Donald Trump is no stranger to big promises and bigger disputes. But more than seven years ago, it was the people of Scotland, rather than the members of the Republican Party that were subject to his charm, flattery—and hard-nosed business tactics.

Trump, whose mother was born in Scotland, bought the Menie Estate in northeast Scotland in 2006 to build a golf course and luxury resort. He promised to invest $2.3 billion and create 6,000 jobs. There was just one catch: he needed to persuade some of his new neighbors to sell their property to him.

Susan Munro, now 62, whose home was encircled by Trump’s property, refused to sell. Trump tried to force her but when he failed she says his security guards routinely harassed her by stopping her car and asking for identification as she approached her home of more than 30 years. “It was horrible,” she recalls. “It happened on my own drive. I wasn’t even on his land.”

Munro never sold, but eventually Trump built a berm that surrounded her house and blocked off a large part of the scenery she had known for decades. “When I heard he was running for President, I just laughed,” she says. “But he’s a dangerous man.” George Sorial, executive vice president at The Trump Organization, says he hadn’t heard of Munro’s complaints. “With a handful of exceptions, and I am talking about two or three people, we don’t have any issues with people who live in properties adjacent to ours,” he says.

In 2009, Trump’s representatives asked the local council to use its legal powers to buy the property of Munro and her neighbors without their consent. The council declined but Trump’s staff reportedly continued to harass residents, trespass and damage property and cut utilities. Trump later fell out with the Scottish government over plans to build a small offshore wind farm, which he said would ruin the view from his course.

The resort in Scotland—Trump International Golf Links—is a much smaller enterprise than the businessman first promised because the majority of the investment has not yet materialized. “This is a long term project, we have a lot of work left” said Sorial, who has worked on Trump holdings in Scotland for nine years. “I have no doubt that the project will grow and eventually realize the numbers we initially projected.”

Trump’s battle with his neighbors was followed by filmmaker Anthony Baxter in his 2011 film, You’ve Been Trumped, who says that Trump made few friends in Scotland. “He talks about being the ‘jobs president’, about putting people into work in the U.S. All I can do is look at what I have seen over five years of filming his real actions based against the promises he made to Scotland,” he says. “He made the lives of those local residents a complete and utter misery, bullying them at every opportunity.”

While Trump’s tough-minded business style seemed unusual to Scots and other Europeans, his political style is familiar. Trump has called Mexican migrants “criminals” and “rapists,” sentiments similar to those endorsed by the populist leader of the U.K. Independence Party, Nigel Farage, who this year said that migrants with HIV should be banned from entering the country.

What unites Farage and Trump is their audience, who are “down at luck, working class white men who feel overlooked, forgotten or left behind,” says Alex Massie, the Scotland editor of the conservative current affairs magazine The Spectator. “They look at Westminster and Washington and see it’s dominated by these slick youngish men in sharp suits… a self-perpetuating political elite, who are out-of-touch from their experiences and they feel excluded from that.”

Trump and Farage have other similarities. They share a singular fashion sense and rarely seem to worry about the consequences of their comments, which helps them dominate the media. “Trump is great value for the media in the same way Farage was during the British election, being pictured with a pint in one hand and a cigarette in the other” says Baxter.

