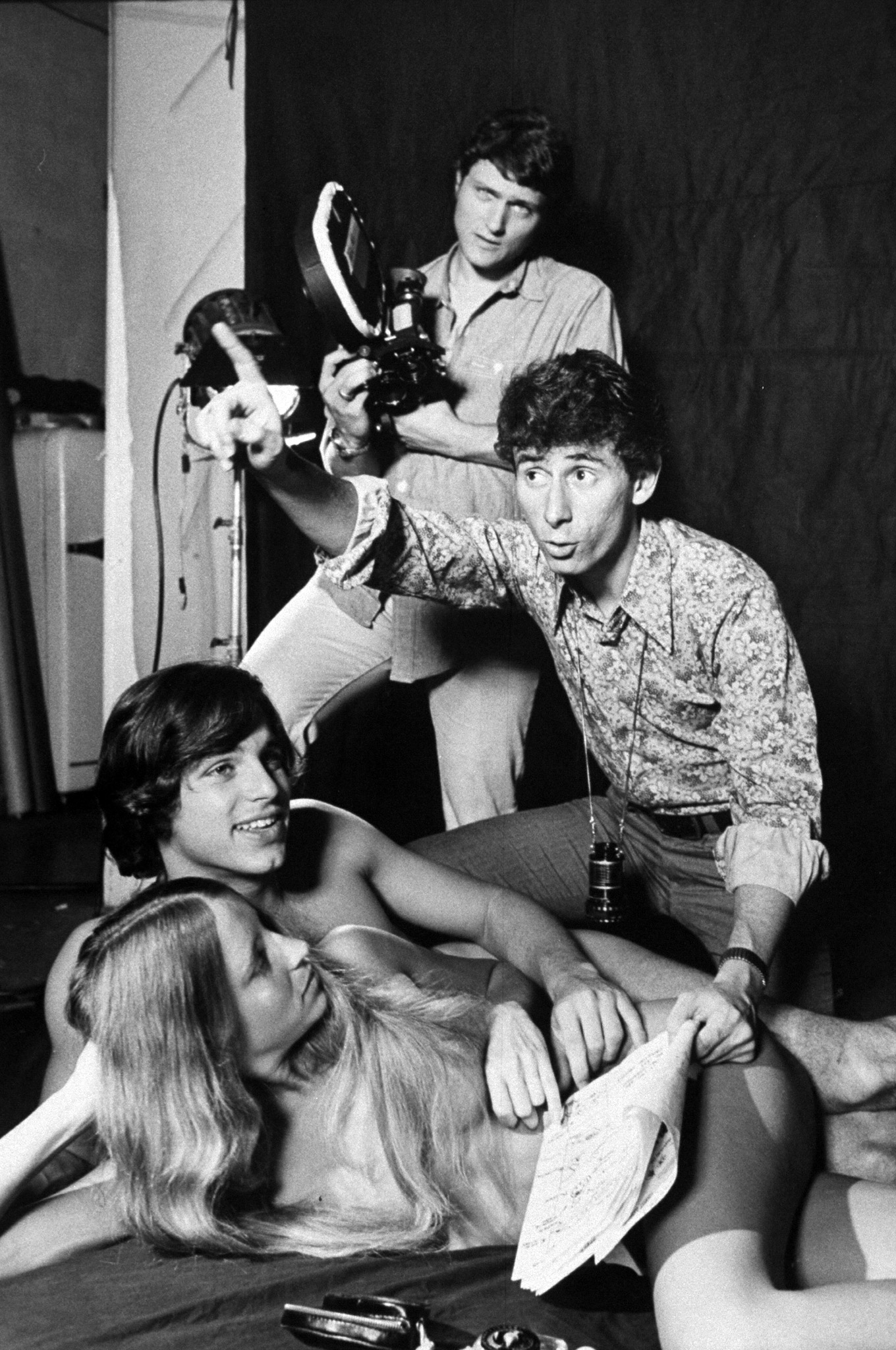

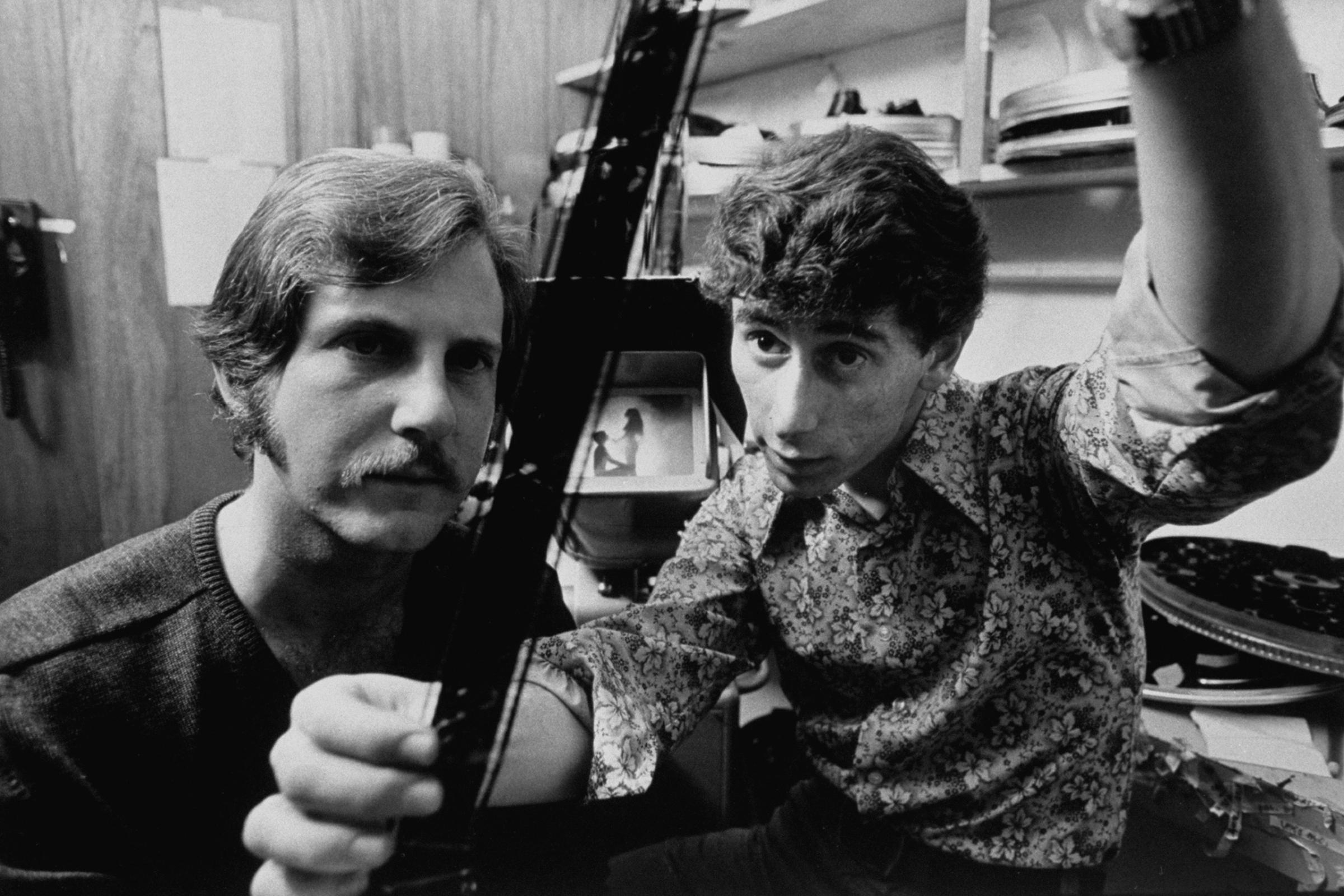

A pornographic filmmaker, during an interview for a 1970 LIFE cover story about his industry, offered a bold prediction: “When everything is shown that can be shown,” he prophesied, “boredom will set in.” The ensuing decades, of course, have proven him incontrovertibly wrong: Pornography in the U.S. has grown from a $1 billion annual industry to a $10-to-$12 billion industry, and the Internet has made both the creation of and access to pornographic materials easier than ever before.

