Gordon Parks had been a member of LIFE Magazine’s staff for no more than a month when a tantalizing assignment dropped into his lap. His editors sent him to the small volcanic island of Stromboli, not far off the coast of Sicily, where the Italian neo-realist director Roberto Rossellini was making a film with the actress Ingrid Bergman. Parks’ mission had little to do with the film and everything to do with the love affair between the director and his star, who had left her husband and child for him. It was an international scandal. Bergman’s fans, who perhaps took her recent roles as a nun in The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945) and the virgin saint in Joan of Arc too seriously, had turned on her. Knowing that a good scandal can drive sales, magazines and newspapers throughout Europe and the United States were locked in a fierce competition to get the first photographs of the couple in an embrace.

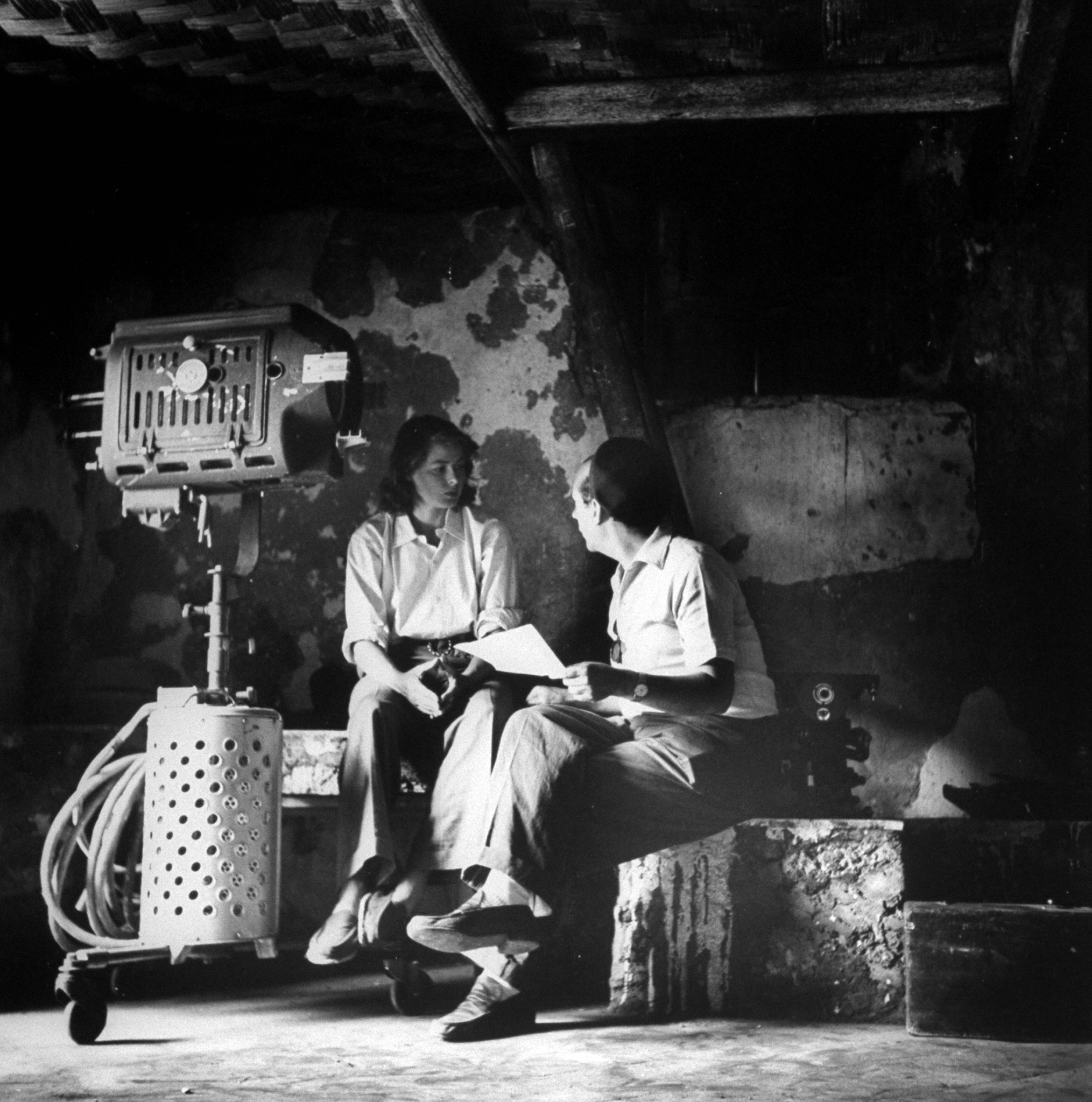

As Parks told the story in his various memoirs, he and Maria Sermolino, a writer from LIFE’s Rome bureau, arrived on the island just in time to watch Rossellini, in a fit of exasperation, order the press away. Rossellini, Parks said, ruled the island like a dictator. But he allowed Parks and Sermolino to stay, and that was due entirely to Bergman’s intervention.

