The news that Legionnaires’ disease has killed a dozen New Yorkers this summer—and that an inmate at Rikers Island has been diagnosed as well—has put the illness in the headlines and hospitals. Luckily, these days, most people who experience symptoms can be treated successfully with antibiotics.

But that wasn’t the case when the disease was first discovered. Not only did Legionnaires’ prove fatal to many affected by its first notable outbreak, but those victims didn’t even know what was making them sick.

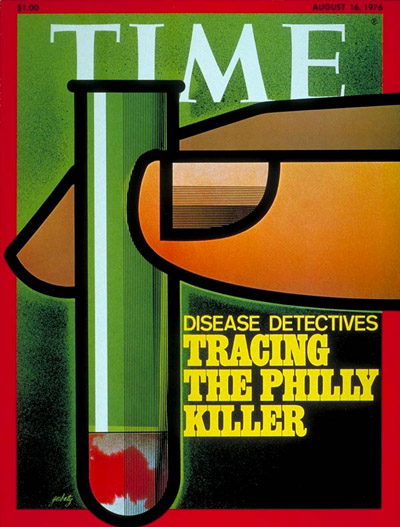

The legionnaires after whom the disease is named were attendees at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in July of 1976. They were veterans like Ray Brennan, Frank Aveni and Charles Seidel, who went to an ordinary meeting, fell ill shortly after with chest pains and high fevers, and died not long after. They had spent time all over the city, eaten in restaurants and traveled home in a variety of ways. In a cover story that August about the “disease detectives” who were trying to find “the Philly killer,” TIME captured the panic that resulted from the outbreak. The magazine noted many friends and neighbors of John Bryant Ralph, another Legionnaire, did not attend his funeral for fear his disease might be catching.

For many Americans, the Philadelphia outbreak was the first time they were aware of the work done by the Centers for Disease Control, a then-obscure organization that went to work trying to figure out what was killing the Legionnaires:

Like police work, most medical sleuthing is done in the field by the “shoe leather” epidemiologists, some from the state’s public health service, others from the CDC. They crisscrossed the state to interrogate every one of the stricken Legionnaires and the families and friends of the deceased. Their quest: a common denominator, a set of experiences that would link all the victims, such as meals taken together, rooms in the same hotel, exposure to similar contamination. Their method: careful questioning and cross-referencing.

“Hello, I’m part of the medical team investigating this weird disease,” said Dr. Stephen Thacker, 28, as he sat down beside Thomas Payne’s bed in Chambersburg Hospital. “How do you feel? When did you first feel sick? Where did you eat and stay in Philadelphia? When did you arrive there? When did you leave? Did you go to the testimonial dinner? Or the go-getter’s breakfast? Did you go to the hospitality rooms for the state commander or other officials? Did you have any contact with pigs?”

In some ways the detectives’ legwork raised more questions than it answered. A check of the hotels at which the conventiongoers had stayed revealed no outbreak of the mysterious illness among employees who had come in contact with the Legionnaires. The investigators could find no evidence that any of the victims had been exposed to pigs, which have been implicated as the animal reservoir for the swine-flu virus. Nor could the disease detectives explain another apparent contradiction: why some people developed the disease, while others, who ate the same meals, drank the same drinks or shared their rooms during the convention, did not.

The disease remained elusive. “There’s an outside chance we may never find out the cause,” CDC Director David Sencer told TIME. “I think we will. But there are times when disease baffles us all. It may be a sporadic, a onetime appearance.”

Eventually, the initial outbreak tapered off and, though nearly 200 had become ill and 29 had died, fear tapered off too. It was clear that whatever it was, it wasn’t spreading—but, though public interest waned, the CDC kept working. It wasn’t until months later that the mystery was actually solved.

“Five months after the convention, [CDC microbiologist Joseph McCade] took another look at some red sausage-shaped bacteria and concluded that they were the culprits,” TIME later explained, in a 1983 cover story about the CDC. “They had festered in the water of the hotel’s cooling tower and had been carried through the air as the water evaporated.”

Read the 1976 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: Tracing the Philly Killer

