Fifty-three years ago, the actress who began her life as Norma Jeane Baker was found dead in her Brentwood home. The details surrounding her death are as foggy in the present as they were that Sunday morning in West Los Angeles. At the time, the announcement of her premature death seemed like the tragic third act of a densely plotted crime novel. The sad reality of the news traveled quickly, disseminated to all points east.

The headline on the front page of the Detroit Free Press read: “Marilyn Monroe is Dead of Pill Overdose.” Among those shocked by the report was the author Joyce Carol Oates, who years later would write the Monroe-inspired novel Blonde, and who has come to be one of the most prolific writers in America. “I saw the newspaper headline and felt such a sense of loss,” Oates tells TIME. Then a 25-year-old newlywed, she had moved to Michigan that year with her husband, Raymond J. Smith, to teach at the University of Detroit. “How could such a beautiful, successful and famous young woman kill herself?” she asked, recalling her emotions of that August in 1962.

This was only one of the questions that so many Americans, and people across the world, were asking. Did the 36-year-old icon commit suicide? Did she accidently overdose on chloral hydrate and pentobarbital? Was she murdered? During the research phase for Blonde, published in 2000, Oates read her share of theories and came up with her own conclusion: “I don’t think that she deliberately committed suicide.”

Oates offered justification for this theory in an article she wrote for The Guardian in September 2007, titled “All that Glitters…” In it, she referenced Monroe’s final interview, given to LIFE editor Richard Meryman just weeks before her death. “At the time of this interview for LIFE magazine, Monroe was looking to the future, and not to the past,” Oates wrote. She referred to Monroe’s interview responses as a “monologue of sparkling vivacity and ingenuity.”

