behind a past of dashed hopes was not so much a choice as a necessary and final capitulation, the terms of which demanded that Russians not look back for the sake of moving forward.

Soviet defeat, however, was not preordained. Indeed, never did the promises of Soviet socialism and the failures of American capitalism present themselves as tangibly and vividly as they did when American photographer Margaret Bourke-White traveled to Russia in 1930 on assignment for Fortune Magazine, LIFE’s older sibling. Only a few months had passed since the New York stock market came crashing down on October 29, 1929, taking many Americans’ savings and jobs with it. The event left many Americans without basic resources such as food, shelter and medical care, and exposed in stark terms the weakness of the American welfare state.

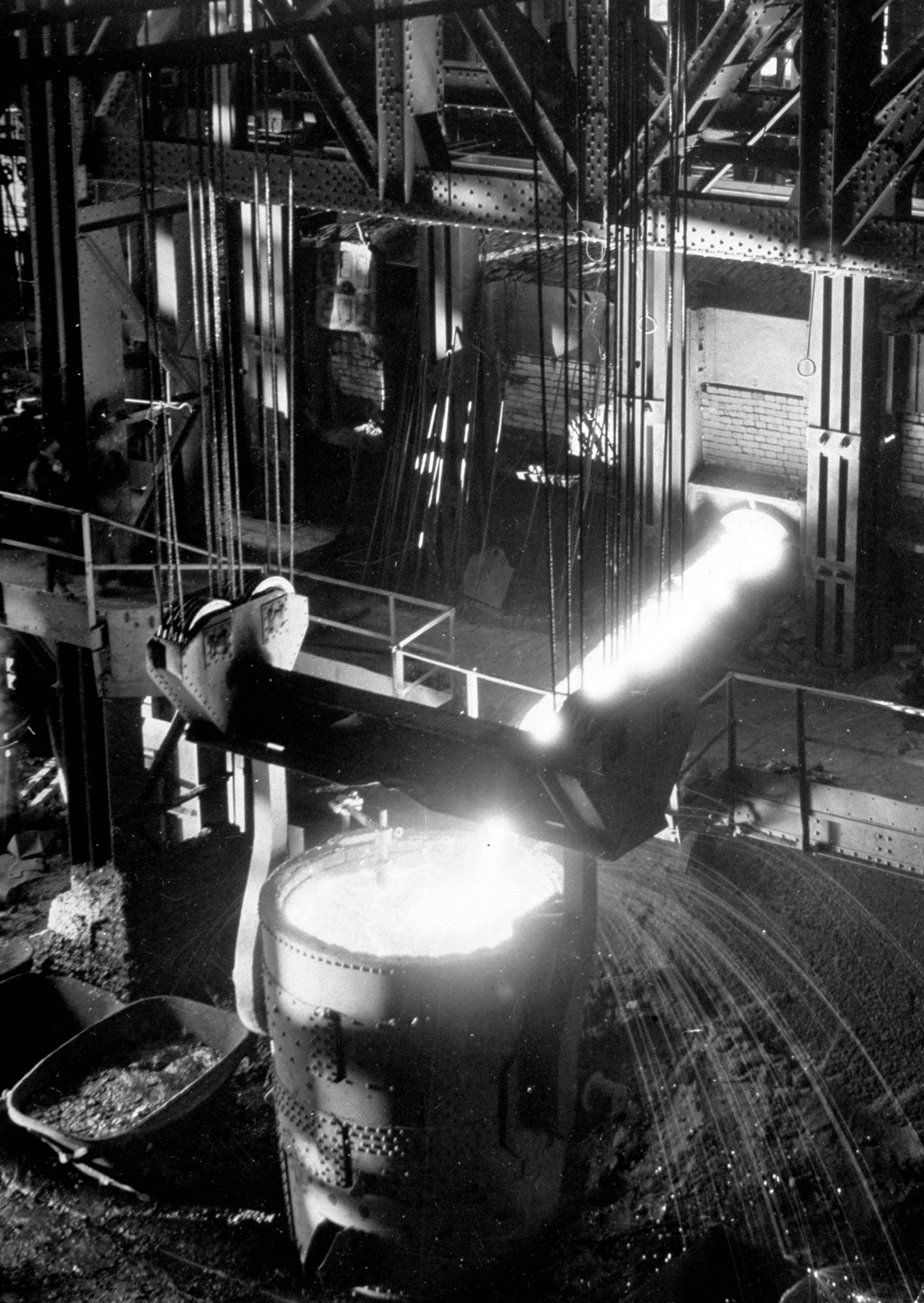

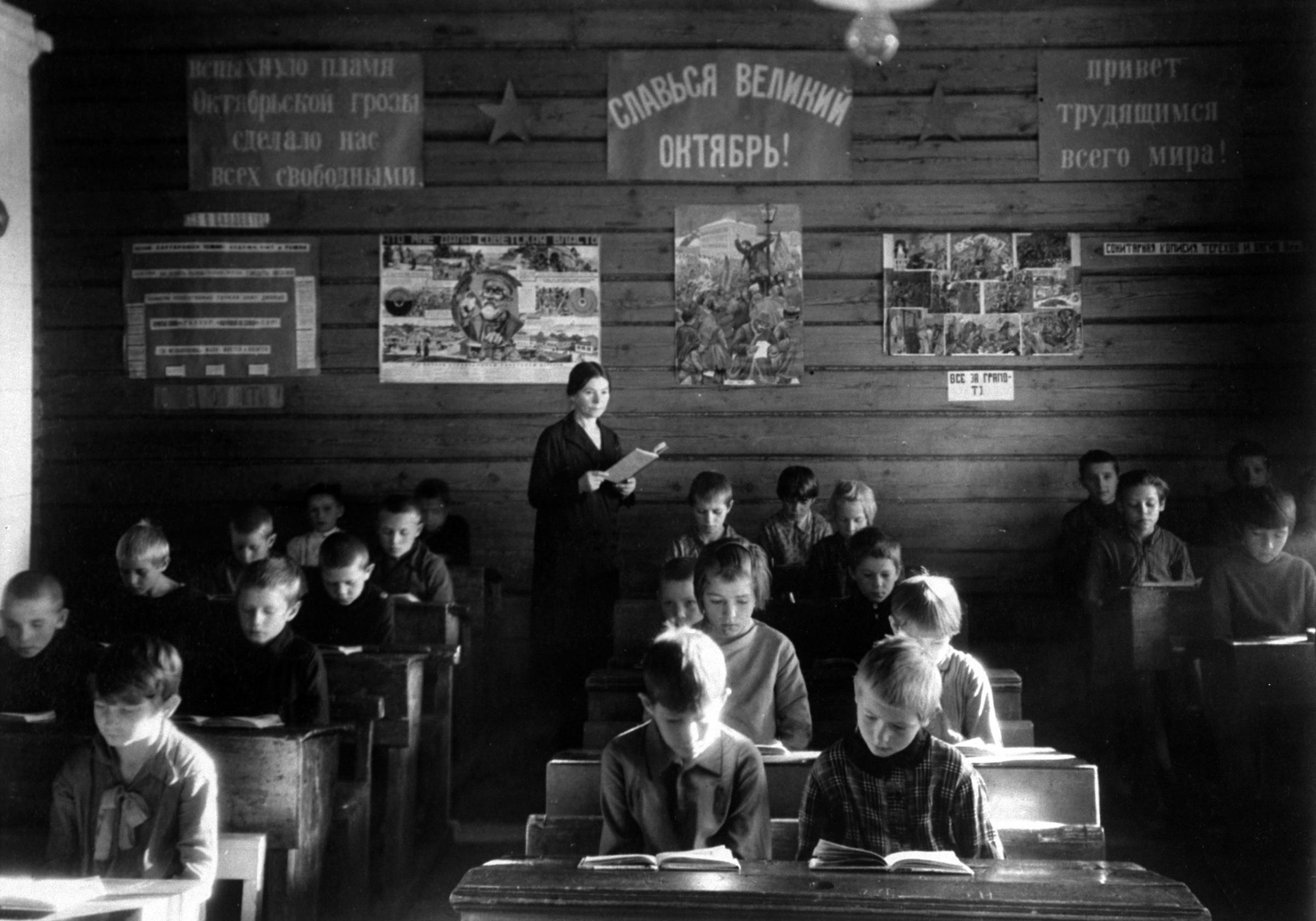

At the same time as breadlines, migrant workers and “Hooverville” tent cities were becoming common fixtures throughout the United States, the Soviet Union was consolidating the gains of its own transformation, one that began in 1928 when Joseph Stalin formally assumed the mantle of the Soviet leadership. Between 1928 and 1932, the Soviet government implemented two large-scale economic projects. First came the Five-Year Plan, an expansive and ambitious industrialization drive designed to shock the country into modernity. Factories, steel mills, hydroelectric dams and bridges popped up on fields, taigas, river beds and lonely mountains, creating more than 25 million industrial jobs for Soviet women and men in the process. Between 1928 and 1940, Soviet annual GNP growth clocked in at an astounding 15%, a rate that dwarfed the 5% annual growth that the United States experienced at the height of its own industrial revolution in the late nineteenth century.

“I saw the five-year plan as a great scenic drama being unrolled before the eyes of the world,” Bourke-White recalled in her book Eyes on Russia, published a year after her initial trip to the USSR. “Things are happening in Russia, and happening with staggering speed. I could not afford to miss any of it.” The black-and-white photographs she took during her 5,000-mile journey throughout the country reflect both the sense of awe she felt as she confronted the colossal building projects and the human toll the changes were taking.