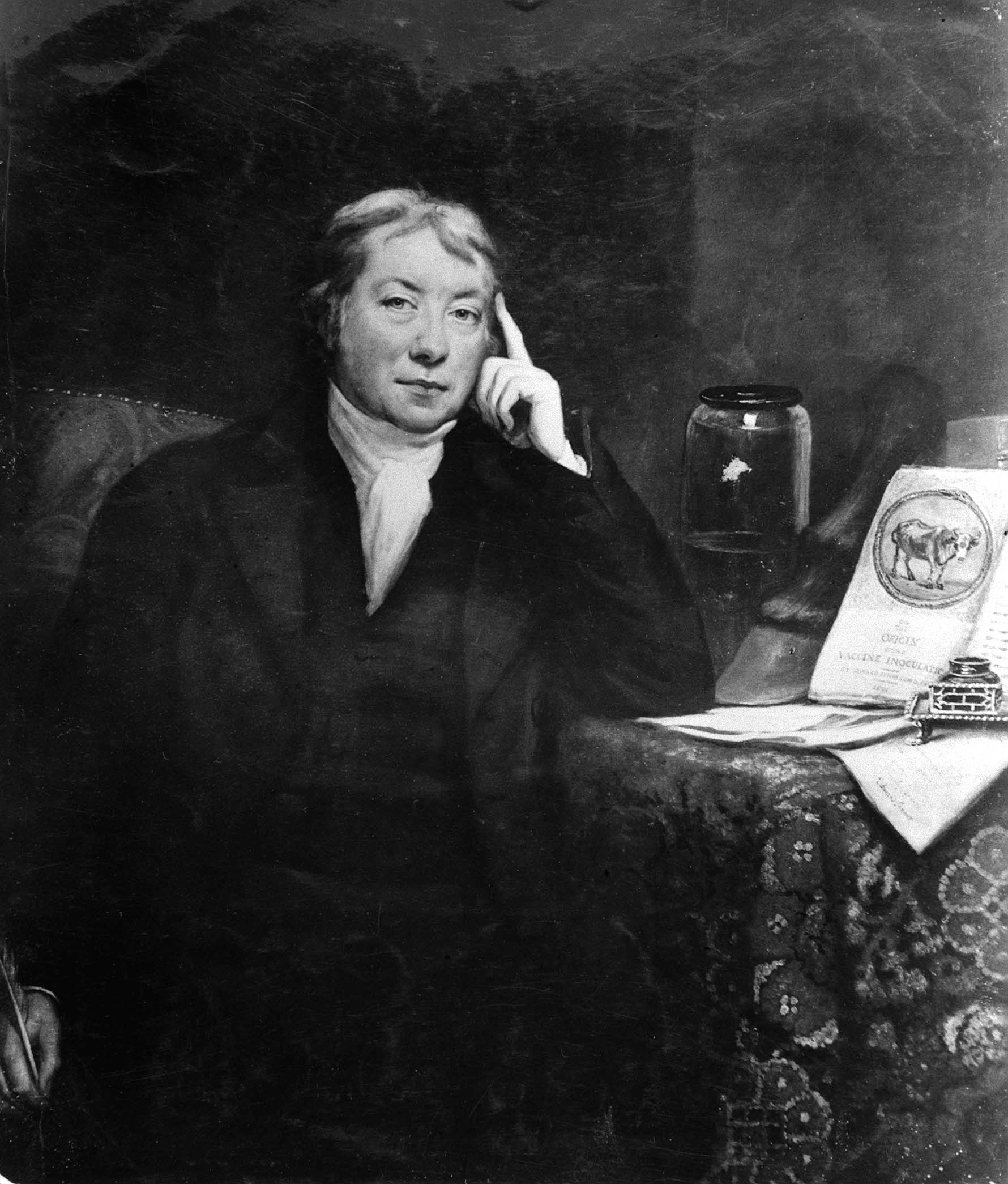

Edward Jenner

No one knows the name of the dairy maid 13-year old Edward Jenner overheard speaking in Sodbury, England in 1762, but everyone knows what she said: “I shall never have smallpox for I have had cowpox. I shall never have an ugly pockmarked face.” Jenner was already a student of medicine at the time, apprenticed to a country surgeon, and the remark stayed with him. But it was not until 34 years later, in 1796, that he first tried to act on the dairy maid’s wisdom, vaccinating an 8-year-old boy with a small sample from another dairy maid’s cowpox lesion, and two months later exposing the same boy to smallpox. The experiment was unethical by almost any standard—except perhaps the standards of its time—but it worked. Jenner became the creator of the world’s first vaccine, and 184 years later, in 1980, smallpox became the first—and so far only—disease to have been vaccinated out of existence.

