The credit score is a strange piece of financial alchemy. And yet many Americans see their scores—which claim to encapsulate everything from one’s credit history to one’s attitude toward debt—as normal, even natural.

But, of course, it is not. Credit reporting, in its modern sense, is fewer than 200 years old—invented as part of America’s transition to capitalist modernity. Already, however, its history has proved both alarming and empowering, helping millions realize the American Dream through access to credit, while integrating many more into surveillance networks rivaling the NSA’s. Just as importantly, it has saddled the majority of Americans with a lifelong ‘financial identity’: an un-erasable mark that reflects bad behavior in the past and compels good behavior in the future.

At a moment when credit reports are being used to inform a wide range of life decisions—from where people live and work, to how much they’ll pay for insurance and utilities—this history is more important than ever.

***

For much of debt’s 5,000-year history, credit reporting has been a deeply personal practice. In 18th-century America, for instance, country storekeepers secured loans by asking well-regarded neighbors to vouch for their character to bankers and merchants. And urban creditors mined far-flung rural acquaintances for rumors and hearsay regarding applicants for credit.

Beginning in the 1820s, however, credit reporting began to modernize, as the density of business transactions made the old system too cumbersome. New bankruptcy laws also made loans a riskier proposition. The result was a series of experiments in standardizing credit evaluation. Though these experiments were limited to commercial credit—loans to businesspeople—they would have important implications for the later history of consumer credit rating.

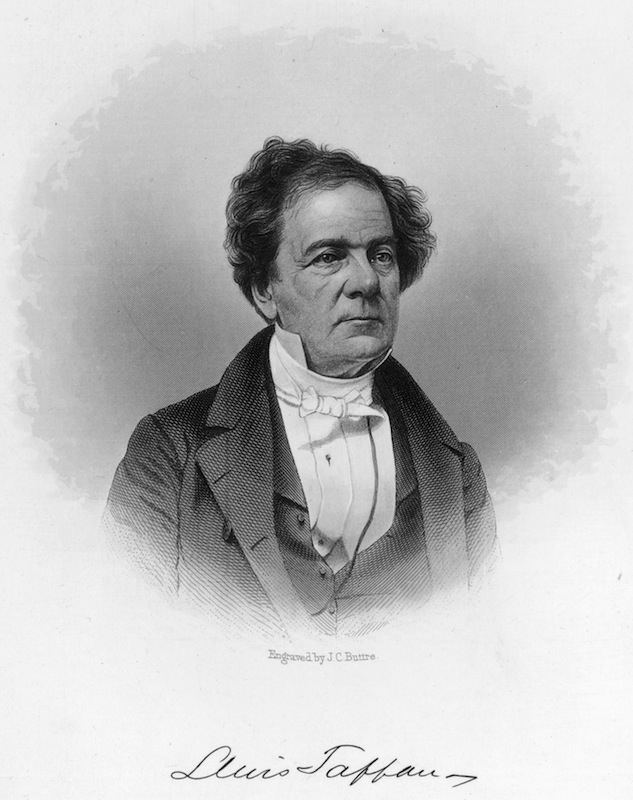

The most important of these experiments was the Mercantile Agency, founded in 1841 by merchant Lewis Tappan. Burned in the panic of 1837—a depression caused by merchants’ over-extension of credit—Tappan set out to systematize the rumors regarding debtors’ character and assets. Soliciting information from correspondents throughout the country, Tappan’s agency distilled these reports in massive ledgers in New York City.

These early reports were incredibly subjective. As such, they were colored by the opinions of their predominantly white, male reporters, as well as their racial, class and gender biases. One credit reporter from Buffalo, N.Y., for instance, noted that “prudence in large transactions with all Jews should be used.” And a reporter in post-Civil War Georgia described A. G. Marks’ liquor store as “a low Negro shop.”

The subjectivity of these reports had two important consequences. First, it reinforced existing social hierarchies, serving as an early form of redlining. Second, the jumble of rumors contained in early reports proved difficult to translate into actionable lessons. What was one to make, for instance, of reports like the following on Philadelphia merchant Charles Dull from Tappan’s Mercantile Agency: “there is a g[oo]d prej[udi]ce as among the trade—enjoys generally a poor reputation as a man, but is gen[erall]y sup[pose]d to have money”? Increasingly, then, subscribers to the Mercantile Agency and its rival, the Bradstreet Company, began to demand a simplified method of evaluation.

