Back in the 1960s, we were both rookie engineers working for government organizations in India with just a few years of experience behind us—I worked in electronics and he specialized in aeronautics. Both of us had passed out from the Madras Institute of Technology in southern India, although he was older than me and graduated a few years ahead.

But the first time I met A.P.J. Abdul Kalam—or Kalam, as I always knew him—was in a foreign country: the U.S. I’d gone there in December, 1962, and he followed in March, 1963. We were part of a seven-member team dispatched by Vikram Sarabhai, the father of India’s space program, to train with NASA and learn the art of assembling and launching small rockets for collecting scientific data.

I’d already spent a few months training at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, when Kalam arrived from India. Soon, we were working side by side at NASA’s launch facility in Wallops Island, Virginia. Our lodgings were called the B.O.Q., or the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters, and we’d lunch together at the cafeteria where, because we were both vegetarians, we survived mainly on mashed potatoes, boiled beans, peas, bread and milk. Weekends in Wallops Island were lonely affairs, as the nearest town of Pocomoke City was an hour’s drive away. Thankfully for us, NASA put on a free flight to Washington D.C. for its recruits, so we would head up the to American capital on Friday nights and return to Wallops on the Monday morning shuttle.

It was a memorable experience. I remember one training session where Kalam had to fire a dummy rocket when the countdown hit zero. It was only after half a dozen attempts when he kept firing the rocket either a few seconds too early or too late that the man who went on to become one of India’s best known rocket scientists managed to get it right.

Our American sojourn ended in December, 1963, when we returned to India to help set up a domestic rocket launching facility on the outskirts of Trivandrum, the capital of the southern Indian state of Kerala. It was very different world from NASA. India’s space program was still in its early years and we had to swap our weekend shuttles to Washington for bicycles, our sole mode of transportation in those days.

Quite apart from the change, this presented a practical problem for Kalam: he didn’t know how to ride a bike! He was forced to depend on me or one of the other engineers to ferry him to and from work. When it came to food, if we’d lacked options at the canteen in Wallops Island, in Kerala we had to fend entirely for ourselves: there was no canteen at the nascent launch facility, and we had purchase our lunch at the Trivandrum railway station on the way to work.