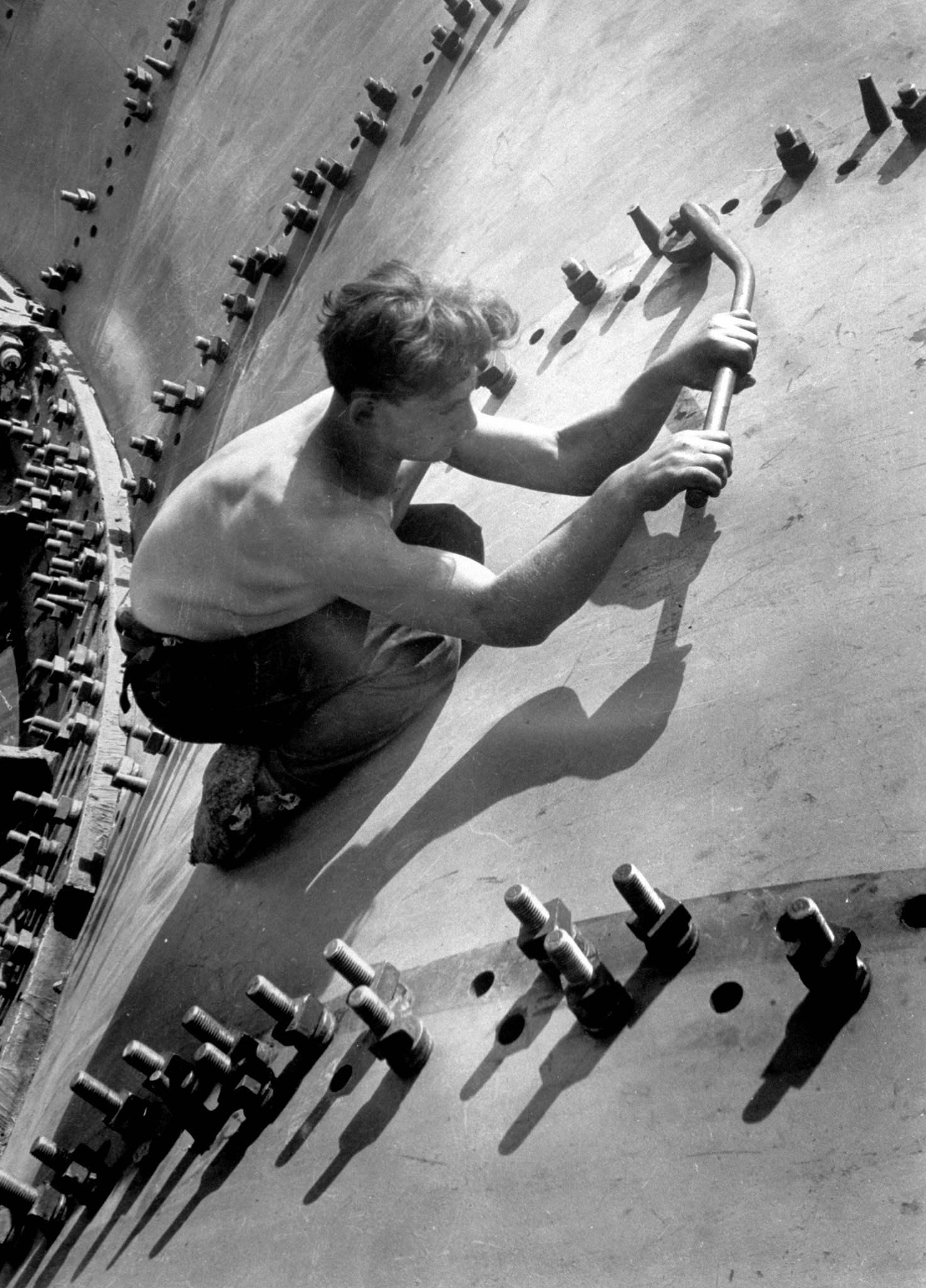

Bourke-White played with perspective to communicate the scope of new construction. A partially built bridge was shot from ground level to enhance its already towering size. A tractor’s gleaming wheels (the “new God of Russia,” as she called it) acquired an exaggerated sense of scale, its human drivers pushed to the image’s far-right corner. Half-built pillars destined to become the main arteries of Central Ukraine’s Dnieperstroi Dam stand side by side, as if they were coming off an assembly line from behind the clouds. “All day long we climbed ladders, planks, and cross beams,” Bourke-White reminisced. “Hanging on to scaffolding, with one arm curved around a beam to steady myself, I photographed the shifting scene.” The entire Soviet Union had become a giant construction site, a sprawling playground for Bourke-White’s lens.

