Is Sony’s PlayStation 4-exclusive Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture a game? An interactive narrative? An open-air museum? All three at once?

I’m not sure. I’m also not sure I care that I’m not sure. The whole “is this a game?” back-and-forth seems as silly as the “is this art?” debate. Either way, there’s a frame of mind angle involved in appreciating what developer The Chinese Room is up to. You have to be receptive to its calculated bell curve throw. There’s nothing to fight here, no puzzles to solve, no heads-up display, no larders to stuff (no inventory management) and no scores to settle. As far as I can tell, the game lacks PlayStation phphies, too. [Update: The pre-launch version I played had no trophies, but the launch version will.]

What you can do, is inch along at the speed of a snail, open and close doors and fences, and listen to cryptic audio clips that issue from ringing phones and portable radios droning strings of mathematically ominous numbers. That’s it. It’s “interactive” at roughly the level of an intricate museum exhibit with stations and those little buttons you can push to conjure audio vignettes.

Like Dear Esther, its spiritual predecessor, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture invites you to explore—or maybe the better verb here would be haunt—an uninhabited tract of bucolic Shropshire, U.K., conjuring memories that gradually brick together an elliptical sci-fi-tinged yarn, employing sharp-eared dialogue and promising buildup. Imagine the audio diary portions of BioShock, except here they’re the pièce de résistance, a trickle of tales that meld the terrifyingly inexorable with the inexorably personal. The end of the world isn’t really about the end of the world, but how, given time enough to brood, we’ll go about reacting to it.

But is Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture artful enough in its telling? The title alone seems to be telegraphing that it’s more than a mere sci-fi potboiler, what with its reference to apex eschatology. But is that reference symbolic? Ironic? Literal? I’ve finished the thing and I still couldn’t tell you.