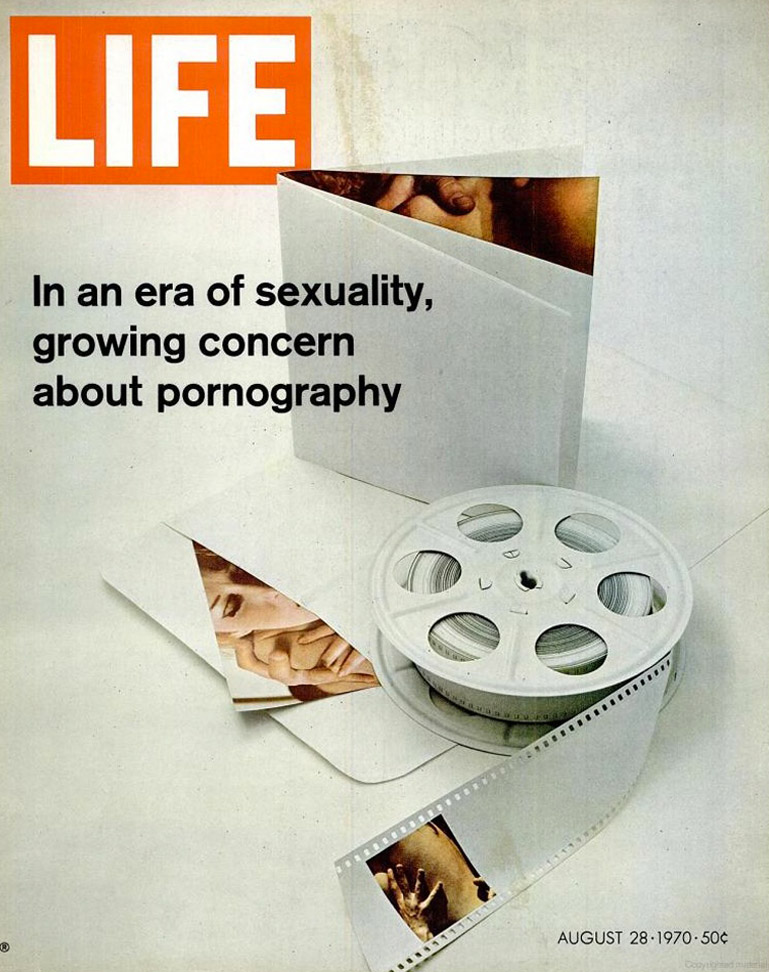

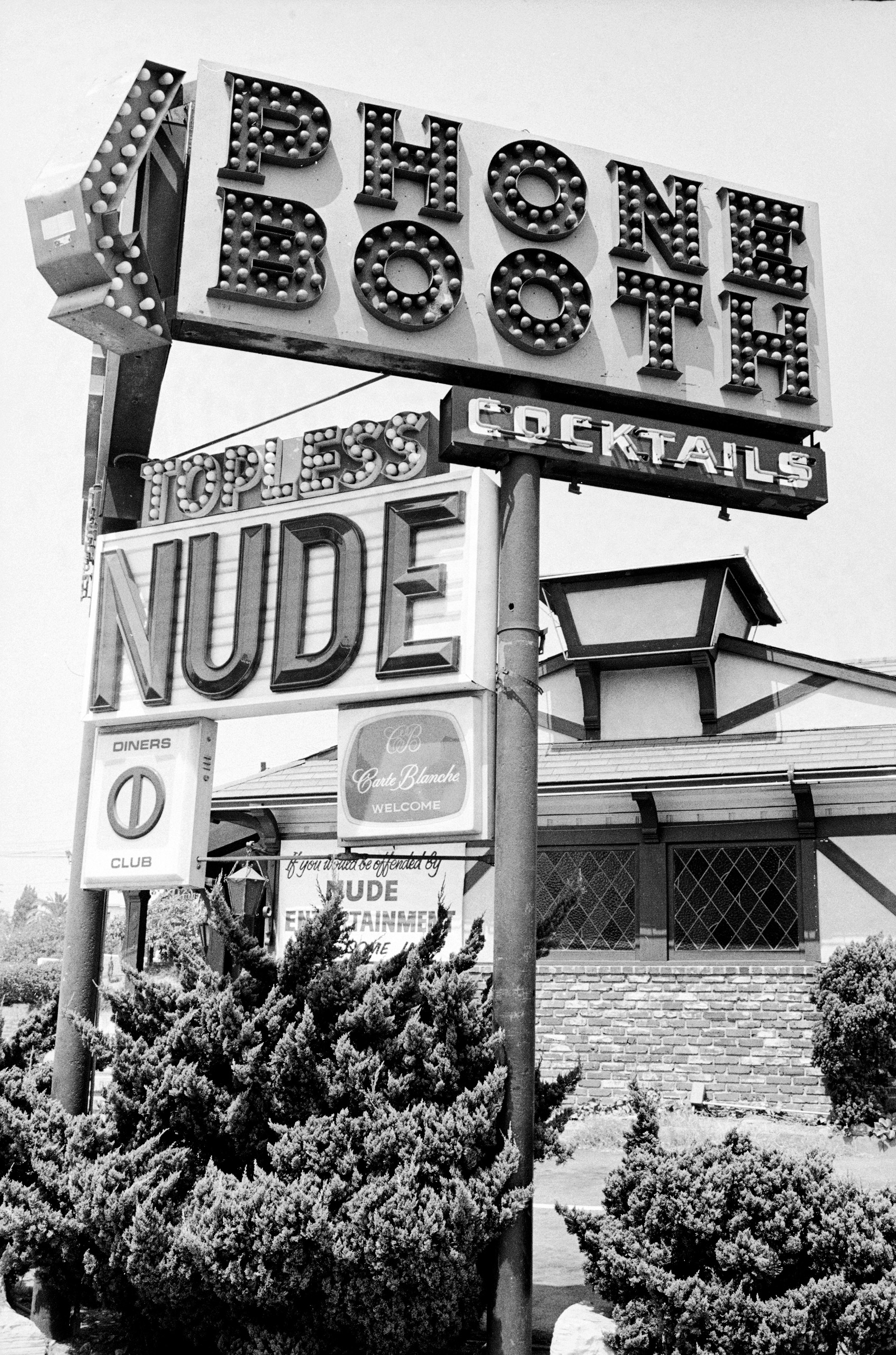

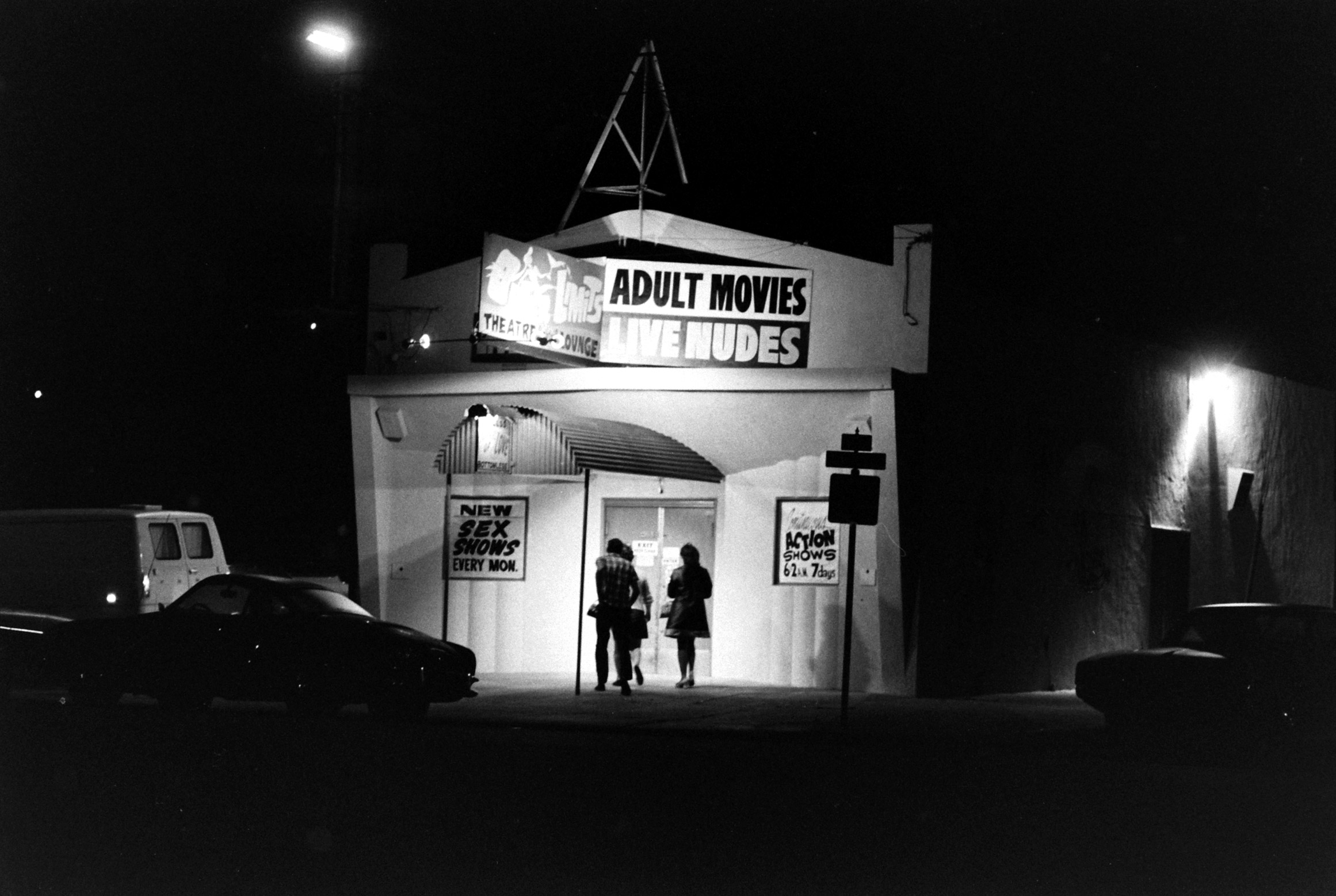

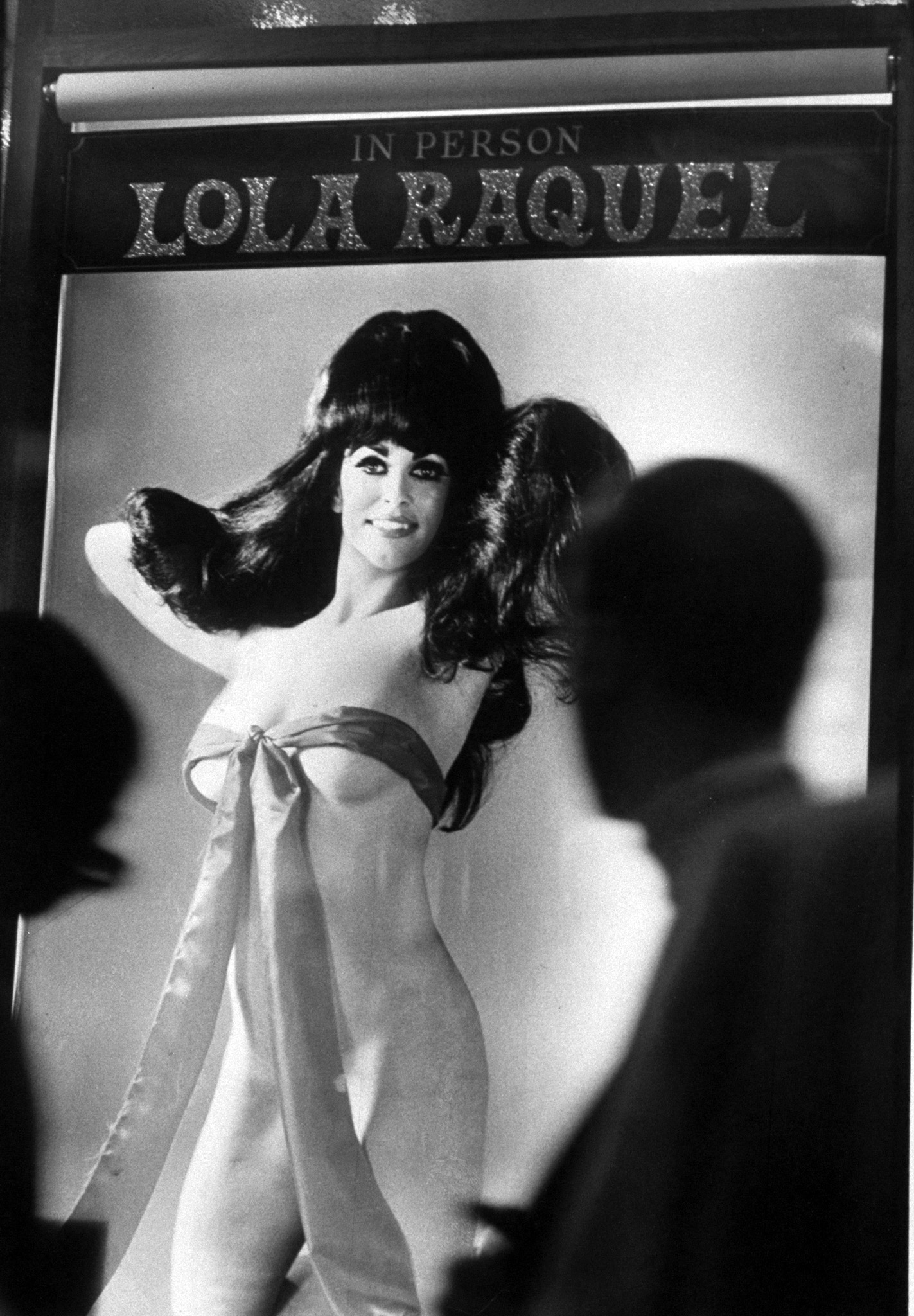

