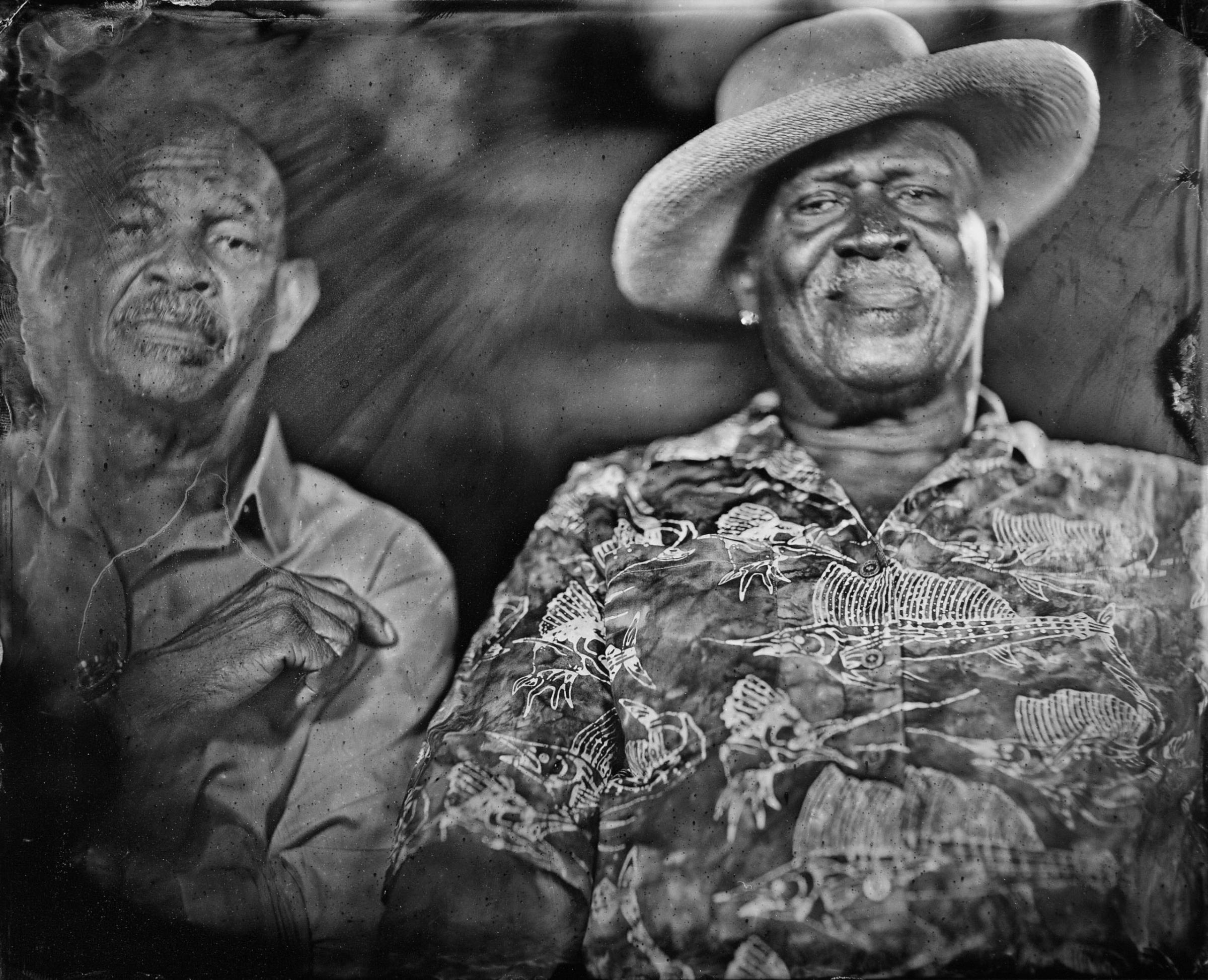

Ironing Board Sam began playing the pump organ as a small child in Rock Hill, South Carolina. By 14, he was playing local gigs for 10 bucks a pop. By 16, he was entertaining revelers at Winston-Salem drink-houses with his boogie-woogie piano tunes. By the mid-1960s, he’d landed a regular gig playing on Night Train, the first African-American TV music program. He played with a still-unknown Jimi Hendrix and the already wildly popular Sam Cooke.