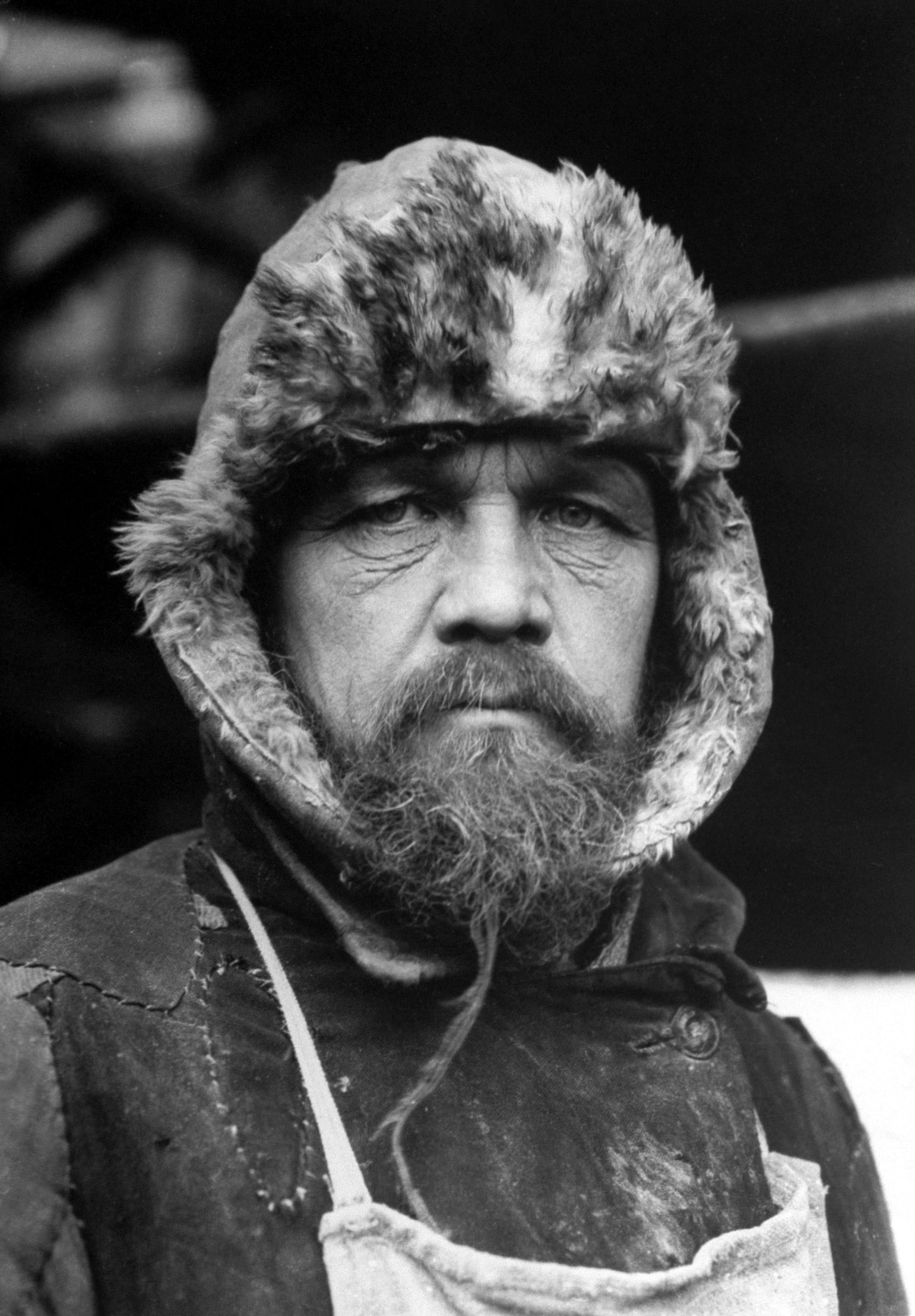

When it came to documenting collectivization, the other half of Stalin’s two-pronged economic policy, Bourke-White placed her human subject front and center. Collectivization, which took place between 1929 and 1931, called for the forced nationalization of the country’s agriculturally productive land and their subsequent division into state and collective farms. Stalin reasoned that nationalizing agriculture would make it easier to collect harvested crops and feed the country’s exponentially multiplying industrial workforce. The gamble intentionally privileged the wellbeing of his prized industrial workers at the expense of the peasants whose land and output would ultimately be seized. Famine, violence, and mass dislocation wreaked havoc throughout Ukraine, the North Caucuses and Russia’s Central Volga Region, resulting in the deaths of more than 5 million people by the end of 1932. By the time Bourke-White arrived in Russia, nearly 15 million households had been collectivized and 77 million tons of grain brought in during the 1930 harvest alone.

