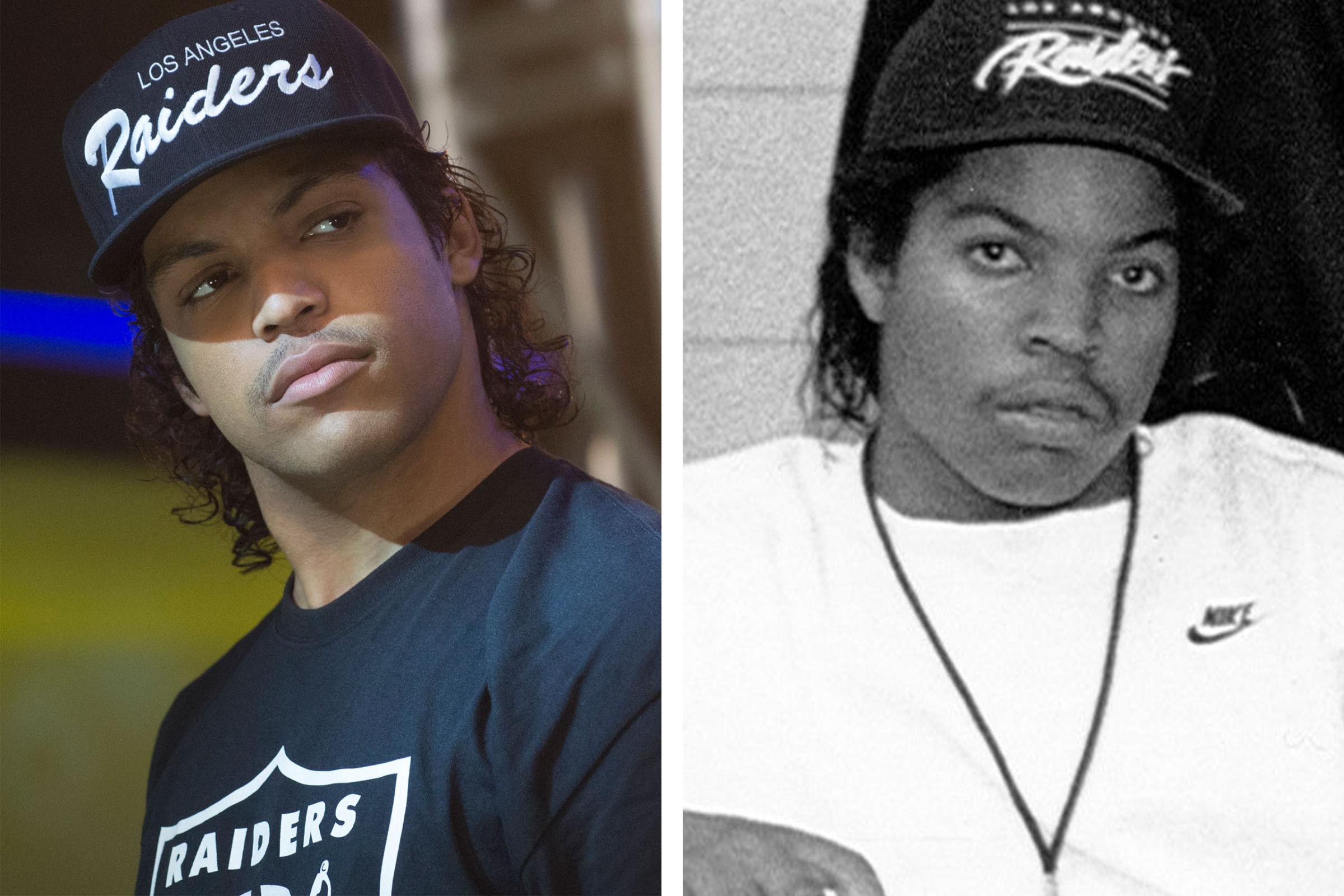

Ice Cube has a close personal connection to Straight Outta Compton, and not just because the hip-hop biopic chronicles his time with the pioneering rap group N.W.A.—the actor playing him is his very own son. But Cube is quick to point out that this is no case of nepotism. Not only did O’Shea Jackson Jr. have to win over the filmmakers with an audition like every other actor in the film, he also had to overcome his father’s skepticism. “Sometimes you ask your kid for something, and when it’s really time to really go and do it, they start to back out,” says the rapper-actor, who also produced the movie as well. Cube talked to TIME about police brutality, the Drake-Meek Mill feud and the enduring legacy of “Bye, Felisha.”

