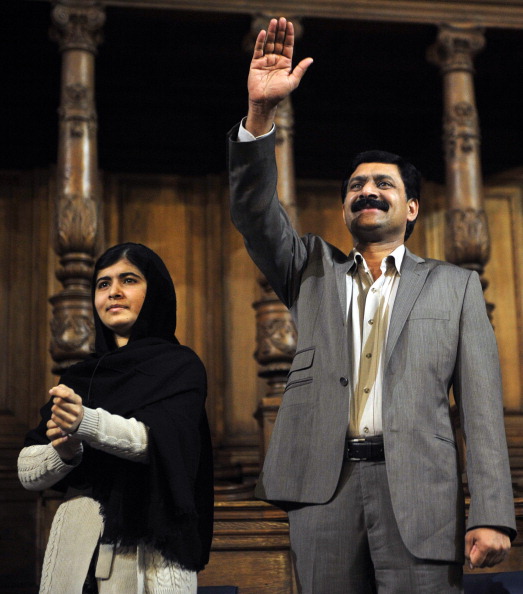

Before 17-year-old Malala Yousafzai received the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, she ran her acceptance speech by one guy: her father Ziauddin. After all, it was Zia’s support for the rights of girls in Pakistan’s Swat Valley that inspired his daughter to write about life under the Taliban for the BBC. Zia encouraged Malala as she rose to international prominence through her own advocacy and, when the Taliban retaliated by shooting his daughter in the head, he left behind the school system he oversaw to be by her side in England throughout her remarkable recovery. So, what do you say to your daughter right before she becomes the youngest Nobel laureate ever?

“I kissed her on the head and wished her the best of luck,” he says with a chuckle. “That’s it.”

In your TED talk, you discuss your desire to contradict the powerful forces that define “honor” for boys and “obedience” for girls in your culture. Where does this desire come from and why don’t more fathers in the Swat Valley have it?

Generally, these two values of honor and obedience, outwardly they look positive. But in the context of a patriarchal society there are issues. Boys inherit from their forefathers that their sisters are like their honor. Whenever anything happens, they are incited and they bully their sisters, they even kill, if they find their sisters having an illicit relationship with boy, or anything that is not acceptable for their society.

The other value, which we call obedience and which is taught to girls — they should always submit to whatever is done to them and they have no right to say anything. If they are married very early or if they are married to anybody they don’t like, whatever rights are violated at home by their brothers, they are supposed to be submissive.

Why did I have this desire in me to change this? When I saw the suffering of the people, of women especially — and even the boys suffered — because I saw many couples who were killed in the name of “honor killings.” They suffered because this value of obedience or this value of honor, it was misused. There was naturally a desire in my heart to change this situation.

You ask why many fathers aren’t like me, the reason is that many people in society — whatever society they’re in — they like to live in-line with existing values and norms. It’s very easy to live as all other people live and to believe we are the victims of whatever happens in a bad society. It’s very difficult to challenge those norms and values which go against basic human rights.

You were very aware that your beliefs regarding women made you a target for groups like the Taliban. How did you weigh that risk against your need to encourage Malala to speak her mind and live her life as she saw fit?

I always challenged the Taliban and challenged the terrorists when I was working as an educator and as a human rights activist in Swat. [At one] very big gathering of parents and students, nearby the stage there was a man with a small girl child in his lap. During the speech, I just took her in my lap and I asked the people would you like to die, or to keep your daughters ignorant? And the gathering raised their hands and said no, we will die for the right of our daughters’ education. It was so inspiring, so motivating.

I encouraged [Malala] to speak, but I never thought it would come with such a big risk. I never thought that the Taliban would come to kill a child, especially a woman. Because I know that most of them, they are from Swat, and they are Pashtun, and it is culturally unacceptable that you attack a woman, and you attack a child, so Malala had two cultural protections. I can say that I misread or miscalculated the ethics of the Taliban, and what happened, that was horrible.

What about with your wife? How did the two of you assess opportunities like her invitation to blog for the BBC, when doing so came with so much inherent risk?

To be honest, we never thought that it was an opportunity. I think we took it as a call of duty. Because, being concerned residents of Pakistan and Swat, we thought that it’s our duty that when our basic rights are being violated and heinous atrocities and heinous crimes are inflicted against the people of Swat and they are victims of inhuman atrocities and barbarism, we thought that it is our human responsibility to speak against all of what was happening with our people. And my wife, to be honest, she is a very courageous, a very brave woman, and she always stood for truth. As the Holy Quran says, righteousness, the truth, it will come, and falsehood will go, because falsehood has to go.

Now that your daughter is as engaged in the issue of equality and empowerment for women as you are, what have you learned by watching her work?

I think that now she is more engaged than me, to be honest. Before, I was a leader of my small community in Swat. I campaigned for education, I campaigned for women’s rights, I campaigned for children’s rights, and because of living in the same environment and having an inborn passion for human rights, Malala joined me as a companion in that campaign. But when Malala was shot, she was reborn. Now, she’s leading and I’m one of her supporters. There are millions of supporters and I’m one of them. I have found her more successful than me, wiser than me, and more resilient than me. I have learned from her many things. I think for a father, maybe, a father always teaches. He’s supposed to teach. But, I learn from my many students and particularly from her, I learned how to be fair and honest to one’s own self, and how to be fair and honest to others. And I learned from her how to be clear in vision, and in one’s objectives. So also I have learned from her how to be beyond the greed of fame and name, and how to be sincere and simple.

You’re a pretty brave guy in your own right, but what have you learned about courage from Malala?

I think we might best look at her journey before the attack on her life and after the attack on her life. I really have found her braver than myself, to be honest, because I remember that when we used to go to different seminars and different conferences and we used to speak for the right of education, I used to compromise. I used to tell her “Oh, look Malala, don’t name the Taliban, they’re terrorists, don’t name them because they’re dangerous people.” And when she stood at the podium she named them always, in spite of my advice not to name them. And after the worst kind of trauma that God should protect every person, every child, from … she had the resilience and the courage to stand again and talk with more courage, more commitment, more resilience, for the right of children, for the right of women, and for the right of education. So I think that it’s really inspiring and I can simply say that she’s braver than me.

What advice do you have for a father whose children are in a situation similar to Malala’s?

I would advise the leaders of all those communities who are in conflict, all those countries that are in conflict, or suffering from terrorism: Don’t be hypocrites and don’t be apologetic about terrorism, and don’t be cowards when it comes to your children’s rights. Be brave, and stand for your children. It’s your duty, not your children’s duty. Don’t fail them. It is the society’s elders’ duty, to protect their children, and to make the right decisions that their children should be safe. I don’t wish any father to be in the situation in which I was.

What’s it like to watch your daughter accept the Nobel Peace Price?

It was a moment of honor. I was thinking that this girl, she is getting the Nobel Peace Prize, and she belongs to a nation that is notorious for terrorism, and now this 17-year-old girl, she is raising the flag of peace. Peace and education. In her own region, 400 public schools have been bombed, and she is raising the torch of public education and the flag of peace, and she is there to lead the world. It was a moment of real happiness for me, I think for a father, what could be more than that?

This article originally appeared on Fatherly

More from Fatherly:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com