Zócalo Public Square is a magazine of ideas from Arizona State University Knowledge Enterprise.

One of my first memories as a child in the in the 1950s was a discussion I had with my brother in our tiny bedroom in the family house in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. We had heard in school about a planet called Pluto.

Pluto was the farthest, coldest, and darkest thing a child could imagine. We guessed how long it would take to die if we stood on the surface of such a frozen place wearing only the clothes we had on. We tried to figure out how much colder Pluto was than Antarctica, or than the coldest day we had ever experienced in Pennsylvania. Did the surface of Pluto have mountains, frozen ponds like the ones we loved to skate on, or acres of snow to play in and build snowmen?

Pluto—which famously was demoted from a “major planet” to a “dwarf planet” in 2006—captured our imagination in a way that even Mars (a possible abode of life) and glorious, ringed Saturn couldn’t. It was a mystery that could complete our picture of what it was like at the most remote corners of our solar system.

Photographing Pluto: This Is How New Horizons Works

Pluto’s underdog discovery story is part of what makes it so compelling. Clyde Tombaugh was a Kansas farm boy who built telescopes out of spare auto parts, old farm equipment, and self-ground lenses. In 1928, he sent drawings of Jupiter and Mars to Lowell Observatory, a premier observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, to ask for a job as an assistant. At first, the observatory rejected his request, but Clyde showed persistence, and eventually got a job.

The observatory’s founder, the astronomer Percival Lowell, believed there existed a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune, so Tombaugh’s task was to search among millions of stars for a moving point of light. He used a device called a blink comparator, which compared two photographs of the sky taken at different times, so that a moving target, such as a planet, could be seen flitting back and forth against a background of fixed stars.

On February 18, 1930, Tombaugh found Pluto. It was the first planet discovered by an American, and represented a moment of light in the midst of the Great Depression’s dark encroachment. The planet’s name, referencing the Greek god of the underworld, was suggested by an 11-year old British girl. (The cartoon dog was named later.)

For decades, Pluto thrived in its role as the ninth major planet of our solar system, even though it was tiny compared to the others (just one-fifth the diameter of Earth) and so far away (on average, about 3.6 billion miles from the sun and 1 billion miles from Neptune, its closest planetary “neighbor”).

But then, in 1992, two astronomers discovered another planet-like object beyond the orbit of Neptune. Six months later, they discovered a third object. It looked like Pluto might actually be a member of a sort of asteroid belt, similar to but way beyond one we’ve known about for a long time between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

At this point, the scientific community began to wonder whether the tiniest planet was going to keep its rarefied title. Would it suffer the same fate as Ceres, the first and largest asteroid discovered in 1801, which reigned as a planet for decades before it was demoted? Despite this concern, a core group of scientists and engineers, me included, was working on convincing NASA to send a probe to our solar system’s last unexplored planet.

By the turn of the millennium, dozens more objects beyond Neptune like Pluto had been discovered, including one that might even be larger than Pluto. So, in August 2006, the International Astronomical Union elected to demote the planet. It now shares its dwarf planet designation with Ceres and three other of the 1,200 bodies that have been located beyond Neptune, collectively known as “Kuiper Belt Objects.”

This demotion came just seven months after we’d successfully launched the NASA New Horizons spacecraft. When I heard this sad announcement, I felt as if I’d lost an old childhood friend.

But Pluto’s scientific interest to those of us on the New Horizons team didn’t diminish. The Kuiper Belt is still an interesting place: It’s populated by icy bodies that are remnants of the solar system’s formation 4.6 billion years ago. These are the building blocks of planets, and they are still around for us to examine.