TIME: What’s it like watching your son play you? It must be surreal to see him rap along to your music.

Ice Cube: I think he did a great job. I was truly impressed. He was so convincing. All the guys did such a great job, so I don’t know if surreal is even the word. He’s lining up a nice career ahead of him.

How did you help your son prepare for the role?

I gave him all the tools he needed. I really wanted to see if he was serious and focused. Sometimes you can ask your kid for something, and when it’s time to really go and do it, they start to back out. The first test was getting him a coach to work with, and to start locking in these scenes he had to pull off. He was all in. He had a great relationship with the coach, and he just did everything he was asked to do. Other than that, I would just tell him what I was thinking, my perspective on the situation, how I was feeling about it, how I was feeling about other people in the situation. He said it helped. I just wanted him to have enough ammunition. If he had to ad-lib, he’d know where to go.

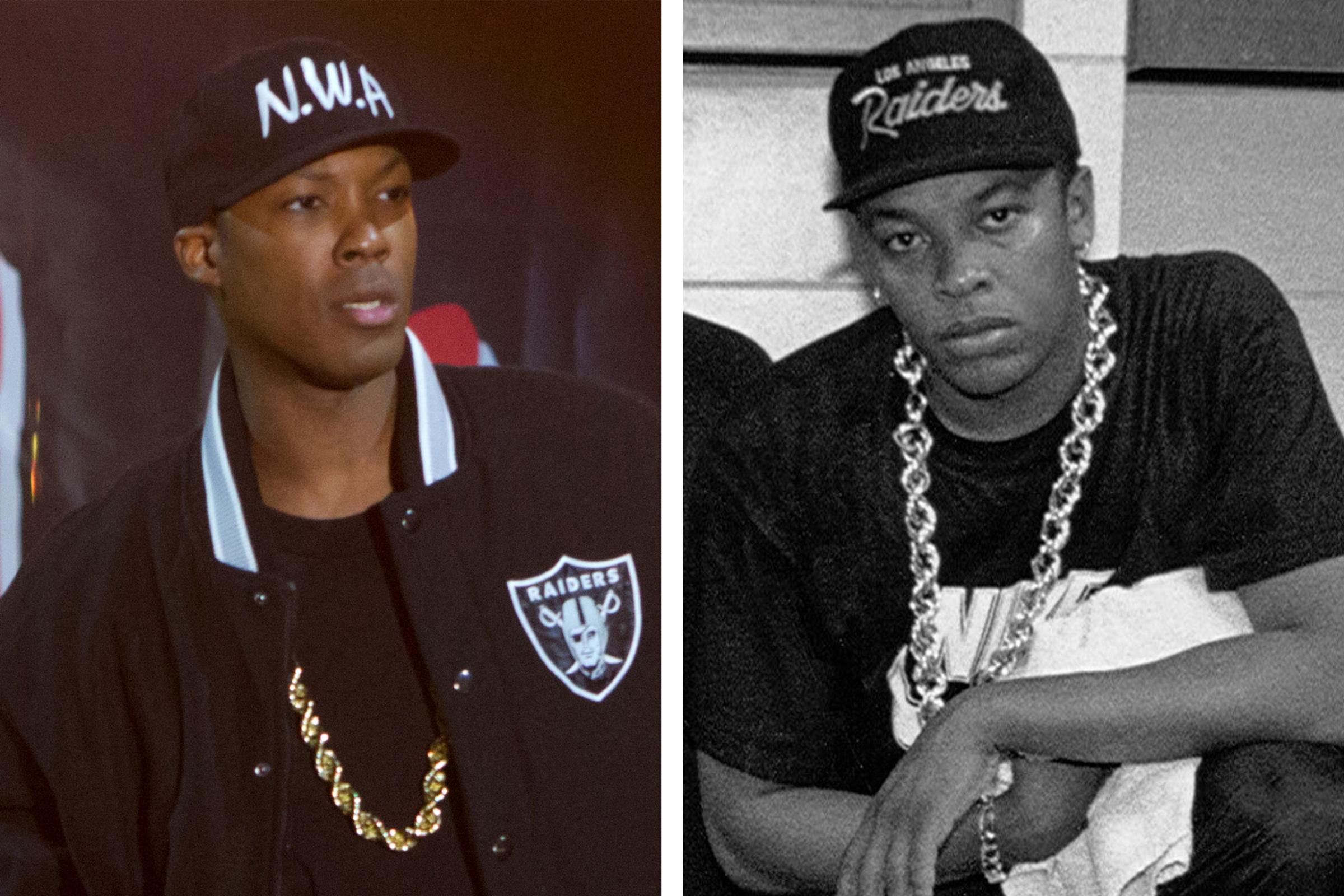

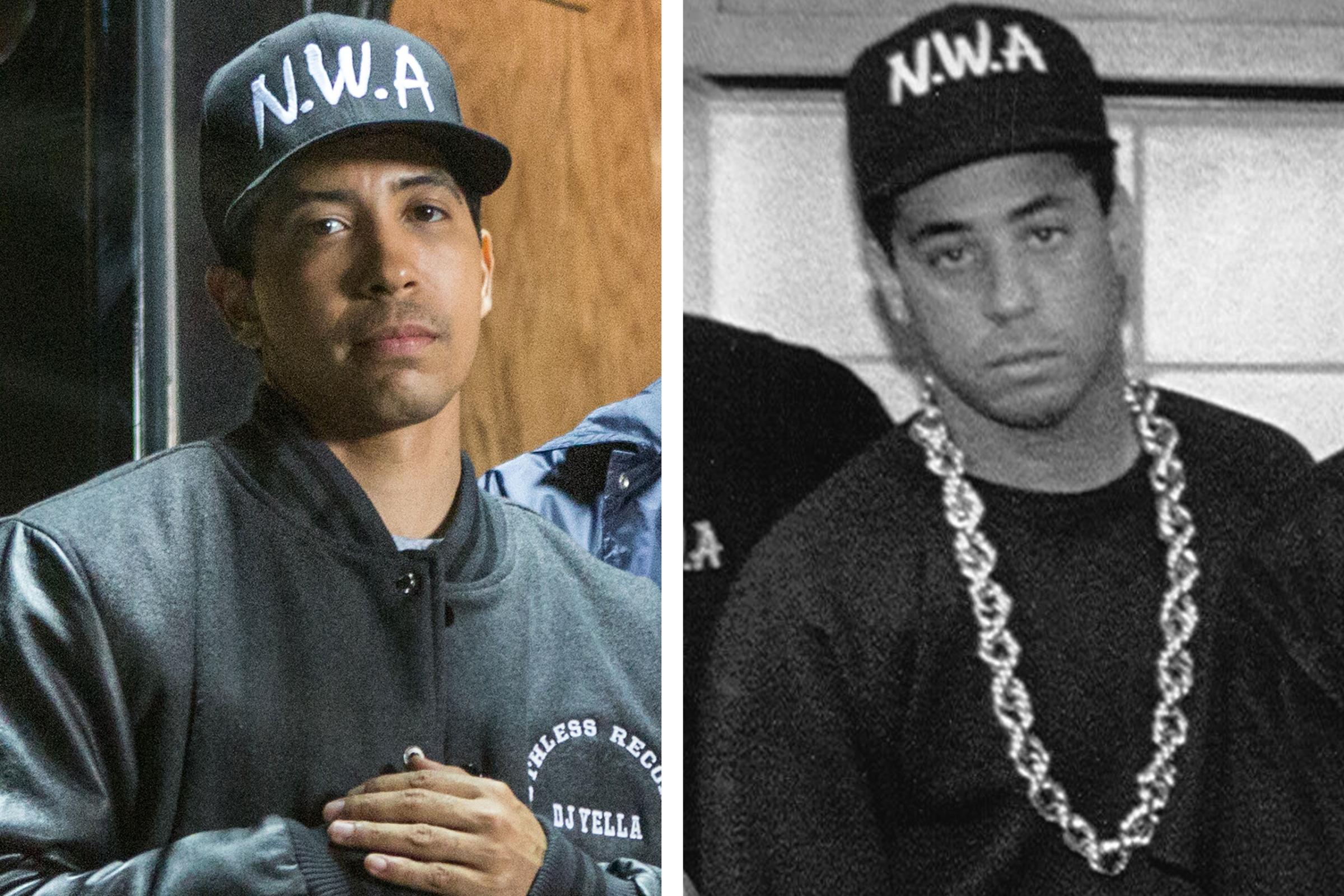

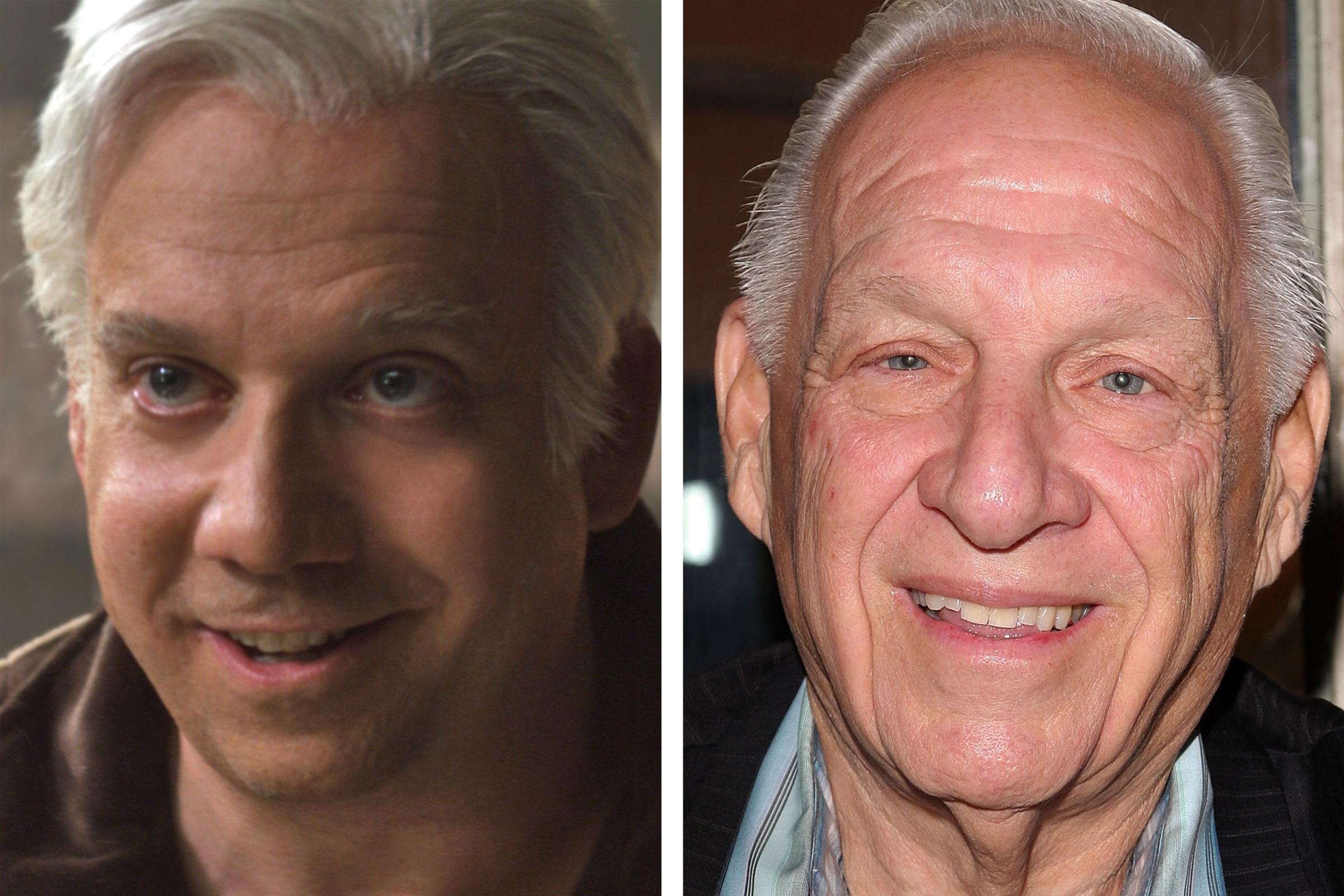

Here’s How the Straight Outta Compton Actors Compare to Their Real-Life Counterparts

Whose idea was it to put the “Bye, Felisha” joke in there? [The character’s named is spelled with an “sh” in the movie.]

That was O’Shea Jr.’s idea, him and [director F.] Gary [Gray]. They were just talking about it on the day that it was just a perfect set-up to end the scene with. The girl in the scene was named Felisha. Gary had directed Friday. The synergy was just perfect. They went for it, and I’m glad they did.

Has the line’s Internet popularity turned a whole new generation onto Friday?

People discover it all kinds of ways. With “Bye, Felisha,” it seems to have had a surge in popularity over the last few years. It’s a line in the movie that I never thought anybody would even pay attention to. It’s kind of matter of fact—I guess that’s the reason why it worked. I’m never shocked at what people pull out of Friday and run with.