The result was a new thing under the sun: a pseudo-scientific sleight of hand that converted the (mis)information in borrowers’ reports into actionable financial ‘facts.’ Pioneered by Bradstreet in 1857, commercial credit rating would assume a more lasting form in 1864 when the Mercantile Agency, renamed R. G. Dun and Company on the eve of the Civil War, finalized an alphanumeric system that would remain in use until the twentieth century. (The companies later merged, becoming Dun & Bradstreet.)

Though intimately related to contemporary developments in population management, including espionage and statistical analysis, credit scoring was nevertheless novel in its own right. Its arrival meant that commercial borrowers now possessed what scholar Josh Lauer has called a ‘financial identity’: an identifier that not only purported to summarize one’s financial history, but which threatened to plummet, should one suffer a lapse in fortune or discipline. Reflecting on this development, one 19th-century commentator quipped that “the mercantile agency might well be termed a bureau for the promotion of honesty.”

Thus, by the end of the Civil War, the three pillars of modern credit reporting were in place: private-sector mass surveillance that made credit reports possible, bureaucratic information-sharing that made them widely available and a rating system that made them actionable.

It would take nearly a half-century, however, before all three of these pillars would be transferred from commercial to consumer credit evaluation.

***

Consumer credit reporting, like consumer debt, was unnecessary in early America. Production and consumption were so thoroughly blended that a loan to a farmer for agricultural supplies would inevitably help him or her purchase clothing and furniture as well.

By the second half of the 19th century, however, many Americans conceived of production and consumption as distinct realms. Just as importantly, the success of the labor movement meant that many were working less and making more. Eager for these workers’ hard-earned dollars, many retailers—including America’s newfangled department stores and auto industry—extended generous credit lines. Though prone to abuses (auto and consumer-goods financing were deeply implicated in the Great Depression) these credit lines nevertheless helped put the trappings of middle-class life in the hands of many Americans.

The men and women in charge of evaluating consumer credit were not organized into a single dominant firm, as they were in commercial credit rating. More often, they were employed as credit managers for retailers. But that did not stop them from adopting techniques pioneered by firms like Dun & Bradstreet. Forming a national association in 1912, these credit managers used their professional organization to perfect practices for collecting, sharing and codifying information on retail debtors.

This is not to suggest, however, that there were no important pioneers in the consumer credit-reporting sector. While many early agencies were short-lived, firms like Atlanta’s Retail Credit Company left an enduring impact. Founded in 1899, RCC developed files on millions of Americans over the next 60 years. This information included not just data on credit, capital and character, but information on individuals’ social, political and sexual lives as well. Already a magnet for criticism, the outcry against RCC reached a fever pitch in the 1960s when the firm revealed plans to computerize its records.

The backlash was swift and heated. “Almost inevitably,” argued privacy advocate Alan Westin in a 1968 New York Times article, “transferring information from a manual file onto a computer triggers a threat to civil liberties, to privacy, to a man’s very humanity because access is so simple.” Say goodbye to second chances, Westin claimed: digitized files would make it impossible to outrun one’s past.

Knowingly or otherwise, Westin was echoing critiques that had haunted credit reporting since its earliest days. Writing in Hunt’s Merchant Magazine in 1853, a contributor lamented that, “[g]o where you may to purchase goods, a character has preceded you, either for your benefit or your destruction.” And in 1936, TIME exposed credit bureaus’ astonishing surveillance powers. Chronicling an unfortunate woman’s flight from Chicago to Los Angeles, the story showed how quickly reporters discovered her debts and dark past.

But while Westin’s comments may have drawn on a deeper history, their impact was novel. Indeed, the outcry against the computerization of credit-reporting data resulted not only in congressional investigations, but also in the passage of the Fair Credit Reporting Act in 1970—a landmark piece of legislation that required bureaus to open their files to the public; expunge data on race, sexuality and disability; and delete negative information after a specified period of time.

However, far from halting credit reporting, FCRA helped usher in its golden age. RCC, for instance, came away from congressional hearings with a black eye, but did not disappear. Instead, it changed its name to Equifax in 1975 and continued on its course of computerization. In time, it was joined by Experian and TransUnion. Together, they constitute the ‘Big Three’ of consumer credit reporting.

Despite expanding demand for their services, however, all three firms continued to be hamstrung by problems that had long afflicted the industry: namely, the difficulty of interpreting and comparing their reports. To resolve this, they began working with a tech company to develop a credit-scoring algorithm. The company’s name was Fair, Isaac and Company—though it is known today as FICO.

