This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at HistoryToday.com.

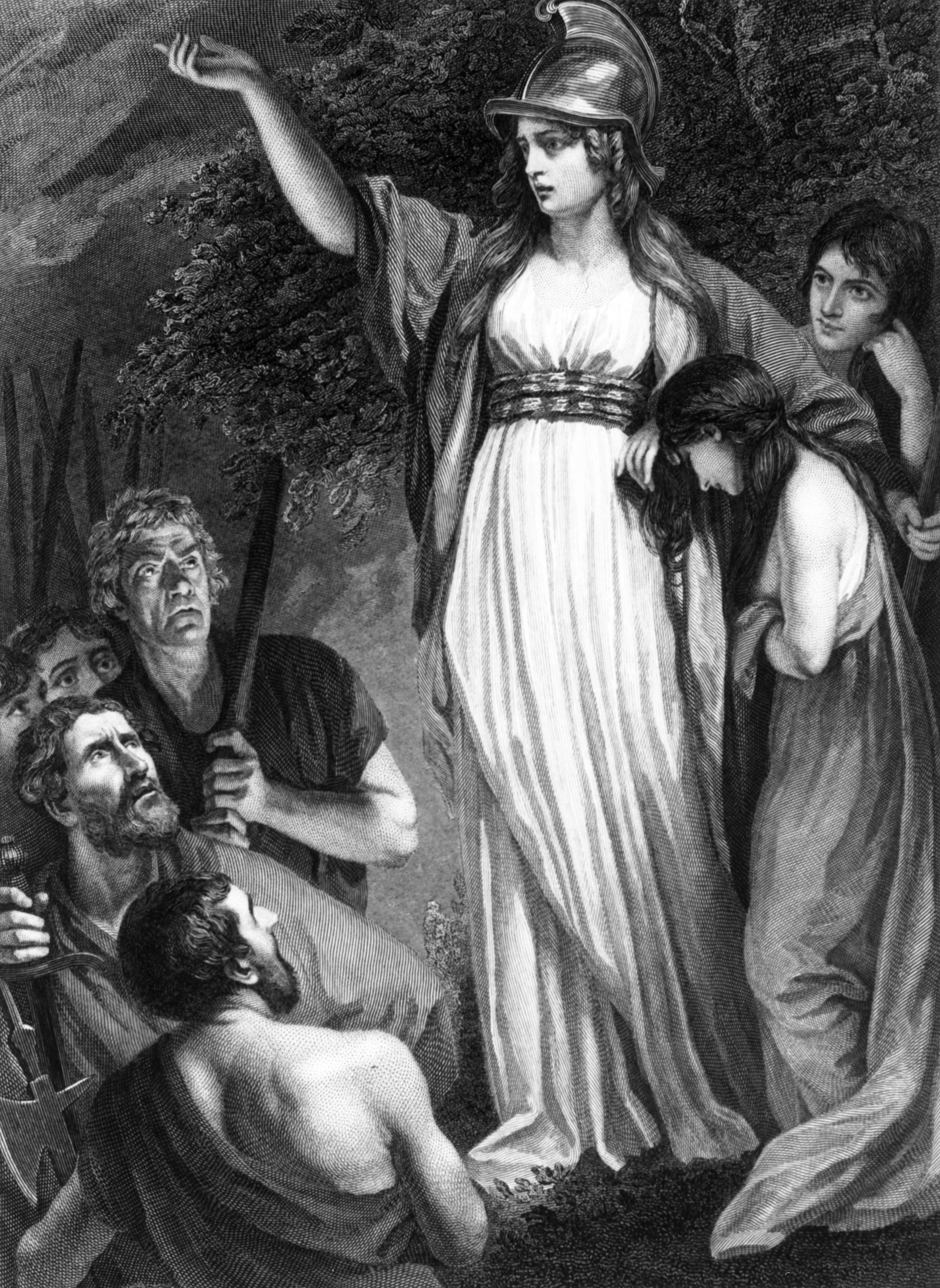

The summer of 1643 saw the political unrest that had culminated in the beginning of the English Civil Wars the previous year spill into the streets of Westminster. Between August 7th and 9th there were a series of pro- and anti-war demonstrations in the capital. In a letter to his wife, Katherine, dated August 9th that year, the monarchist Thomas Knyvett reported how the House of Lords had sent a number of ‘very honourable’ proposals to reopen talks for a peace treaty with Charles I to the Commons. The proposals were thrown out by a small majority. Knyvett was dismayed at the Commons’ rejection, signing his letter ‘thy poor disconsolate husband T. K.’ A group of women had clearly taken the same view and on Tuesday August 8th had gathered outside the Houses of Parliament to protest for peace. The women, described by Knyvett as a ‘multitude’, several hundred strong, were apparently given some verbal reassurances and dispersed without incident.