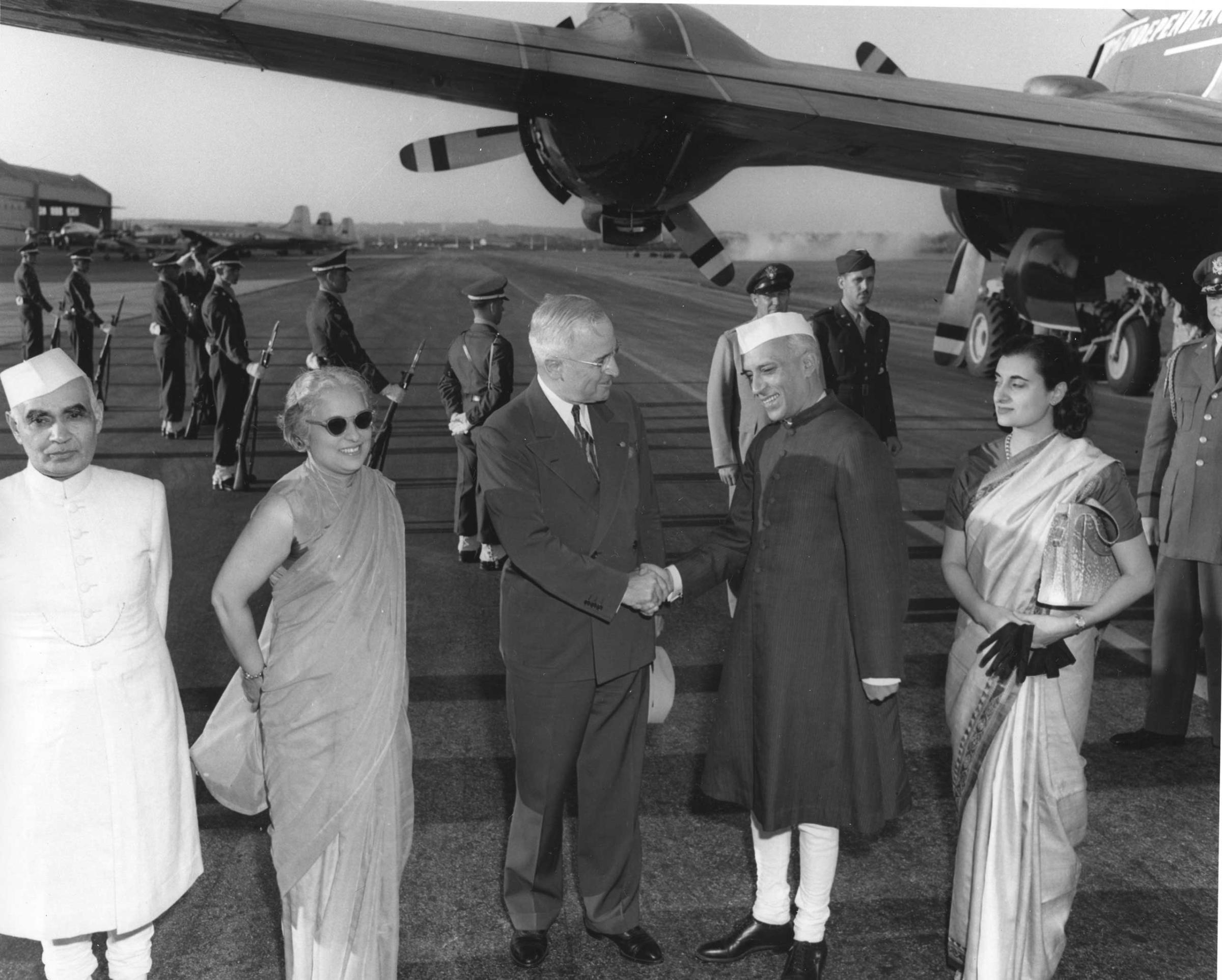

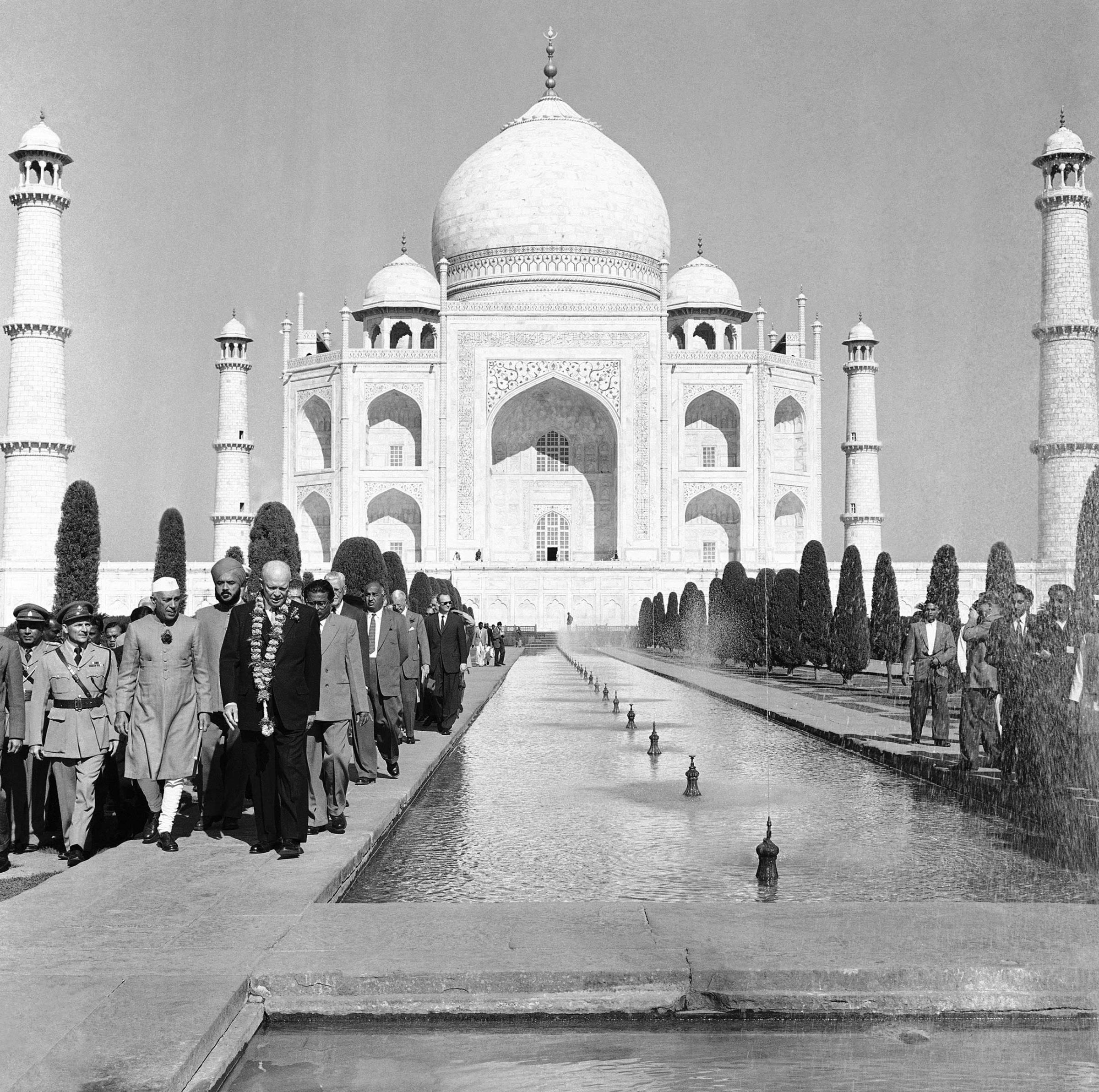

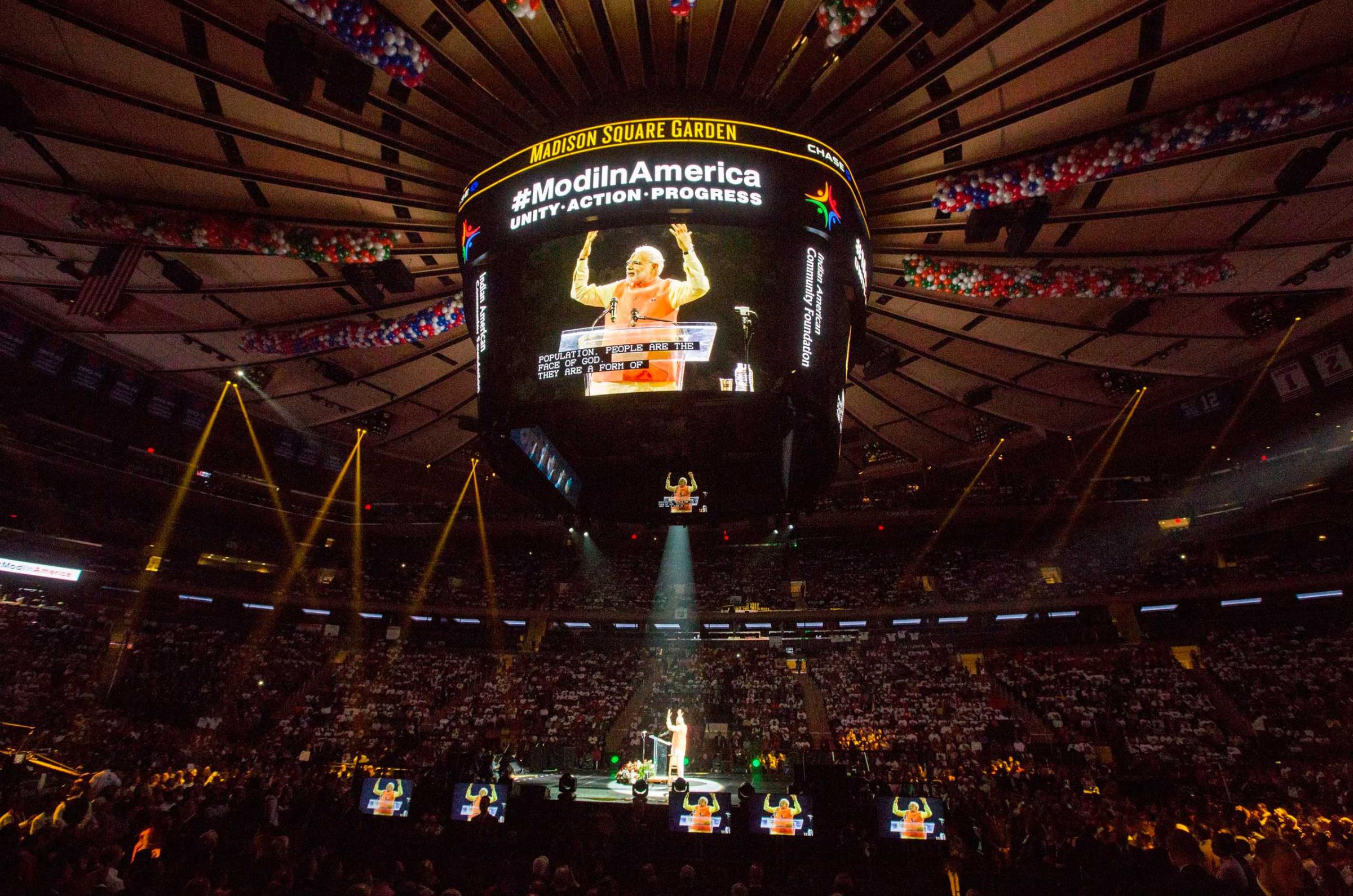

See The History of US—India Relations in 12 Photos

Over the next decade and a half, Kalam and I worked closely on building India’s space program. Kalam eventually became the director of the project to develop the country’s first satellite launch vehicle, a task he pursued with single-minded devotion. He made his team work hard and set the benchmark for them by working twice as hard himself. He had a knack for getting things done and did not let initial failures deter his team. He pushed and pushed until eventually, in 1980, he succeeded with the launch of SLV3, India’s first experimental satellite vehicle which took off from Sriharikota on the country’s southeastern coast.

