In India, a popular accessory may provide a wearable solution for a medical problem. A bindi—the traditional dot Hindu women wear on their forehead to signify the third eye of intuition–may soon become a much-needed source of iodine.

Grey for Good, the philanthropic arm of the agency Grey Advertising, is fueling the grassroots effort to provide women in India with a bindi that doubles as an easy, inexpensive way to get more iodine through skin absorption. The project, called the Life Saving Dot, is testing the bindis on women in rural parts of the west Indian state of Maharashtra.

The idea came to Ali Shabaz, chief creative officer of Grey Singapore, when he was thinking about new uses for wearable technology. Shabaz is originally from India and familiar with the practice among Indian women of wearing bindis. “Wouldn’t it be great if, in some way, this thing that women wore on their head could be useful?” Shabaz recalls thinking.

He also knew iodine deficiency was a problem in India. Iodine, a trace element which is most often associated with salt intake and found in seafood, is an important nutrient; without it, people can suffer from goiter, hyperthyroidism, stunted growth or intellectual disabilities—all preventable diseases. But iodine isn’t easy for some populations to get. Remote mountainous regions often have soil that is iodine-poor, and the consumption of seafood is frowned upon in some societies.

India is one country where iodine deficiency is a real threat. Many of its residents are vegetarian, and the soil is notoriously poor in the mineral. This combination of factors means that rural women in particular are at risk of suffering from iodine deficiency.

So Shabaz came up with an idea: to supercharge the bindi into a nutrition supplement.

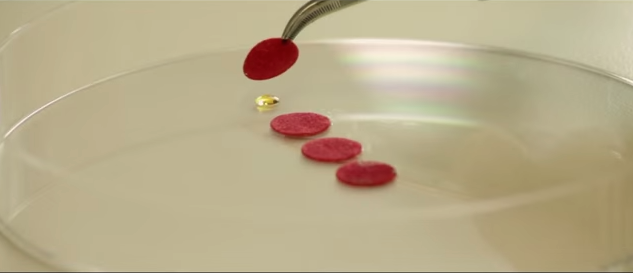

Grey for Good teamed up with Talwar, a prominent bindi distributor, and Neelvasant, an NGO doing extensive work in rural areas of the western Indian state of Maharashtra, five months ago. The group came up with a standard scarlet bindi with a twist: Each bindi’s adhesive came covered with 150-200 micrograms of iodine. Throughout the day, a woman wearing the iodine bindi absorbs on average 12% of their daily requirement of iodine, a marked improvement from before.

The Life Saving Dot uses the same technology and design as nicotine patches, and it’s cheap; production costs are minimal, Shabaz says, and are affordable at just two rupees per pack. (The rural Maharashtrian women Grey for Good worked with earned an average of 20-30 rupees per day.) Plus, wearing the iodine-infused bindi requires no behavioral change.

The campaign hopes to spread awareness about iodine deficiency, a problem that even the most vulnerable populations don’t always know exists.

Initial tests have been positive; of the approximately 150 women who have been given the bindis to wear, none have reported negative side effects and many have reported decreases in headaches, a common side effect of iodine deficiency.

“We’ve done allergy tests, which was important to us since this is right on the skin,” Shabaz said. “There were no side effects. What we’re running very soon is a sample size that’s much larger than before and across more varied age groups.”

There are still some shortcomings. Since bindis are worn by the country’s dominant Hindu majority, rural women of other religions aren’t going to reap the benefits. And while women face the brunt of iodine deficiency—pregnancy and birth often exacerbate symptoms and effects, making women particularly susceptible to the consequences of iodine deficiency—men are affected by the lack of nutrient in their diets, too.

Still, initial data from the Life Saving Dot have been promising for rural women—a group that is often ignored in Indian healthcare initiatives. Grey for Good is trying to attract the attention of the country’s political leadership to incorporate the bindis into their health initiatives and to help in distribution across the country. The creators of the Dot expect that sometime in 2016, rural Indian women can go to their corner shop, choose an infused bindi and fight iodine deficiency without a second thought.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Tanya Basu at tanya.basu@time.com