Growing up, my house was filled with political leaders, spiritual leaders, social justice leaders, countless friends of my four brothers and I, and people with intellectual disabilities. It was definitely an eclectic mix, and I must admit that initially no one seemed quite sure what to make of this, including me. But soon, hesitation gave way to interactions, which began to give way to open-minded (and open-hearted) conversations between groups of people who initially seemed to have little in common.

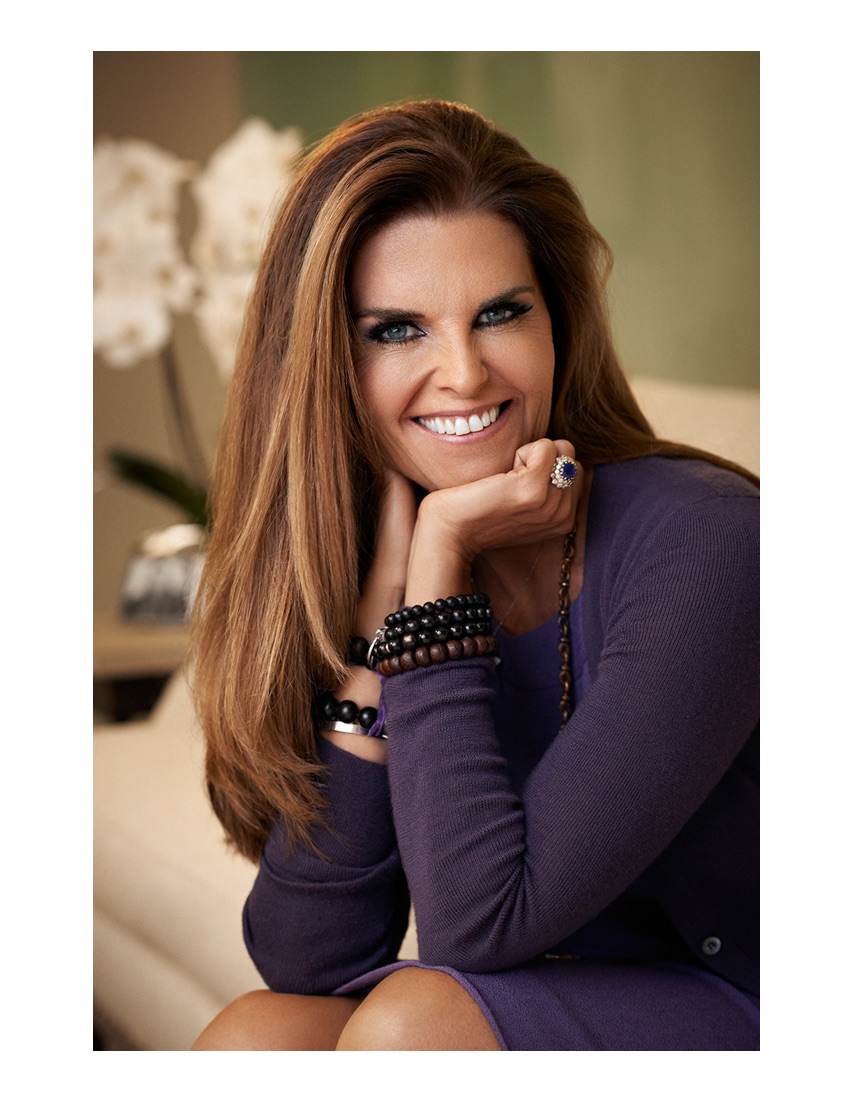

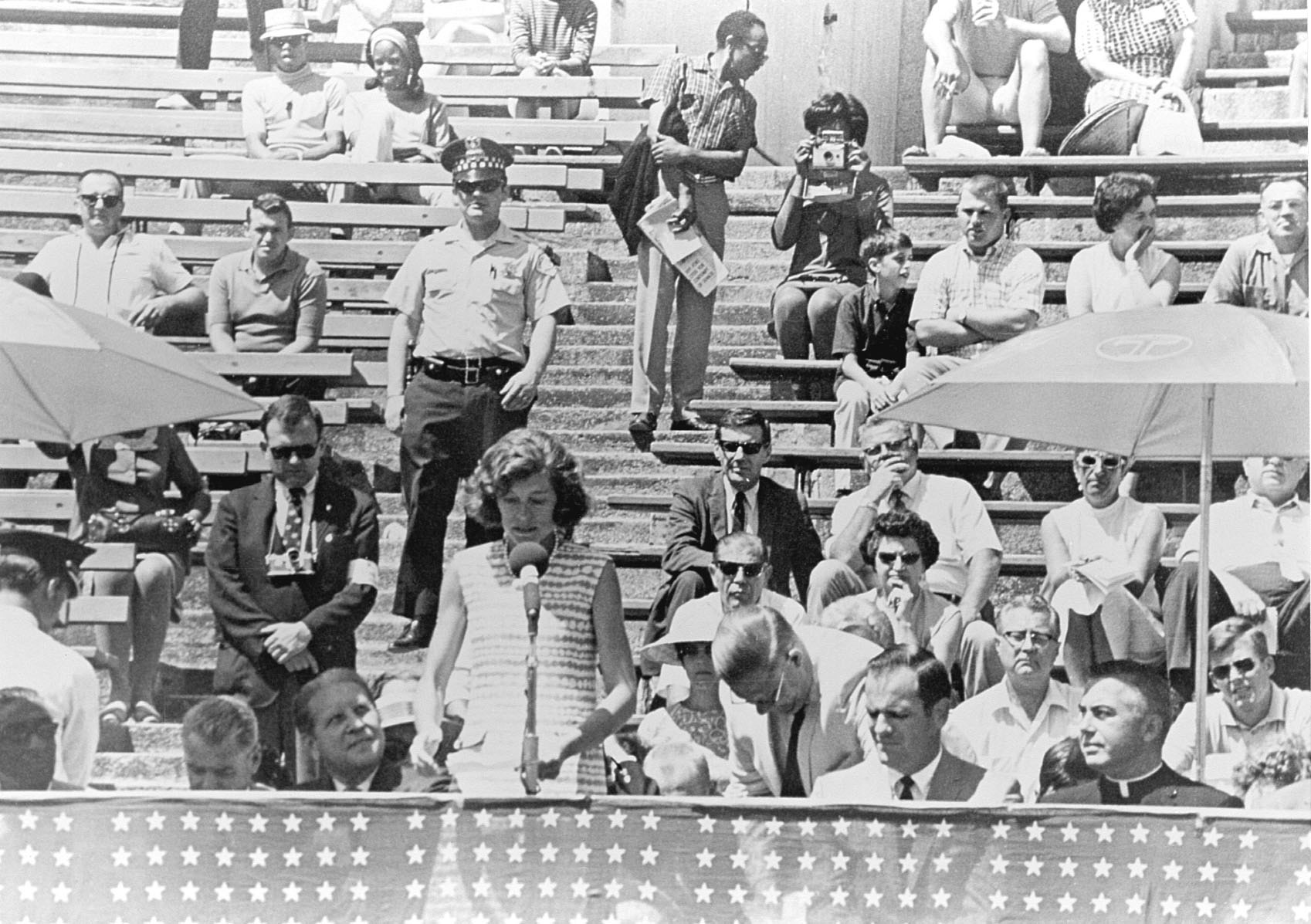

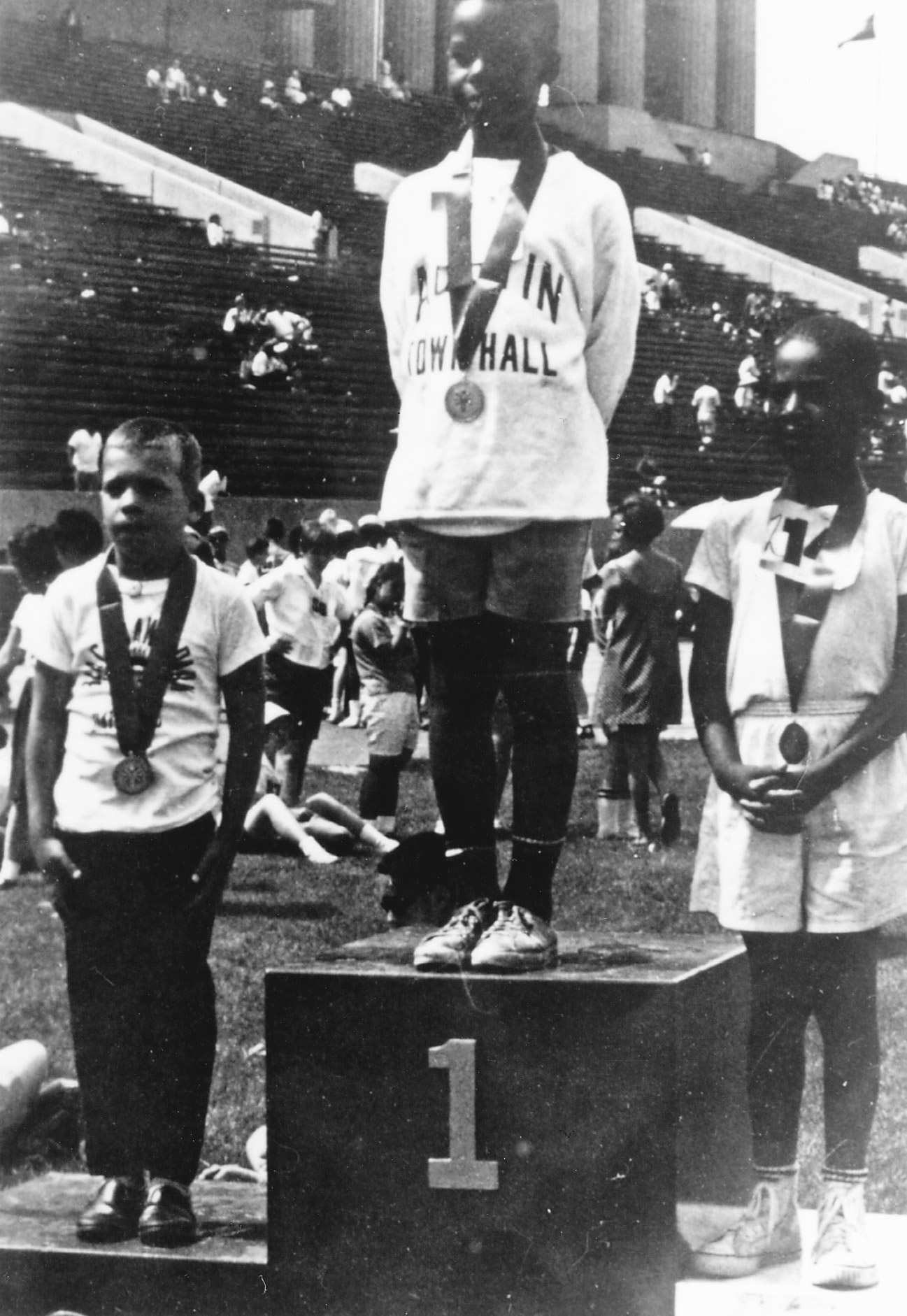

Thanks to my mother Eunice Kennedy Shriver’s fierce will, enormous vision, and relentless drive, I grew up believing that people with intellectual disabilities—like her sister Rosemary—were not to be feared or warehoused in institutions. I grew up hearing how these people and their families struggled in isolation. I grew up seeing my mother fight for their civil rights—their rights to an education and their human rights to be seen as valuable and important members of our larger global family. I grew up being told, and being shown, that people with intellectual disabilities were capable and able beings who could not only out-perform my siblings and our friends in athletic competition, but could also teach us lessons in family unity, perseverance, courage, and love.

We have come a long way since my mother’s backyard summer camp evolved into the global movement now known as the Special Olympics. But we still have a long way to go. In the just-published Shriver Report Snapshot: Insight into Intellectual Disabilities in the 21st Century, we learned that while the institutions that warehoused people in the 60s and 70s have closed, nearly half of our country’s adult population still say they don’t know a single person with intellectual disability, and a stunning 1 in 5 don’t even know what an intellectual disability is.