But 50 years later, he found himself struggling to make ends meet, especially after Hurricane Katrina ravaged his adopted home of New Orleans. Enter the Music Maker Relief Foundation, a nonprofit that supports older blues musicians in everything from financial assistance to career development. Tim Duffy, Music Maker’s founder and executive director, tells TIME that since partnering with the foundation, Sam’s life has turned around. “We get him glasses, a car, a place to live, performing clothes, a keyboard. That was four years ago, now he’s on his fourth record, he has a new record coming out and he played the Newport Folk Festival.”

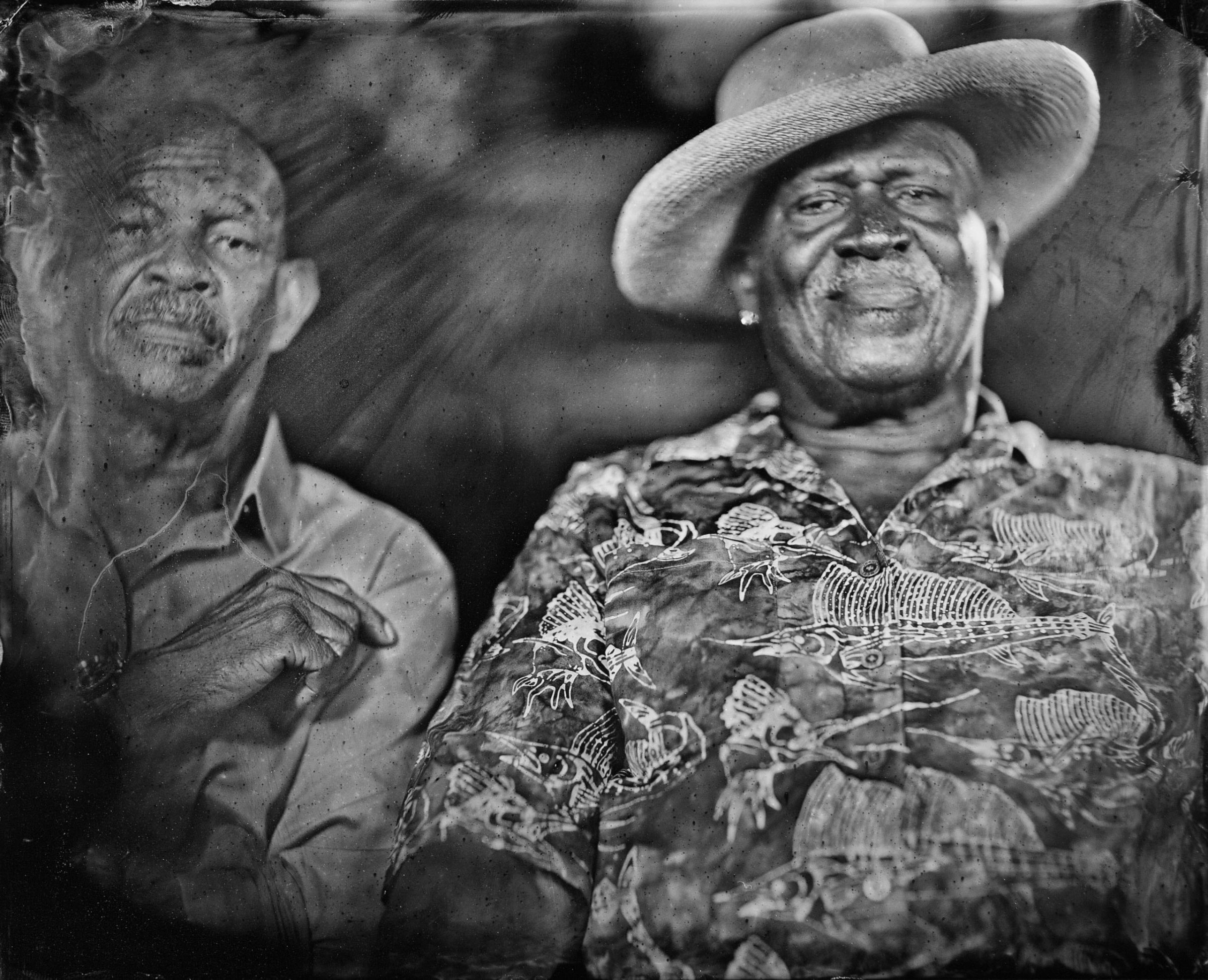

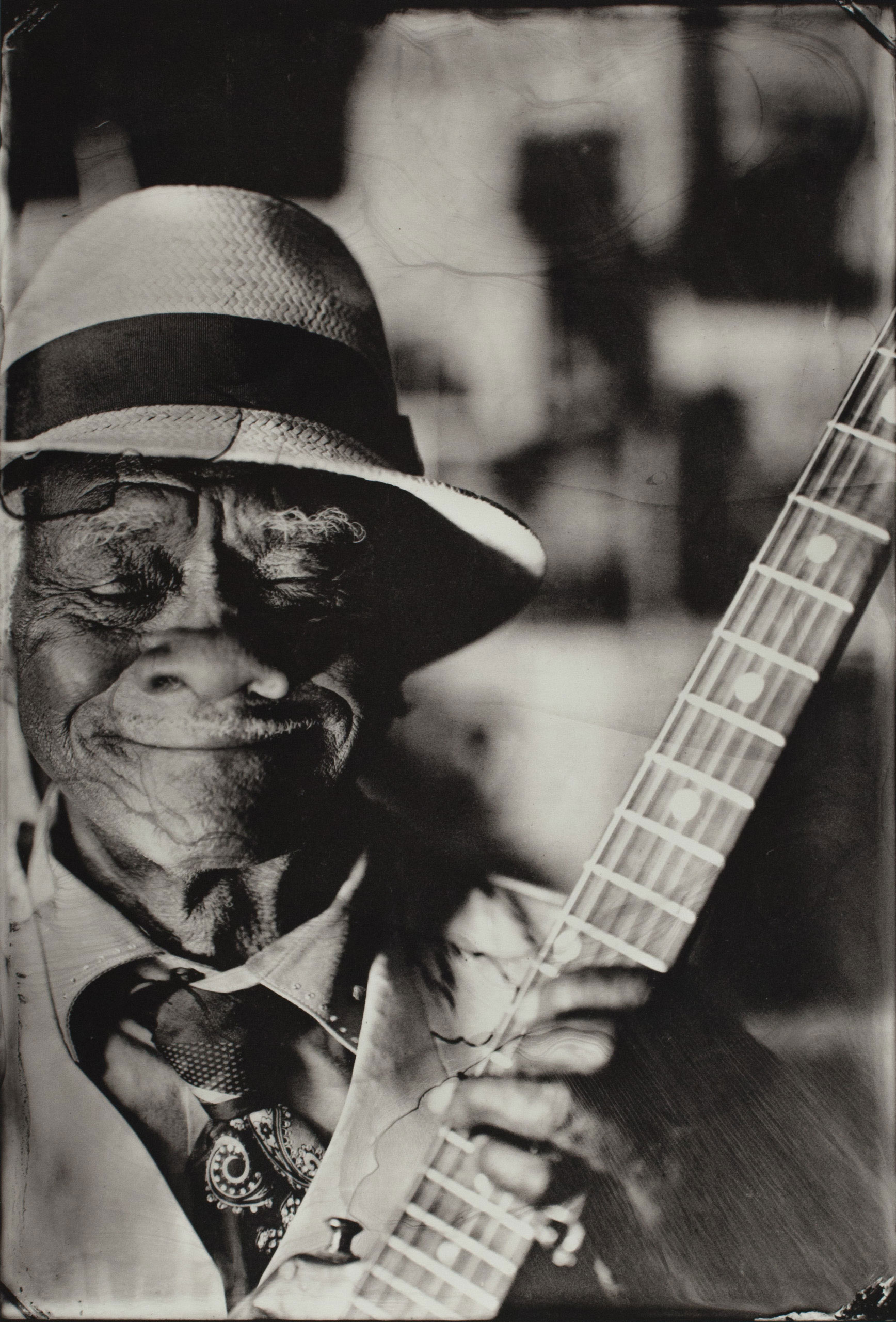

Sam is one of more than 300 artists Music Maker has supported since 1994, and in that time, Duffy has expanded his already long list of titles—scholar of folklore, record producer, fierce supporter of the blues—to include another: photographer. As he set out to record and catalog the work of Southern blues and gospel artists, many of whom were virtually unheard of, Duffy began photographing them. Somewhere along the way, he became an artist.

