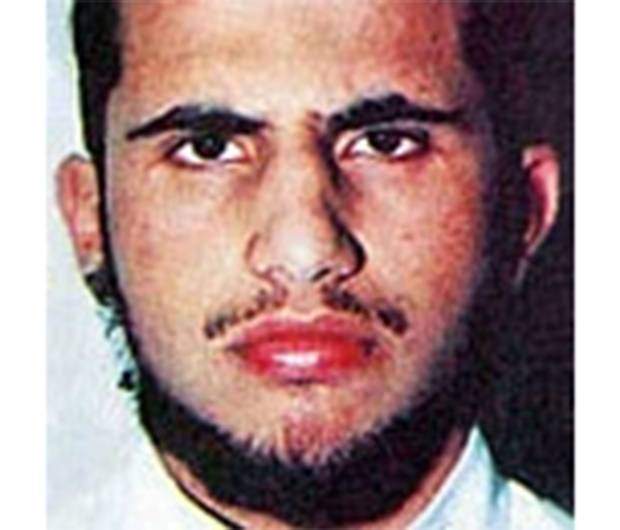

“If you target Americans,” President Obama warned terrorists during a speech to the Veterans of Foreign Wars on Tuesday, “you will find no safe haven.” Like an explosive exclamation point, the Pentagon confirmed his pledge hours later, announcing that the U.S. military had killed Muhsin al-Fadhli. Thirteen years earlier, the military said, al-Fadhli played a role in the killing of Marine Lance Corporal Antonio “Tony” Sledd.

It was a lengthy wait, and one that may not bring much comfort to Sledd’s family, who complained he never should have died. But the nature of both killings—and the 4,656 days between them—highlights the unusual complications of a religion-fueled war, where traditional norms of warfare often don’t apply.

Sledd was 20 when he died on Oct. 8, 2002, on Faylaka Island, 20 miles east of Kuwait City in the Persian Gulf. He was killed by a pair of Kuwaitis who had infiltrated a U.S. military training exercise in a white truck and opened fire with their AK-47s.

Sledd’s killing has been described by some as the first American casualty of the second Iraq war. While the invasion was five months away, the Marines were practicing urban warfare on the island, readying for the conflict. The killers gunned down Sledd during a break in the training as he readied a makeshift baseball diamond, echoing the sport he played as a youngster in Hillsborough, Fla.

As bizarre as Sheed’s death was, so was the way the U.S. military killed al-Fadhli, 34: with a drone strike July 8 as he traveled by vehicle near Sarmada in northwestern Syria. It took the Pentagon two weeks to confirm his death. “Al-Fadhli was the leader of a network of veteran al-Qaeda operatives, sometimes called the Khorasan Group, who are plotting external attacks against the United States and our allies,” Navy Captain Jeff Davis, a Pentagon spokesman, said in a statement. He added that al-Fadhli also was “involved” in the 2002 attack “against U.S. Marines on Faylaka Island in Kuwait.”

While the Pentagon said al-Fadhli was “among the few” al Qaeda leaders who “received advance notification” of the 9/11 attacks before they happened, the attack on the Marines on Faylaka Island was the only U.S. death the Pentagon cited in the statement detailing al-Fadhli’s killing in which he was alleged to have played an active role.

Sledd was one of about 150 Marines on the island, from the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit aboard a flotilla led by the amphibious assault ship USS Belleau Wood.

The day before the attack, some leathernecks had spotted the two Kuwaitis who they believed killed Sledd and wounded a second Marine. “We weren’t expecting trouble,” one Marine recalled. “I thought they were probably just curious about Marines.”

The next day, the Marines began their training using blanks, with armed sentries standing guard. But when there was a break in the action, Sledd’s platoon turned in their live ammo, according to Marines who were there. After shooting Sledd and wounding Lance Corporal George Simpson, 21, of Dayton, Ohio, Anas al-Kandari, 21, and his cousin, Jassem al-Hajiri, 26, suspected Islamic militants, were killed by a second group of Marines after firing on them.

An Army medevac helicopter picked up Sledd, who had been shot in the chin and stomach, within 10 minutes. “Marines can be as tough as woodpecker lips, and I thought he was going to live,” his first sergeant said after seeing him just before the rescue chopper lifted off, bound for a military hospital in Kuwait City. “He squeezed my hand as hard as any healthy Marine could do.” But he died during surgery.

“Till this day I don’t think I did enough and I want to apologize to Sledd’s family and friends,” a Marine comrade posted on a memorial website in 2009, more than six years after his death. “It was my job to bring him back and I didn’t, I’m so sorry!”

Sledd’s parents were upset that their son died amid armed Marines in an allied nation. “There’s no way civilians should have been in that area where Tony was,” Tom Sledd told the Orlando Sentinel shortly after his son’s death. “They should have been challenged and shot before they got close enough to shoot Tony…he was a good boy. He didn’t have to die so young.” His mother, Norma, agreed. “Security perimeters were not set up, and that is why he lost his life,” she said. “They murdered my son.”

Ten months later, a corps probe agreed that proper security would most likely have prevented the young Marine’s death. Sledd’s parents couldn’t be reached for comment on the Pentagon announcement of al-Fadhli’s death.

Sledd, whose fraternal twin, Mike, was serving in the corps when his brother died, sent his mother an email shortly before the attack. “Tell everyone I love them and we are doing the best we can to protect y’all’s country,” it read. “Love, Big T.”

Earlier this month, his government did its best to return the favor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com