Some Japanese men are wooing girlfriends who don’t exist. While they can only interact with their partner through a pre-written script, these virtual beauties — Rinko, Manaka or Nene — offer a kind of instant emotional connection at the tap of a stylus. The girls can kiss, “hold” a player’s hand, exchange flirtatious text messages and even snap out in anger if the player leaves a conversation. It’s one of Japan’s biggest gaming phenomenons called Love Plus – available on the Nintendo portable consoles and the iPhone.

“There is no friction in these relationships, obviously,” says Loulou d’Aki, a Swedish photographer who documented a number of Japanese players earlier this year. “The girls behave very sweetly with the guys in what they say, how they respond to them, and with big eyes and heart-shaped faces—who wouldn’t want that?”

D’Aki teamed up with Swiss science writer Roland Fischer and together, they sought to go beyond the existing online conversation. “When you Google ‘Japan’ and ‘love’, you find all these articles about lonely people who never get married,” she says. “I didn’t want to reduce it to that. I wanted to show the human aspect, the individual stories behind those who use these applications.”

Her images reveal the secret lives of thirty-somethings who have accepted living alone instead of looking for love. They share a common yearning for connection and found it on a touch screen. Many see it as just a game and can easily distinguish between the computerized and reality, while others are perpetually stuck in a love loop, desperately waiting for the next update of the game.

