Somewhere on this hot July day, Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton are thumping each other over jobs and economic policy, but in a cool Dallas office, George W. Bush is sharing a sofa with Bill Clinton to talk about how to handle the 2016 race.

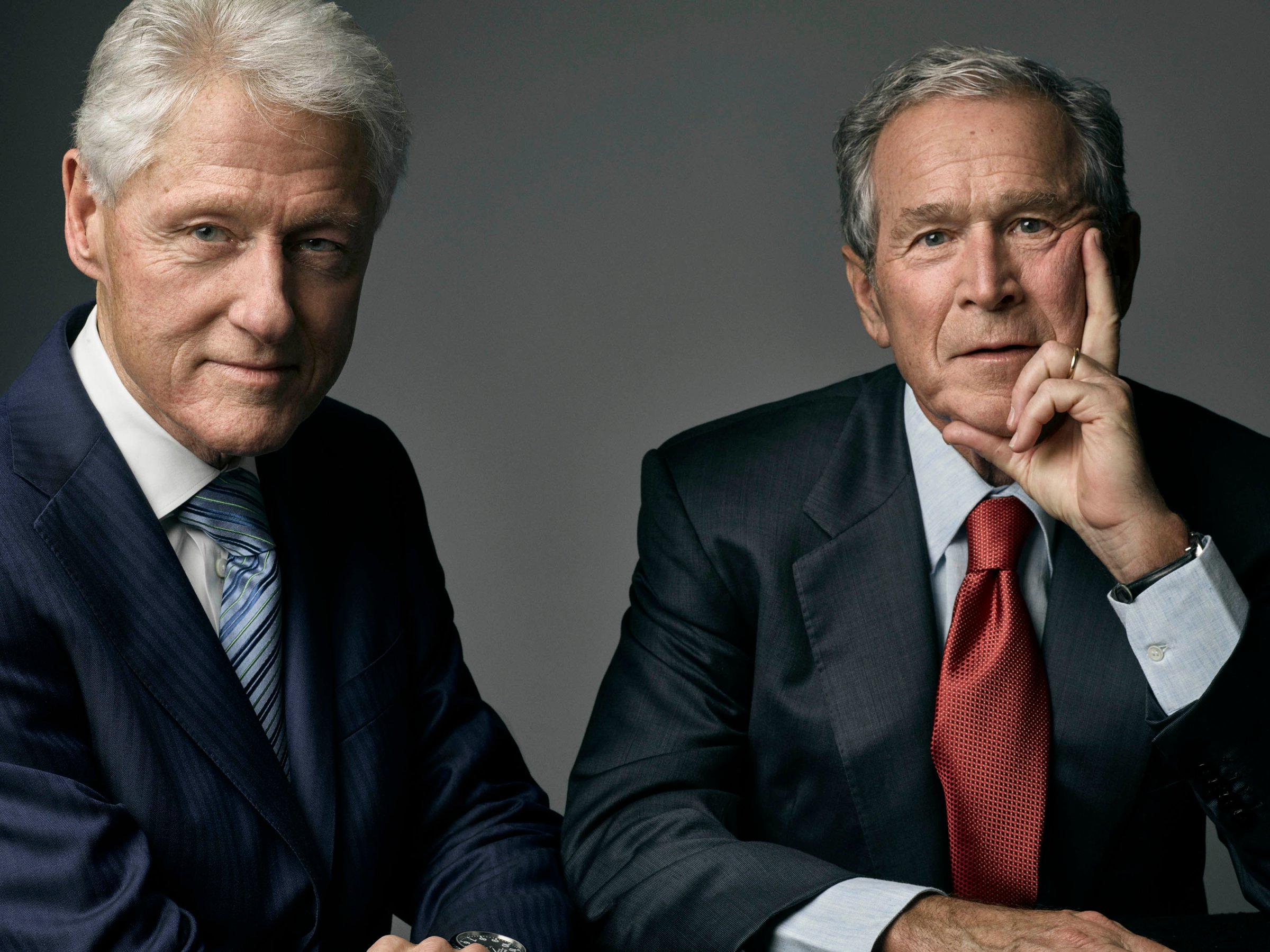

If you watch what they do, not just what they say, this conversation can offer clues to their unprecedented predicament. A populist prairie fire is burning across the campaign trail, on which fevered candidates delight in torching idols. The former Presidents, two Establishment icons, have just appeared together onstage at the Bush Presidential Center, cameras rolling, tweeters tweeting, in a celebration of postpartisan good works. Now they are talking to us, having posed for a portrait, and they have to know that it will make some heads explode to see them together on the cover of a magazine at the same moment when large numbers of voters are asking, Is America really so bereft of plausible candidates that for the ninth time in 10 presidential elections, a Clinton or a Bush may be on the ballot? Why call attention to their unlikely alliance now, as their loved ones prepare for combat that only one, and maybe neither, can win?

They know each other far better than you would expect, two baby boomer Presidents born six weeks apart in 1946 and yet reaching the White House from very different roads and governing from very different compass points. Their connection is visible in the body language, the mutual mockery of each other’s set pieces and shticks, the way they tease and praise and even protect each other in the course of our conversation.

Like the phoenix with its healing powers, a divisive politician resurrected as an elder statesman can be a soothing presence, and the two of them together are even better than one. “I do believe that people yearn to see us both argue and agree,” Clinton says. “And they know in their gut, they gotta know, that all these conflicts just for the sake of conflict are bad for America and not good for the world.” When the two men appear together in public, like at the NCAA basketball finals last year, the crowds cheer. “I think it lifts their spirits,” Bush says. “Most people expect that a Republican and Democrat couldn’t possibly get along in this day and age.”