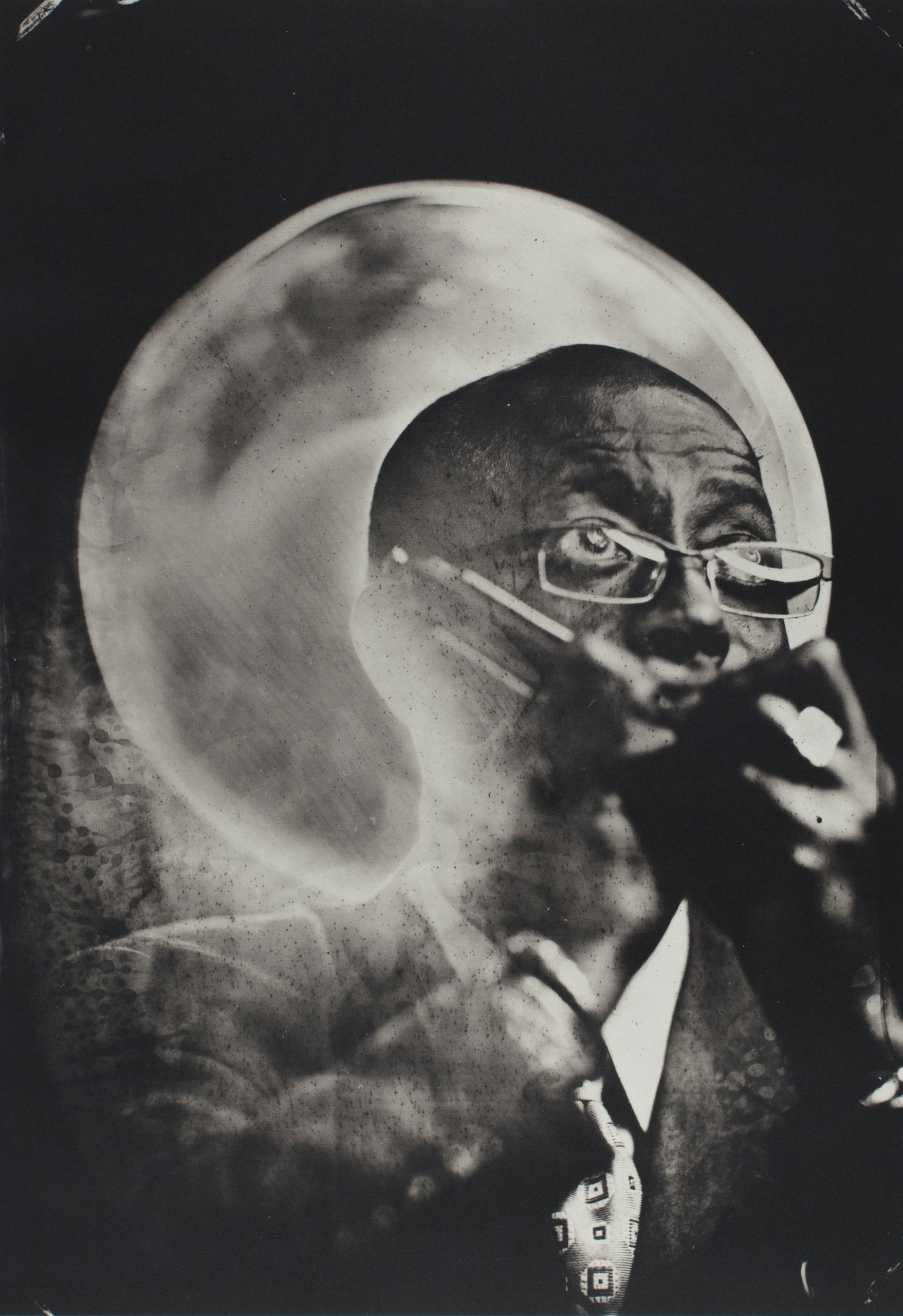

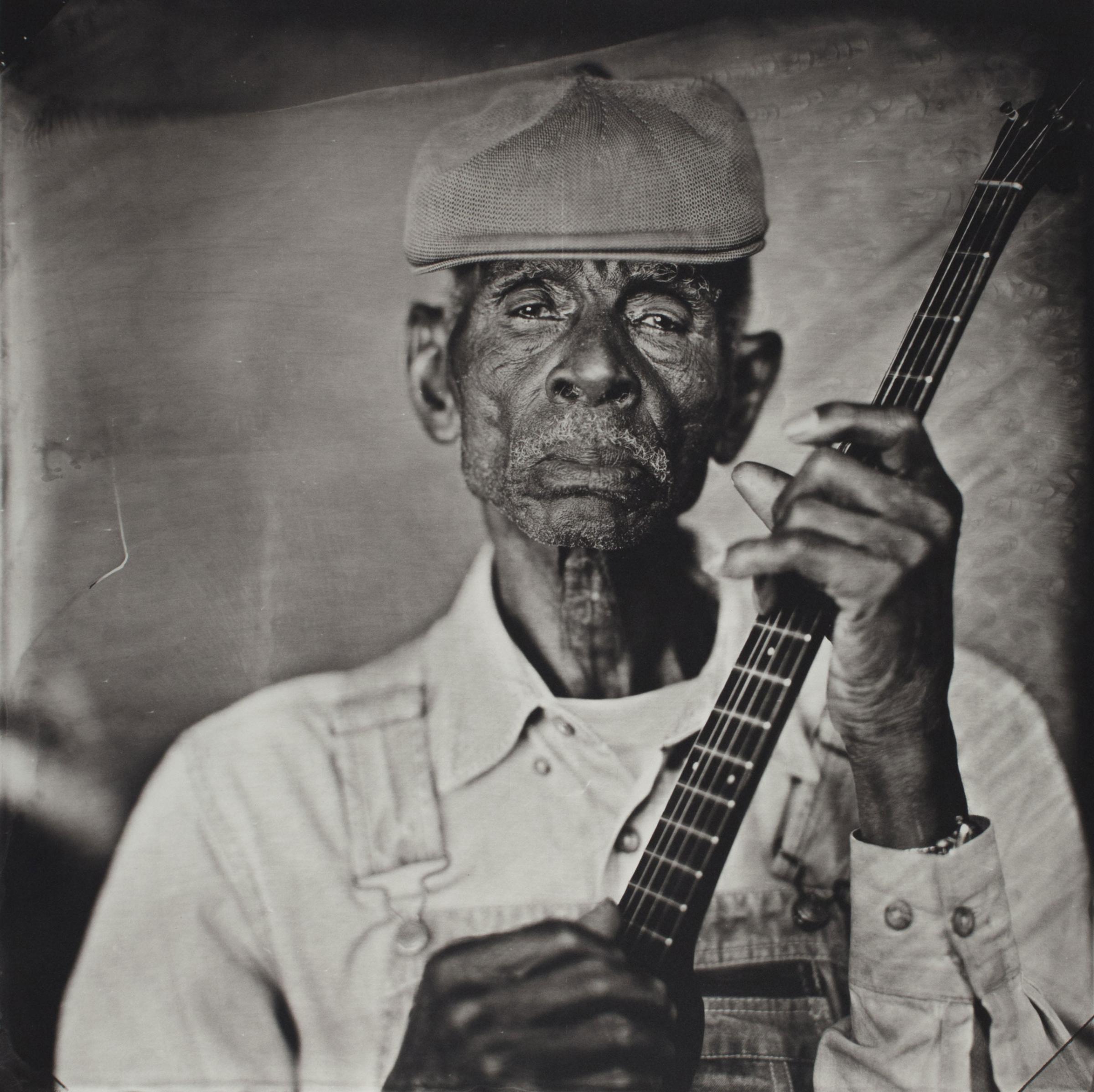

When Duffy was working on his graduate degree in folklore, he recounts, “a lot of people were saying that the blues was dead. But it didn’t make sense to me because I was meeting great blues artists that were born in the early 1900s.” Nurturing a lifelong interest in the medium, Duffy began photographing the artists with whom his foundation worked. He experimented with large format cameras and eventually became interested in wet-plate collodion, a photographic process dating back to the 1860s, in which an image is exposed directly onto a thin piece of metal treated with a collodion emulsion solution.