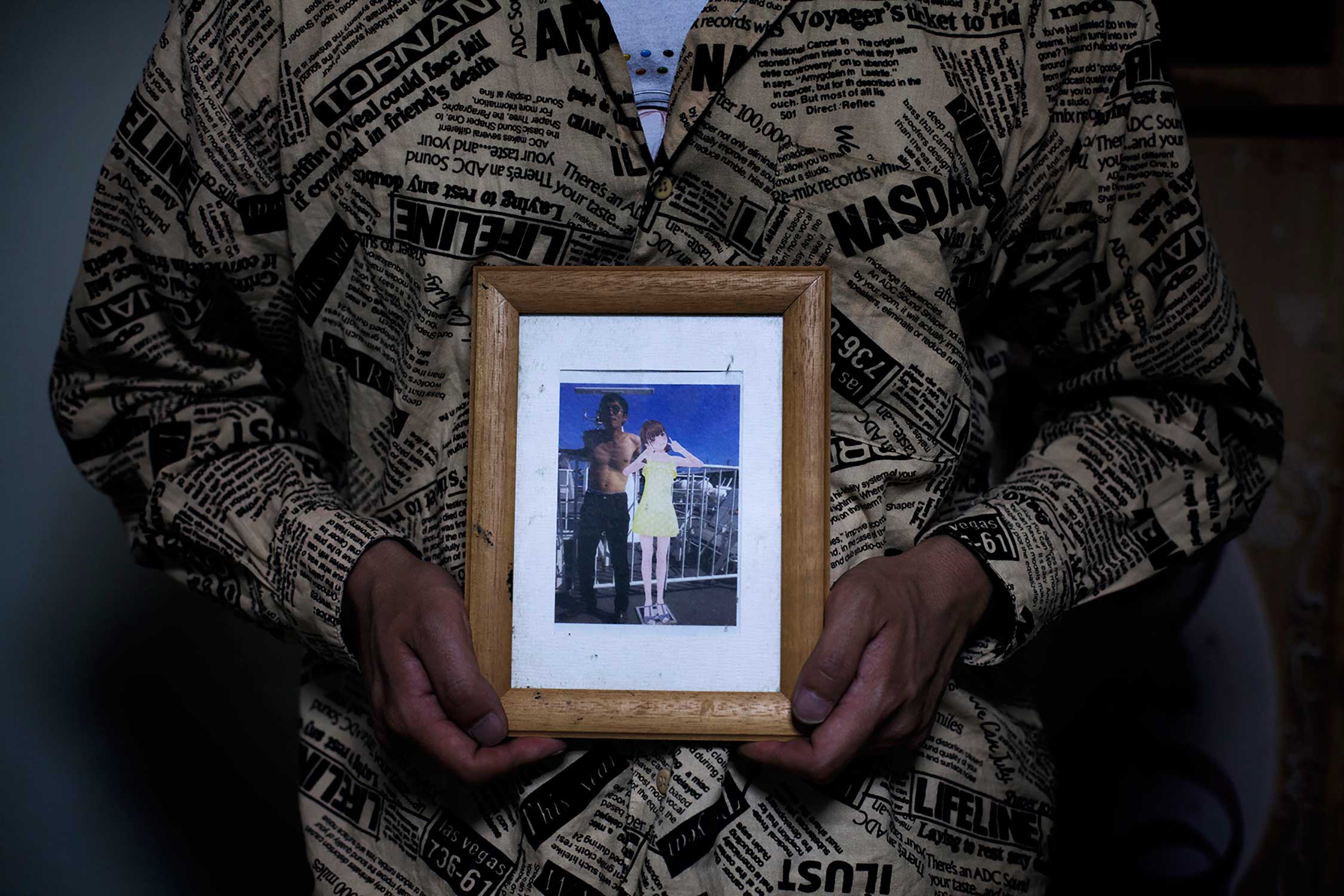

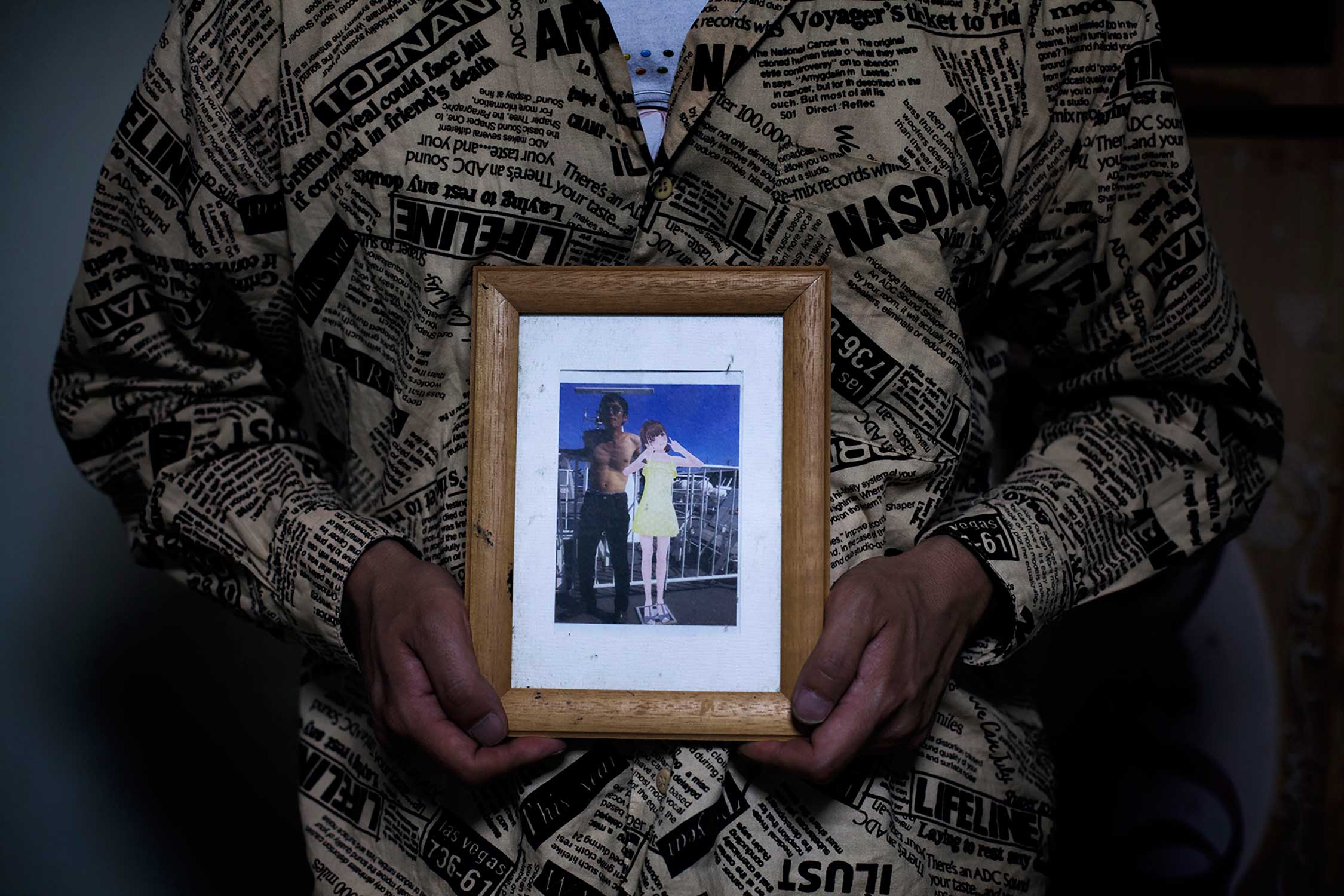

One player holds a picture of him and his virtual girlfriend, Manaka, at a resort town called Atami, which caters to players on a weekend retreat programmed into the game. Another 48-year-old player spends one of many nights alone in his one-bedroom apartment with his console, chatting with Manaka, his e-girlfriend of five years.

Some like Kosaki, stopped playing Love Plus when the Konami, the game’s developer, stopped offering update to the Nintendo DS version. When asked what he was looking for in a woman, he said he wanted someone who appreciates his hobbies. “I thought they would tell me all these physical things like, ‘she has to look like this,’ but nobody said anything like that. They wanted someone who accepted them as they were.”

For others like Masano, who has been dating the character called Rinko since 2009, the ease and surety of a virtual girlfriend qualms the fear of failure in the real dating sphere. “He said something that struck me as a little bit sad,” d’Aki says. “He said, ‘Well, you know all I want is someone to say good morning to in the morning and someone to say goodnight to at night.’”

These feelings are not limited to Japanese men – game developers have also released romance simulations that cater to women . These games are structured to offer a similar experience to reading a 19th-century romance novel, “with the difference that you actually play a part [in the story],” says d’Aki.

These games have remained a distinctly Japanese trend, though. It’s the subset of a growing video game culture that has dominated the country’s development since the 1980s. For d’Aki, it’s easy to see how the game had appeal in Japan. “You have these grown-up men in their suits with briefcases, leaving their corporate jobs to read manga in the metro or play gameboy at an arcade,” she says. “You wouldn’t see that in Europe or America.”

Loulou d’Aki is a Swedish freelance photographer.

Mikko Takkunen, who edited this photo essay, is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @photojournalism.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter @rachelllowry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com