Bergman had been impressed with the sensitivity that Parks brought to “Harlem Gang Leader,” a photo essay that he had photographed for LIFE as a freelancer in 1948. She felt that she could trust him to treat her and Rossellini with respect. (Bergman was not the photo essay’s only fan. It had won Parks his permanent position at the magazine.) In Voices in the Mirror, a memoir, Parks wrote that he was well aware of the bind that she created for him. LIFE’s editors wanted what the world wanted—“that unguarded moment of passion.” “If the moment arrived,” he wrote, “either LIFE or the melancholy lovers would suffer.”

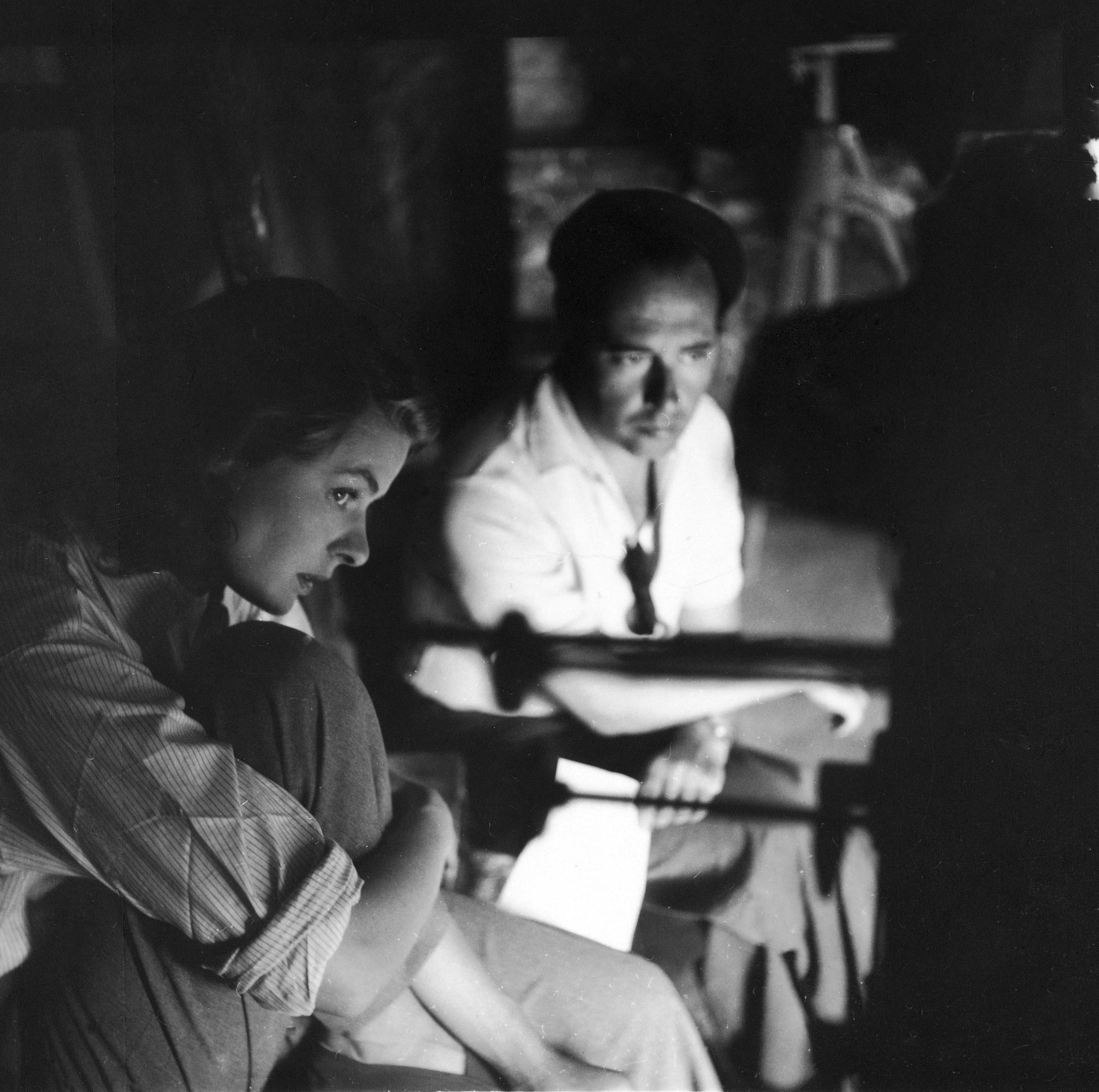

When the chance to betray Bergman presented itself, Parks let it pass. After a day’s filming had ended, he entered the darkened set and found her and Rossellini holding each other in an intimate embrace, one that was “comforting rather than… lustful.” It was the kind of “unguarded moment” that he was on the island to capture. He began to raise his camera, but immediately put it down and left the room, hoping that neither of the lovers had noticed his presence. “The moment that slipped away,” he wrote, “was undeserving of betrayal.”

Bergman had noticed, however, and she was grateful. A few days later, she invited him to follow along as she and Rossellini walked along the island’s shore. On their own terms, they gave Parks the photographs that his editors wanted.