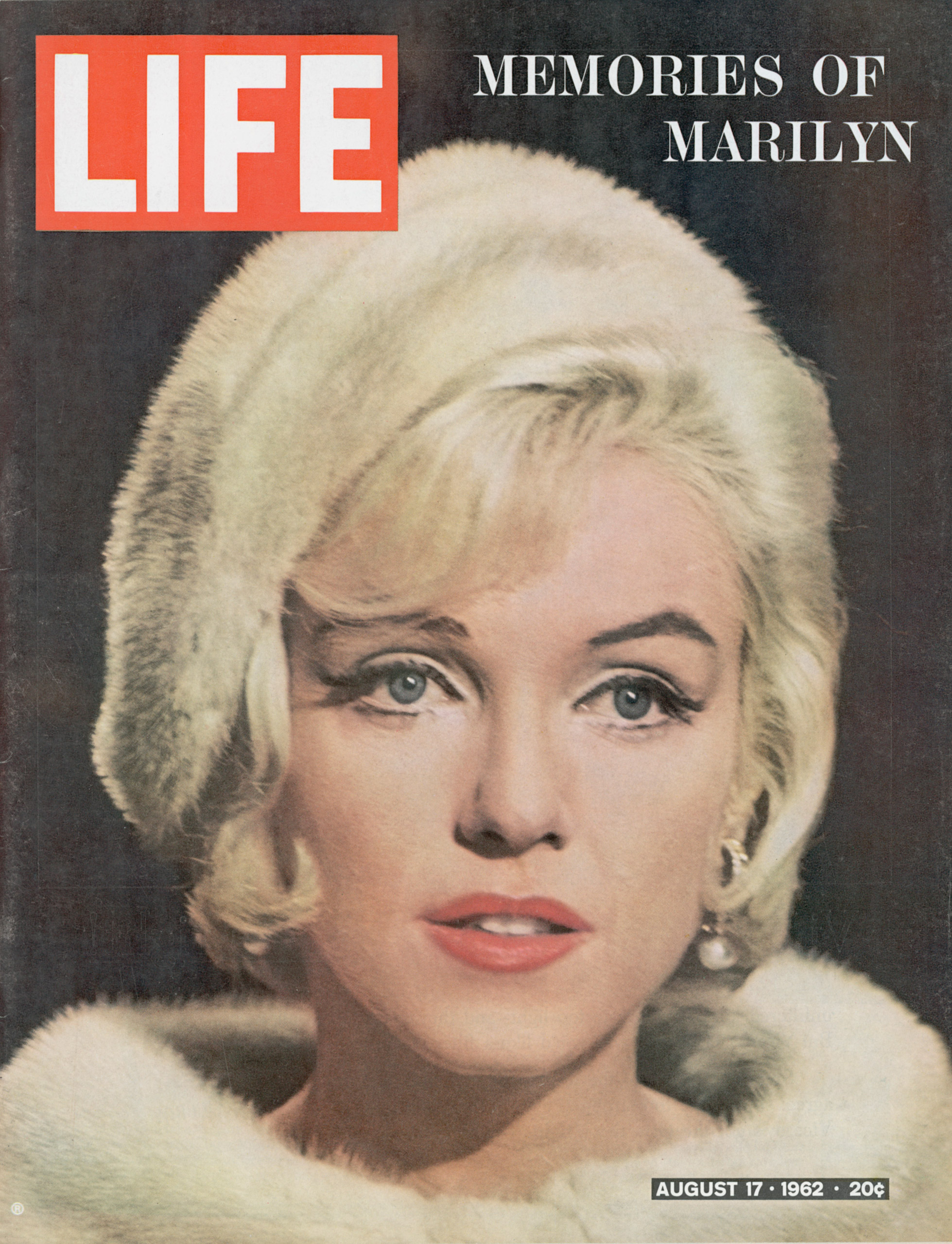

An excitement for life can be heard in Monroe’s voice in the audiotapes Meryman recorded so many years ago. It’s an almost magical feeling to hear her feminine voice, so alive, and her laugh, which sounds like its hiding a million emotions. In the August 17, 1962 issue of LIFE, titled “Memories of Marilyn,” Meryman wrote about his experience interviewing her. “She looked great,” he said. “She had her hair and make-up done, but she was clearly troubled. I saw a roller coaster of moods, intensity, a lot of anger—and sadness as we discussed how her life had been changed by fame.”

This theme is certainly one that Oates tackled in her novel. After all, it was fame that changed the star from Norma Jeane to Marilyn, and it was fame that ultimately destroyed her. Blonde opens with a chilling prologue that foreshadows a future that readers know all too well. Oates then turns her historical and biographical research into a life imagined. Midway through the book, she clues us in on some of Marilyn’s secrets.

“Monroe’s greatest secret was her sense of insecurity and unworthiness,” Oates tells TIME. “She had to be seductive to everyone. It was like a compulsion. A woman who doesn’t especially care what other people think of her, whose sense of self is strong, from within, would not try so hard to please. The very notion of bleaching one’s hair platinum blond, wearing so much makeup and squeezing into tight dresses, would not appeal to many, perhaps most women.”