However, the next day the women returned to Westminster in much greater numbers with the intention of meeting with Parliamentary leaders, such as John Pym, to present them formally with ‘The Petition of Many Civilly Disposed Women.’ The organized nature of the protest was clear, as all the women were supplied with white ribbons to wear in their hats as a symbol of the peace they sought. John Dillingham’s newspaper The Parliament Scout for the week beginning August 3rd claimed that 5-6,000 women were involved in this second day of action. He also wrote that a tenth of the women were prostitutes, but mostly they were poor women whose husbands were away in the army. Richard Colling’s newspaper, The Kingdom’s Weekly Intelligencer, went further and reported that the women were largely comprised of ‘whores, bawds, oyster-women, kitchen-stuff women, beggar women and the very scum of the suburbs, besides a number of Irish women.’ The idea that this was a random convergence of malcontented women goes against the organized nature of the protest and, in fact, some sources say that the ribbons were given out by a ‘Lady Brunchard.’ Around lunchtime the women heatedly blockaded the entrance to Parliament for two hours. The protest turned violent as Sir William Waller’s horse regiment attempted to suppress it. Knyvett told his wife in his next letter of August 10th that ‘there was much mischief done by the horse and foot soldiers.’ Two men were known to have been killed and numerous men and women injured.

Listening to news of the day’s events as they unfolded was John Norman, who ran a spectacle shop. From the prime position of his shop door just outside Westminster Gate, Norman could take in all that was happening. He was on the side of Parliament and had been heard to say that he would ‘rather see the streets run with blood than that we should now have peace.’ Amid the chaos, news spread that one of the women protestors had been shot dead in the nearby churchyard. Norman was unsympathetic, commenting that it did not matter to him if ‘a hundred of them were so served.’ Rushing out to see the commotion closer, Norman found that the woman who had been killed was his own daughter. The young woman, described by Knyvett as a ‘pretty young wench,’ worked as seamstress in Westminster Hall and was believed to have been accidentally shot when she crossed the Palace Yard while running an errand unconnected to the protest. The soldier who fired the shot was investigated, but apparently let off when his defense that his pistol went off accidentally was accepted.

The Intelligencer suggested that women in general should use the young woman’s death as a warning not to get caught up in such uprisings. The Parliament Scout blamed the death on the women themselves for uprising, claiming that ‘Tumults are dangerous, swords in the hands of women do desperate things; this is begotten in the distractions of Civil War.’ There is a twist in the story of the seamstress, however, and it is alluded to in the Intelligencer. The paper’s account of the incident mentions almost in passing that ‘the malignants say, it was done by a trooper that rid up to her, and shot her purposely, others say it went off by mischance,’ echoing the soldier’s own defense. The antiquarian and parliamentarian MP Sir Simonds D’Ewes noted in his journal that the horse soldier who shot the woman was a ‘profane fellow’ who bore an old grudge against the spectacle-seller and so used the opportunity to ‘shoot his daughter to death as she was peaceably going upon an errand.’ We do not know if the seamstress was unwittingly caught in the riot, or if she had decided to join in the unrest; nor if she was a victim of a tragic accident or an opportunistic murder. For Thomas Knyvett, it was an opportunity to spread propaganda about the other side, as a man who had been heard to claim that he would rather see the streets running with blood than accept a compromise with the king had seen his own daughter’s blood shed in the street. Knyvett instructed his wife to be bold and tell this story widely because it was ‘certainly true.’

Sara Read is the author of Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Women’s Lives, 1540-1740 (Pen & Sword, 2015).

