In 2013, when the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology revised the guidelines that doctors use to decide which patients need cholesterol-lowering treatment for heart disease and which do not, there was more confusion than confidence in the new advice. Now, a new study published in JAMA may offer some answers about the effects of the updated treatment guidelines.

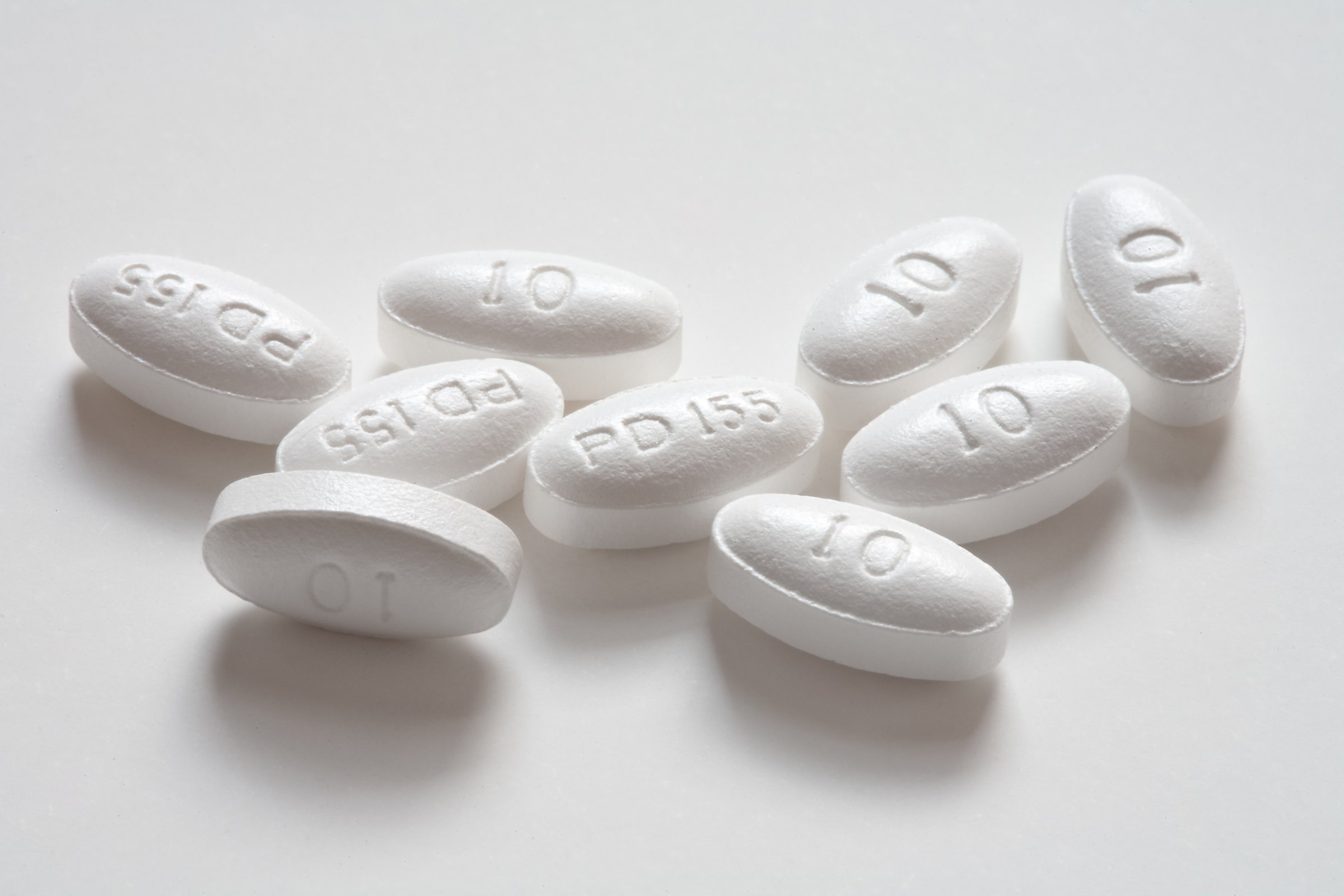

Rather than setting threshold levels of target cholesterol levels that were considered normal or high, for example, the new guidelines instead assessed a person’s overall risk of having a heart attack, stroke or other heart problem over the next 10 years. If these factors—which included cholesterol, family history of heart disease, age and other factors—contributed to a risk of 7.5% or higher, then the person would be eligible for taking the cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins, which not only bring potentially troublesome fat levels in the blood down but also reduce inflammation, which can contribute to atherosclerosis and set the stage for a heart attack.

MORE: Should I Take a Statin? What You Need to Know About the New Cholesterol Guidelines

Heart experts weren’t all convinced that putting more people on statins would actually lead to fewer heart events. Their biggest concern was that the looser criteria would mean more otherwise healthy people who wouldn’t really benefit from statins would be taking the drugs. (Some estimates showed that as many as 12.8 million more people would be taking the medications under the new guidelines.). So Dr. Udo Hoffman, director of the cardiac MR, PET and CT Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and his colleagues decided to analyze the data to see if the new guidelines really were contributing to less heart disease.

In the new study, they compared 2,435 people who were the offspring or third generation descendants of the Framingham Heart Study, the pioneering heart disease trial that continues to follow people and track their lifestyle and health outcomes. Some of the participants in the current study were at higher risk of heart disease, and some were not. Using the older cholesterol-based heart risk guidelines, Hoffman found that 14% would have been given a statin. Nearly three times that proportion, 39%, would have qualified under the new 2013 guidelines.

MORE: New Guidelines for Cholesterol Treatments Represent “Huge Change”

When the researchers looked at how many of those people who were eligible to take statins went on to have heart events, it was more than twice as high using the newer guidelines. That means that a higher proportion of people who should be on statins, according to the newer guidelines, went on to have heart events, suggesting that the new criteria were better at predicting which people were at higher risk.

In addition, Hoffman also backed up his findings with tests of the amount of calcium in the heart vessels of the participants. Coronary artery calcium tends to be a good indicator of how stiff the vessels are becoming; more calcium suggests more atherosclerosis and therefore a higher risk of heart attack or other issues.

MORE: Statins May Seriously Increase Diabetes Risk

The findings were especially robust in those people considered to be at intermediate risk of heart disease—patients in the grey area where it’s not entirely clear how likely they are to have heart problems. Among them, those who qualified to take statins under the newer 2013 guidelines were nine times more likely to have a heart event than those who didn’t meet the criteria for needing the drugs. “If we looked at this group from the formal risk factor evaluation approach [using the older guidelines] there is no way we could guess which of these people were at higher risk of heart events,” says Hoffman. “So in this population, the new guidelines are helpful.”

The findings show that even if the revised guidelines cast a wider net of people who would be on statin drugs, the rate of heart events the new criteria are picking up remain about the same. That means that the people being captured are still those at higher risk of having events, and not healthy people who would be unnecessarily put on medications, as some critics of the new guidelines feared. “Overall, the new guidelines are a more accurate and efficient allocation of statin therapy,” says Hoffman.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com