Need your dystopian world liberated from oppression? That’s totes not a problem. Just ask a teenage girl.

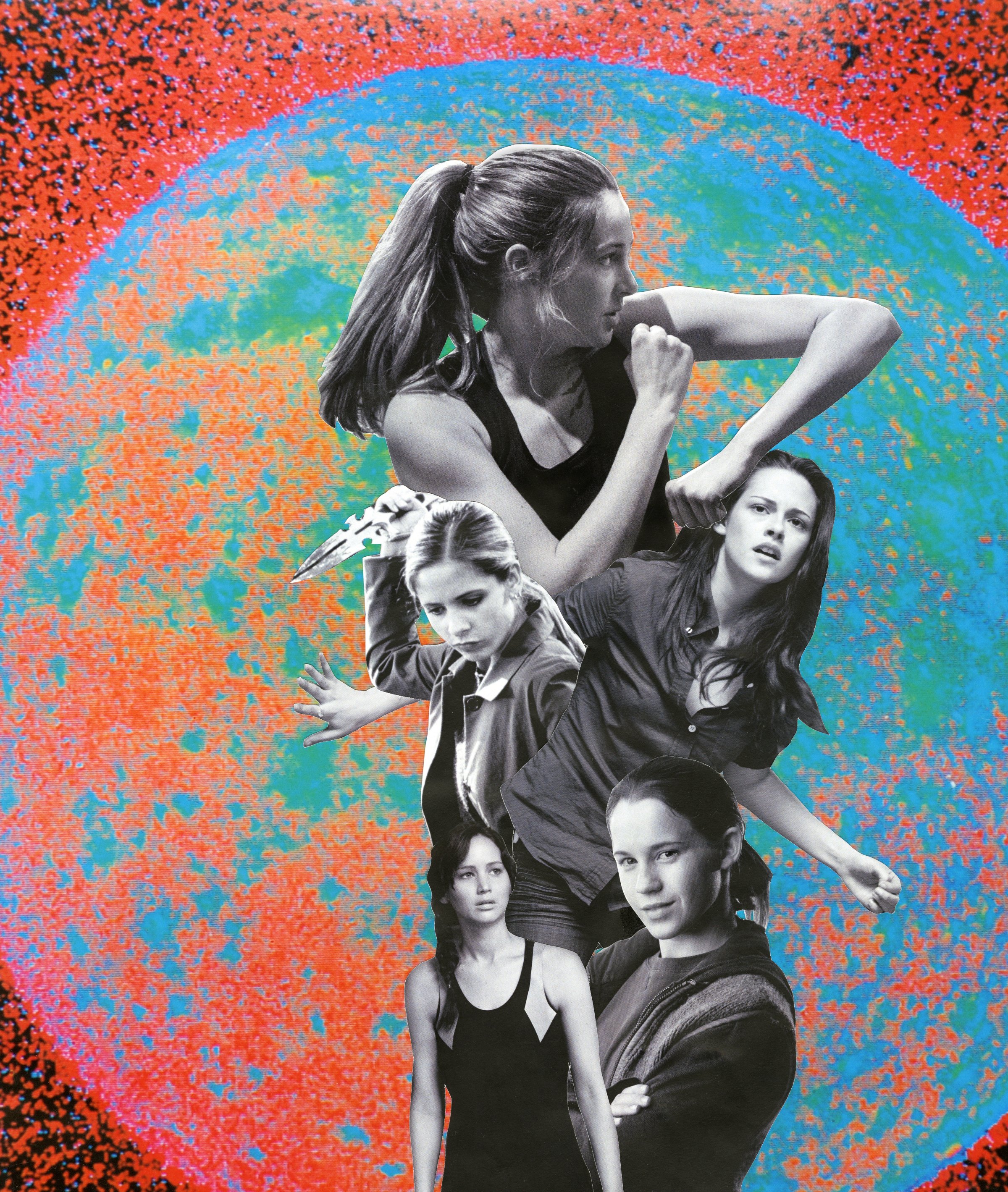

The latest rage in Hollywood is heroine chic, action thrillers that celebrate plucky young women who outwit, and sometimes outmuscle, totalitarian regimes. Though women have been fighting on film for decades, their ranks are newly swelled with dystopia girls, futuristic young ladies–like Beatrice “Tris” Prior of the new film Divergent–who take on the Man.

Just five years ago, the year’s 100 top-grossing movies didn’t include a single one about a teen girl saving the world of the future from a deadly authority. Last year Katniss Everdeen powered The Hunger Games: Catching Fire to become the No. 1 U.S. movie of the year. Though superheroes are still strong performers, the era when the buff and buzz-cut male lead was the only one who could do the job is over. To wit: Divergent hasn’t matched The Hunger Games in hoopla or opening-weekend earnings, but its $54.6 million draw topped the openings of Elysium and Oblivion, recent postapocalyptic vehicles starring Matt Damon and Tom Cruise.

