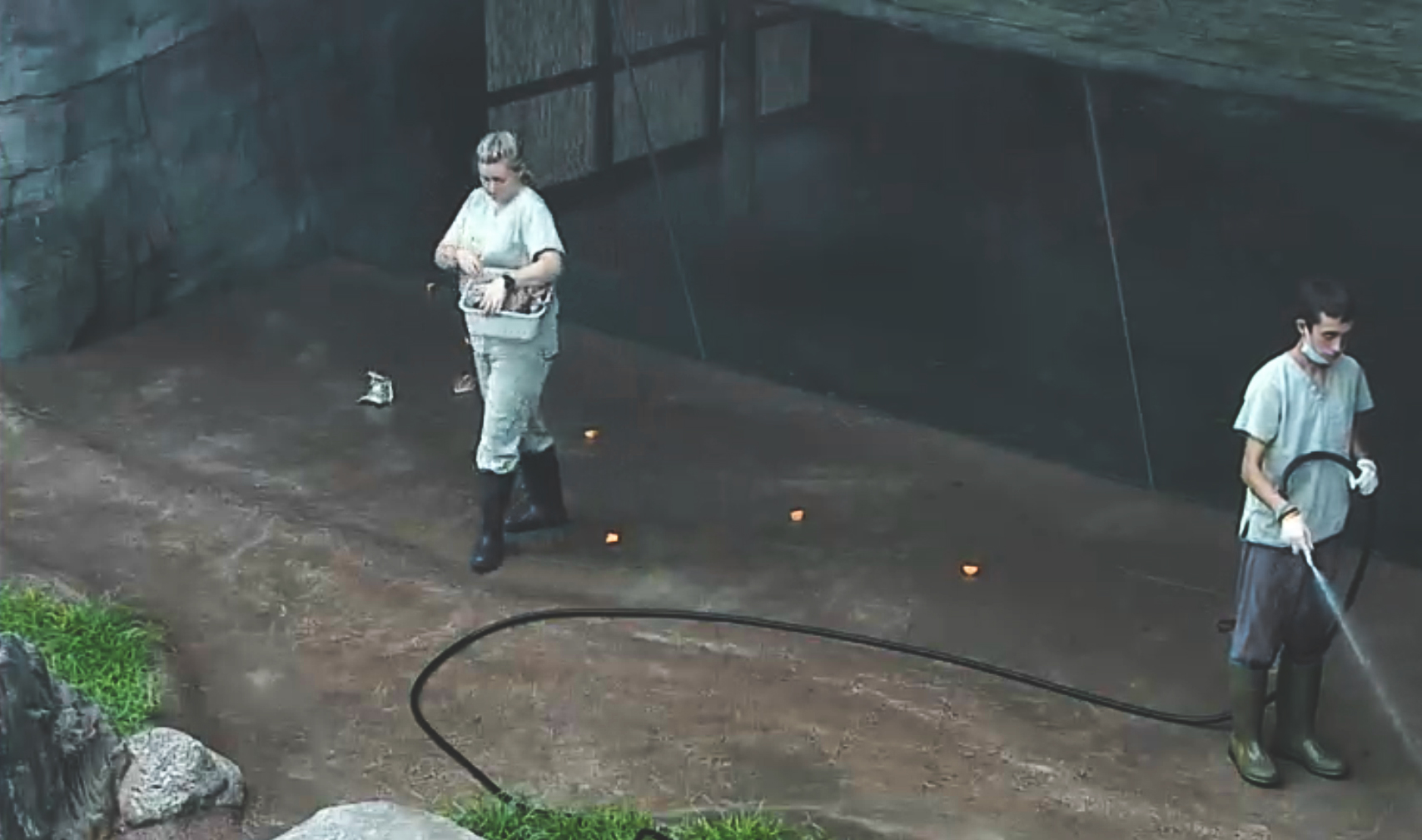

An orangutan appears to hit its own head with a swing. A panda huddles in the corner of a sparse, carpeted room. A leopard stands in an artificial cave, mouth ajar and eyes vacant, like a taxidermied museum exhibit.

These unsettling scenes come from the live surveillance video feeds of zoos in North America and Europe, frozen in time by photographer Arko Datto. Instead of using a camera, Datto made screenshots from the videos available online, revealing perspectives and moments of distress unseen during a typical zoo visit.

His series of images, titled CAPTIVECAM, is the third installment in a trilogy of “virtual” photography projects approaching issues through paradoxically hidden, yet publicly accessible means.

“I like to explore situations where the presence of a camera or photographer does not have a bearing on the subject, which brings me quite naturally to the idea of live camera feeds and surveillance,” he tells TIME. For Datto, who holds master’s degrees in theoretical physics and pure mathematics, virtual photography is a way to combine his interest in contemporary social issues with his background in abstract conceptualization.

His first work, CYBERSEX, offered a glimpse into the world of virtual prostitution in between paid sexual performances. His second, CROSSINGS, took viewers on an aerial voyage across the Arabian Desert, meditating on societies built by enslaved migrants. Though research for CAPTIVECAM began in 2013, he only recently became sensitized to the plight of animals, motivating him to finish the work.

Datto draws eerie parallels between the surveillance of animals and institutional surveillance of humans, likening the experience of watching the zoo feeds to seeing security footage of himself in subway stations and malls. “I come away with a strong feeling of disempowerment, and a strong sense of power imbalance,” he says. “Sentient beings in themselves, [animals] are spied upon constantly by humans, by our physical or virtual presence.”

The psychological effects of captivity on animals, according to Datto, also bear an uncanny resemblance to those on people. “You can observe stress and boredom,” he says. “You can observe repetitive behavior, including pacing back and forth, like in some perverse Sisyphean drama.”

Defenders assert that zoos provide a genetic reservoir for long-term species preservation, contribute to a knowledge base for conservation research, and have educational value to the public. But Datto argues that there is a corporate-industrial nexus set on profiting at the expense of animals, with very little going towards ensuring their survival in the wild.

“Look at the cold business attitude on display when it comes to the economics of the giant panda, from the Chinese government side to the American zoos that host them,” he says. “My point with this work is to make people aware of the various facets of what they see in context of the zoos.”

Datto dreams of a day when animals are put in zoos for the greater good of their species rather than profits. Better yet, they wouldn’t have to be in zoos at all. “These are intelligent, sentient beings that are confined in enclosures, however good the enclosures might be,” he says.

Arko Datto is a photographer based in Kolkata, India.

Jen Tse is a photo editor and contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter @jentse and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com