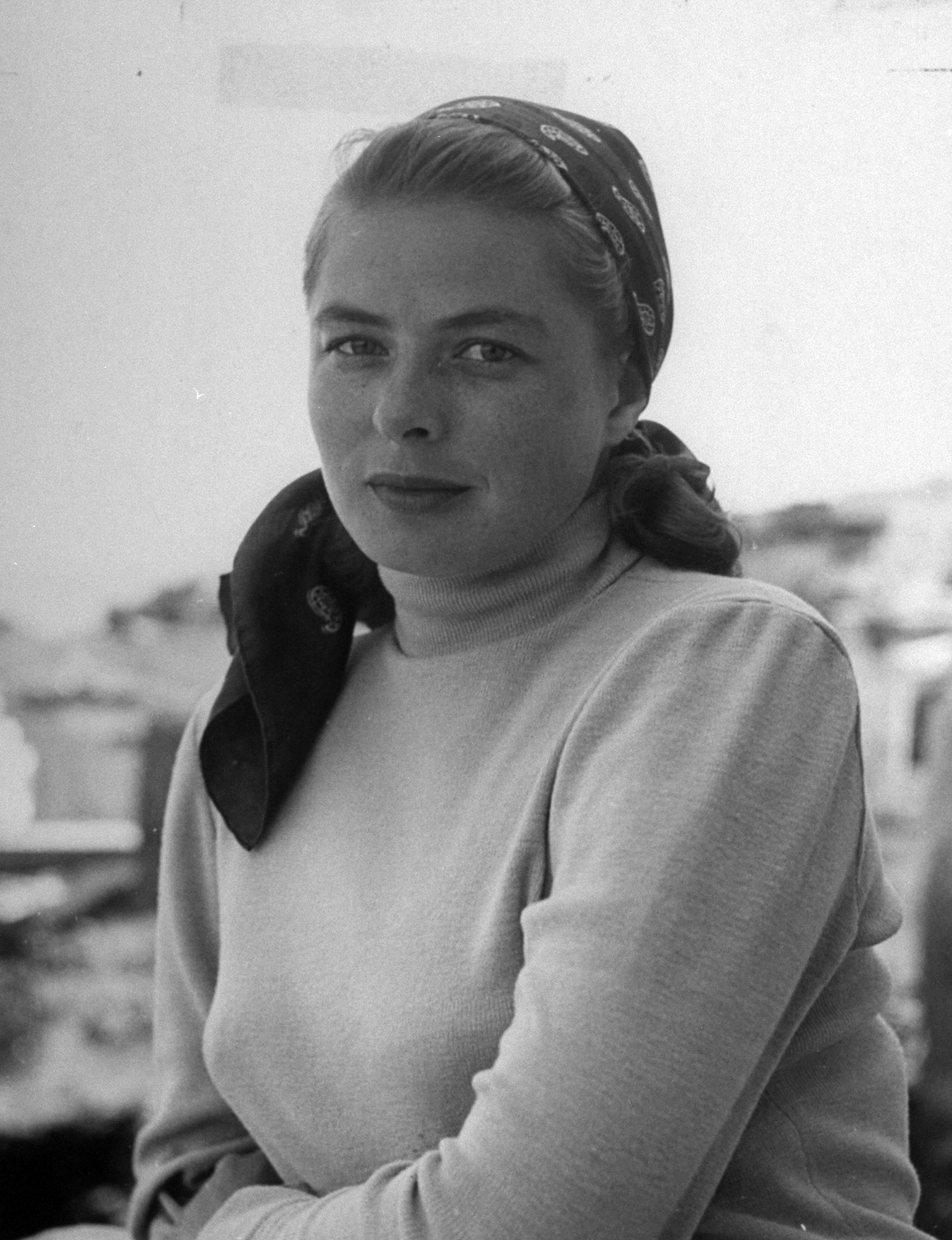

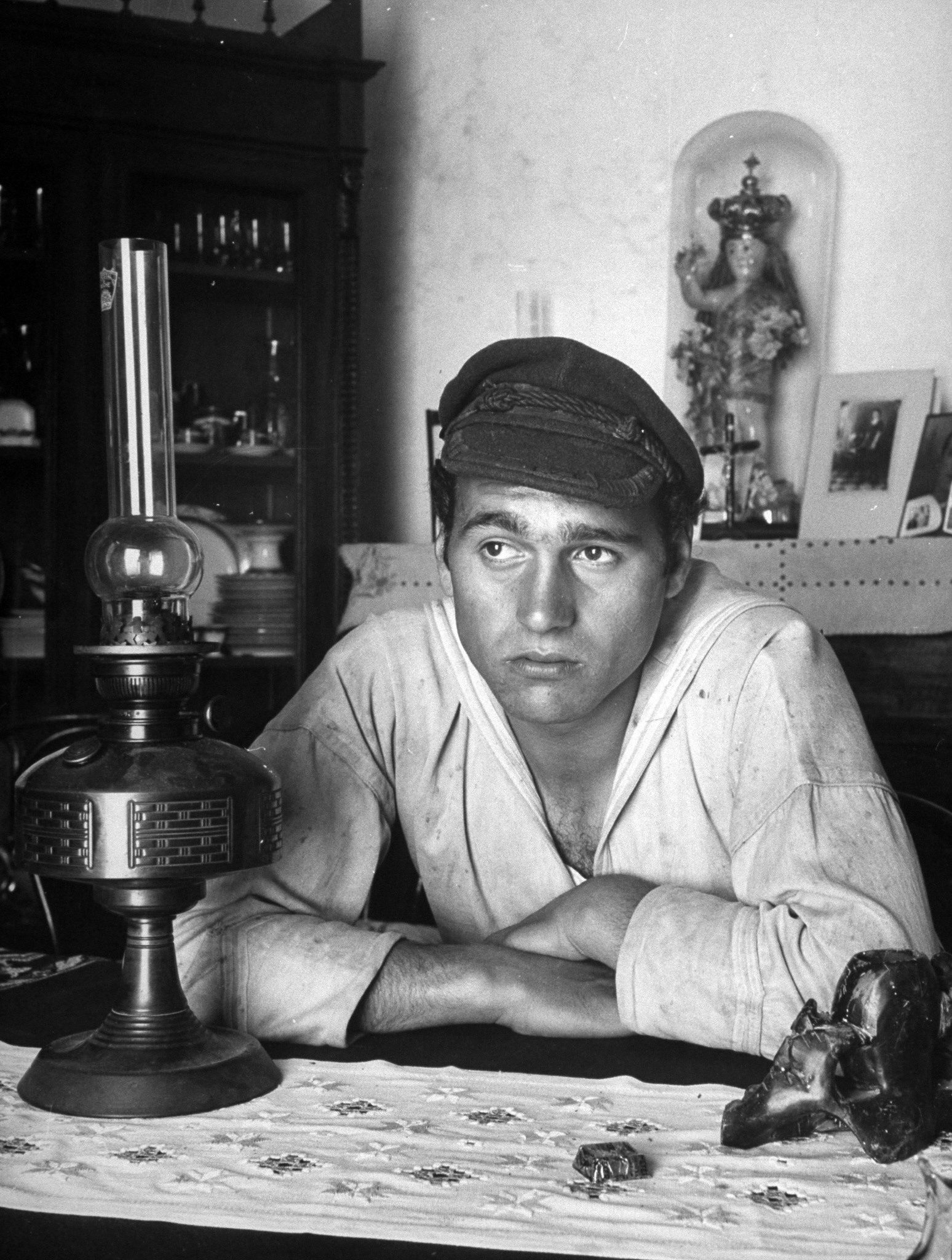

Parks and Sermolino spent two weeks on Stromboli, eventually winning Rossellini’s trust as well as Bergman’s. Parks photographed the movie’s cast and crew on the set and during the actual shooting. He made portraits of Bergman and her co-star, Mario Vitale. An unposed photograph of Rossellini and Bergman in a small boat on a dark day captures the emotional strain that both were under. (That strain would soon lift, as the pair would marry the following year and have three children together, including the actress Isabella Rossellini, before divorcing in 1957.)