The same year, Kalam moved to India’s Defense Research and Development Organization and took on the task of building the country’s missiles. He injected a new sense of urgency and energy in the organization, and in 1998, led the team behind the country’s nuclear tests at Pokhran in northwestern India.

His unexpected election in 2002 as India’s President took him to a different plane, transforming him into a statesman and, rightly, a national legend. But he never forgot his early friendships. In 2007, when he was about step down from the presidency, he invited my wife Gita and me to stay with him at Rashtrapati Bhawan, the grand presidential residence in New Delhi.

He never allowed his high office to come in the way of his natural informality, a quality that so endeared to so many across India and the world. One evening during our stay, he invited me and my wife to attend a national awards ceremony that he was hosting in his capacity as President. The ceremony was followed by a reception for the guests, among whom were many dignitaries. Suddenly, Gita and I found that our host had disappeared. I was looking around trying to find him when an aide came up to me and whispered a message from India’s head of state: the President wanted us to leave the other guests behind and join him in the building’s magnificent gardens. It turned out that the great man needed a break from the formality of the awards function and wanted to get some fresh air. For more than an hour, we walked up and down the beautiful gardens, reminiscing about the old days in Trivandrum and the badminton games we used to play at the Rocket Recreation Club.

He returned to his Presidential duties quite recharged.

Aravamudan is a former Director of the Indian Space Research Organization’s Satellite Centre in Bengaluru, India

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com