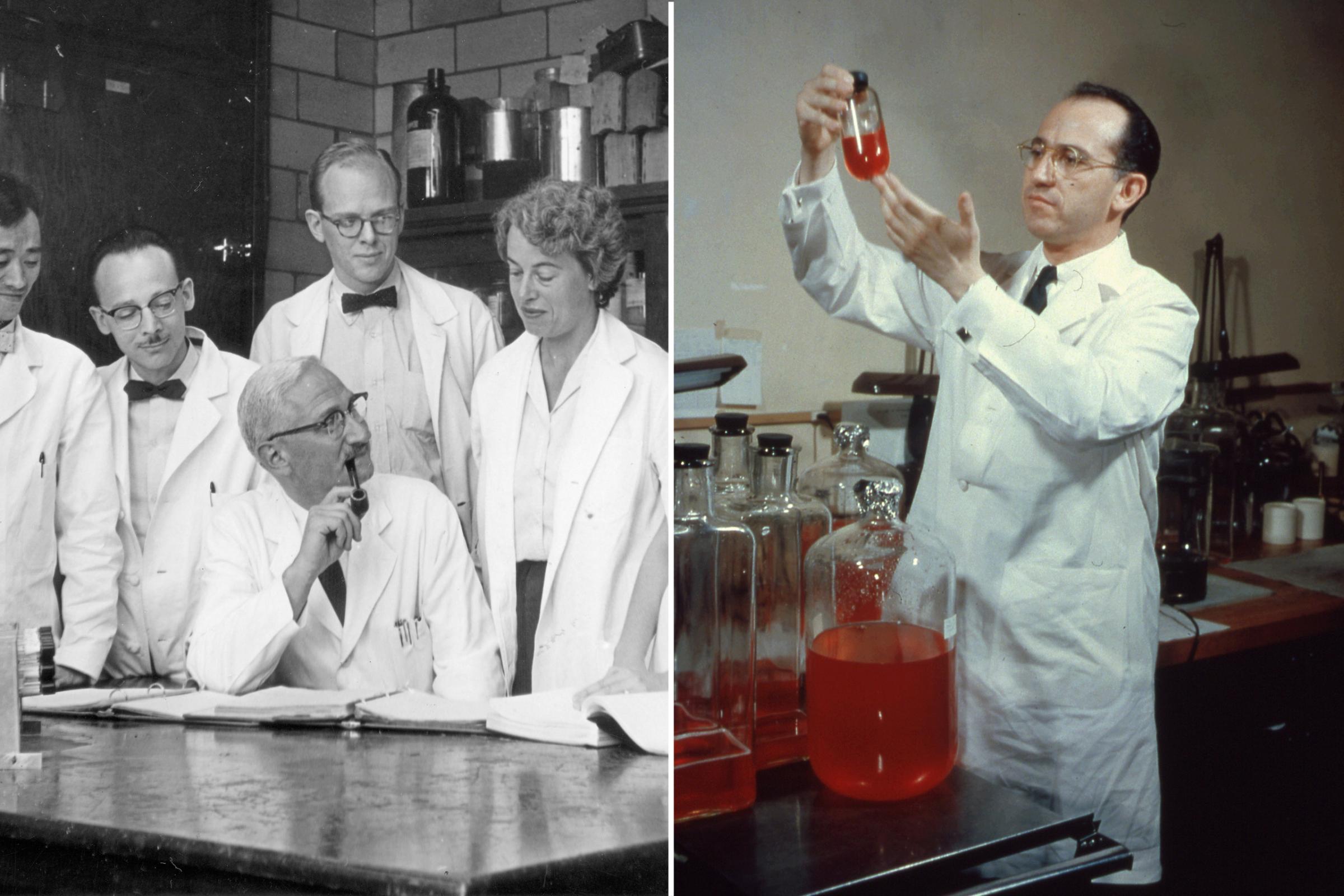

Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin

Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin didn’t much care for each other. The older, arid Sabin and the younger, eager Salk would never have been good matches no matter what, but their differences in temperament were nothing compared to a disagreement they had over science. Both researchers were part of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis—later dubbed the March of Dimes—and both were trying to develop a polio vaccine. Sabin was convinced that only a live, weakened virus could do the trick; Salk was convinced a newer approach—using the remains of a killed virus—would be better and safer. Both men turned out to be right. Salk’s vaccine was proven successful in 1955; Sabin’s—which was easier to administer, especially in the developing world, but can cause the rare case of vaccine-induced polio due to viral mutations—followed in 1962. Both vaccines have pushed polio to the brink of eradication. It is now endemic in only three countries—Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria—and appears, at last, destined to follow smallpox over the extinction cliff.

Dr. Maurice Hilleman

Around the world, untold numbers of children owe their health to a single girl who woke up sick with mumps in the early morning hours of March 21, 1963. The girl was Jeryl Lynne Hilleman, who was then only 5; her father was a Merck pharmaceuticals scientist with an enduring interest in vaccines. Dr. Maurice Hilleman did what he could to comfort his daughter, knowing the disease would run its course; but he also bristled at the fact that a virus could have its way with his child. So he collected a saliva sample from the back of her throat, stored it in his office, and used it to begin his work on a mumps vaccine. He succeeded at that—and a whole lot more. Over the course of the next 15 years, Hilleman worked not only on protecting children against mumps, but also on refining existing measles and rubella vaccines and combining them into the three-in-one MMR shot that now routinely immunizes children against a trio of illnesses in one go. In the 21st century alone, the MMR has been administered to 1 billion children worldwide—not a bad outcome from a single case of a sickly girl.

Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering

It was not easy to be a woman in the sciences in the 1930s, something that Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering knew well. Specialists in public health—one of the only scientific fields open to women at the time—they were employed by the Michigan Department of Health, working on the routine business of sampling milk and water supplies for safety. But in their free time they worried about pertussis—or whooping cough. The disease was, at the time, killing 6,000 children per year and sickening many, many more. The poor were the most susceptible—and in 1932, the third year of the Great Depression, there were plenty of poor people to go around. A pertussis vaccine did exist, but it was not a terribly effective one. Kendrick and Eldering set out to develop a better one, collecting pertussis samples from patients on “cough plates,” and researching how to incorporate the virus into a vaccine that would provide more robust immunity. They tested their vaccine first on mice, then on themselves and finally, in 1934, on 734 children. Of those, only four contracted whooping cough that year. Of the 880 unvaccinated children in a control group, 45 got sick. Within 15 years of the development of Kendrick and Eldering’s vaccine, the pertussis rate in the U.S. dropped by 75%. By 1960 it was 95%—and has continued to fall.

Dr. Richard Pan

The work that’s done at the lab bench is not the only thing that makes vaccines possible; the work that’s done by policymakers matters a lot too. That is especially true in the case of California State Senator Richard Pan, a pediatrician by training who represents Sacramento and the surrounding communities. Pan was the lead sponsor of the recently enacted Senate Bill 277, designed to raise California’s falling vaccine rate by eliminating the religious and personal belief exemptions that many parents use to sidestep the responsibility for vaccinating their children. For Pan’s troubles, he now faces a possible recall election, with anti-vaccine activists trying to collect a needed 35,926 signatures by Dec. 31 to put the matter before the district’s voters. Pan is taking the danger of losing his Senate seat with equanimity—and counting on the people who elected him in the first place to keep him on the job. “I ran to be sure we keep our communities safe and healthy,” he told the Sacramento Bee. That is, at once, both a very simple and very ambitious goal, made all the harder by parents who ought to know better.

Dr. Andrew Wakefield

Not every conspiracy theory has a bad guy. No one knows the name of the founding kooks who got the rumor started that the moon landings were faked or President Obama was born on a distant planet. But when it comes to the know-nothing tales that vaccines are dangerous, there’s one big bad guy—Andrew Wakefield, the U.K. doctor who in 1998 published a fraudulent study in The Lancet alleging that the MMR vaccine causes autism. The reaction from frightened parents was predictable, and vaccination rates began to fall, even as scientific authorities insisted that Wakefield was just plain wrong. In 2010, the Lancet retracted the study and Wakefield was stripped of his privilege to practice medicine in the U.K. But the damage was done and the rumors go on—and Wakefield, alas, remains unapologetic.

Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey

If you’re looking for solid medical advice, you probably want to avoid getting it from a former Playboy model and talk show host, and a man who, in 1994’s Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, introduced the world to the comic stylings of his talking buttocks. But all the same, Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey are best known these days as the anti-vaccine community’s most high-profile scaremongers, doing even the disgraced Andrew Wakefield one better by alleging that vaccines cause a whole range of other ills beyond just autism. None of this is true, all of it is shameful, and unlike Wakefield, who was stripped of his medical privileges, Carry and McCarthy can’t have their megaphones revoked.

Rob Schneider

What’s that you say? Need one more expert beyond Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey to weigh in on vaccines? How about Rob Schneider, the Saturday Night Live alum and star of the Deuce Bigalow, Male Gigolo films? Schneider has claimed that the effectiveness of vaccines has “not been proven,” that “We’re having more and more autism” as a result of vaccinations, and that mandating vaccines for kids attending public schools is “against the Nuremberg laws.” So, um, that’s all wrong. A vocal opponent of the new California law eliminating the religious and personal belief exemptions that allowed parents to opt out of vaccinating their kids, Schneider called the office of state legislator Lorena Gonzalez and left what Gonzalez described as a “disturbing message” with her staff, threatening to raise money against her in the coming election because of her support of the law. Gonzalez called him back and conceded that he was much more polite in person. Still, she wrote on her Facebook page, “that is 20 mins of my life I’ll never get back arguing that vaccines don’t cause autism with Deuce Bigalow, male gigolo.#vaccinateyourkids.”

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

If you’re looking for proof that smarts can skip a generation, look no further that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., son of the late Bobby Kennedy. RFK Jr. has made something of a cottage industry out of warning people of the imagined dangers of thimerosal in vaccines. An organomercury compound, thimerosal is used as a preservative, and has been removed from all but the flu vaccine—principally because of the entirely untrue rumors that it causes brain damage. But facts haven’t silenced Kennedy who, as a child of the 1950s and ‘60s, surely got all of the vaccines his family doctor recommended. Children of parents who listen to what he has to say now will not be so fortunate.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com