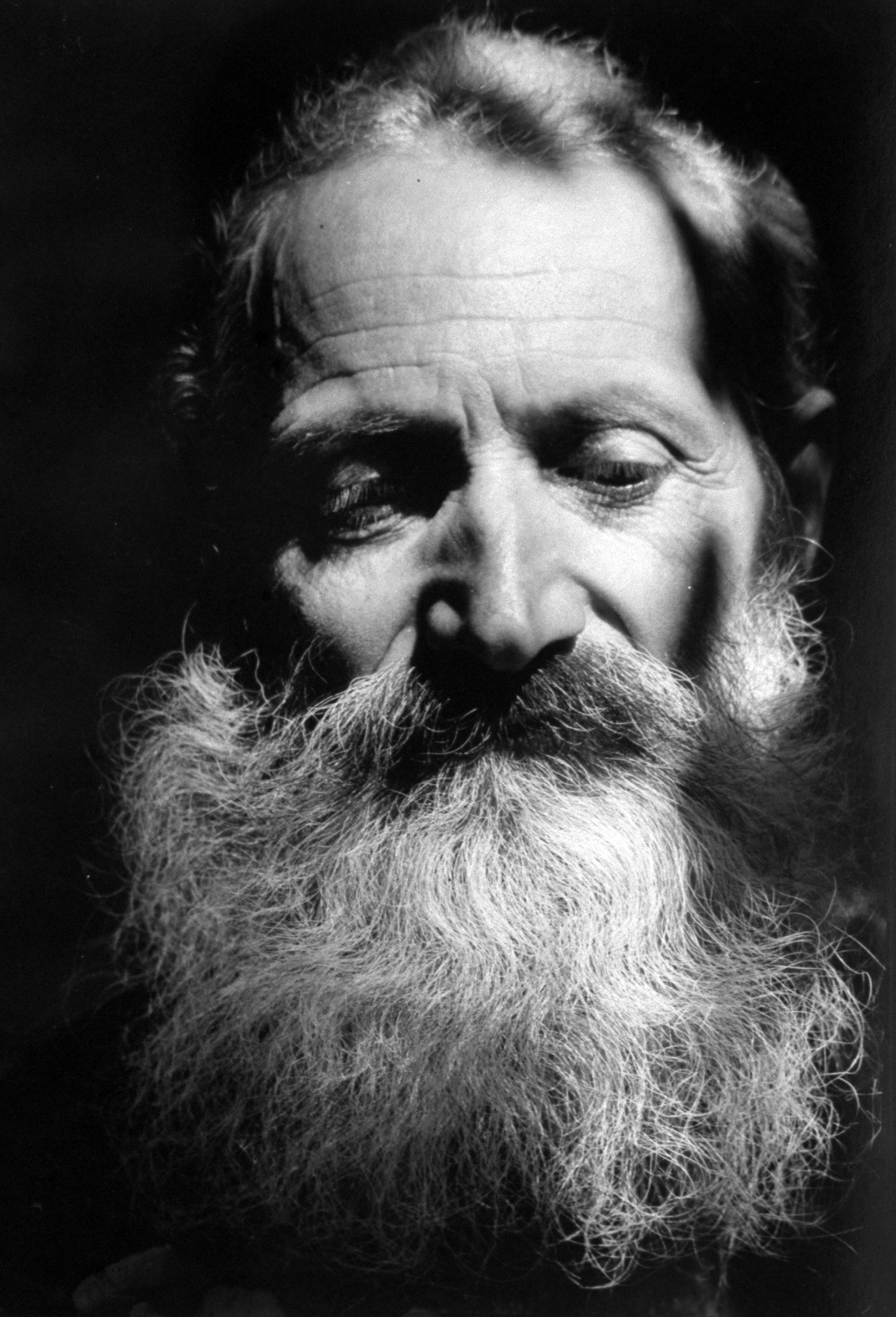

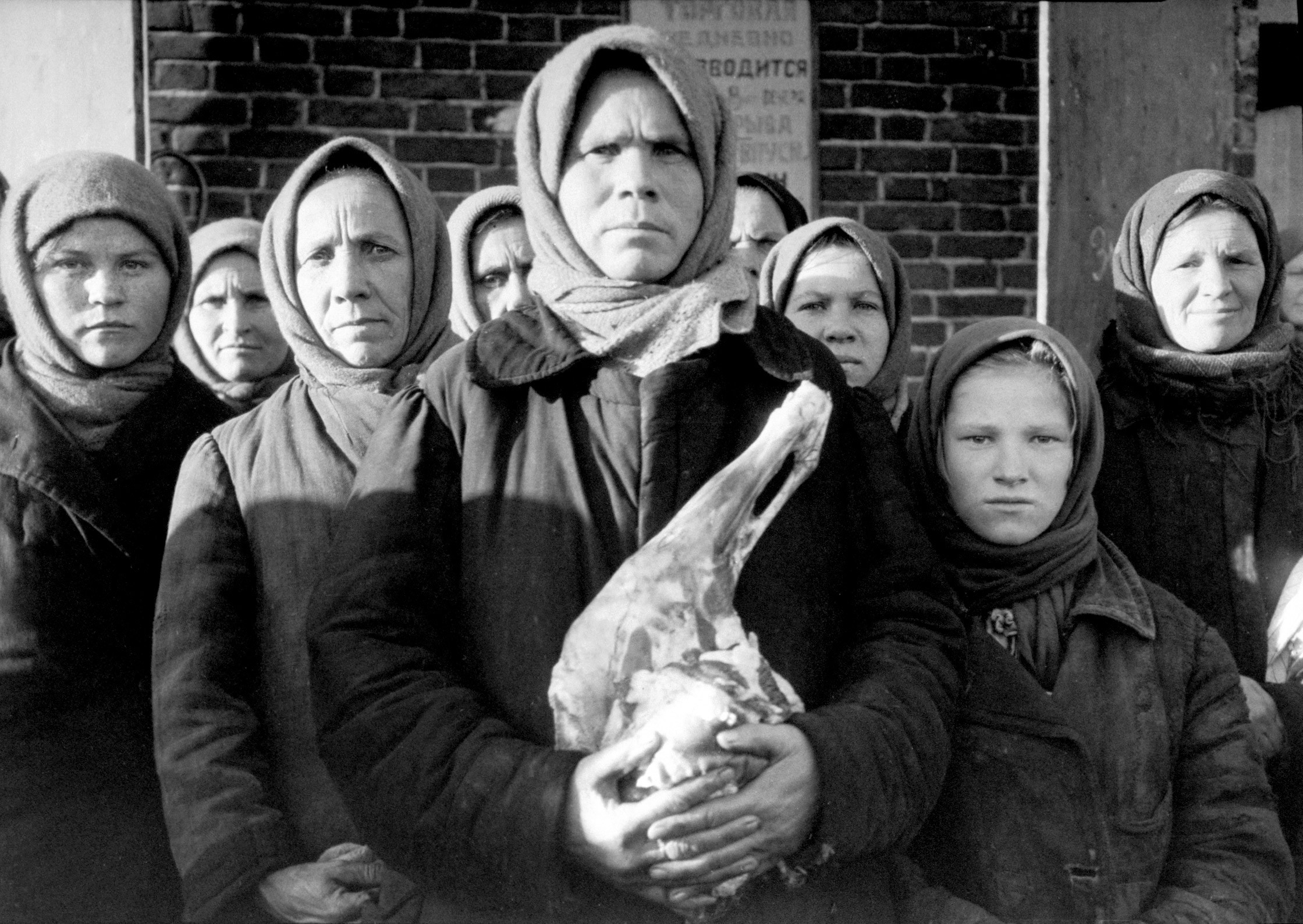

But if Bourke-White saw any of the suffering that attended collectivization, she did not reveal so in words. Only the photographs that she took during her stay at the newly formed state farms provide viewers with clues to her experience as a witness to perhaps the most revolutionary of Stalin’s experiments. An image of a Russian woman standing in front of a warmly dressed crowd, a single slab of meat wrapped tightly in her arms, signals to the viewer that the winter of 1930 was not a kind one. A portrait of a bearded Russian priest posing for Bourke-White’s camera with downcast eyes hints to the hardship he may have been experiencing in the wake of the government’s ban on formal religious practice.

A photograph of a man and woman standing in a state farm field, looking out into the cloudy abyss as a tractor rests nearby, speaks to the overwhelming exhaustion that Bourke-White’s subjects