I come here not to bury True Detective season 2. It did a good enough job of that by itself. The season ended much as it began, in a purple-prose haze of portent, masculine agony and confusion. It had too much plot and too little story; its murder mystery was so convoluted and foggy that, paradoxically, the show felt formless, like a string of long, unrelated audition monologues one after another. For eight episodes it turned and spun, like a driver on one of its complex California highway interchanges, circling and circling and never finding the right exit.

But True Detective will likely be back anyway. The ratings were still good by HBO standards, and the network has stood behind it, and creator Nic Pizzolatto, publicly. So we, and the network, might as well focus on what would make True Detective season 3 become something more than a source of funny Internet memes.

Simply: Nic Pizzolatto needs help.

True Detective is the logical progression, and most conspicuous failure, of something that has in many ways been good for television: the auteur principle of TV, the idea that a great series can and should be the expression of a single artist’s vision, like an author’s or (after a similar idea took hold in film) a movie director’s.

TVis historically a collaborative medium, because it has to be: there are too many moving parts and too many hours to fill for anyone to do it all. But the idea of the author-driven series has been growing in TV for decades, with network creators like Steven Bochco or David E. Kelley making series that–while they employed a lot of creative talent–spoke with a certain, distinctive voice. It grew in the late 1990s and 2000s, as writers like The Sopranos‘ David Chase and Mad Men‘s Matthew Weiner became celebrated as artists, organizing their shows around a single vision and intention. But even they had teams of writers: there were only so many superwriters like Aaron Sorkin and David Milch who either wrote or significantly rewrote nearly every script.

Pizzolatto, an author by background, was of that latter school, and that made season one of True Detective what it was, for better and worse. (Well, partly it did: you can’t underestimate the breathtaking directing of Cary Fukunaga.) That first season had definite weaknesses–it overdid the writerly monologues and suffered from flat characters, especially the women–but it sounded like nothing else, rich and haunting. Pizzolatto was using noir fiction the way detective writers did, as the greasy-spoon plate on which to serve an existentialist main course.

But Pizzolatto had the classic songwriter’s problem: You have your whole life to make your first album, and a year to make your second. He didn’t do it entirely alone (the fourth episode was the series’ first to feature a co-writer), but he mostly did. And it showed. There were flashes of beauty–YMMV, but Ray’s final, unsent recording to his son was lovely–but a whole lot of notebook-emptying. Many of the season’s weaknesses might have been improved by an empowered room of writers to talk back, cut the fat, handle fundamentals like breaking a coherent story. Yes, that would risk diluting the voice, but the 180-proof Pizzolatto we got this year could have used it.

Occasionally, the all-but-solo act can work, but it takes the right combination of talent, skill and circumstances. The most obvious example today is FX’s Louie, for which Louis CK writes, stars, directs, edits and all but runs the craft service buffet. But he has a couple advantages: he has experience both directing and doing the gruntwork of filmmaking, and he’s created a show that has the freedom to essentially be a series of short (or somewhat longer) films.

And even he, it turns out, needs a break. He’s taken absences of more than a year between seasons. This year, he made an abbreviated season of only seven episodes. And at FX’s presentation to the Television Critics Association press tour, the network announced that he was taking an indefinite break; like Larry David with Curb Your Enthusiasm, he’ll do another season when and if he’s ready.

One of the closest analogues to Louis CK in TV now is Lena Dunham, a film director making an arty comedy that’s more like indie film than a traditional sitcom. But Girls is also structured more like a TV series than Louie; it has continuity, it has multiple story arcs, and it’s been returning on a yearly basis. Dunham’s managed this by teaming with people who know how to make TV–Judd Apatow, and especially showrunner Jenni Konner–while still making a show that is unmistakably Dunhamesque.