But there’s more to this duet than harmony. “Look, this is highly complicated,” Clinton says. “People don’t like negative, divisive environments. But they frequently reward them in elections.” So how do these two men behave in the coming months, when politics drives them apart and circumstance binds them together? Clinton and Bush, the Elvis and Prince Hal of American politics, finally have to pull up, step back and stay off the field. Neither one is exactly cut out to be a lion in winter: they are too young, too restless, too sure of their instincts. Clinton tried and failed in the supporting role in 2008, casting a shadow over Hillary’s first presidential campaign. Now he gets a second chance, while Bush gets a first, and you can practically feel them straining to show us how obsolete they are–“We’re like two old war horses being put out to pasture,” says Bush, and over and over they both talk about no longer being “in the arena.” They recognize that each is a more natural retail campaigner than the Bush and Clinton running this time and that they must keep their heads down for the time being. But they will not take their eyes off the game, not for a minute.

“It’s no question it’s ironic that we’re sitting here with a father, two brothers, a husband and a wife,” Bush observes of the past and present White House contenders. But all that experience does give these two a certain feel for how things will unfold, even as the likes of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders suck up media coverage and draw crowds. “I can’t tell you who is going to win, but I can tell you what’s going to happen,” Bush says, and Clinton nods in agreement. “There’s kind of a general pattern. And there will be flashes in the pans, there will be this crisis, there will be the funding thing. There will be all these things that happen, but eventually the person who can best lead their party will be nominated.”

Which is also a bit of a tell. At least for this stage of the journey, the Bush-Clinton interests are aligned: both families carry blessings and baggage; both pack Establishment clout and face an anti-dynastic revolt; both are fueled and funded by big and powerful interests; and both are navigating primary fields that are distorted by magnetic characters on the extremes. So there is a strategic advantage, and a protective cover, to reminding everyone that they know their way around the Oval Office, and know what’s feasible and what’s fantasy, as a field thick with unfamiliar candidates trades competing visions of the future.