What was it like working on this film last year as the conversation around police brutality reignited?

It was mentioned, but it wasn’t really dwelled on. We were trying to give people a slice of why we created the kind of music we created. That was the key, to really show people the why. Compton is a character in our movie. Compton is the sixth member of N.W.A. in this movie. It just happened to come out at a time when there’s so much other police abuse in the news. I knew that whenever we dropped this movie it would be timely because problems still persist, which is really a shame. It’s nothing for us to hang our hat on at all. I’m not surprised. It’s not shocking. Nothing has changed. We haven’t held enough officers accountable for misconduct and abuse and, in some cases, just flat-out murder.

The film also shows how predatory the music industry can be, particularly in its portrayal of music manager Jerry Heller, played by Paul Giamatti. Is it still that way today?

Of course. There is a long line of snakes out there. It’s not purely just a white guy taking advantage of black guys. You have black guys taking advantage of black guys, white guys taking advantage of white guys and everything else in between. Money really only has the color green. It’s the music industry—if you don’t know your business, someone’s going to take advantage of you.

You’ve compared your rapping with N.W.A. to journalism in the way it documented the realities of your environment. Which rappers taking up that mantle today are on your radar?

A lot of rappers do it on a song by song basis. Most artists have at least one or two songs where they are talking about how they grew up or real-life incidents that go on. But the rappers who choose to do it the most and are starting to really make a name for themselves and stretch out above the rest are J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar. Kanye doesn’t have a problem putting his true feelings on the music. There are a few artists still trying to hold the torch when it comes to having something to say or being thought-provoking.

Straight Outta Compton shows in the early days of N.W.A. rappers collaborating, passing around lyrics and deciding who should rap what. What do you make of the conversation around ghostwriting that’s happening in rap right now amidst Drake and Meek Mill’s feud?

It’s always been controversial, but I always think about it like this: if you’re making a record, that’s one thing. A lot of records have been made by committee. That’s not the issue. If you want to be a battle rapper, or if you want to be respected as a true emcee, you should write your own rhymes. If you’re making a record, it don’t matter what you need to do to make a record to come out good. All people care about is how the record sounds, not how you put it together. Nobody every bought a wack record because they like they how it was put together. Ghostwriting has been here as long as music and singing has been around. It just depends on what you choose to be.

Your N.W.A. diss track from after you left the group, “No Vaseline,” is prominently featured in the movie. Do diss tracks still have a place in rap in 2015?

Yeah, they sure do, with what’s going on with Meek Mill and Drake. It’s always going to have a place in rap. It’s actually the foundation in a lot of ways. A lot of battles have sparked careers—and ended careers.

I think what struck me about Drake’s first diss track “Charged Up” was how little time it actually spent dissing Meek—it was almost an anti-diss track.

I just think it’s each person’s approach. My thing is, if you gon’ diss, you should go for the jugular.

You’re more prolific than Dr. Dre, who just released his first album in 16 years after feeling inspired by working on Straight Outta Compton. But has the movie rubbed off on you creatively at all?

I’m definitely inspired by the movie. I’m always inspired by life to keep writing, to keep having things to say. Not every record is a political opportunity, but when I choose to do it, it’s usually really about the things I’m dealing with, or the things I’m witnessing, the things my people are dealing with that I think I need to speak on.

What was it like revisiting the music? The songs sounded fantastic in a movie-theater setting—I was expecting them to sound more dated.

That was a whole different era, the sample era. The songs that we sampled are pretty much exhausted. It’s been run through. It’s really the era to create new music and fresh music, create your own music. That said, I listen to my tracks all the time, I perform a lot, I still tour. To hear it in the theater is cool, but these songs have been playing in my house since they were recorded.

Yeah, and the politics of sampling in music are so different today.

Back in the day it was the wild west, and then people started controlling their sampling situation. A lot of publishing companies started overpricing the samples, wanting to own 100 percent of these rappers’ songs. It doesn’t make sense.

Looking back, what surprised you most about the group’s history as you revisited this story for the movie?

There were a lot of things that went on after I broke up with the group that I didn’t know about, that I learned about doing the research for this movie and interviewing everybody about what they were going through. It was a discovery for me. I was like, “Yo, this movie gonna be great!” I had no idea Eazy-E was going through financial issues, that was something, or that Jerry Heller had even misled him. These kinds of things were very, very eye-opening.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Nolan Feeney at nolan.feeney@time.com