As the U.S. prepares to welcome 6,500 athletes and coaches from 165 countries to Los Angeles this weekend to compete in 25 sports at the Special Olympics World Games and celebrate the 25th anniversary of the historic Americans with Disabilities Act, these facts should ignite us all to “Change the Game.”

How do we do that? Well, the Shriver Report Snapshot reveals that the more than half of Americans who do know someone with intellectual disability, who have had a personal experience, can show us the way. They report progressive attitudes and high levels of empathy when it comes to educating people with intellectual disabilities, when it comes to where they should work, and whom they should marry and date. They are more likely to understand the hurtful implications the R-word (retard) has on this community, their family members and their supporters.

These game changers, primarily millennial women, can lead the more than 40% of the country who said they do not personally know a person with an intellectual disability. This nearly half of our country continues to hold onto outdated views laced with fear and misunderstanding.

I believe this is possible because we have witnessed the remarkable speed with which Americans can change long-held attitudes. Most recently, we’ve seen our society’s rapid evolution regarding marriage equality, and we are seeing it now on the subject of transgender rights. We are a nation that can and does change, and we owe nothing less to our citizens with intellectual disabilities.

I believe we will change as a nation when we find out that just more than 1 in 10 Americans say they count a person with intellectual disabilities as a friend. I believe we will change as a nation when we find out 22% of Americans think people with intellectual disability should not be allowed to vote. I believe we will change as a nation when you hear the stories of so many families who say their child with intellectual disabilities is not welcome on their school