These retirees aren’t just rooting for their relatives; at various points they took it upon themselves to urge those relatives into the game. Bush began lobbying Jeb to run last year. To hear Clinton tell it, he began nudging Hillary into the ring 40 years ago.

“I asked her to marry me three times before she said yes,” Clinton recalls, “and the first time I said, ‘I want you to marry me, but you shouldn’t do it.'” He told Hillary that she was the most talented pol of their generation, the most natural leader, with the best command of the issues, and rather than marry him, she should go to Chicago or New York and get into politics.

To which she responded, “Oh my God … I’ll never run for office. I’m too aggressive, and nobody will ever vote for me.”

Clinton pauses, shakes his head. “True story.”

Because it is tempting to dismiss everything politicians do as purely political, it is worth remembering that the Bush-Clinton bond reaches a long, winding ways back. It was by no means obvious that anyone from these two families could get along, especially after the hard-fought 1992 Bush vs. Clinton campaign. The thaw began with a grace note characteristic of George Herbert Walker Bush: a private letter left for Clinton as he took office: “You will be our President when you read this note,” he wrote. “I am rooting hard for you.”

Bush 43 talks about how instructive that moment was: his father gracious in defeat, Clinton humble in victory. The actual family friendship began more than a decade later, when the younger Bush sent Clinton and his father traveling the world together to raise relief funds, first for victims of the 2004 Asian tsunami, then Hurricane Katrina. Soon Clinton became a guest at the Bush home in Kennebunkport, Maine, playing golf, spending the night, hurtling the waves on Bush 41’s powerboat. After Clinton’s heart surgery in 2004, Bush 41 was on the phone checking up on him: What do your doctors say? Are you sore? How much can you exercise? Are you using your treadmill? Clinton escorted Barbara Bush to Betty Ford’s funeral in 2011. It got to the point that George W. began referring to Bill as his “brother from another mother.” Jeb just left it at “Bro.”

“Yeah,” Clinton once mused after an encounter with the whole Bush clan. “The family’s black sheep. Every family’s got one.”

Even Barbara speculated that her husband came to represent the father Clinton never had. But Clinton and her eldest son were hardly a natural fit. George W. seemed a model conformist who followed the pedigreed path of his Greatest Generation father: Andover, Yale, the military and then to West Texas for the oil business. Clinton was an American mutt born into a family of mystery in Arkansas, who surfed the turmoil of the 1960s, didn’t inhale, dodged the draft and missed a lot of law school to work on improbable Democratic campaigns. But which was the real rebel? Clinton was also marching band and Boys Nation, Georgetown and a Rhodes Scholar, elected a governor at the record age of 32. Bush was going nowhere until he was 40, caught in the whirlpool of entitlement and rebellion, wrestling with booze, struggling at business, trying to find his place in the world.

Their paths into politics could hardly have been more different, and their first encounter was rough. In 1999, both George W., as governor of Texas, and Jeb, newly elected in Florida, visited the White House during a governors’ conference. Clinton liked Jeb right away but found George W. downright surly. Still, when Clinton’s aides noted that the Texan seemed particularly uncomfortable, Clinton came to his defense: “Look, the guy’s just being honest. What’s he supposed to do, like me? I defeated his father. He loves his father. It doesn’t bother me–this is a contact sport.” During the 2000 campaign, Clinton watched George W. with growing respect–“compassionate conservatism” is “a genius slogan,” he warned Al Gore’s team–and when George W. paid a visit after he won, Clinton came away from their meeting and a long lunch in the White House residence saying, “It’s a mistake to underestimate him.”

Once out of office, neither man was in a hurry to become a relic from the past. Clinton was 54 when he left office, and Bush was 62; both men had decades to kill and no obvious peaks to conquer. “I’m pretty well convinced that every President goes through a deflationary period after the post-presidency simply because your daily schedule is so different,” Bush says now. “It can’t be nearly as intense.”