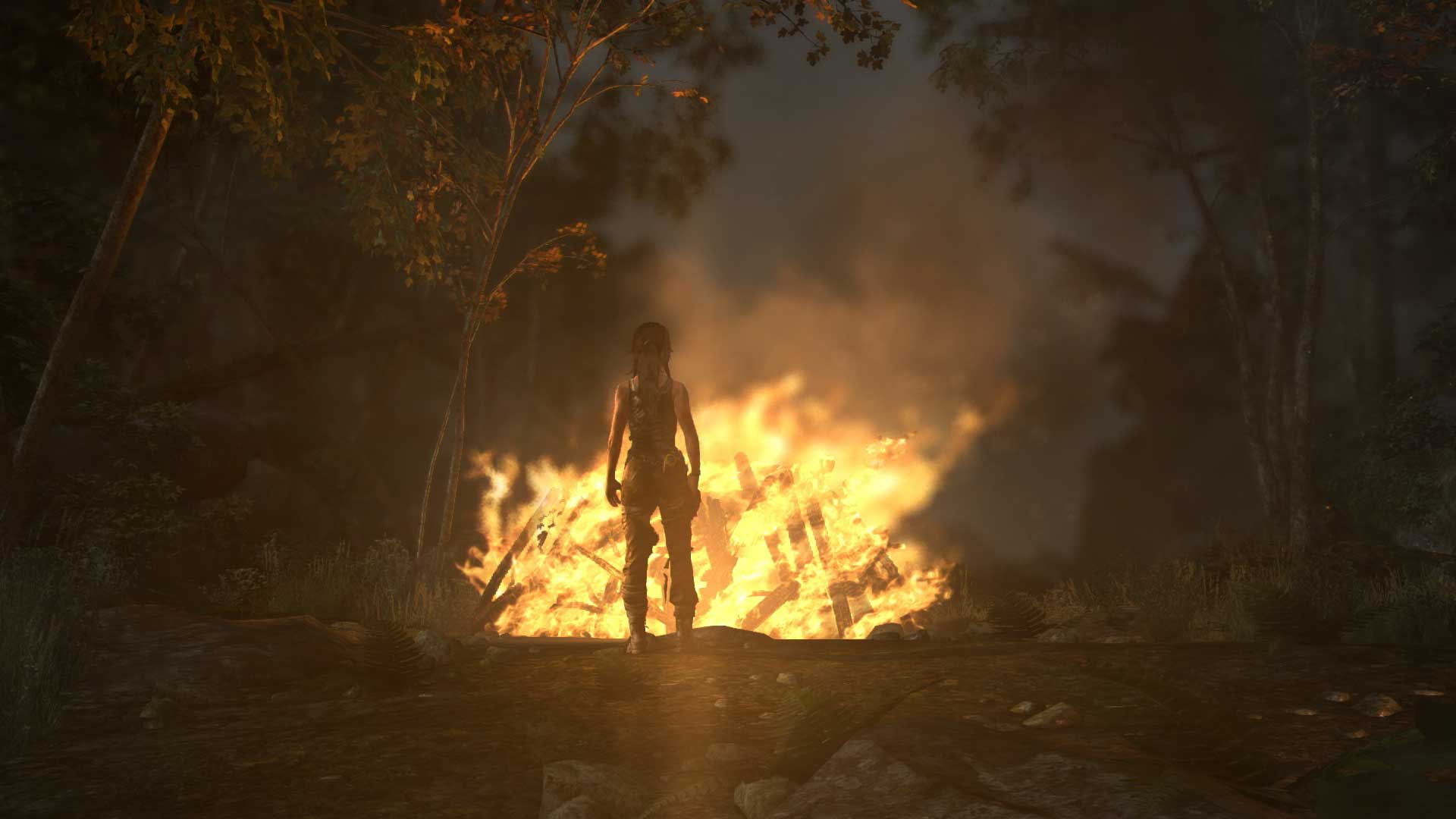

I can tell you the world wrought here looks as beautiful as a this-gen console game should, a sometimes linear, sometimes open swathe of blissful countryside you stroll freely through, espying mist-capped valleys punctuated by bus stops, phone booths, smoking ashtray-filled pubs, vast barns, spooky-looking domed towers, unpeopled flats, golden pastures choked with gently swaying strands of wheat and towering windmills. The weird stuff tends to happen as you amble along and trip (or interact with) trigger points.

In Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, that weird stuff mostly involves light that looks a little like the special effects circling Persis Khambatta and Stephen Collins near the end of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Balls of apparently sentient effulgence prowl intersections like terrestrial comets. Approach one and you’ll hear a susurrus of voices, like the doleful whispers in Lost. Are these the ghosts of the town’s unaccounted inhabitants? Often they’ll lead you to static spheres of energy. Twist the gamepad sideways (I’m not sure what this signifies, it just moves the sphere) and you’ll conjure a spectral memory, the sky blackening to starlight as a cyclonic stream of photons reenacts the scene, the actors physically unknowable save for their voices, which ring loud and clear as they recall a moment leading up to the “event” that culminated in their disappearance.

At first I assumed I was Kate, the first voice you hear as the game opens, a scientist with the laboratory partly responsible for the bit of scientific adventuring that gets the ball rolling. I gradually began to wonder whether I might be nobody, a bodiless phantom gliding from one slow-drip revelation to the next, poring over paranoid bus stop graffiti, the mishmash of artifacts in houses, bloody kleenexes, naturalist books on birds, old Commodore 64-style computers, black and white TVs, sky charts stippled with constellations, and “You are here” maps of the area as I worked out, mostly by following the beckoning balls of light, where to wander next.

Who you are may be a question the developers never answer. A disembodied witness? The actuating medium through which the roving souls of the transformed tell their tale? To what end? Perhaps simply this: to convey a straightforward story slightly out of sequence, with firmer visual parameters, the world and peoples our imaginations might conjure reading a book fully reified and continuously inhabitable here—mental flexibility versus imagistic holism.

That said, the navigational aids can be mercurial to a fault, and it’s easy to get lost once the areas open up. Couple with an inchworm’s gait, and if you mistakenly backtrack or veer off somewhere the little balls of light aren’t tracking, it can take more than a while to find your way back. Mountains of patience and an appreciation for romanticized English scenery are mandatory to seeing the four or five hours it takes to complete Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture through.

What worked least well for me, I hate to admit given my affection for Dear Esther, was the story. Not because it was unclear or poorly told, but because I’d argue it was handled with far more nuance and emotional resonance just last year in writer Jeff Vandermeer’s superlative Southern Reach trilogy. The twists and interpersonal tragedies and vaguely philosophical takeaways that should have been knocking my socks off here thus played more like the echoes of Vandermeer’s more affecting and weirdly analogous ones.

The things I like about Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture are many: the self-paced discovery and chronological asymmetry, the significance of entangling yourself in a visually “complete” environment, the poignance of a well-crafted, well-delivered character exchange. I’m just not sure how often I’d want to repeat the experience. It feels more like a playful experiment (there’s the “game”!) than a breakthrough approach to storytelling, though I admire the attempt, and the skill with which the tale, told in fragments, unfolds.

3 out of 5

Reviewed on PlayStation 4

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com