most likely felt when they contemplated the enormous task they were being asked to undertake. Those who see this image today may find it familiar. Indeed, its composition echoes those of the photographs that Bourke-White and other American photographers like Dorothea Lange would later take of Depression-era sharecroppers, displaced farm families and migrant workers while working for the New Deal’s Farm Securities Administration.

Unlike the elaborate parades staged in Red Square this past May to commemorate the 70th anniversary of German surrender on the Eastern Front, the collapse of the Soviet Union is celebrated individually and quietly. Some Russians may take a moment to reflect on their family’s history during the Soviet years, while others may feel relief that the socialist chapter of Russia’s history has ultimately closed. Many will go about their day without realizing what August 29 represents. In many ways, Russians, and especially Muscovites, confront the history of the Soviet project on a daily basis: as they ride the Moscow metro, walk past the Lenin Mausoleum as they cut through Red Square and spot one or more of the seven Stalinist skyscrapers somewhere in the middle distance, all built as a result of Soviet largess.

When asked why she decided to document the USSR’s industrial revolution back in the 1930s, Bourke-White responded with the following: “I wanted to take the pictures of this astonishing development, because, whatever the outcome, whether success or failure, the effort of 150 million people is so gigantic, so unprecedented in all history, that I felt that these photographic records might have some historical value.” If asked today how they feel about the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, many Russians would likely express a similar feeling: they may not know exactly what to make of it, but they know that it was something big.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com