Clinton especially dreaded the prospect of life after the White House. “I love this job,” he said in his final weeks in office. “I think I’m getting better at it. I’d run again in a heartbeat if I could.”

He did the next best thing. Hillary had just been elected to the Senate and was working long days paying her dues and establishing her bona fides as a serious lawmaker. Her husband ricocheted around the world, scooping up huge speaking fees, launching his foundation and becoming the most enthusiastic Democratic surrogate of the age. He was out on the hustings for John Kerry just weeks after quadruple bypass surgery. His speech at the 2012 Democratic Convention electrified the delegates and inspired Barack Obama to name him “Secretary of Explaining Stuff.” In tight 2012 election, Bill Clinton is sure winner, ran a headline in the New York Times.

But when it comes to providing the same service for his wife, the imperative changes. His imperfections–the Vesuvian appetites, the roguish residue that still clings to him–do no harm when he’s supporting other Democrats. But Hillary is a special case; her husband was an unhelpful distraction during her failed 2008 presidential campaign. This time around, he has stayed offstage and yet has not quite left. All spring, Hillary found her approval ratings sinking under the weight of questions about their private email server and the doings of the Clinton Foundation. A majority of Americans see her as a strong leader, recent polls indicate; Americans also no longer trust her.

Clinton defends the model of their foundation, which builds coalitions to address challenges like maternal health, AIDS, and development and sustainability. If his post-presidency has a signature, it has been forging partnerships between private businesses and government officials to break down barriers to change. At a time when the treatments were prohibitively expensive, Clinton worked with drug companies and foreign governments to make HIV/AIDS therapies cheaper and more plentiful in African countries. He applied the same approach at home, persuading state education officials and food executives to revise school lunch menus to combat obesity. “I think it’s crazy to keep all of these efforts siloed,” he says. “As long as you have total and full disclosure, and people can evaluate the impact of what you’ve done and the impact of the decisions you’ve made and how to do it, it’s still the right way to go.” Clinton continues, “Now I’ve been, as you know, criticized for it the last few months, but I still think we’re right.” The foundation says it has disclosed the names and aggregate amounts of most of its 300,000-plus donors since its founding in 2001; the identities of donors to a Canadian partnership with the foundation, however, remain secret.

Clinton maintains a relentless pace–and it shows. Since mid-June, he has been to Hanoi to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the normalization of U.S.-Vietnam relations, Memphis for a funeral of a civil rights leader, Philadelphia for the NAACP convention and London for a conference on “inclusive capitalism,” and he made an appearance on The Daily Show in New York City before flying down to Dallas. The next day, when Bush was heading to his ranch, Clinton would fly to Bosnia for the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. He is noticeably thinner now, his voice hoarse and often cracking, but he says he is fine. And even at the end of a long interview, he keeps talking, expressing sympathy for Obama, who faces global challenges from Greece to Iran. “In a time when a lot of stuff’s happening,” he noted, “almost all of your foreign policy decisions are likely to be unpopular.”

Bush left office with an approval rating roughly half as high as Clinton’s, and polls still rank him as the less popular of the two. But this summer, for the first time, more Americans like Bush than dislike him, according to a June CNN/ORC poll. And aides say he is more certain than ever that history will treat him well. Although a majority of Americans, and even Republican candidates, now call the Iraq War a mistake–an ill-considered kicking of a Middle East hornets’ nest–the loosed furies of ISIS may restore some sympathy for Bush, as Obama deals with the threat of radical Islamic terrorism. Bush aides are careful never to say this on the record; they prefer to say he is “more comfortable now.” Bush will say only that “I feel a sense of liberation by being out of the process. I feel no need whatsoever to try to vindicate my decisions by attacking somebody else, and I’m very content with that decision.”