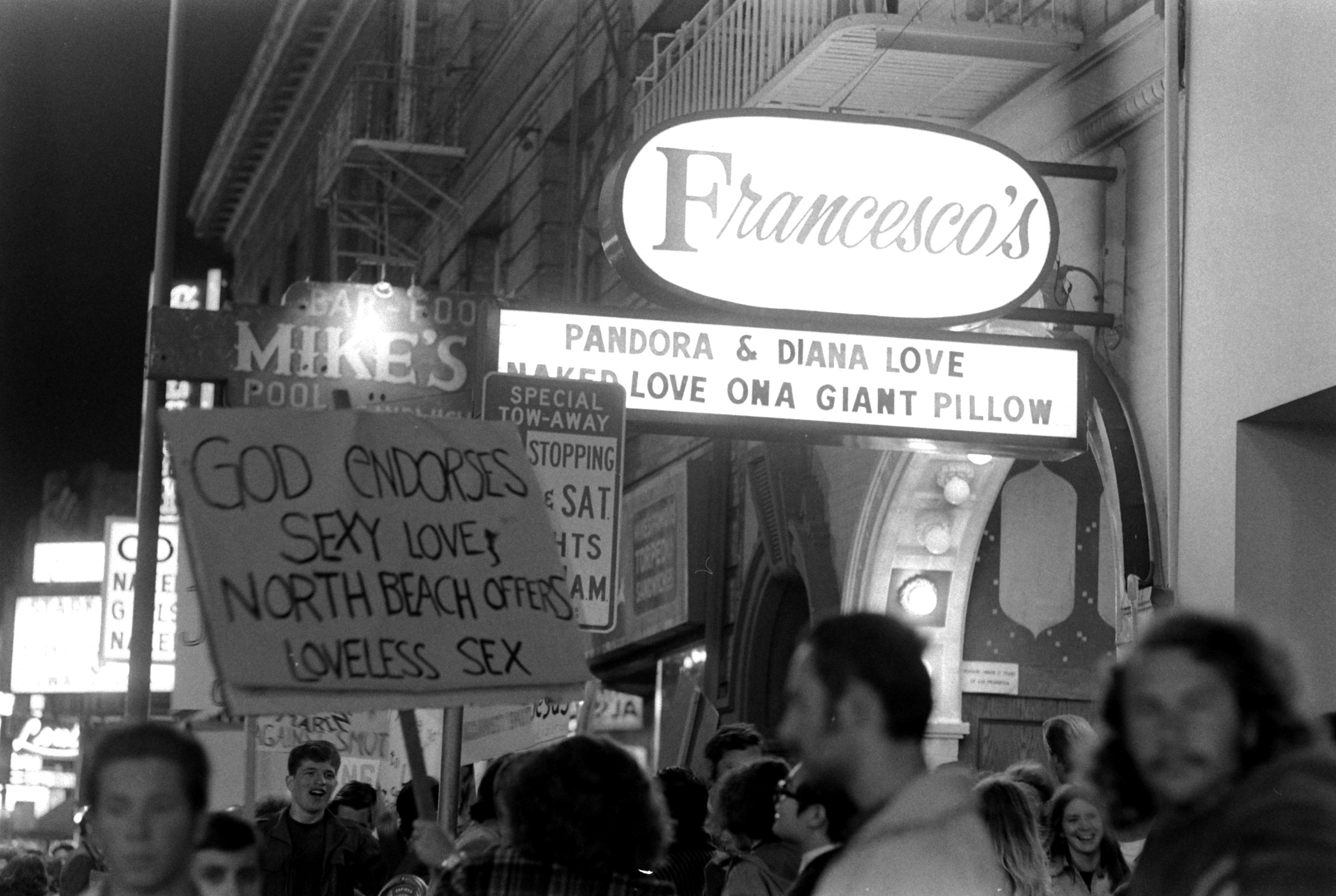

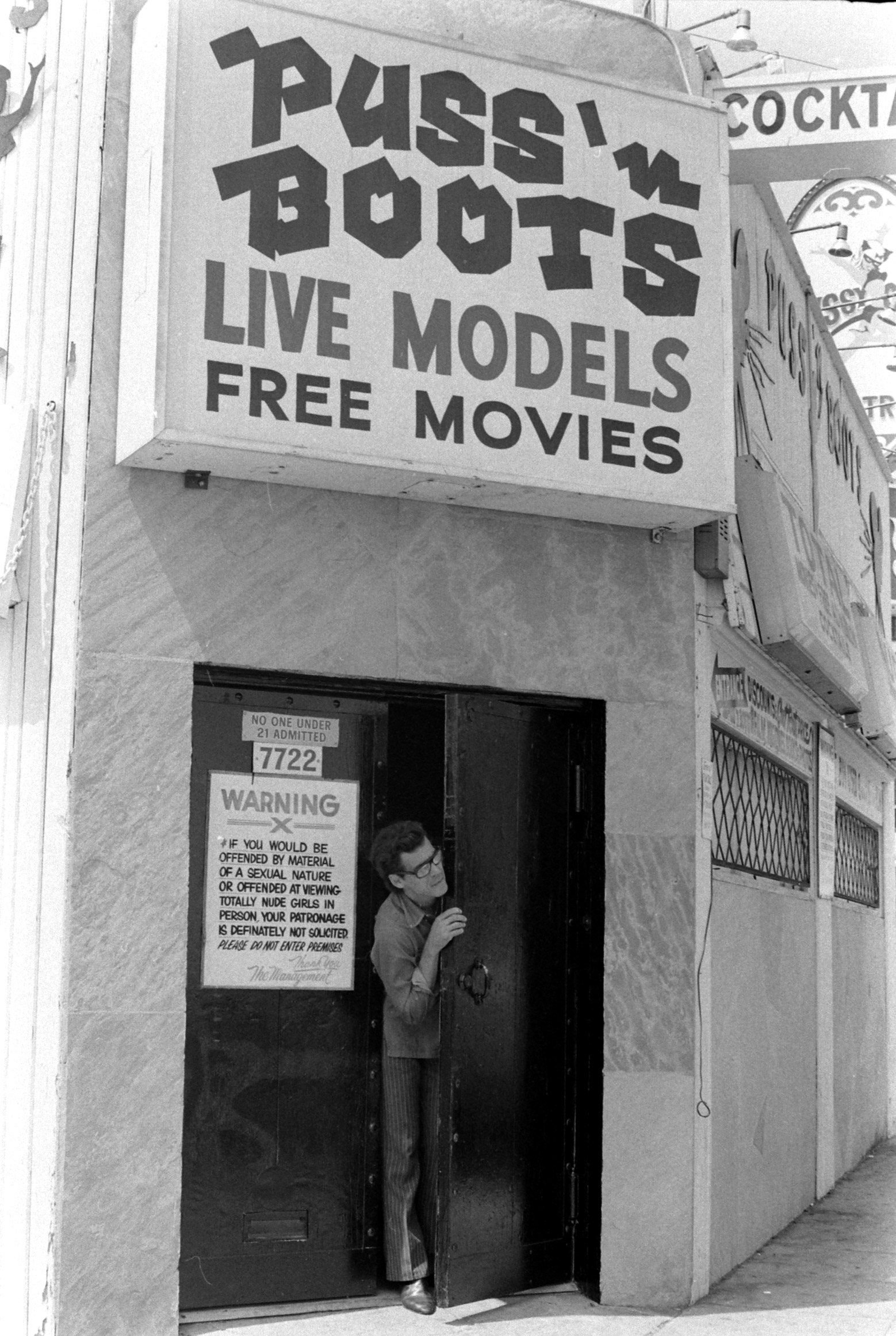

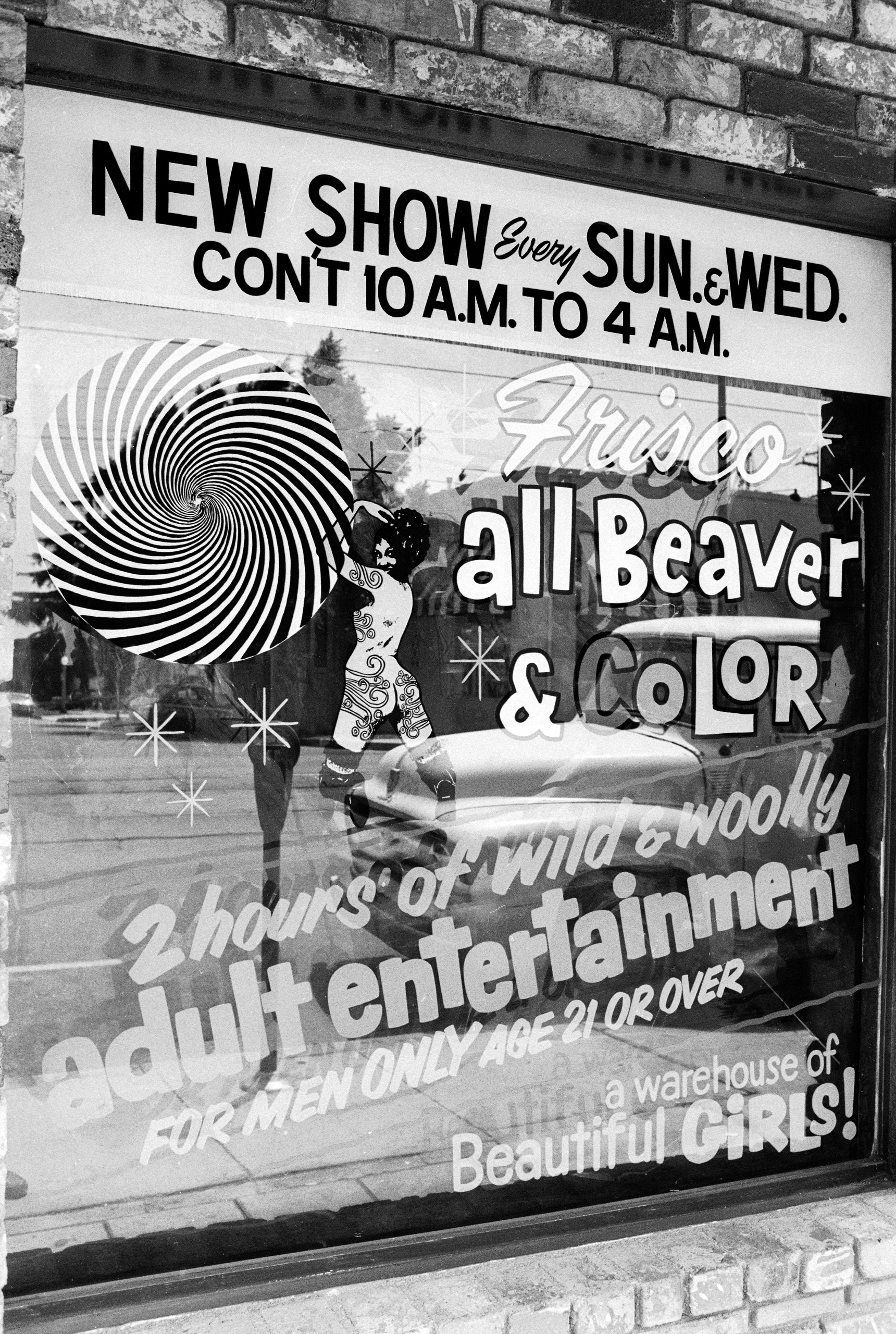