At first, Tris’ story–based on a trilogy of young-adult novels by Veronica Roth–sounds like the pitch for a movie that might have starred one of those old-school dudes with a gun. She lives under a regime in which citizens are assigned to one of five factions on the basis of a personality test; familial and romantic love are subsumed by faction loyalty. She doesn’t fit neatly into one–she’s, you guessed it, divergent–so she sees how sinister that system really is and fights back. Dystopia girls face the same obstacles as their male counterparts. They aren’t afraid of weapons–note Katniss and her facility with a bow and arrow–though they use their brains too. They do fall in love, but saving humanity comes first. They’ve also got something that men fighting those battles lack: hordes of teenage fans.

Dystopia girls are legion and bound to stick around for a while. There are still two more Hunger Games movies to come and two Divergent books to be adapted, and lots of books that share shelves with those series are in development as movies, like Marie Lu’s Legend and Ally Condie’s Matched. Young women are even creeping into the traditional dystopian canon: casting news for Equals, an upcoming movie based on 1984, was dominated by word that Kristen Stewart of Twilight fame would star. “Having the balance between strong, empowered men and strong, empowered females is really important,” says Shailene Woodley, who plays Tris.

The dystopia-girl archetype grew from what were two distinct literary traditions, previously kept apart by convention, says M. Keith Booker, a professor at the University of Arkansas who studies postapocalyptic narratives. Mainstream dystopian lit, of which 1984 and Brave New World are seminal texts, had adult, male protagonists. Teen-girl stories were separate, even when their heroines fell–literally, in the cases of The Wizard of Oz and Alice in Wonderland–into situations that might merit inclusion. Alice and Dorothy gave rise to the heroines of A Wrinkle in Time and Buffy the Vampire Slayer as well as less feminist-friendly fare like Twilight.

Then, even before The Hunger Games, the traditions began to merge. Booker says economic forces may be responsible. “I think one of the reasons these books have been appearing is, frankly, just the expectation that teenage girls read more books than teenage boys do,” he says. “Even though teenage girls have traditionally read Harry Potter and that sort of thing, it does seem like a reasonable idea from a marketing standpoint to have teenage-girl protagonists.”

Our Stories, Ourselves

Still, that shift wasn’t just a matter of money. Veronica Roth, who wrote Divergent, grew up loving books like The Giver and Dune, happily identifying with their heroes. The best fantasy stories were about boys and men. That didn’t seem weird. It wasn’t till later that she noticed it: boys weren’t conditioned to identify with female characters in the way that girls were to see themselves in Harry Potter or Han Solo.

Girls who like to read fantasy and science fiction aren’t a new phenomenon. What’s new is that they’re demanding to see themselves in the lead. And, finally, they are being heard–most often by female writers like Roth, Hunger Games’ Suzanne Collins and even Twilight’s Stephenie Meyer. Divergent is part of a growing awareness about how important it is to see oneself represented in the media. It comes on a wave that carries not only the dystopia girls–from movies, books and TV shows like Revolution–but also other female protagonists in traditionally male roles, from Gravity’s astronaut adrift to Frozen’s queen saver. Same goes for girl-friendly toys like GoldieBlox and viral videos like the one by a dad who altered Donkey Kong so his kid could play as a woman rather than as Mario.

“It’s just time, culturally,” Roth says. “Young women are starting to say, ‘Hey, I am an audience that you need to pay attention to, and this is what I want. I want to be the main character in the story.'”

Audience demand–a new status quo in which girls refuse to watch the action without participating–means that even if the mania for dystopia girls diminishes, the hybrid archetype is here to stay.

“The fact that it’s a young, female character is a nice alternative to a Superman or Batman,” says Miles Teller, one of Woodley’s Divergent co-stars. And since pop culture can’t go back to a world where audiences think girls don’t know how to fight their own postapocalyptic battles, those women won’t be “alternative” for long. They’ll just be heroes.

Which is a good start, according to Roth, but it doesn’t mean the work is done. Katniss and Tris, like Dorothy and Buffy before them, are a new but narrow group: young and able-bodied, represented by attractive white women. Those girls aren’t the only ones hungry to see themselves save the world. There are signs of expansion already–Roth singles out the author Malinda Lo, for one, for her inclusion of gay characters–and if Divergent and The Hunger Games are any indication, that’s where Hollywood may go next.

“I’m hearing a lot more calls for different types of heroes, not just the gay best friend but the gay hero, not just the black best friend but the black hero,” Roth says. “People are clamoring for it a little more, and I think that’s a positive sign. It means that things will start to spread.”

–With reporting by Emily Zemler

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com