Bush has made a quiet crusade out of helping wounded veterans return to private life, sponsoring a 62-mile (100 km) bike ride each summer and a golf tournament each fall–though that commitment was tarnished this summer when ABC News revealed that he accepted a $100,000 speaking fee in 2012 from a veterans’ group. But he was comfortable enough with history’s judgment to actively, if quietly, urge Jeb to jump into the Republican race last summer. Given the near certainty of Hillary’s bid, his logic was mathematical: “What difference does it make,” he said at the time, “if the order is Bush/Clinton/Bush/Obama/Clinton or it is Bush/Clinton/Bush/Obama/Bush?” Even if the nation longed for a fresh face, the fantastic plot twist of 2016 was that someone named Bush still stood a chance. To Bush 43, at least, the downside of one dynasty canceled the downside of the other.

These days, Bush seems “unplugged,” as one friend puts it. “I’m very engaged in things that I’m interested in,” he says. He and his wife Laura have made five trips to Africa, where they have promoted the testing and treatment of cervical and breast cancer in five nations–work that built upon the anti-AIDS work Bush pioneered while in office. For the first time this year, Bush, Clinton and the libraries of LBJ and Bush 41 created a six-month leadership-training program for 60 mid-career private and public officials, whose graduation is what brought the two Presidents together in Dallas.

And though he has been teased about it, “painting has helped me a lot,” Bush says. This counts as serious therapy for restless former statesmen: Churchill painted, as did Eisenhower and even Jimmy Carter. Aides say Bush can break into discussion about “light values” at any moment, and his easels and paints have taken over a weight room at the family compound in Maine. He has done series on dogs and leaders and, more recently, his granddaughter, though he admits that efforts to paint his wife have not been successful. Asked if he has tried painting Clinton, Bush pretends to be serious: “I’ve tried and tried and tried.” Then he confesses, “No, I haven’t. I don’t want to ruin friendships.”

“He can’t get my bulbous nose right,” Clinton deadpans.

The minute they met up in Dallas, the ribbing began, from joking about going to prom together as they posed for photos for this story to tussling onstage at the ceremony for the scholars. They know each other’s moves well enough to pull back the curtain. At one point, Bush found himself talking about how important it is for a President to “find people who are capable of fighting through all the trappings of power and giving you good advice … and the environment is such that the sycophants aren’t allowed in.”

Then, almost reflexively, he stops himself. “I don’t know if that makes any sense. They told me to use some big words.”

At this, Clinton rolls his eyes, throws back his head and laughs. “This is the point where I reach in my back pocket to make sure my billfold’s still there,” he says, for he long ago concluded that Bush’s good-ol’-boy act is a means to an end.

And now Bush is laughing too as Clinton mocks him. “I don’t know any big words,” Clinton apes. “I’m just a poor, itinerant portrait artist.”

So later we ask them, do they have any advice for Obama, 15 years their junior, as he prepares for his own prexit?

“I can’t speak to him about that,” Bush says. “I can tell you what makes me happy. He’s just going to have to figure it out himself, don’t you think, Bill?”

“I think Obama will do great,” Clinton says. “I think he’ll have a good, successful post-presidency.”

Which just leaves the small matter of who will be taking his place.

It will be fun to watch the two alpha dogs of American politics try to muzzle themselves and sit on their paws. Certainly, their namesakes are doing their best to pretend that they don’t exist: Jeb and Hillary officially walked on the campaign stage 48 hours apart in the middle of June, beneath logos that omitted their last names. A CNN/ORC poll found that the public was equally split, 39% to 39%, on whether Hillary’s being the wife of a former President made voters more or less likely to vote for her. For Jeb, the challenge is clearer. Asked whether being the son and brother of Presidents made a difference, 56% said it made them less likely to vote for him, while only 27% said that made it more likely. Both Hillary and Jeb will benefit from vast family fundraising networks; the Wall Street Journal reported that at least 136 “top tier” donors who gave to George W. gave to Jeb in the first 15 days of his campaign in June.