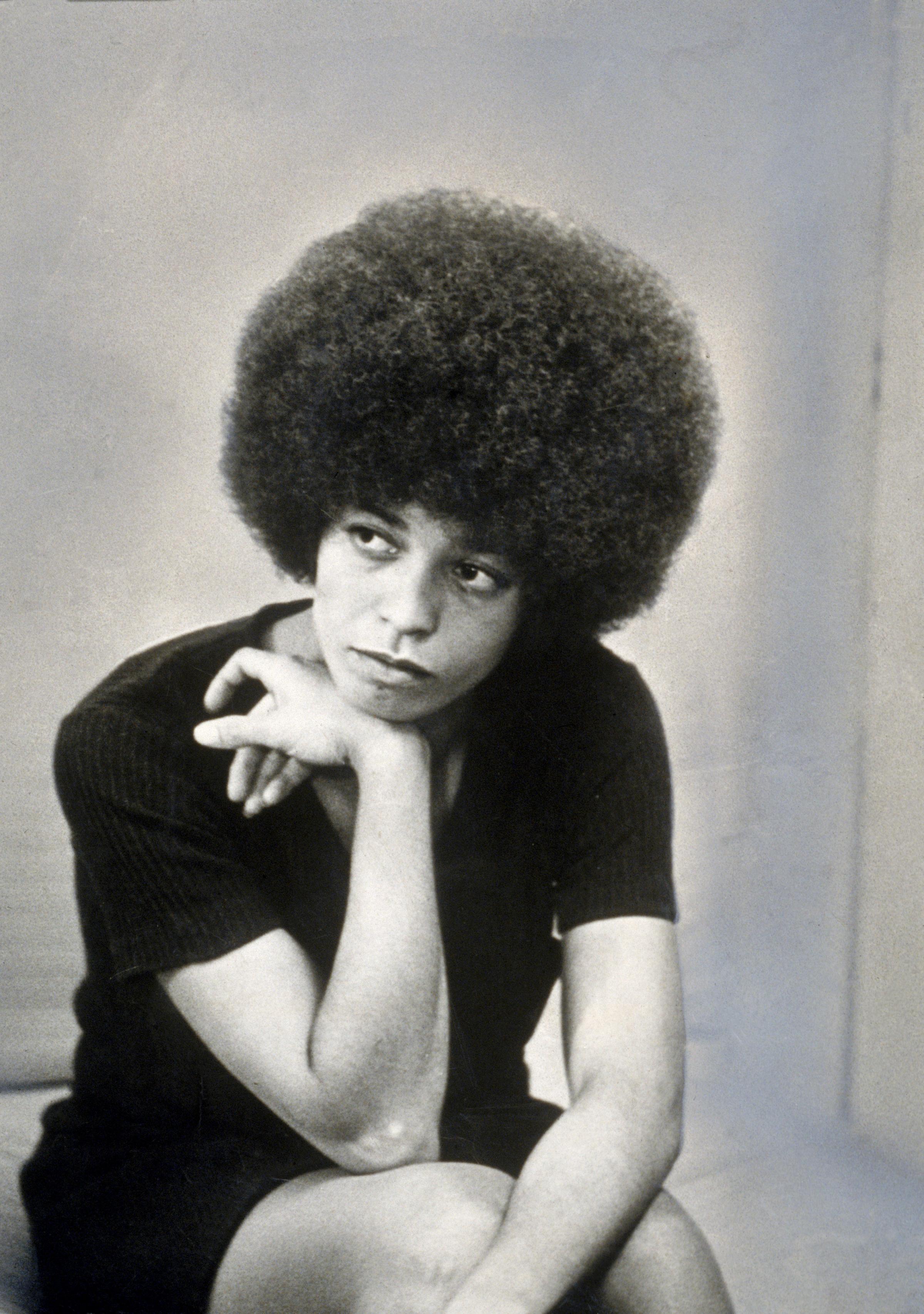

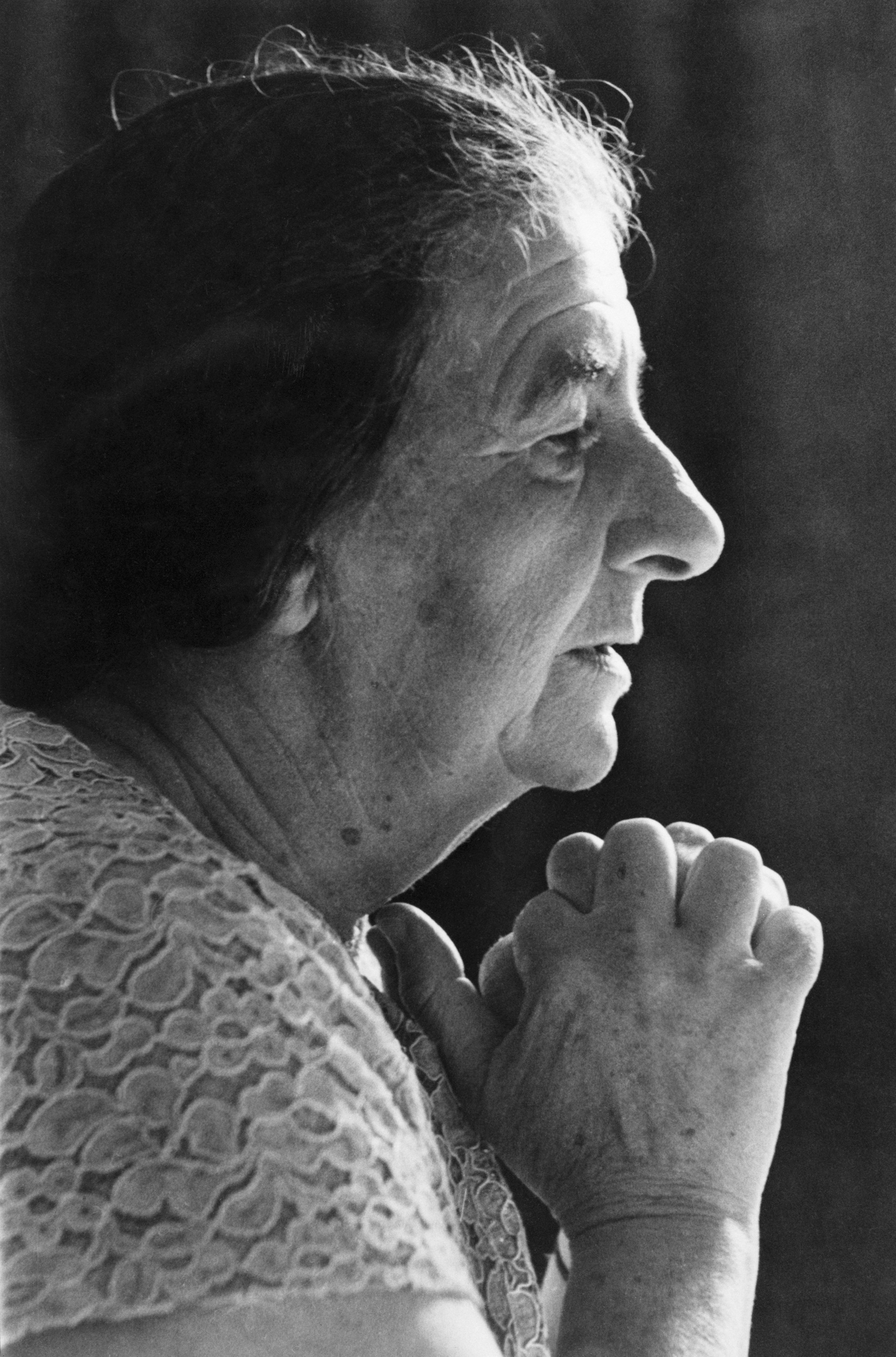