Fair, Isaac and Company was well positioned to take on this task. Founded in 1956, the firm had already been selling credit-scoring algorithms for decades when the Big Three began their quest for an industry-standard credit score. The result, which hit the market in 1989, was remarkably similar to the algorithm still in use today.

Quickly implemented throughout the consumer credit industry, the FICO score represented the final consummation of a process that began with the Bradstreet Company’s first credit-rating manual. Its arrival meant that, thenceforth, nearly everyone in America would have a codified financial identity. No longer the sole province of commercial borrowers, financial identity had become a fact of life in modern America.

***

History reminds us that, common as it now seems, credit scoring is anything but universal. People in the past rightly worried about the concentration of power in the hands of secretive, privately-held organizations—firms that Lewis Tappan regularly had to defend against charges of espionage, and that at least one outraged antebellum commentator described as a new Inquisition. Even today, worries remain. As in the past, credit reporting can function as a way of maintaining social hierarchies. Especially among poorer Americans, low credit scores often translate into larger down payments and higher interest rates on purchases—terms that place an undue strain on household budgets and that often result in high rates of bankruptcy and default, which in turn lower credit scores even more.

Not all of history’s lessons, however, are so unflattering. Credit reporting was essential to opening financial opportunities to a broader cross-section of Americans—allowing them to buy not just baubles, but life-changing goods as well.

The alternative to credit reporting, moreover, is a dismal one. Before the modern era, credit was anchored in personal relationships. These relationships could be nurturing. But often they were predatory. Now, obviously, financial ne’er-do-wells have not disappeared. But FICO scores do at least allow individuals to move easily between lenders.

Most of all, knowing the history of credit reporting shows us why it’s important to pay attention to the institution as a whole, and not just to our own scores. Today, credit reports are used to inform decisions about housing, employment, insurance and the cost of utilities. But errors on credit reports are common. And many of the consumer protections in FCRA are being circumvented by opaque, in-house rating systems under development at major financial institutions.

Though cloaked in algorithmic objectivity, the raison d’être of the modern credit score is the same as the scrawled reports in Tappan’s massive ledgers: to determine not just who can repay their debts, but who will choose to do so. To answer this essentially moral question—and to compel ‘good’ behavior—credit bureaus have developed surveillance and information-sharing techniques rivaling anything in the arsenal of the state. These have brought benefits, true. But they have also inscribed Americans’ financial histories in the indelible digital ledgers of modern capitalism—for the mighty to see, and the majority to glimpse.

In the face of power like this, what choice do we have but vigilance?

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sean Trainor has a Ph.D. in History & Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from Penn State University. He blogs at seantrainor.org.

1929: The Crash of ’29

Nobody knew, as the stock market imploded in October 1929, that years of depression lay ahead and that the market would stay seized up for years. In its regular summation of the president’s week after Black Tuesday (Oct. 29), TIME put the market crash in the No. 2 position, after devastating storms in the Great Lakes region. TIME described the stock-swoon this way: “For so many months, so many people had saved money and borrowed money and borrowed on their borrowings to possess themselves of the little pieces of paper by virtue of which they became partners of U.S. Industry. Now they were trying to get rid of them even more frantically than they had tried to get them. Stocks bought without reference to their earnings were being sold without reference to their dividends.” The crisis that began that autumn and led into the Great Depression would not fully resolve for a decade.