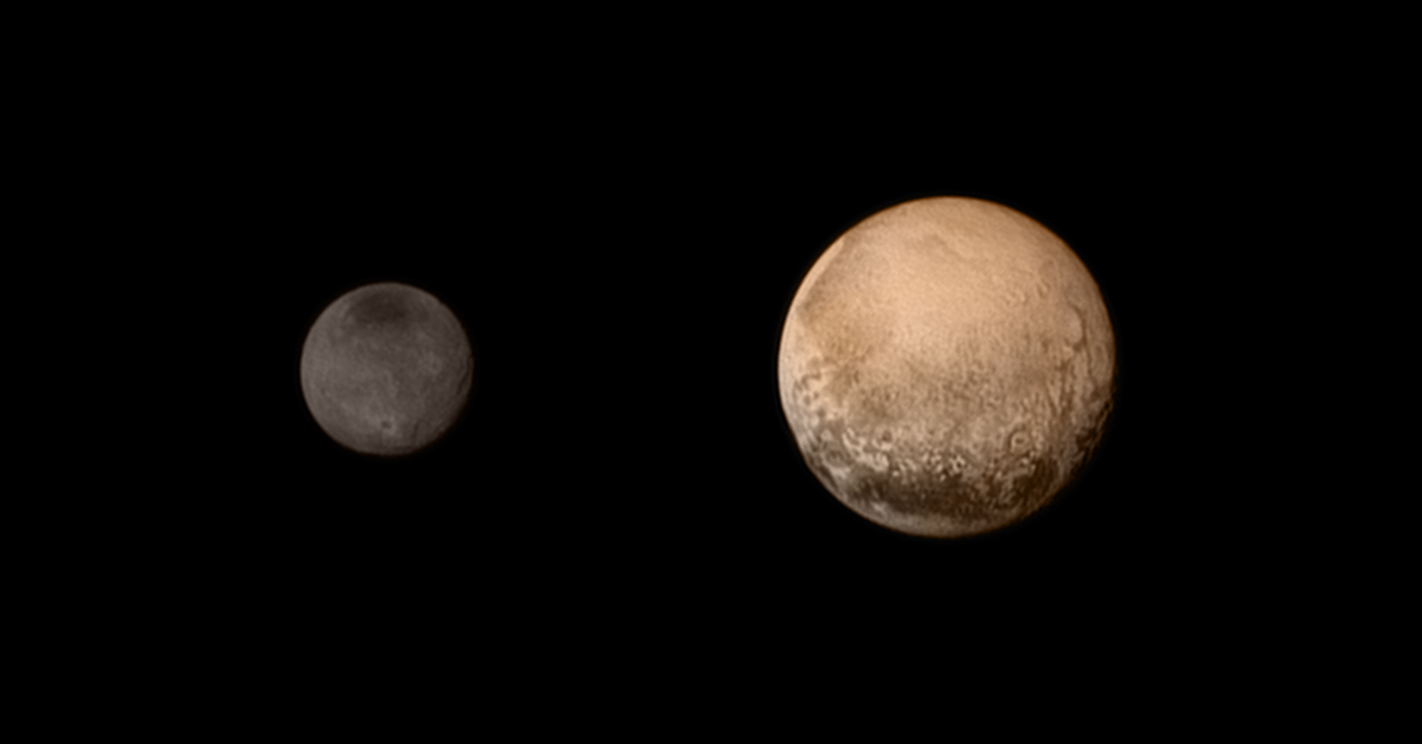

The few clues scientists have been able to gather about Pluto so far are tantalizing. We know its surface contains ices composed of methane, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and other compounds familiar to us. It has some very dark regions, but it also seems to have a bright polar cap, like on Earth. Its atmosphere is very thin, but it’s composed largely of nitrogen, like our own. And we believe Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, was formed the same way as our moon, by coalescing from the debris left over from a massive impact by a rogue body.

So, all of us scientists are hoping that the close-up looks we are finally getting now of this dwarf planet can tell us how the chaos that reigned at the beginning of the solar system could have created objects so similar and yet so foreign as Earth and Pluto.