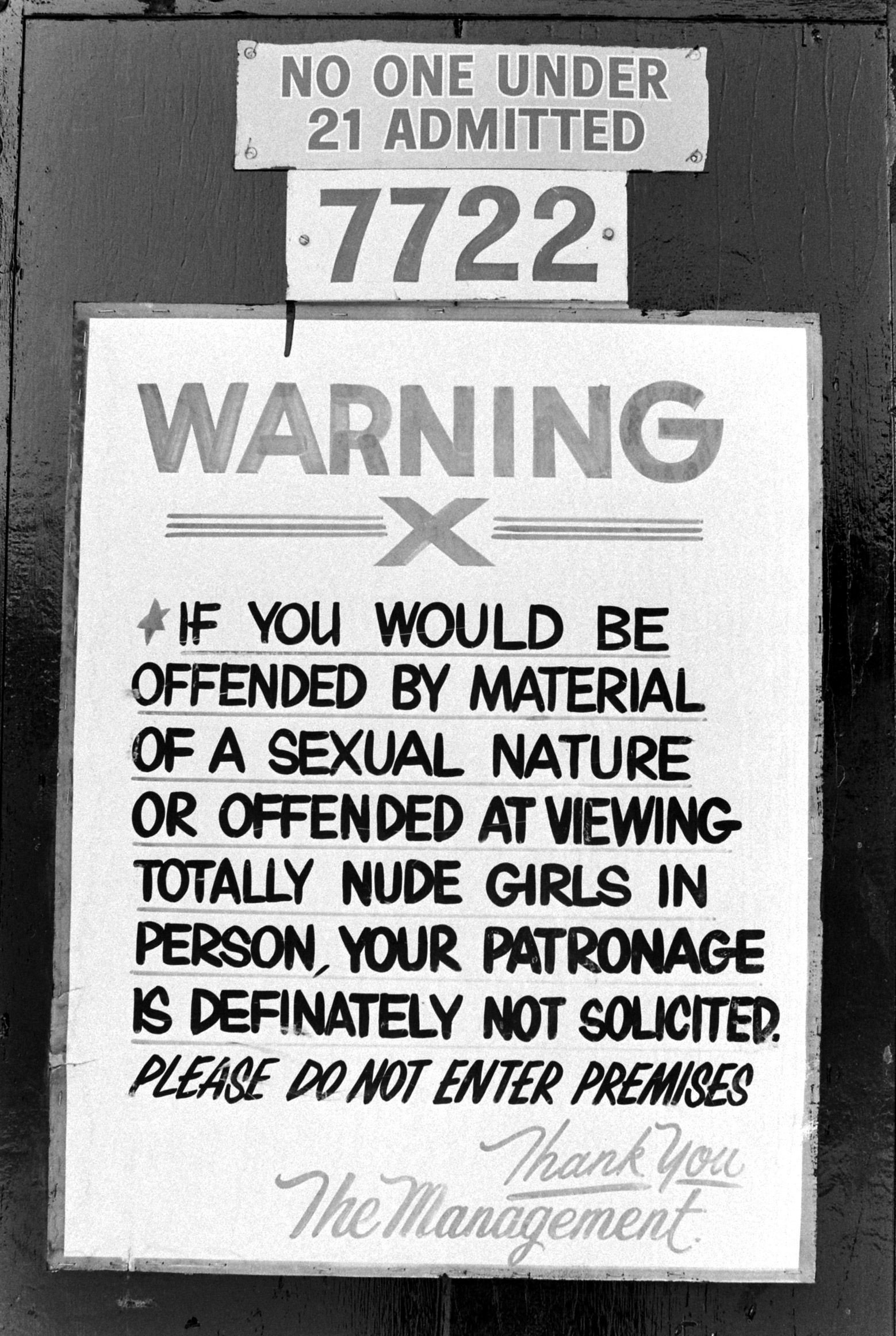

But in 1970, as the sexual revolution challenged traditional perspectives on love and sex, the industry was stuck between increasing demand and growing concerns over morality. The “torrent of sexuality,” as LIFE called it, was a subject of debate from the Capitol Building to small-town living rooms, as elected officials and private citizens debated not only what to do about porn, but also how to define it in the first place.