Read the Nov. 4, 1929, issue, here in the TIME Vault: Bankers v. Panic

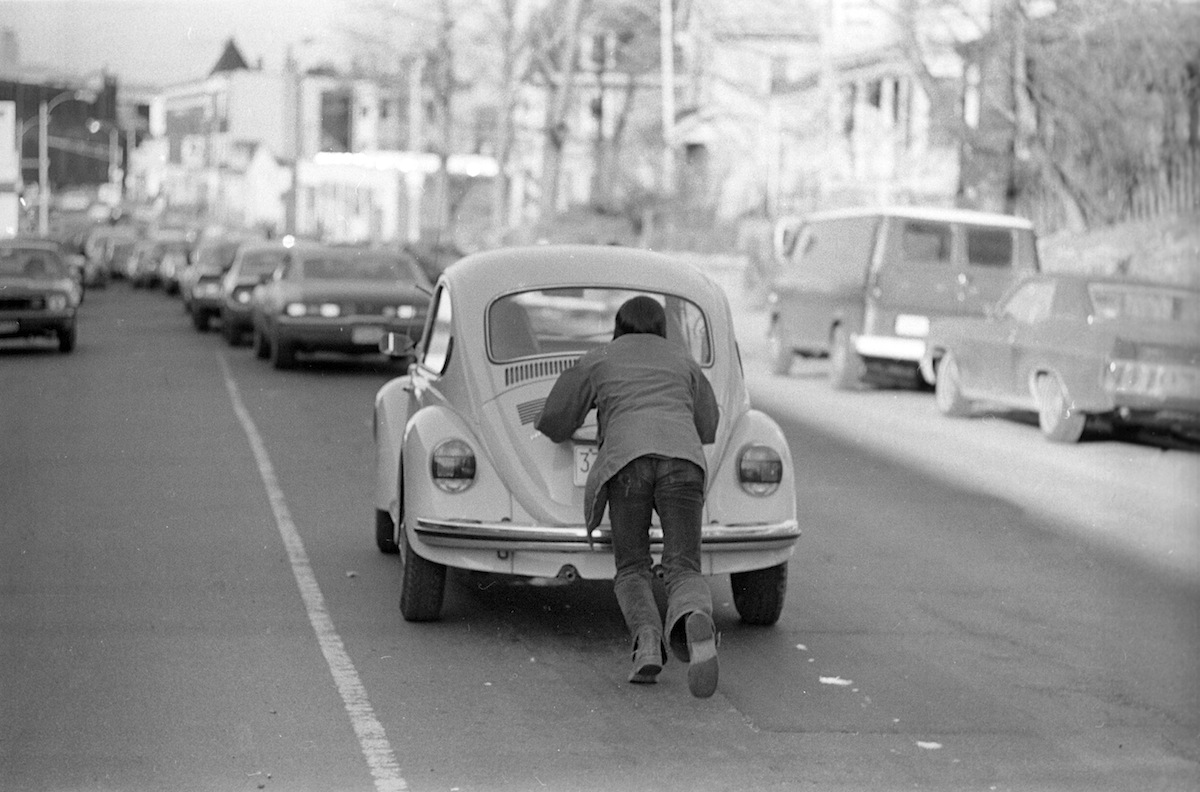

1973: The OPEC Embargo

Here’s proof that the every-seven-years formulation hasn’t always held true: The OPEC oil embargo is widely viewed as the first major, discrete event after the Crash of ’29 to have deep, wide-ranging economic effects that lasted for years. OPEC, responding to the United States’ involvement in the Yom Kippur War, froze oil production and hiked prices several times beginning on October 16. Oil prices eventually quadrupled, meaning that gas prices soared. The embargo, TIME warned in the days after it started, “could easily lead to cold homes, hospitals and schools, shuttered factories, slower travel, brownouts, consumer rationing, aggravated inflation and even worsened air pollution in the U.S., Europe and Japan.”

Read the 1973 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: The Oil Squeeze

1981: The Early-’80s Recession

The recession of the early 1980s lasted from July 1981 to November of the following year, and was marked by high interest rates, high unemployment and rising prices. Unlike market-crash-caused crises, it’s impossible to pin this one to a particular date. TIME’s cover story of Feb. 8, 1982, is as good a place as any to take a sounding. Titled simply “Unemployment on the Rise,” the article examined the dire landscape and groped for solutions that would only come with an upturn in the business cycle at the end of the year. “For the first time in years, polls show that more Americans are worried about unemployment than inflation,” TIME reported. A White House source told TIME: “If unemployment breaks 10%, we’re in big trouble.” Unemployment peaked the following November at 10.8%.

Read the 1982 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: Unemployment: The Biggest Worry