It’s taken nine years of travel, but we’ll finally get within 7,800 miles of Pluto Tuesday. Our spacecraft will enable us to see features as small as a football field. I’ve been painstakingly observing Pluto through a large telescope for over 15 years, seeing what I think is frost moving around on its surface with the seasons. I hope to see it more clearly as the data come in.

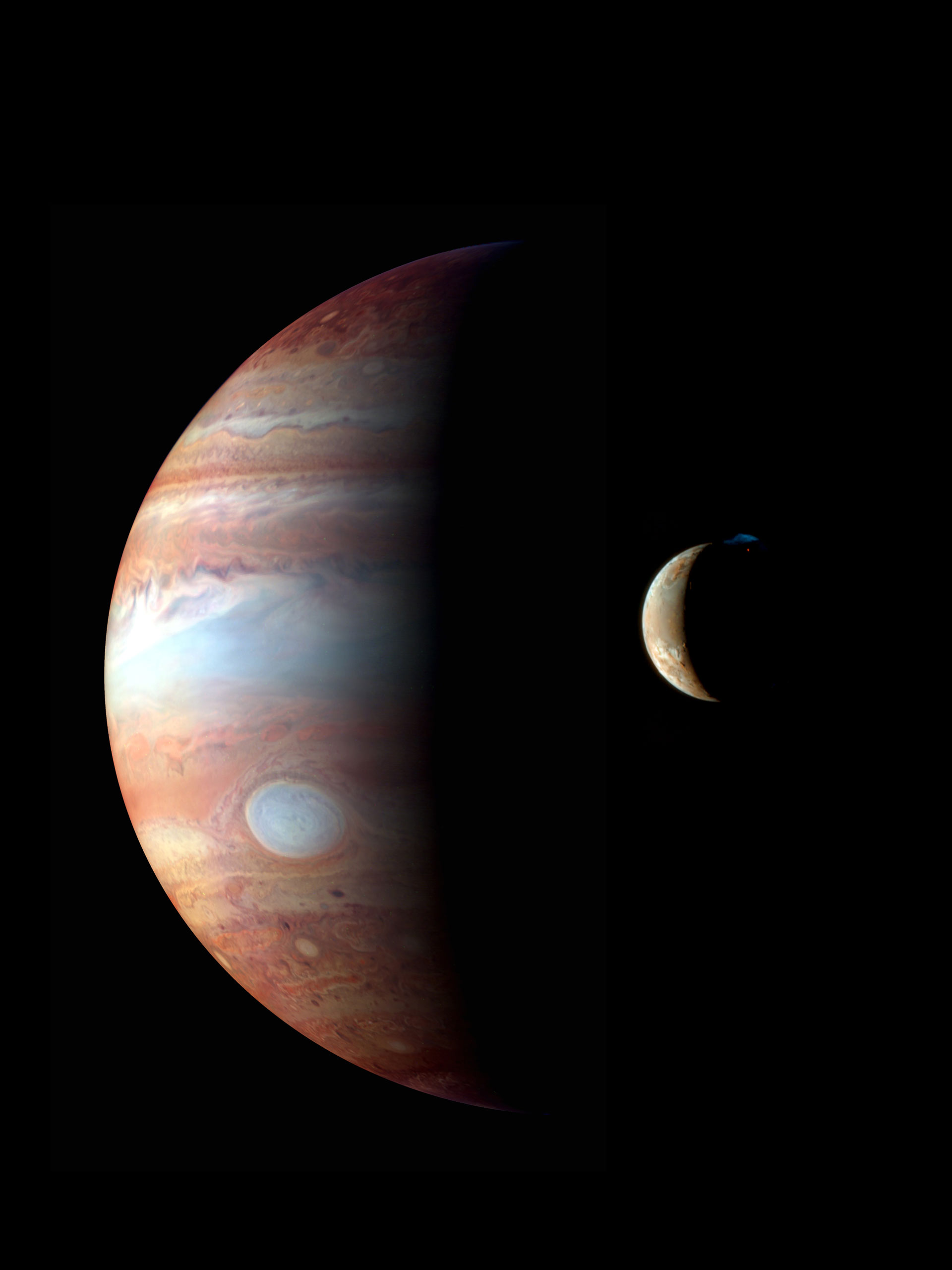