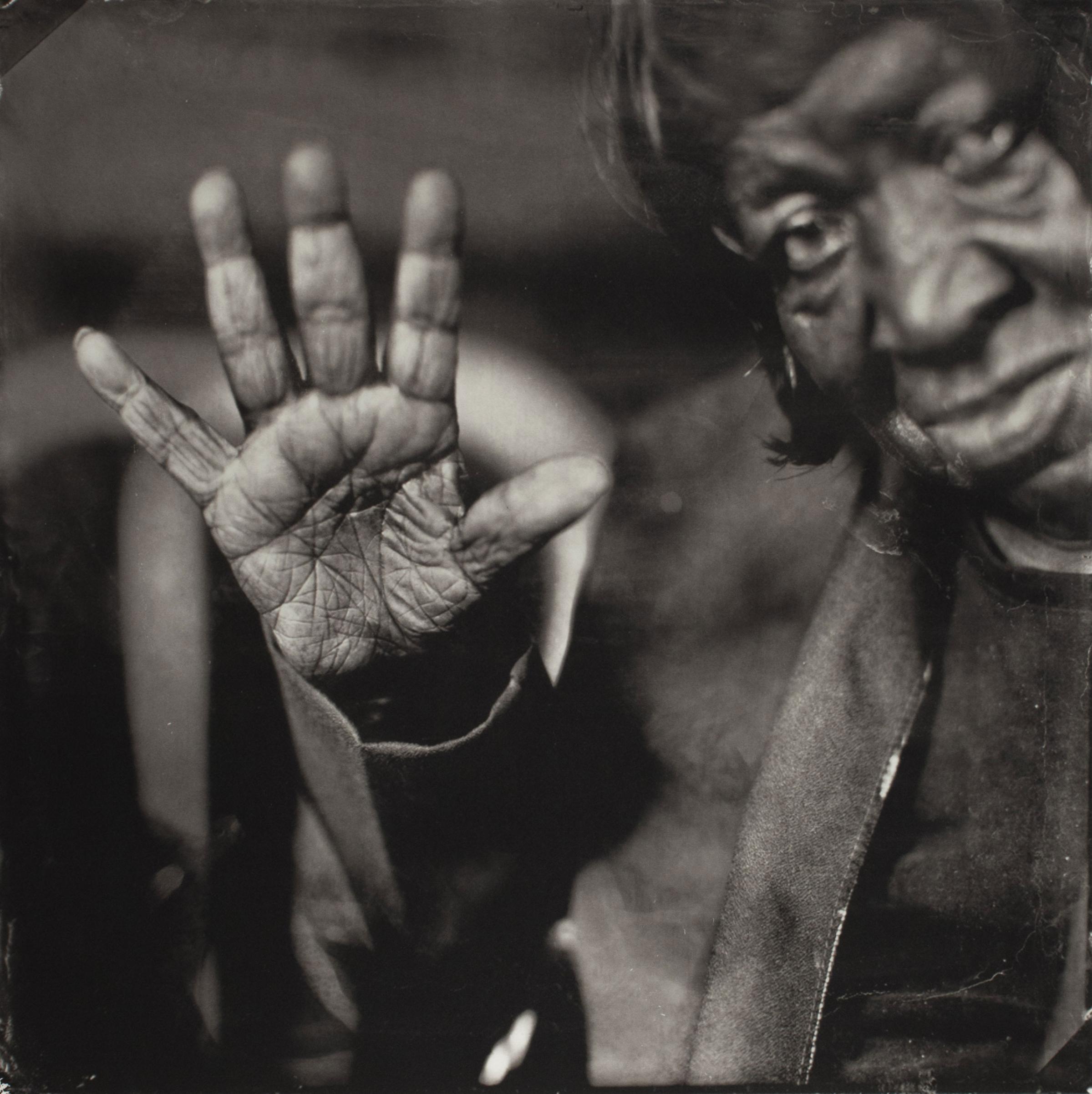

Tintypes require a decidedly more involved process than the digital photographs Duffy was accustomed to making. But they appealed to him because of their longevity. He had more than 100,000 digital images languishing, unseen, on hard drives at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “I kept looking at these tintypes. I’d see them at flea markets, and they’ve been around for probably 100 years,” he says. “And I thought, this is probably the most stable way I could preserve these guys.”

Indeed, Duffy’s images have a timeless quality. One has to look hard for clues that bely their vintage appearance, if any are to be found at all. The lengthy process of making a tintype means Duffy might work all day for just four or five shots, greatly increasing the level of attention devoted to each one. And sometimes the work benefits from happy accidents—like the time he returned to a plate sitting in water to find that birds had turned it into a birdbath, leaving trails of tiny triangle footprints.

Because there is no photographic negative with tintypes—the tintype itself is the source material—Duffy was, until recently, limited in his ability to exhibit the work. But a chance meeting with Steven Albahari, the publisher of literary art bookmakers 21st Editions, led to a partnership that will allow the images not only to be duplicated, but to be printed in an unusually beautiful photographic process. 21st Editions specializes in platinum palladium printing, a process that dates back to the early 1880s and which Albahari calls “the Cadillac of the photograph.”

