The universe is the greatest organic chemistry experiment that’s ever been run. There isn’t a hydrocarbon anywhere that wasn’t born in the Big Bang, cooked up in the stars and blasted back into space where it combined and recombined into the stuff of biology. Living things—as far as we know—may exist only on Earth, but the complex, biotic, raw materials are everywhere. Now, a new paper in Science reports findings from the Philae spacecraft—which bounced down on Comet P67 on Nov. 12—adding a new dimension to that growing body of knowledge.

Comets have always been a good place to go looking for the origins of life in the universe. They are considered the most pristine artifacts of the early solar system—condensing out of the cosmic cloud that formed the sun and the planets, but remaining in the deep freeze of deep space for most of their very long lives, meaning that their chemistry has not changed much over time.

Ground-based telescopes have detected more than 20 species of organic molecules in the coronae—or glowing heads—of comets. Samples of meteorites that have landed on Earth have also shown them to have organic compounds including amino acids. But meteorites are agglomerations of rock that have been altered many times over the eons—not to mention that have been superheated during their plunge through Earth’s atmosphere—meaning that their molecular cargo has been altered and perhaps even contaminated by earth’s biology. Comets have been largely untouched.

The Science paper—one of several from Philae’s various research teams released this week—reports findings from the Cometary Sampling and Composition (COSAC) instrument, which was designed both to sniff the immediate environment of the comet for ambient organics and to drill into the surface to collect and analyze samples. The first half of the experiment went well, but the second half almost came to ruin.

Multiple sniff readings were taken as Philae flew by and approached the comet. According to the plan, once the lander touched down on the comet, an upward-pointing rocket exhaust was supposed to ignite, pressing Philae down onto the surface, and a pair of downward pointing harpoons were supposed to fire, anchoring it in place. Neither system worked.

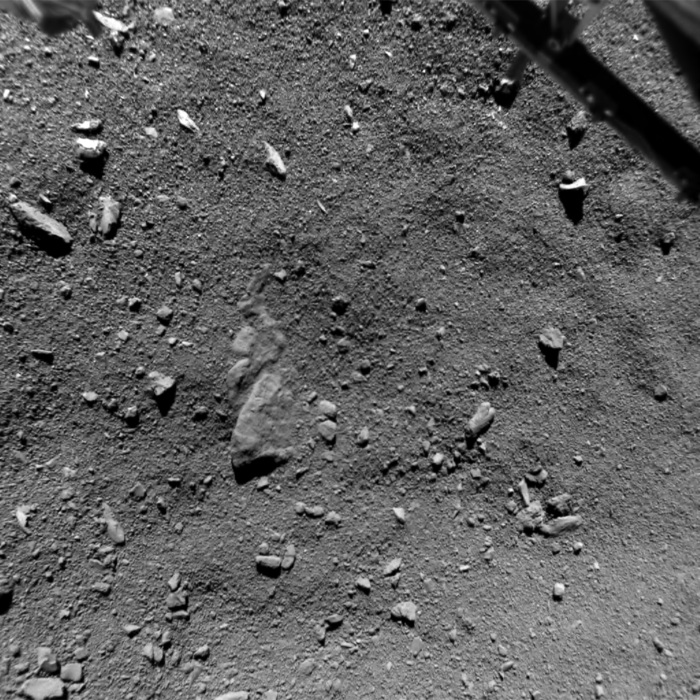

Instead, Philae landed, bounced, and settled back down in an untargeted area with too little sunlight to keep its solar power system running consistently, making the drilling impossible. Fortuitously, however, the impact did cause small clumps of surface material to be drawn into Philae’s pair of .8 in. (2 cm) sample-intake pipes. The temperature inside the pipes was 54° to 59° F (12° to 15° C)—which was plenty warm enough to allow COSAC to do its work.

The instrument detected 16 separate organic compounds of various complexity and with various possible biological uses—four of which had never been seen in a comet before. In earthly organisms, those same molecules play roles in the formation of sugars, amino acids, peptides and nucleotides. Given the right opportunity, they could do the same elsewhere in the cosmos. “The complexity of cometary nucleus chemistry,” the authors of the paper wrote, “impl[ies] that early solar system chemistry fosters the formation of prebiotic material in noticeable concentrations.”

The mission planners hope for more from Philae in the coming months—but whether the little lander can deliver is another matter. The shadowy region in which Philae landed has not brightened up in any lasting way, though a passing slash of sunlight did allow it to stir to life briefly in June. In mid-August, however, P67 will arrive at its closest approach to the sun, and the shadows will surely lift, at least temporarily. If Philae opens its eyes again, it will do so at a very scientifically opportune moment because it is during a comet’s brush with the solar fires that it lights up and becomes most chemically active.

But even if Philae speaks no more, it will have already done its job. It made an improbable journey, landed in an improbable place and has sent home at least some of the scientific knowledge it was built to collect. No matter what it does next, it is destined to remain not just a visitor to a comet, but a permanent part of it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com