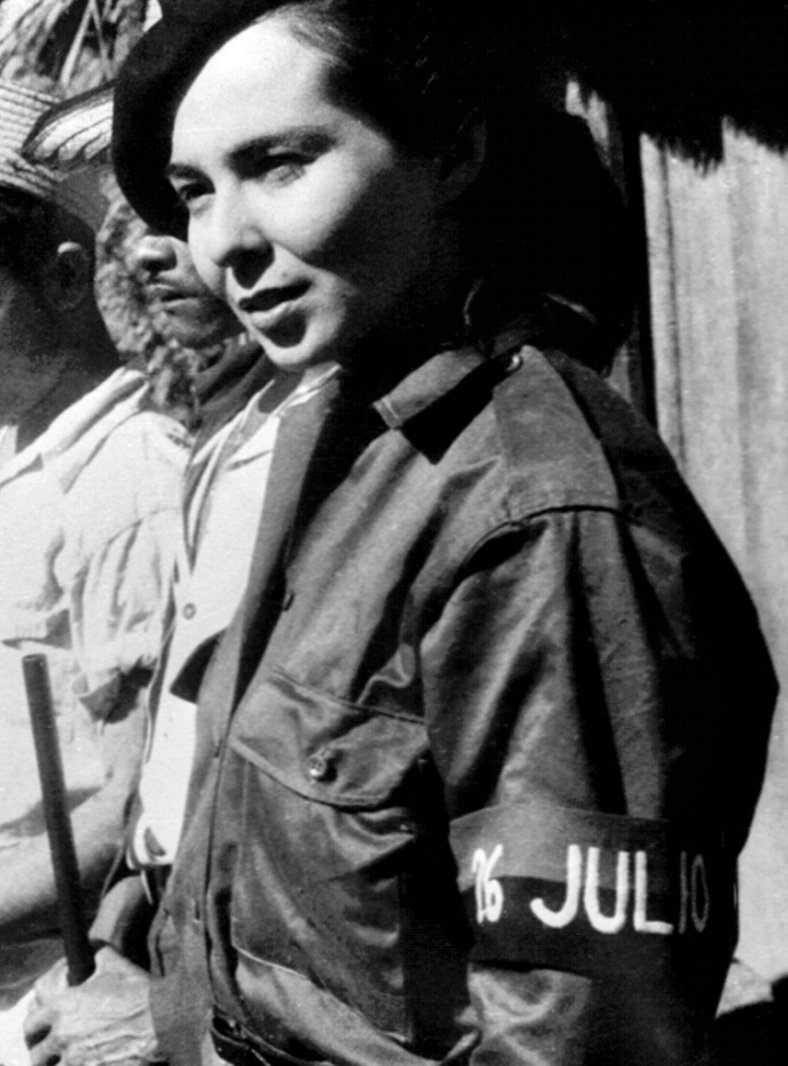

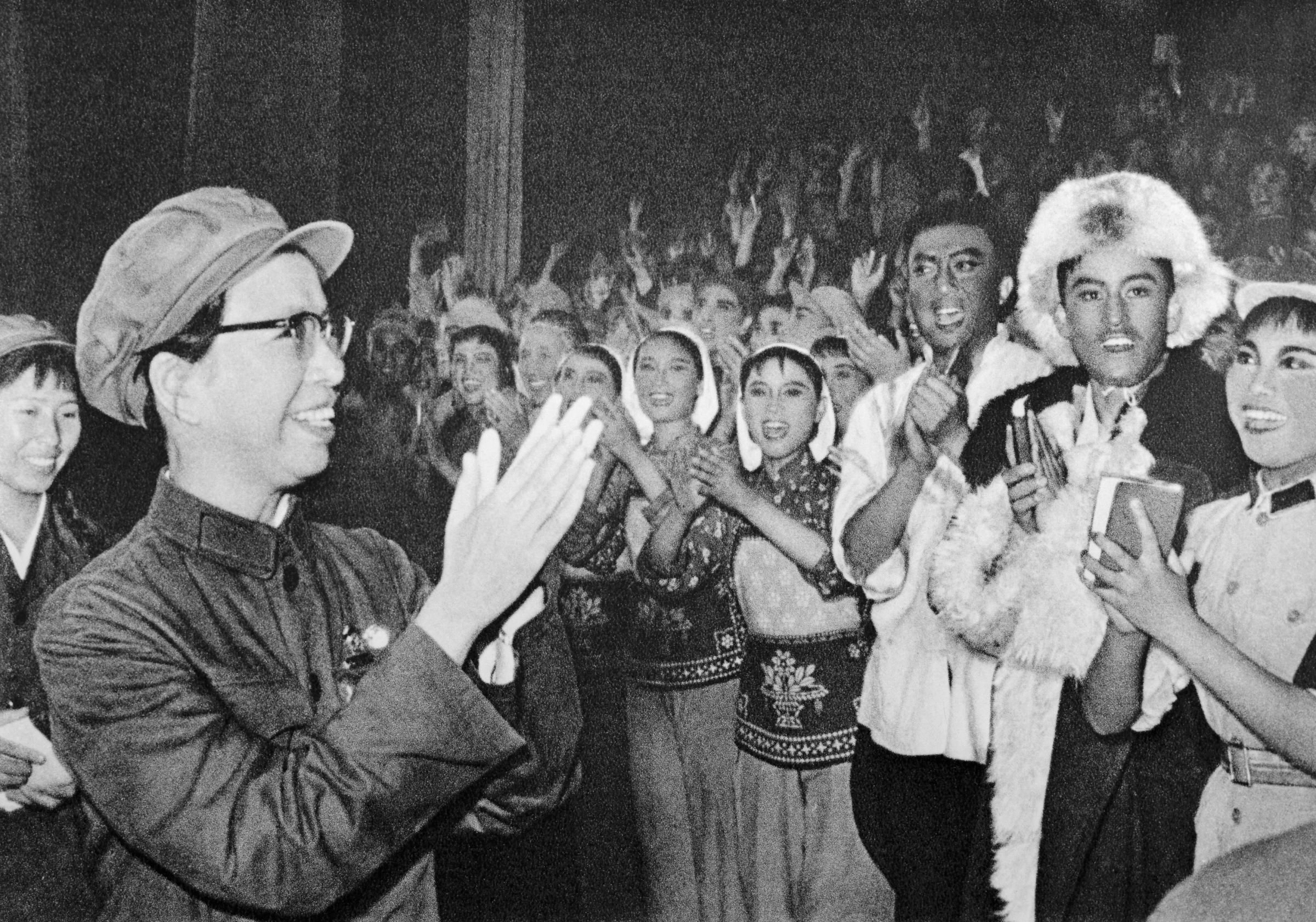

17 of History’s Most Rebellious Women

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com