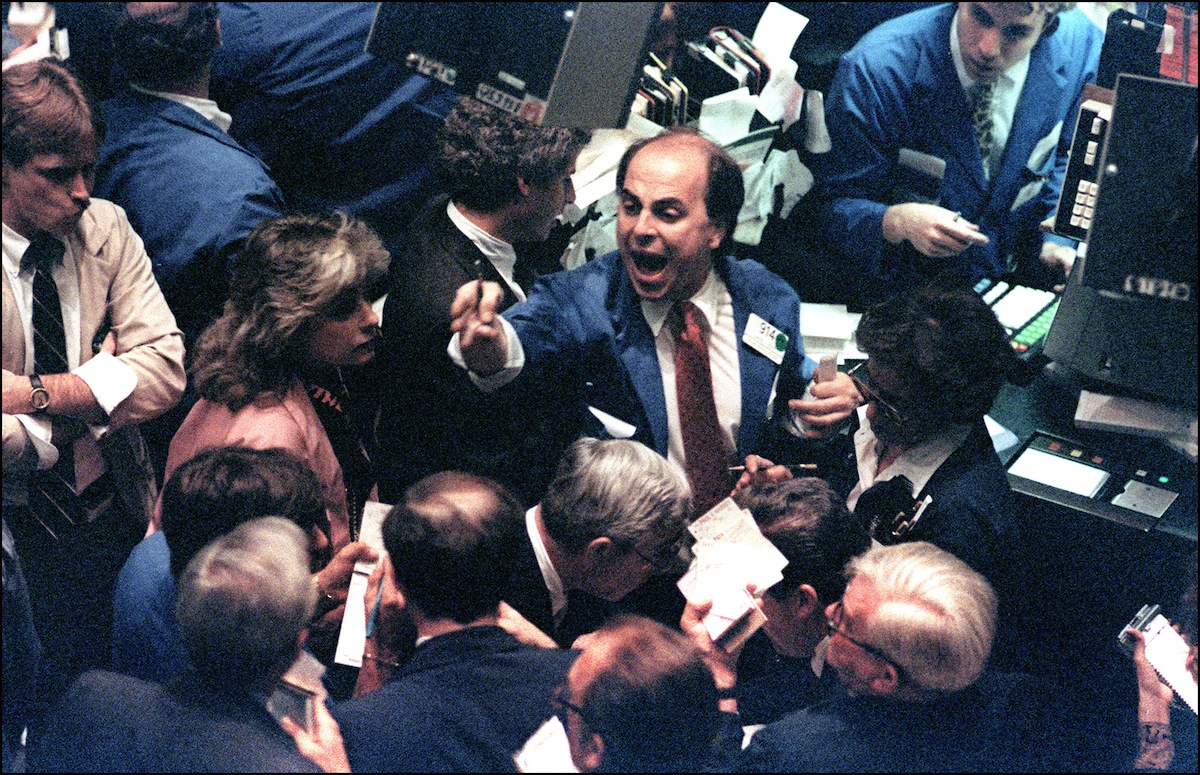

1987: Black Monday

If the meaning of the Crash of ’29 was underappreciated at the time it happened, the meaning of Black Monday 1987 was probably overblown—though understandably, given what happened. The 508-point drop in the Dow Jones Industrial Average on October 19 was, and remains, the biggest one-day percentage loss in the Dow’s history. But the reverberations weren’t all that severe by historical standards. “Almost an entire nation become paralyzed with curiosity and concern,” TIME reported. “Crowds gathered to watch the electronic tickers in brokers’ offices or stare at television monitors through plate-glass windows. In downtown Boston, police ordered a Fidelity Investments branch to turn off its ticker because a throng of nervous investors had spilled out onto Congress Street and was blocking traffic.”

Read the 1987 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: The Crash

2001: The Dot-Com Crash

The dot-com bubble deflated relatively slowly, and haltingly, over more than two years, but it was nevertheless a discrete, identifiable crash that paved the way for the early-2000s recession. Fueled by speculation in tech and Internet stocks, many of dubious real value, the Nasdaq peaked on March 10, 2000, at 5132. Stocks were volatile for years before and after the peak, and didn’t reach their lows until November of 2002. In an article in the Jan. 8, 2001, issue, TIME reported that market problems had spread throughout the economy. The “distress is no longer confined to young dotcommers who got rich fast and lorded it over the rest of us. And it’s no longer confined to the stock market. The economic uprising that rocked eToys, Priceline.com, Pets.com and all the other www. s has now spread to blue-chip tech companies and Old Economy stalwarts.”

Read the 2001 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: How to Survive the Slump

2008: The Great Recession

On Sept. 15, 2008, after rounds of negotiations between Wall Street executives and government officials, Lehman Bros. collapsed into bankruptcy. And so did AIG. Merrill Lynch was forced to sell itself to Bank of America. And that was just the beginning. TIME pulled no punches in its September 29 cover story, titled “How Wall Street Sold Out America” and written by Andy Serwer and Allan Sloan. “If you’re having a little trouble coping with what seems to be the complete unraveling of the world’s financial system, you needn’t feel bad about yourself,” the men wrote. “It’s horribly confusing, not to say terrifying; even people like us, with a combined 65 years of writing about business, have never seen anything like what’s going on. They advised readers that “the four most dangerous words in the world for your financial health are ‘This time, it’s different.’ It’s never different. It’s always the same, but with bigger numbers.”

Read the 2008 cover story, here in the TIME Vault: How Wall Street Sold Out America

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com