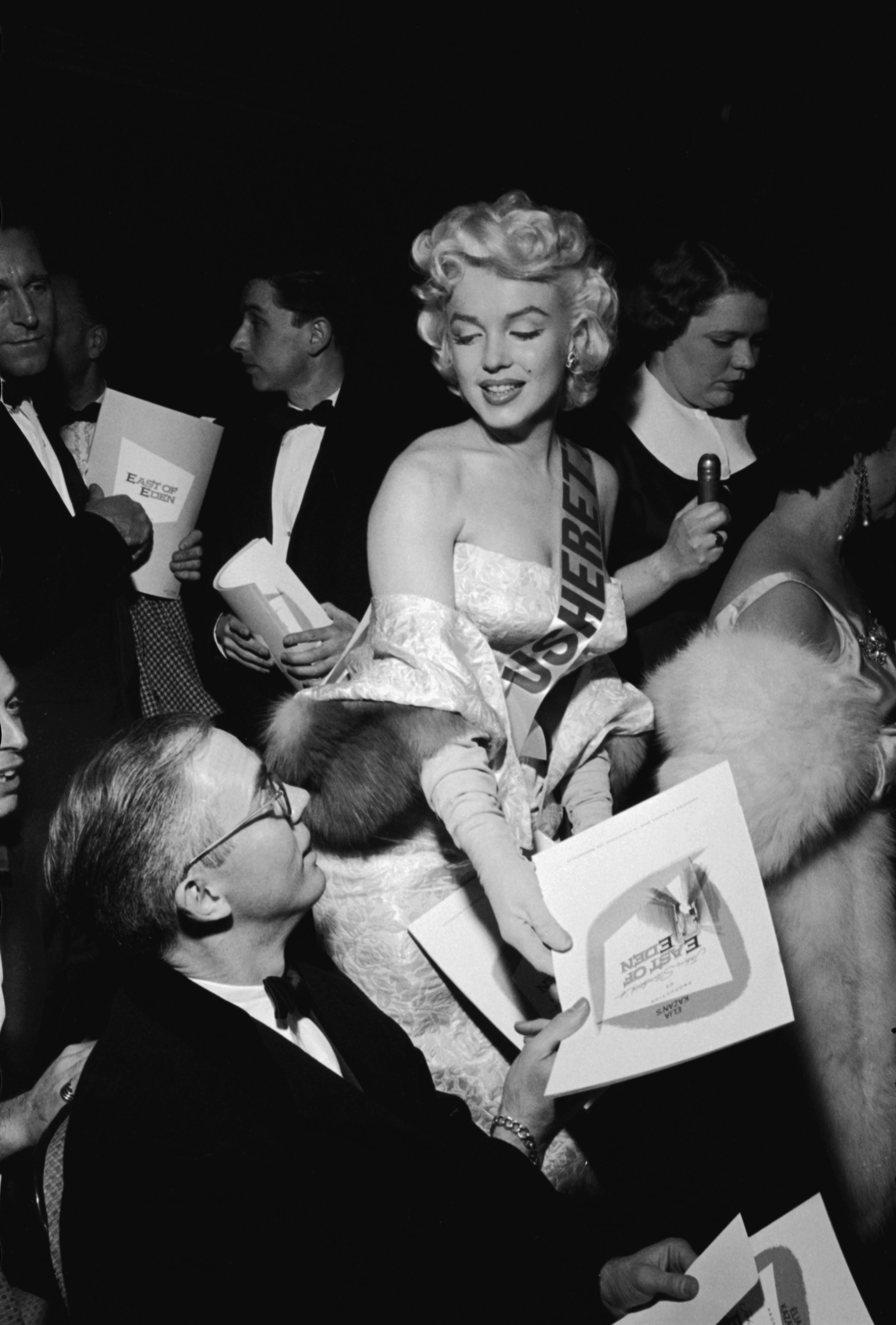

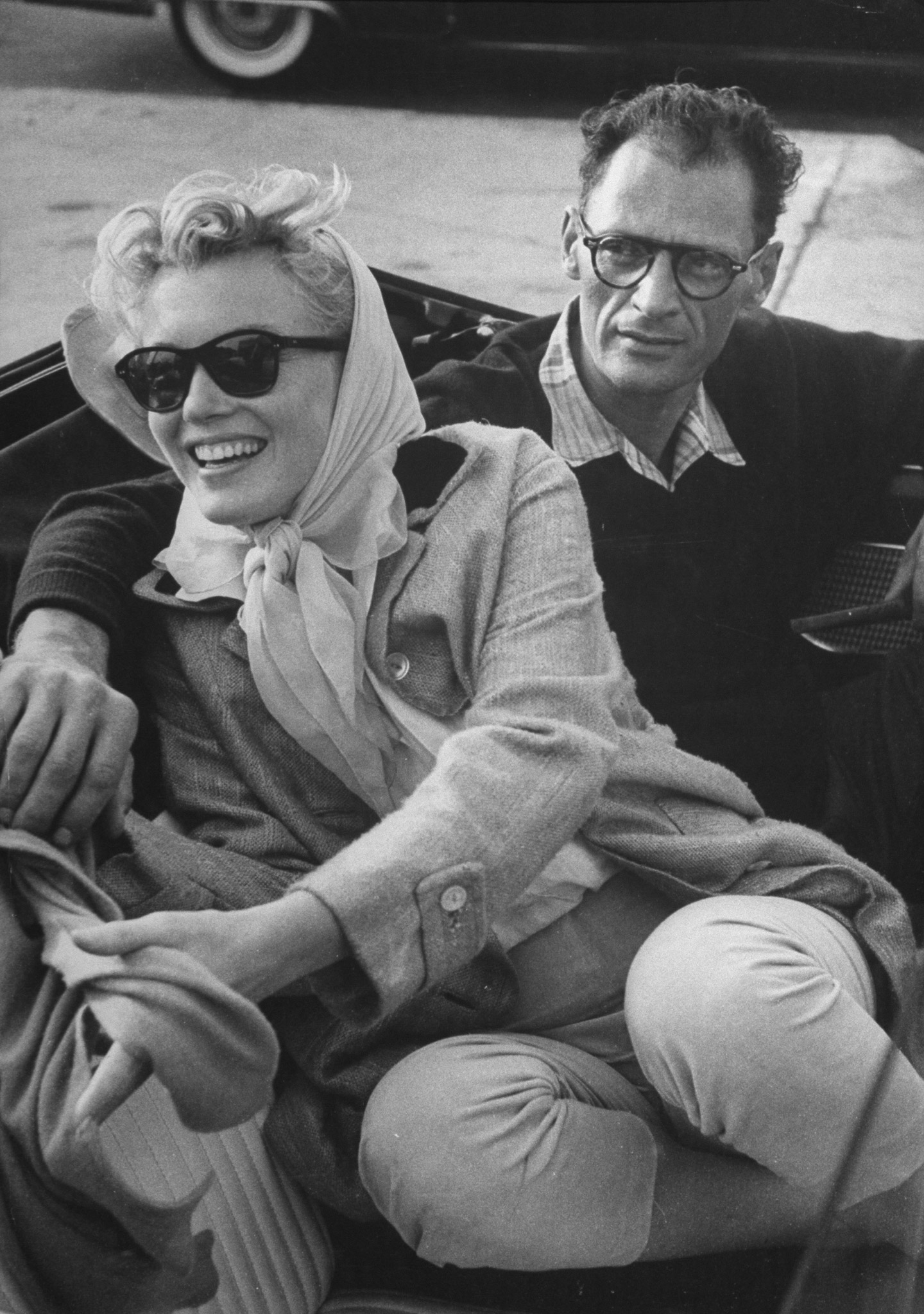

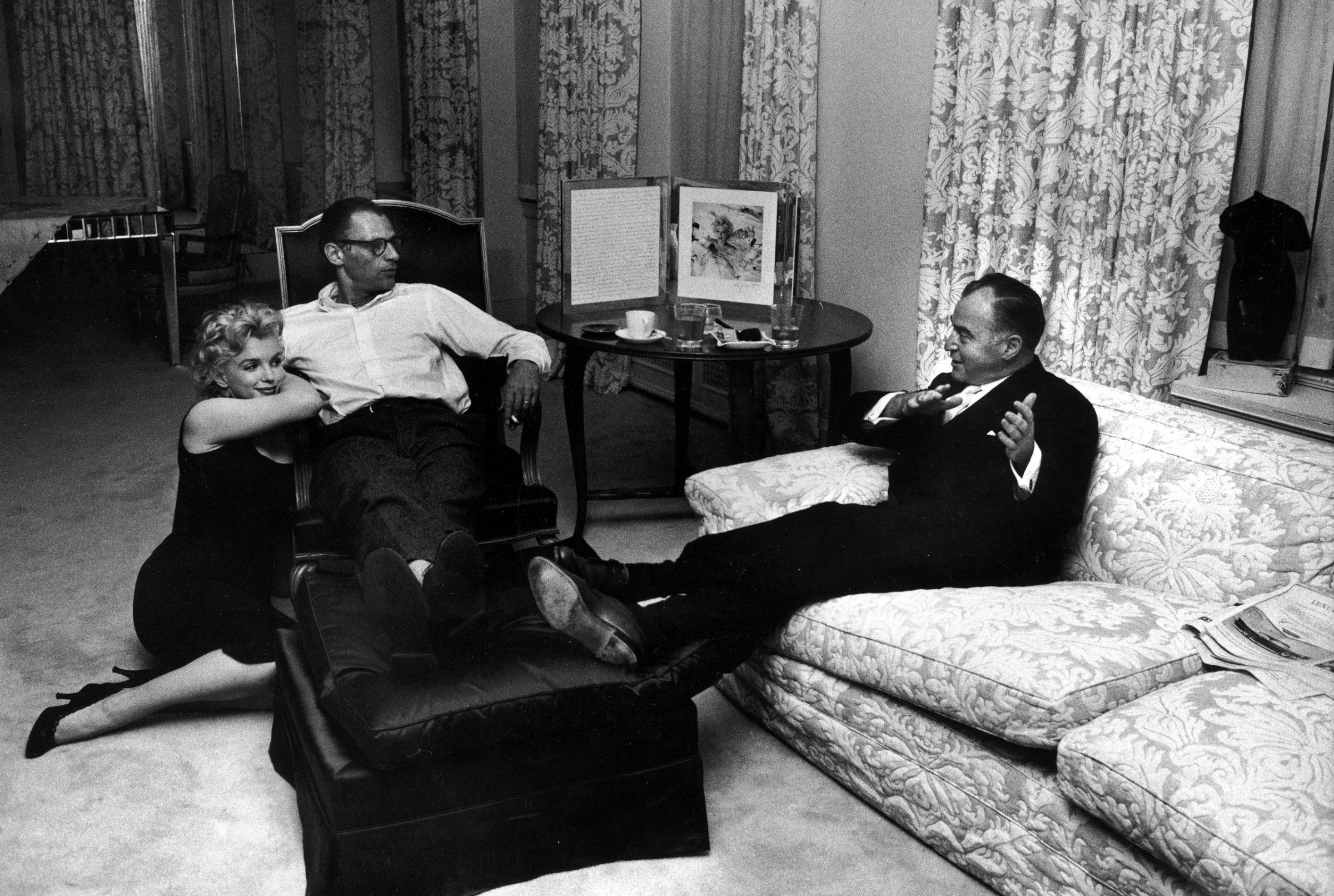

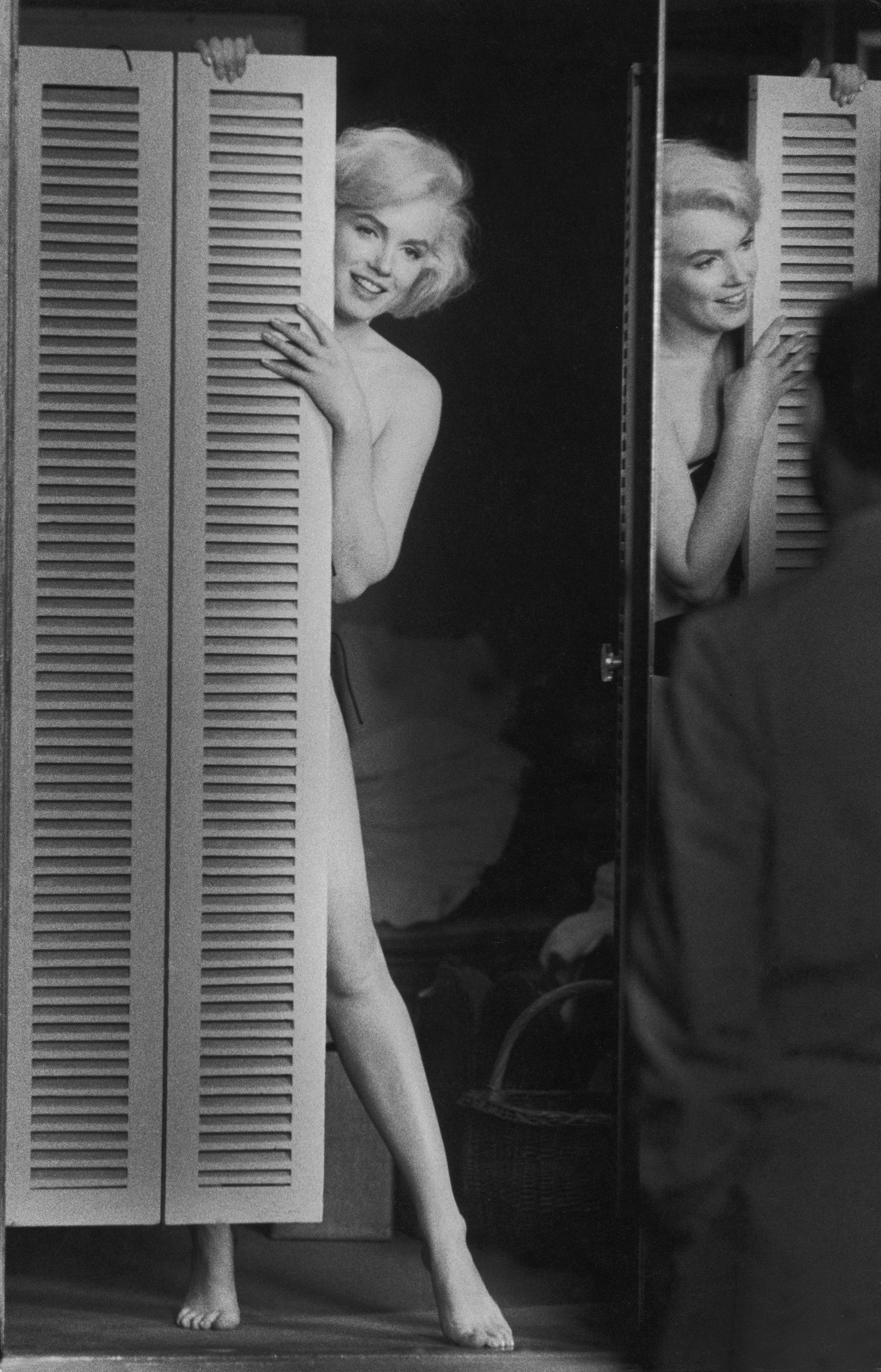

Marilyn Monroe: A Life in Photos

Of all of Oates’ novels, Blonde is not only the longest—it was 1,400 pages before its final edit down to 738—but also one of the most heavily researched. Oates spent more than two years studying Monroe, outlining and writing the novel based on the life of the tortured legend. She describes the book as “a postmodernist/posthumous autobiography narrated by Marilyn Monroe herself. Considering