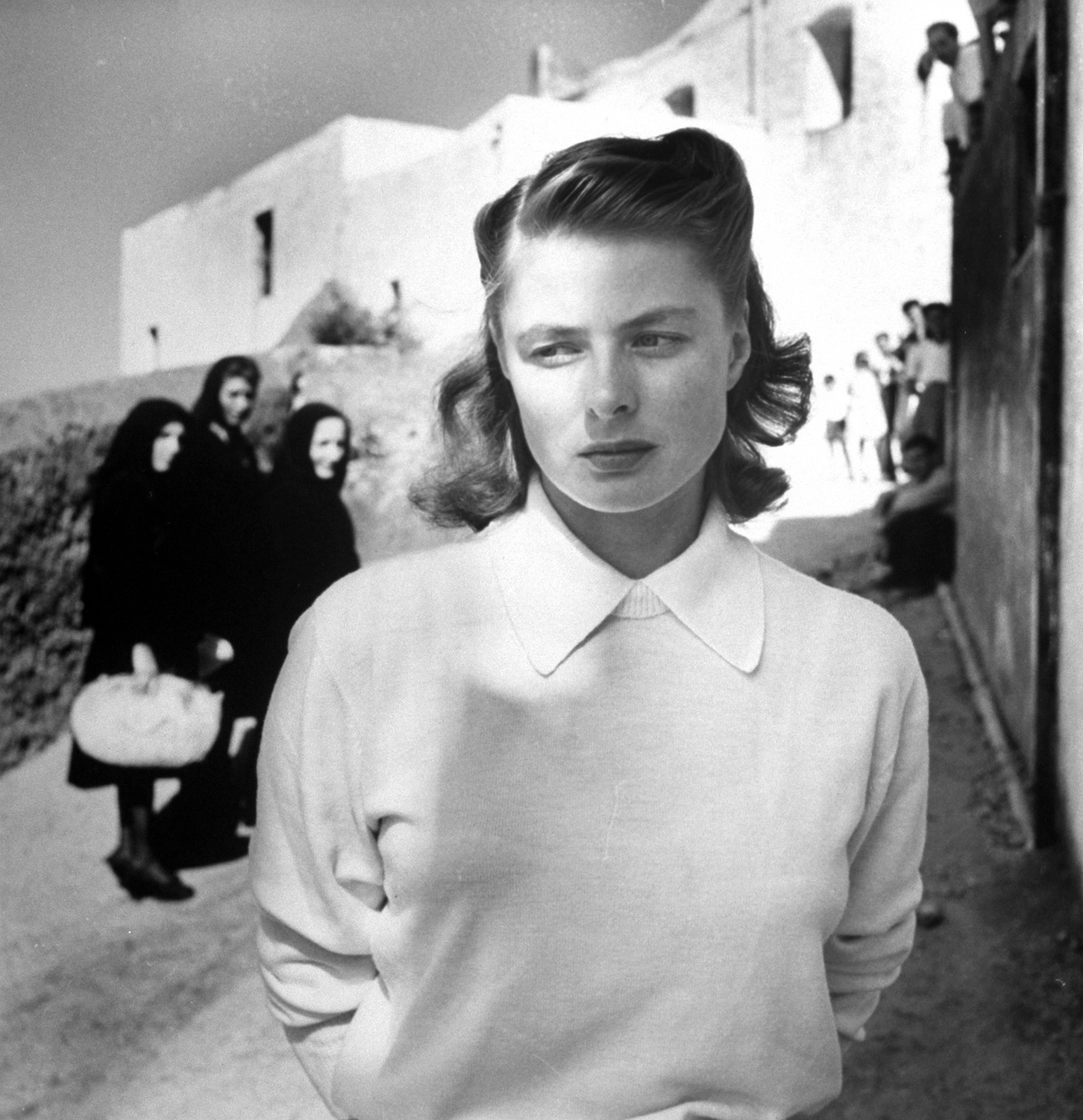

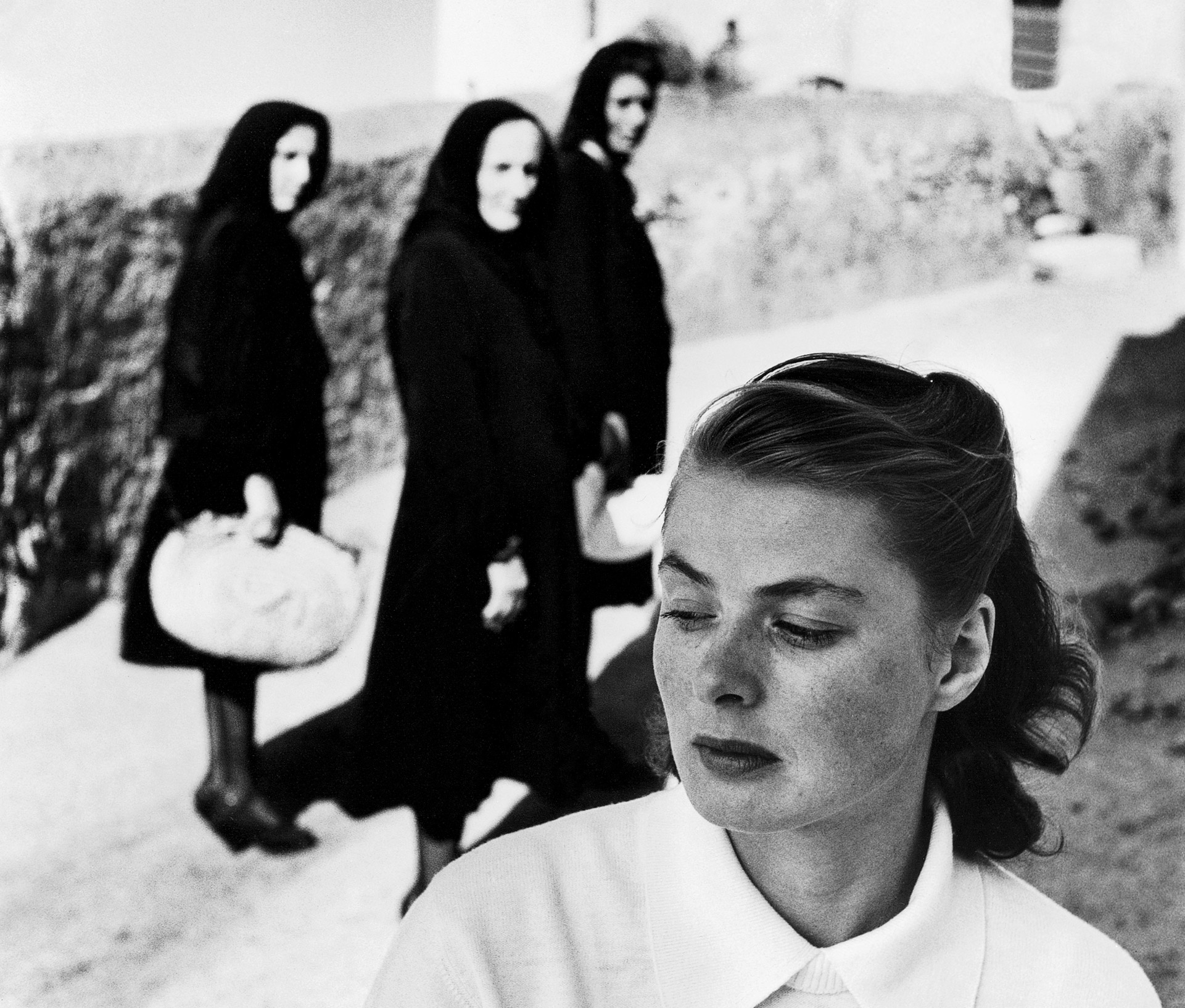

The most remarkable photographs that Parks made on Stromboli are two slightly different portraits of Bergman in a distant part of the island. As he was photographing her, he writes in A Hungry Heart, the last of his memoirs, “three women stopped on the hill above us. Clad in black, and resembling ominous birds, they stared at her with curiosity. Aware of their presence, Ingrid waited for them to leave. I allowed my camera to record this sardonic moment.”

Despite their range and emotional power, LIFE chose not to use any of Parks’ photographs in the story that it ran on Rossellini and Bergman’s affair. But Parks published and exhibited the two photographs of Bergman and the three women in black throughout his lifetime. In one, Parks emphasizes Bergman’s vulnerability; in the other, she seems more knowing. Both seem to reveal a rare intimacy between the photographer and the subject, and in the decades since he made them, they have become two of his most iconic images.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com