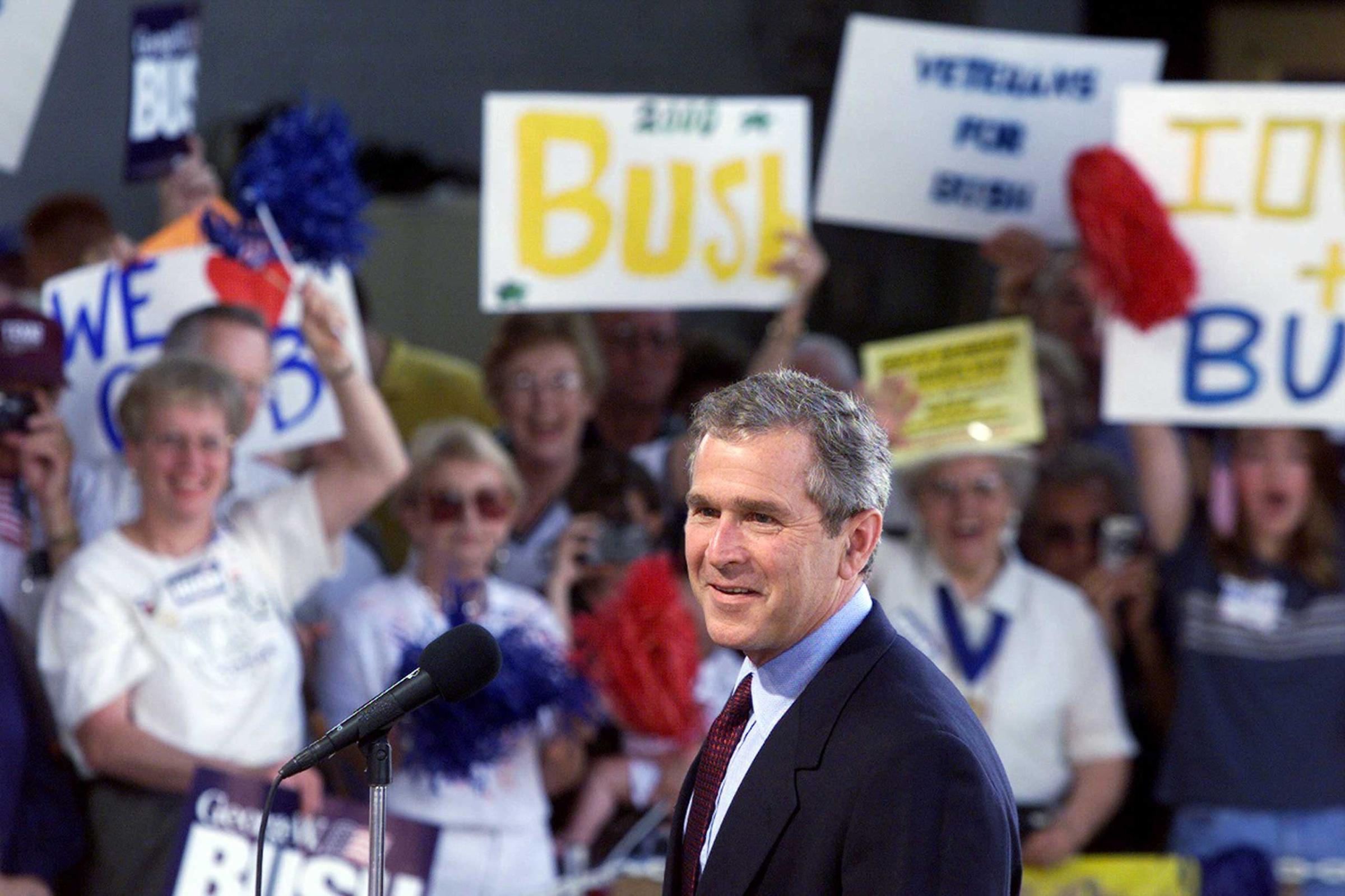

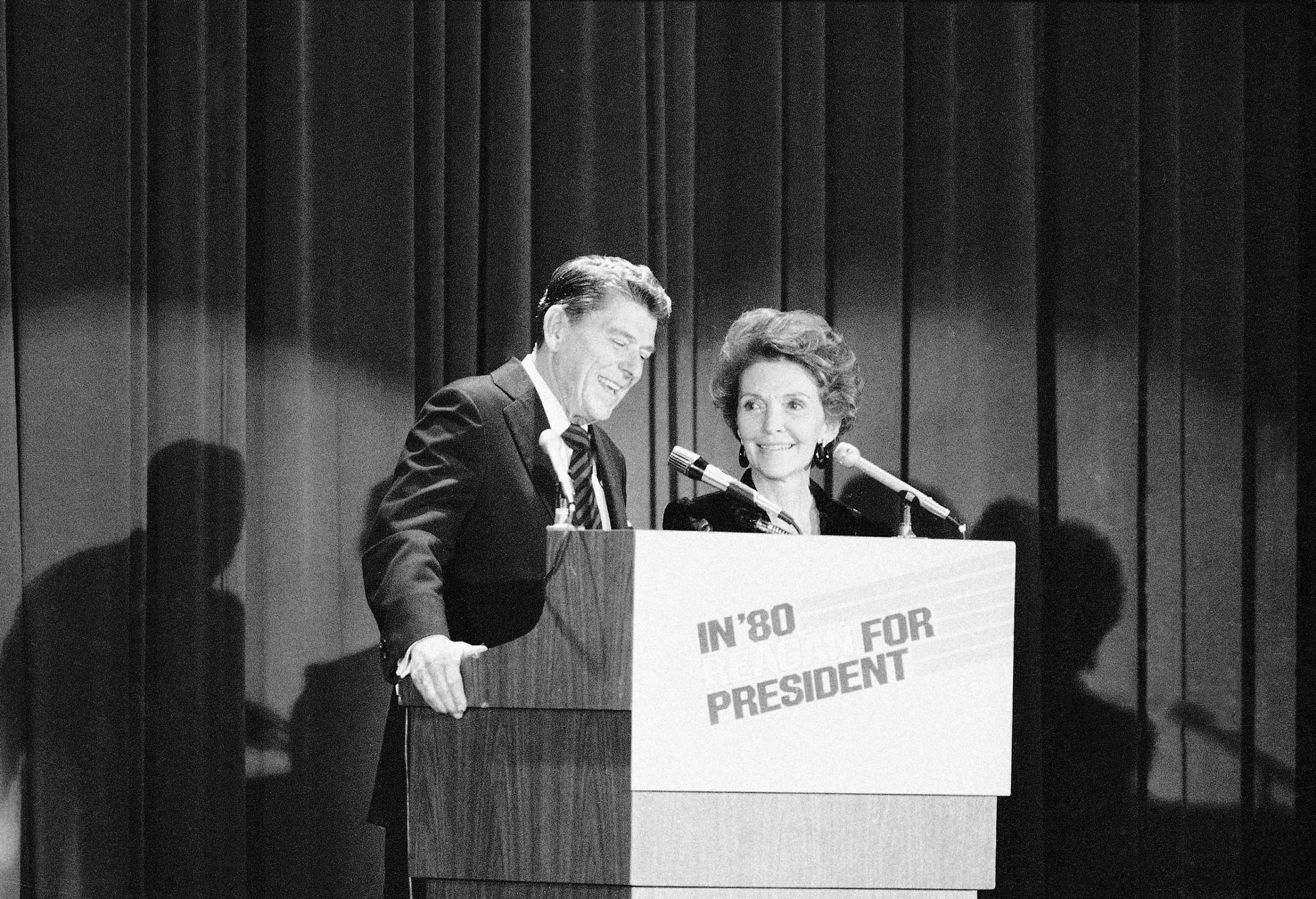

See 10 Presidential Campaign Launches

Mark Leonard, the director of European Council on Foreign Relations, says Trump, Farage and a host of other leaders in Europe are capitalizing on the inability of established political parties to effectively answer the anxieties of many sections of society. “They don’t feel that their viewpoint is represented by the mainstream parties by the left and right,”says Leonard, “and that’s what creates a space for populist politicians.”

Trump has capitalized on the same sentiments in America. “Whatever your issue, your cause, the festering problem you hoped would be resolved, the political class has failed you… and that’s what Donald Trump taps into,” said GOP candidate Carly Fiorina during last week’s Republican nomination debate.

What this means for policy is not yet clear. “Farage has a particular platform: withdrawal from the European Union, stricter curbs on immigration. Whatever anyone thinks about it, at least it’s an idea that’s just more than the personality of Nigel Farage,” says Massie. “Trump’s campaign, if you can call it a campaign, is a piece of performance art”—though the billionaire’s campaign has said that Trump will begin releasing policy papers.

Ivan Krastev, chairman of the Centre for Liberal Strategies in Bulgaria, believes Trump exemplifies a unique kind of populism. “He doesn’t have any great ideas,” says Krastev. “There are no clear policies, it’s all about him. He is not coming from the left or the right, he is coming from behind. It is a very strange sort of populism, which is strongly rooted in the nature of popular culture today. Extreme individualism, mistrust, being eccentric also plays a part.”

For Krastev, Trump has less in common with Farage than he does with Silvio Berlusconi, the flamboyant media tycoon who dominated Italian politics for almost 20 years. “Trump has the type of entertaining, cynical populism, which was typical of Berlusconi, who basically said ‘I’m going to take my mistresses and put them in parliament,’” says Krastev.

In 1994, when Italy was in the throes of a political corruption scandal, Berlusconi used the television channels he owned to announce the creation of his political party Forza Italia (Forward Italy). The Italian tycoon’s message was simple: he was a self-made media magnate who was going to fight for the common man. “The interesting story is you have a billionaire who said: ‘I’m revolting against the elites,’” says Krastev.

The $2.3 billion and 6,000 jobs Trump promised to put into Scotland turned out to be $150 million and a couple of hundred jobs, according to Baxter. “Trump isn’t the man of the people,” says Baxter. “He is the man of billionaires, who takes great delight in making exclusive, super-rich developments at the expense of ordinary people.”

Berlusconi was Italian prime minister three times for nine years in total while Farage failed to be elected to the House of Commons earlier this year. It remains to be seen which result Trump earns.

Read next: The Truth About Donald Trump’s Narcissism

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com