Though the transformation from tintype to platinum palladium is less pronounced on a screen, the distinction in person is palpable. (The images in the gallery above are from platinum palladium prints, whereas the image below is from one of Duffy’s original tintypes.) Because the platinum palladium process allows for one of the broadest tonal ranges in photographic printing, the end result seems to glow, its subject almost jarringly proximate. The ink becomes ingrained in the paper, rather than sitting on top of it, allowing for a depth uncharacteristic of the medium.

The partnership will allow Duffy to exhibit his work in multiple settings simultaneously, beginning with a show, “Our Living Past: A Platinum Portrait of Music Maker,” at the Atlanta International Airport in November, followed by exhibits in Florida and Kentucky throughout 2016 and 2017.

Taj Mahal, a Grammy-winning blues musician who has known Duffy for more than two decades and recently posed for a tintype, credits Duffy’s work not just for its rich aesthetic quality, but for his genuine respect and affection for his subjects. “So many photographs of older bluesmen or African-Americans are more voyeuristic, as opposed to the energy of the people—what they do, what it is they’re into—coming across in the photograph,” he tells TIME. But Duffy “never treads on people’s dignity.”

Duffy hopes his images will provide a counter-narrative to the way in which blues musicians are often discussed. “The way the music business works, we strip everything away from the creators and leave them with no money, and everyone else makes money. Then the academics will come in and say, it’s all gone, there’s nothing left,” he says. “But you live in the South like I have for the last 25, 30 years, and this music is held dear and cherished by the communities it was born from. Everyone thinks it’s gone, but they’re still here.”

Eliza Berman is an Associate Editor at TIME and LIFE.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com