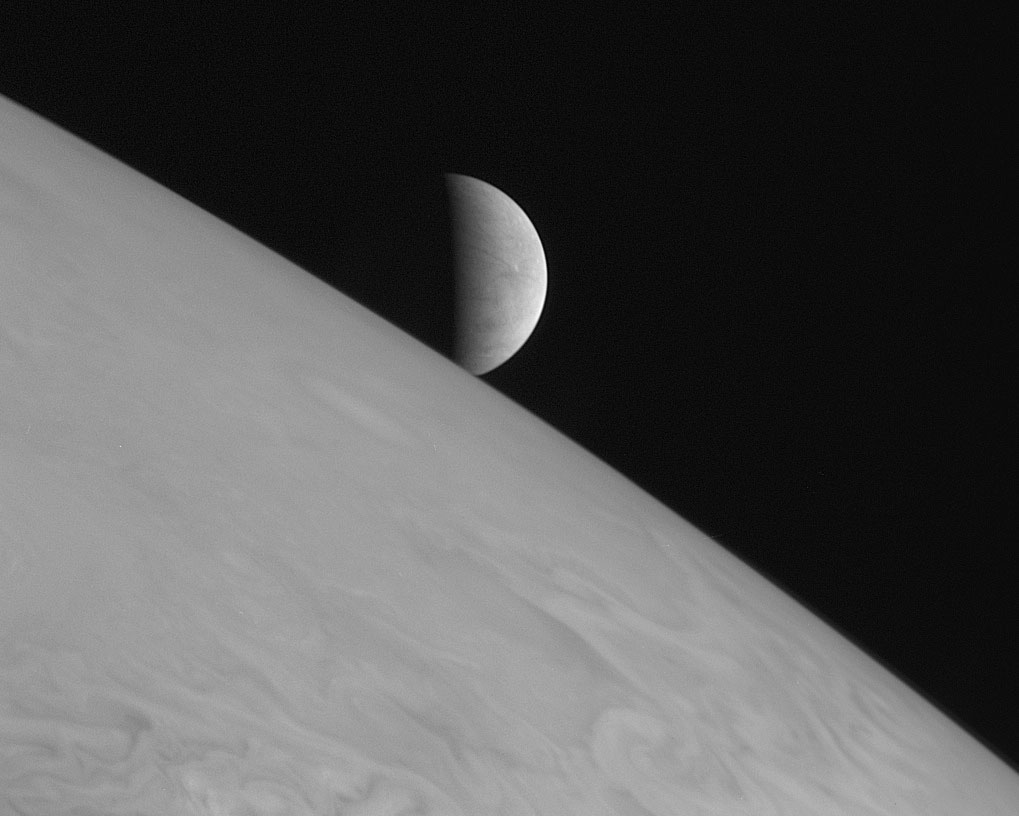

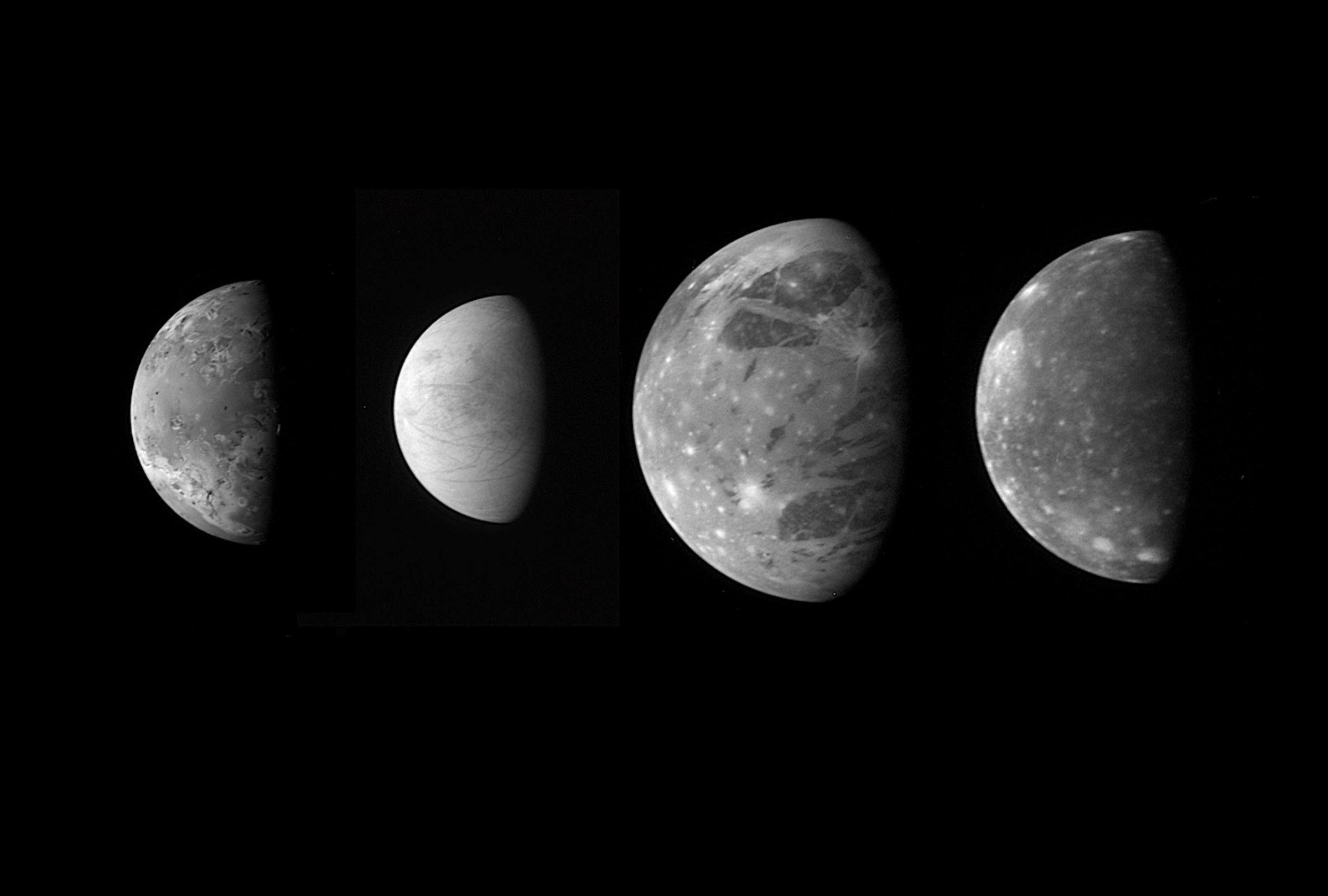

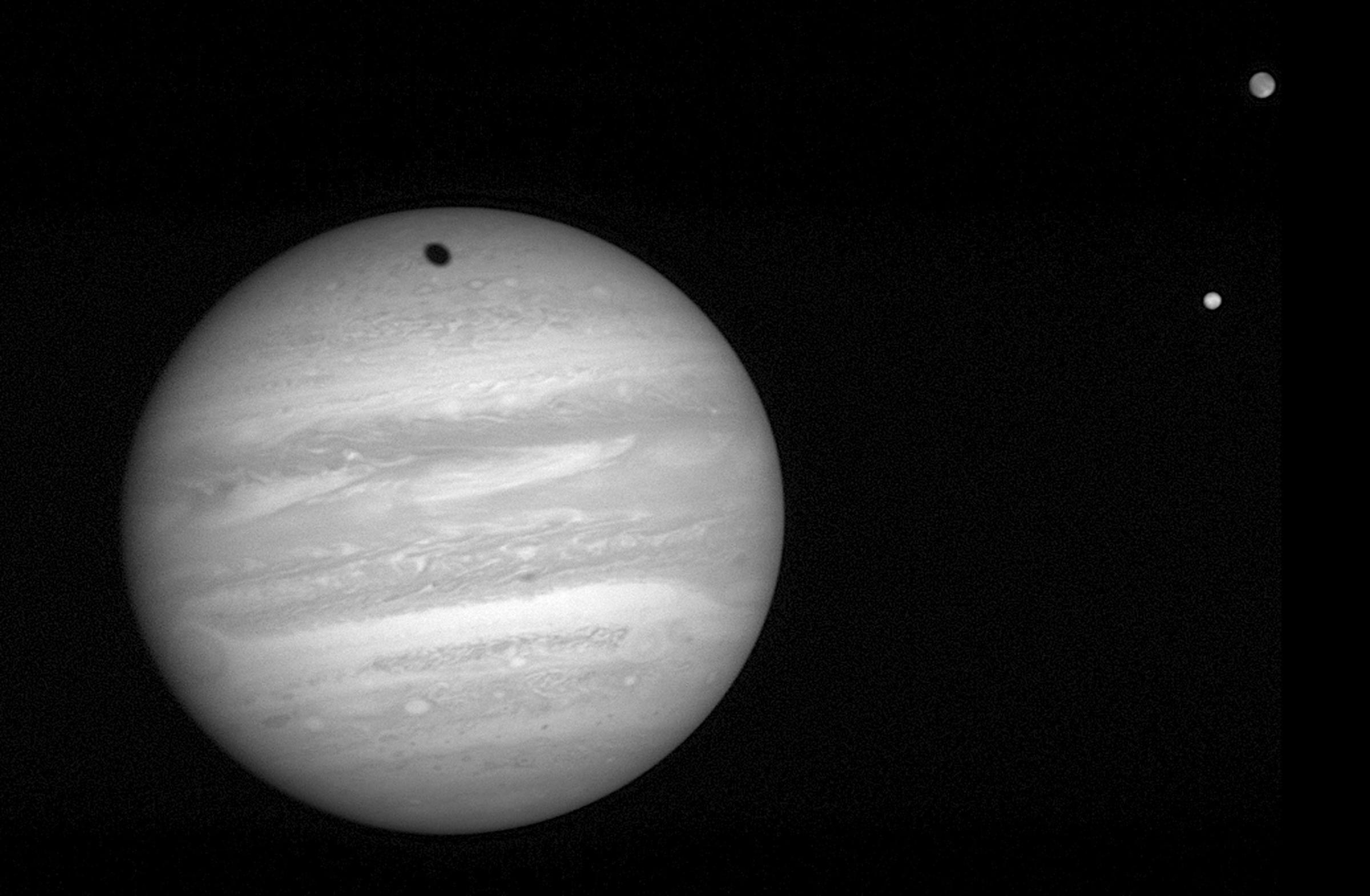

As we bear down on Pluto, all of us scientists are just as curious as I was in my childhood bedroom, wondering what Pluto is like. Is its surface old and cratered, or does it have shifting polar caps like the Earth’s that indicate recent activity? Does it have volcanoes like Jupiter’s moon Io, plumes like Neptune’s moon Triton, or water geysers like Saturn’s moon Enceladus? Will it just be like the objects around it, or will it have some unique quality that earns back the special place it once had in everyone’s hearts?

Pluto is much more than something that is not a planet. It’s an underdog we’re still cheering for. It’s a reminder that there are many worlds out there beyond our own—that the sky isn’t the limit at all. We don’t know what kinds of fantastic variations on a theme nature is capable of making until we get out there to look.

Bonnie Buratti is a principal scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a member of the New Horizons science team. She divides her time between New Horizons and Cassini, a mission currently in orbit around Saturn.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com