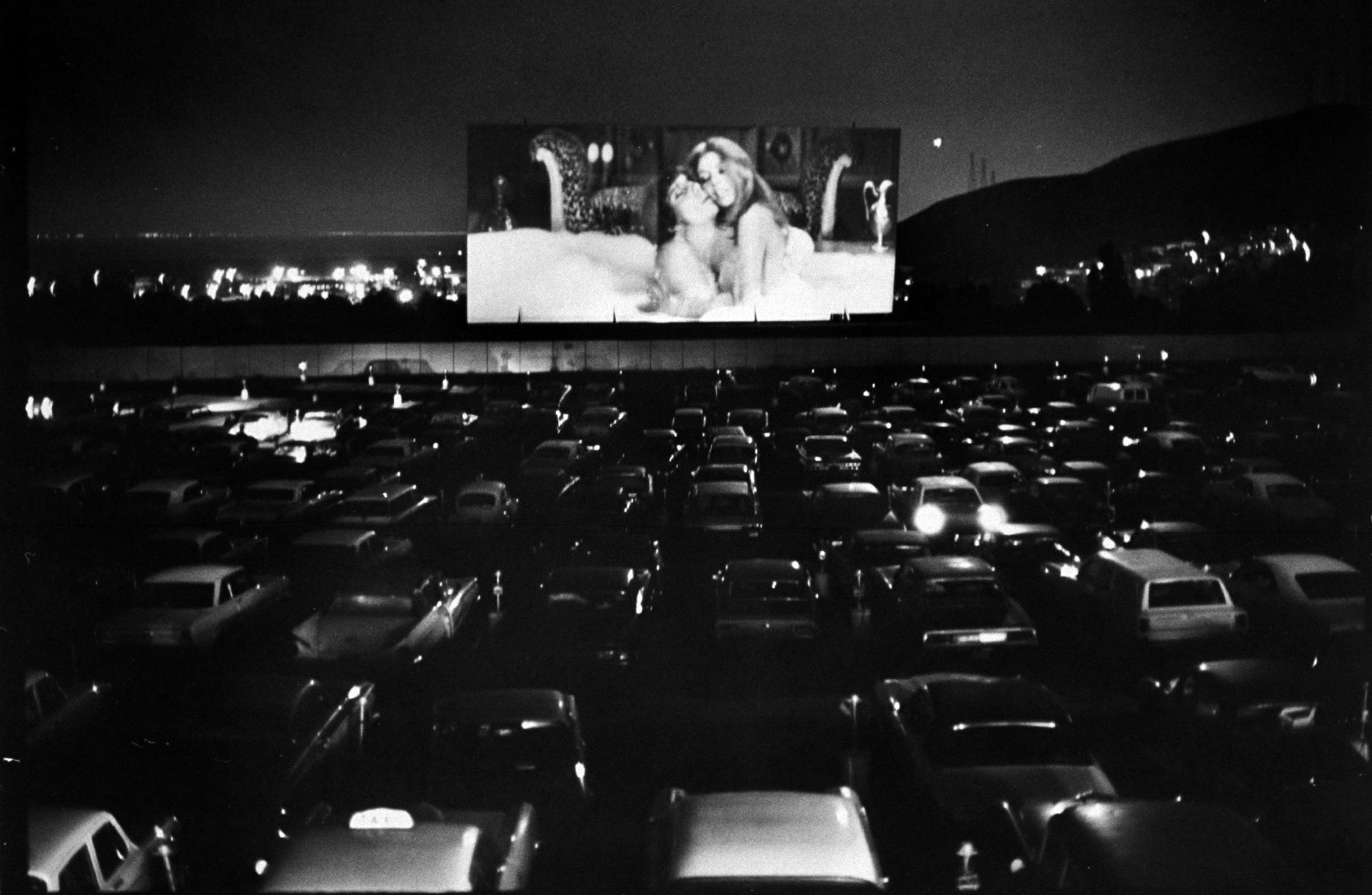

From a business perspective, there was never any question as to pornography’s value. Overhead was low and profit potentials were soaring: One racy film with a loose premise about industrial espionage cost $125,000 to make and was expected to gross more than $10 million. (That’s about $61.5 million in today’s dollars.) An Iowa theater owner earned $1,600 in one week showing the Julie Andrews musical film Darling Lili. He made nearly twice that amount in a single night showing the less innocent Love Camp No. 9.

As the business thrived, President Nixon became more determined to stifle it. Following the Supreme Court decision in Stanley v. Georgia, which established that people could view whatever they wished in the privacy of their own homes, Nixon established the President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. Despite the Commission’s finding that there was no evidence to suggest that pornography was harmful, Nixon urged the formation of a “citizens’ campaign against obscenity.”

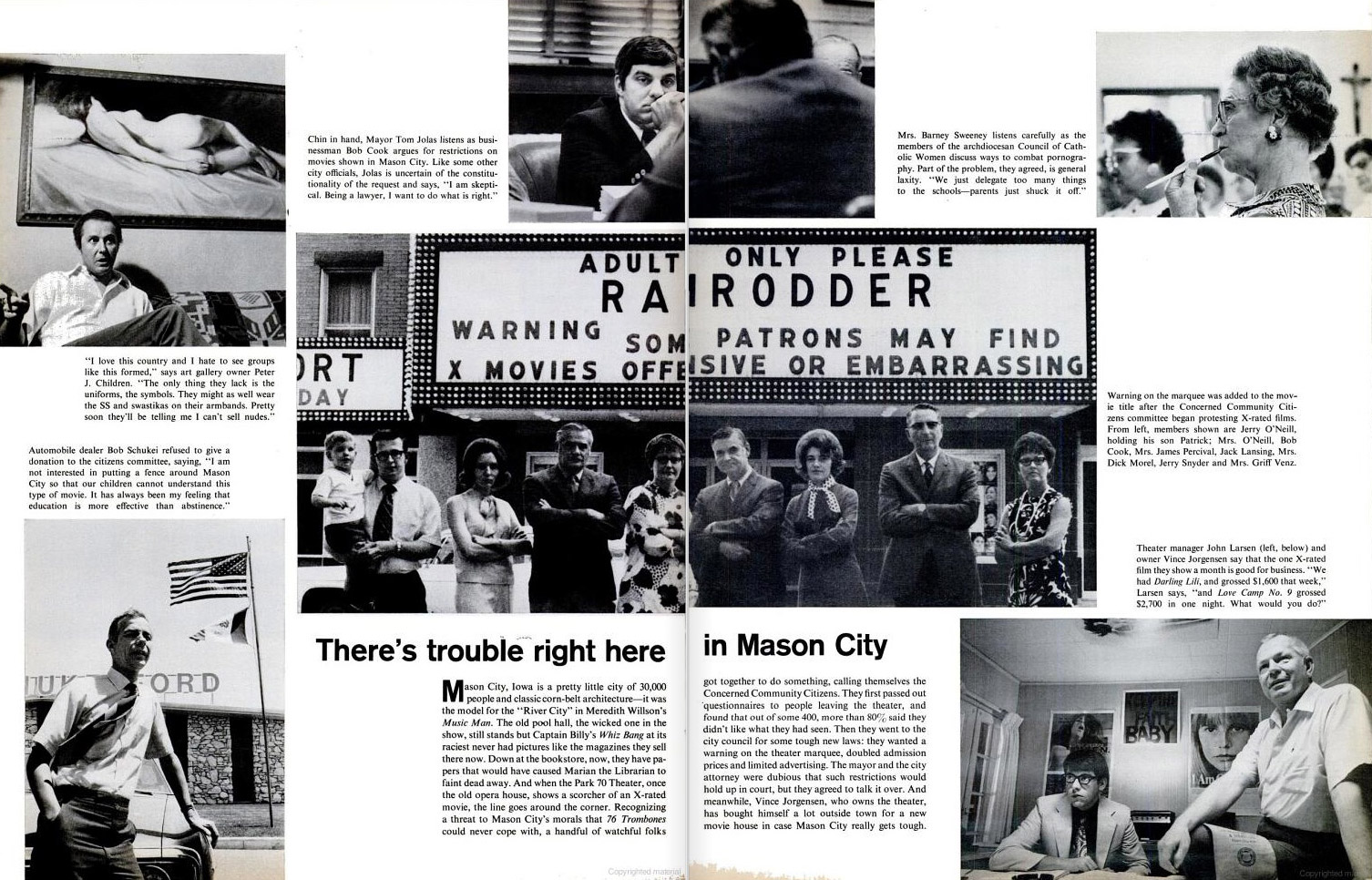

And campaign the citizens did. In the small Iowa town of Mason City—the same town where Love Camp No. 9 drew such an eager audience—the Concerned Community Citizens group was protesting what they viewed as an infiltration. They advocated for higher ticket prices, warnings on the marquee and less prominent placement of pornographic books in bookstores.

But their efforts were not without opposition, not only from businessmen like the theater owner, but also from fellow citizens who believed in free speech and education over censorship. The divide, like many of the era, was largely generational. Mason City’s young adults were more concerned about the environmental impact of the cement dust from nearby factories than fictional movies which, they said, were having no impact on their own behavior.

One parent, a local car dealer, occupied a position somewhere between freedom and defeat. To a fellow parent, he suggested, “You cannot shield your children from life. And I don’t care how you try.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com