What’s good enough for Lena Dunham would be even better for Nic Pizzolatto. Assuming HBO is not willing to wait years for another True Detective, Pizzolatto needs a team, professionals who can take a manuscript and turn it into a show. This doesn’t need to be a step back for TV as a writer’s medium; if it improves on the mess that was season 2, it will be a step forward. In a job as complicated as making TV, sometimes you need help to be yourself.

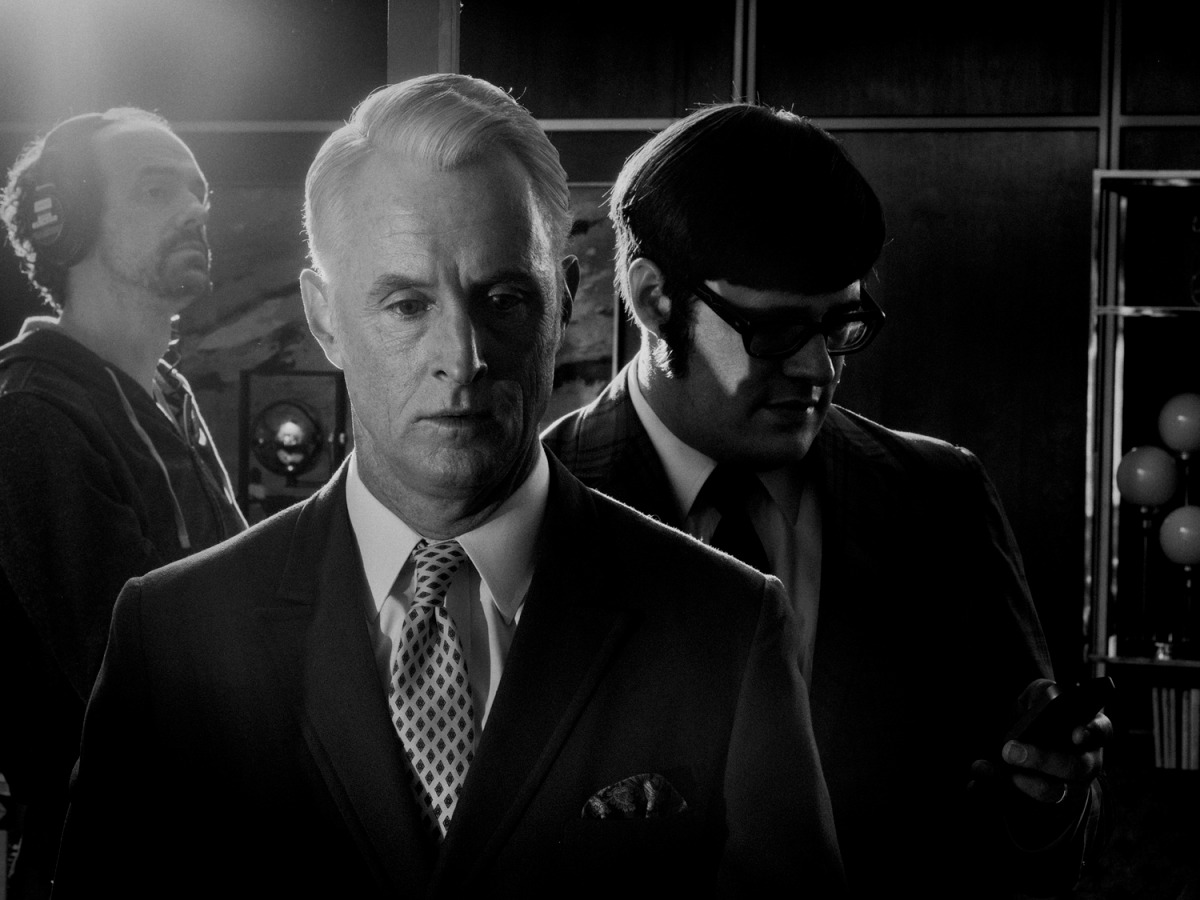

'Mad Men' Up Close: Photos From the Set of the Celebrated Show

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com