the epic nature of Monroe’s life, as I have imagined it in Blonde,” Oates says, “I think that Monroe is a representative American of a time, a place, a category of being, with whom virtually anyone can identify.”

This has been proven decade after decade as each new generation continues to idolize and reinvent Marilyn. The worlds of art, music, fashion and film continue to prove that imitation is synonymous with flattery. “It is amazing,” Oates said. “Obviously, her great beauty makes her perpetually popular.” But it takes more than just beauty to explain such an enduring fame. “Monroe’s combination of childlike innocence, feminine ‘vulnerability’ and the very tragedy of her life give her an iconic status other actresses can never achieve.”

Looking back on the inspiration for Blonde, Oates admits that she had no interest in writing about Monroe until something happened. “I saw a photo of Norma Jeane Baker taken at about the age of 16, and the image was remarkable: brown hair, a pretty but not beautiful or glamorous face, the very look of an average high school girl of her time. I strongly identified with the girl in the photograph, for whom the glossy image of ‘Marilyn Monroe’ was merely an impersonation.

“In writing Blonde, I’d thought, half-seriously, of Monroe as my Moby Dick, the powerful galvanizing image about which an epic might be constructed, with myriad levels of meaning and significance,” Oates says. “Considered from a feminist perspective, Monroe’s life is exemplary—a tragedy that might have been averted—even as it illuminates some of the paradoxes of the life of the actor: that one must sell oneself, or fail utterly.”

Nikolas Charles is a journalist and photographer based in Los Angeles.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com