I reacted first to the controversy around Harper Lee’s Go Set A Watchman, from a writer’s perspective: we, of all people, shouldn’t care that a fictional character appears as a heroic crusader against injustice in one book, and as a racist in another. We should know better than anyone about drafts, and about how characters change. Even characters like Atticus Finch, who had been forever etched into our hearts (or so we thought) as the decent, brave white southern lawyer who acts on principle to help an unjustly accused black man.

I scolded my friends to this effect on Facebook, but it was in the most diplomatic version I could craft of my nearly allergic reaction to everyone’s tears over this tarnishing of Finch’s name. The actual phrase in my head as I watched the crepe being hung, was: Oh, for God’s sake everyone, grow up!

It’s quite amazing what we can hide from ourselves. It took me a few days to make the connection between my anger at the great Finch fuss, and my own father.

That man was Charles L. Black, Jr. who died in 2001, at 85. He was a white southern lawyer, admired for his work in civil rights, particularly as one of the authors of the NAACP brief in Brown V. Board of Ed. As a bonus, he looked a good deal like Gregory Peck. He was and still is revered by many, even idolized, and definitely idealized. While other girls were wishing their fathers were Atticus Finch, I was being told that mine was.

But he wasn’t, of course. He surely did great good in this world, and he could be very loving at times, very thoughtful, and notably generous. But he was also an emotionally unstable alcoholic, habitually bad-tempered and an inhibiting force in my life; I began writing at 39, three weeks after his death. The disconnect between those who didn’t know him but adored him and those of us who loved him in spite of knowing him was a destabilizing feature of my youth.

It still can throw me, though he is long gone and I am well into middle age. I have written many essays about my father, most of which are attempts to parse his complicated legacy, including a love I will always carry for him that must be able to contain complexities and contradictions, compassion and also anger. This is my life, as his daughter, and I am – this word again – allergic to discussions about my father that paint him as a saint. Not only because he isn’t one, but because no one is. Truth be told, I am allergic to all desire to believe that anyone is wholly good: it seems like an infantile kind of longing to me, one that I had to leave by the wayside decades ago.

My father was no racist, as I gather this unearthed Atticus turns out to have been. He didn’t carry evil in him. Not at all. So the analogy fails, as most eventually do. But that doesn’t keep this debate from resonating deep inside me. It doesn’t keep me from feeling dismay at the fact that people are attached to the fantasy of a perfect father, or a perfect person. And maybe that’s jealousy on my part. I don’t know.

I won’t be reading Go Set A Watchman for many reasons, but prominent among them is that I don’t need to learn that men who do much good in this wicked, wicked world of ours may not be all that they appear. That lesson is already well etched into my heart.

Robin Black is the author of Life Drawing, a novel, and If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This, a short-story collection. Her next book, Crash Course: 52 Essays From Where Writing and Life Collide, is forthcoming in 2016.

Read next: 10 Beautiful Lines From Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman

Download TIME’s mobile app for iOS to have your world explained wherever you go

See Harper Lee's Secluded Alabama Life

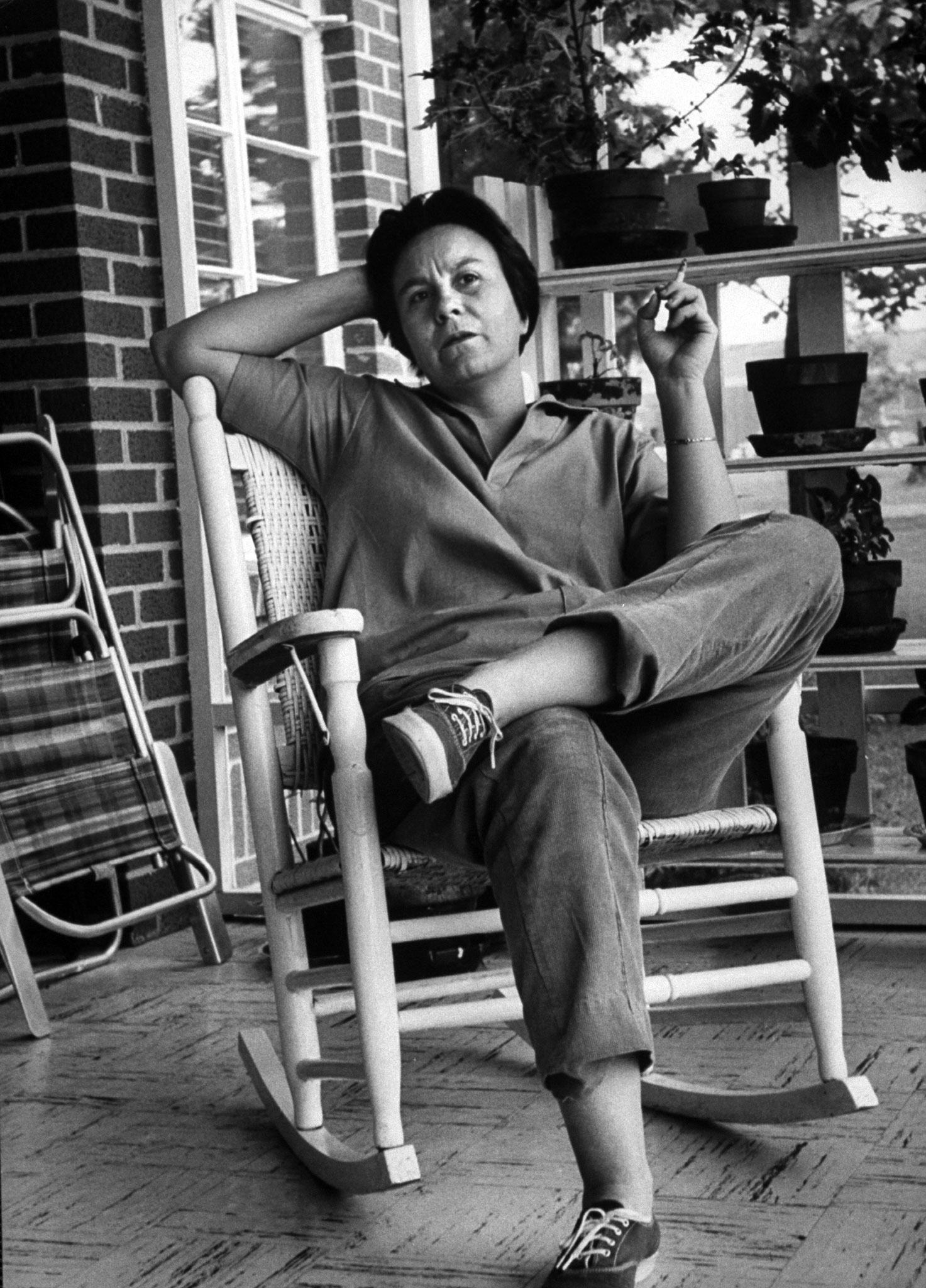

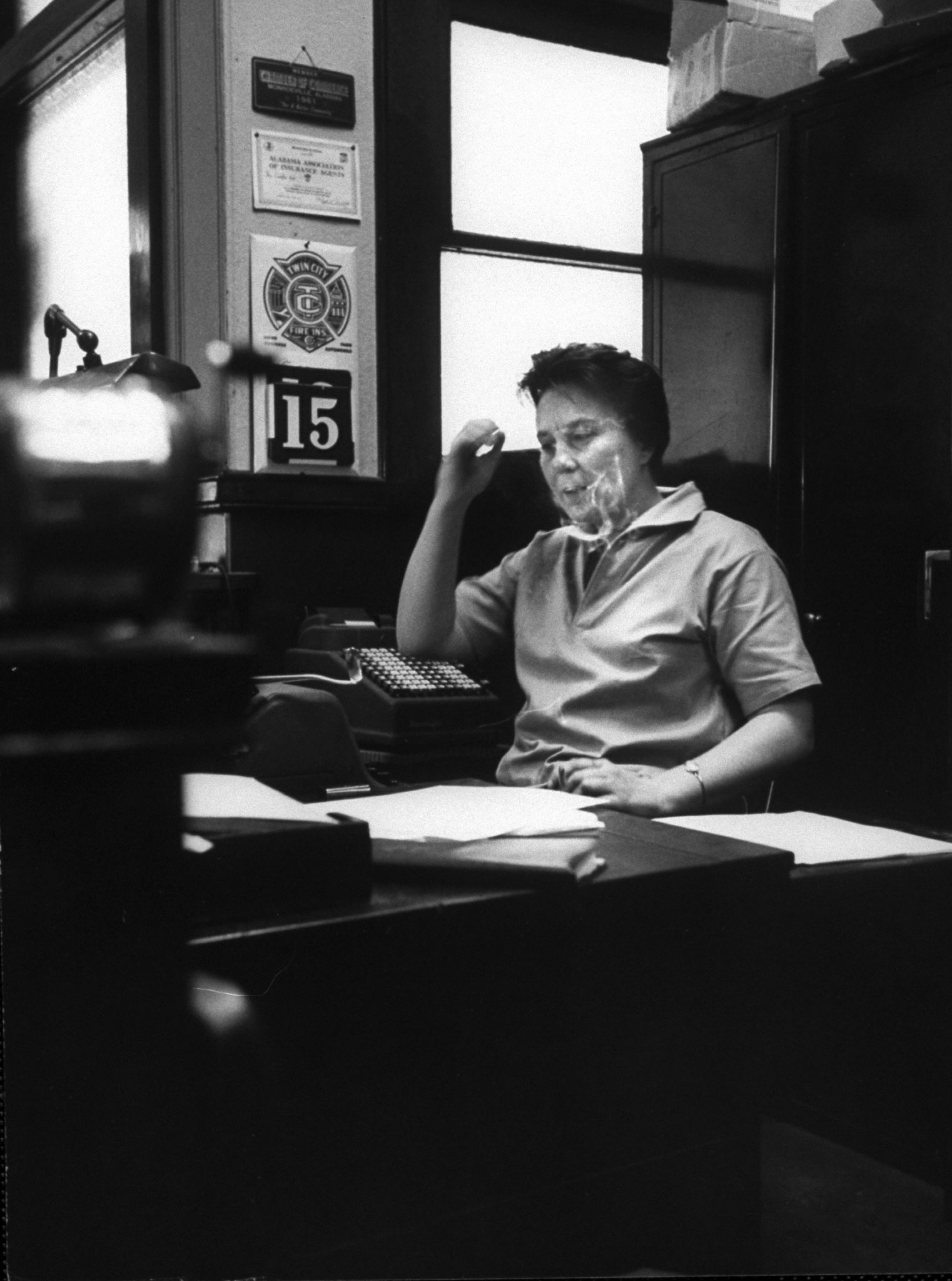

![Harper Lee [& Family] Harper Lee visiting her hometown, Monroeville, Alabama, in 1961.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150312-harper-lee-04.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com