sports teams. I believe we will change our language when we hear from people like Eddie Barbanell who talks openly of the devastating and humiliating impact the R-Word has. I believe we will change when we hear the countless stories families around the globe tell of the positive influence their child with intellectual disabilities has had on the family unit.

I think this is especially important because 91% of Americans think some, most, or all people would terminate a pregnancy or give a child up for adoption if told they would have an intellectual disability. This is a decision based on fear of being able to handle the situation emotionally, financially and physically. Fear and misunderstanding remain.

So this week, let these Special Olympics World Games serve as a catalyst for change. Gather your family and turn on ESPN, which is devoting its prime-time television space to these remarkable athletes and their stories—stories that are no less powerful and inspiring than the stories that come out of the Olympics every four years.

Have a dialogue with your children about inclusion, acceptance, and language. If you live in LA, come and watch. Reach out to someone you know with an intellectual disability or a family with a child with intellectual disabilities. If you don’t know someone, as my mother would say, go find someone. They’re here. They probably live near you. If you pass a person on the street with intellectual disabilities, instead of averting your glance and walking by, stop. Smile. Start a conversation. Share what you learn. These simple actions will begin to change the game.

Then, the next time we take the pulse of this country, I’m confident those excluding and isolating numbers will have shifted. I’m confident that we will be a better, stronger and more compassionate country if we include and value everyone in it. #LetsChangetheGame

See Photos From the First Special Olympics

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com