Earlier this year at a private fundraiser, George W. reportedly called Hillary formidable but beatable, and you get the sense that his opinion hasn’t changed. “You know, I’m pulling for Jeb as hard as I can pull for him,” Bush says. His brother is “plenty smart and plenty capable, and if he needs my help, he’ll call me. Otherwise I’m on the sidelines, and happily so.”

But he understands that, as a personal matter, Jeb’s quest could create painful moments. “All these campaigns have a sting to them if one of your loved ones is in the arena,” Bush says. “It’s just the nature of the deal.” Bush was famously allergic to introspection as President, but he knows this much about the coming months: “I’m sure there will be moments where somebody says something about Jeb or somebody writes something about Jeb that will sting. I shouldn’t say I’m used to it, but the emotions I felt when our dad was criticized really got me for a while … I think I’ll feel the same thing about Jeb. It’ll be interesting to see how affected I become.”

For Clinton, the challenge is different. A brother has a ringside seat; a spouse is actually inside the ropes with the blood, sweat and fists. Bush’s life won’t change much if his brother is elected; Clinton will invent a whole new role if Hillary makes him America’s first former President turned First Man.

Clinton stood proudly but silently beside Hillary at her first major rally in New York–set, not incidentally, on Roosevelt Island, not Clinton Street. It was her mother Dorothy Rodham whom Hillary extolled as a role model. “It was a little bit different for us, because we live together,” Clinton says of ordering his steps in the months to come. And because, at least for the moment, Hillary’s primary challenge looks easier than Jeb’s, Clinton has to be prepared. He is clearly trying to get the Clinton Foundation on a footing that would allow their daughter Chelsea to take it over, so he can disappear “if next year I have to take an extended leave.”

The 2016 race, Clinton says, is going to be about the economy and how to make it bigger and broader. But just as he starts to get going on the topic with his old intensity, you can hear him hitting the brakes, as if he were saying to himself, “It’s not your turn.” Says Clinton: “I think the debate could become fresh for Americans if it’s really about … how do you create broadly shared prosperity all over the world? I think it’s going to be interesting.” But now, he says, “I think most of my role will be giving advice if I’m asked for it. And I try not to even offer it at home unless I’m asked. But she’s been pretty good about asking every now and then.”

Before the conversation ends, both Clinton and Bush have a few things to say about the shallow state of political commentary, how silly the silly season has become and how impossible it will be to hold the attention of voters. Both men lived through–and helped intensify–the era of instant criticism that attends and afflicts those who would replace them. Both are clearly relieved to be out of it.

They are busy modeling their new cloaks of invisibility. It is the paradox of dynasties in American politics that, in order to endure, you have to deny that you are part of one. So instead of using the D word, we ask: Is American politics just another kind of family business?

“I don’t think it’s a family business,” Bush replies. “That means when I was raised, it was, ‘O.K., little boy, I want you to start studying the political issues so that when you get old enough we’ll be ready to chuck you into the arena.’ That’s not the way it worked. The way it worked was, in my case, I got married, I had to make a living, and no question I was interested in politics, primarily because I admired my dad so much.”

Bush latches on to a quality that both men share and recognize in one another. “I became very fascinated by people, how they think and how they react. I like people, like Bill. I would say we’re both good retail campaigners, and to be a good retail campaigner you’ve got to like people, you’ve got to be interested in them … But the idea of a family business, I think, is too cynical.” He adds, “There are no gimmes in the American political system, so business, I think, is too harsh a word.”

Maybe instead it’s a calling?

“Well, yeah, in the sense that serving others is a calling,” Bush says. “I think Jeb feels the same way, that the best way to serve others is through the political process.”

Bush turns to Clinton. “You think it’s a family business?”

“No,” Clinton replies. “I think that people tend to be interested in the same things, though, and if you are lucky enough to have interest and talent and the willingness to work hard, you may get a disproportionate representation.” Which may be Clinton’s way of saying, Yes, politics is a family affair, and by the way, may the best family win.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com