What happened?

There is a simple answer: a preterm birth. A premature baby.

My daughter is a preemie. That sounds common enough, even kind of cute.

I was a preemie, too. My mother can’t recall how early, maybe four or five weeks. Early enough that as she was being rushed into the delivery room, she was so distraught that a nurse told her not to worry, that her own child had been born early, too, and was just fine.

Then comes the laugh line: My mother sobbed, But—is your kid smart?

At this point in the storytelling, my mother would shake her head. “Can you believe it? That nurse should have slapped me.”

And we would laugh. There I stood, sound of body, brain apparently intact.

What happened?

Five and a half months into my second pregnancy, I woke up in labor—sudden, unexplained labor—and my daughter was delivered via emergency cesarean.

In recent years, I think I’ve read in passing about some increase in the incidence of premature births, in the level of prematurity. I think I’ve read about the astronomical costs and extraordinary interventions involved in caring for such babies. I probably wondered to myself, without dwelling on it for long, whether all of them truly ought to be saved.

I’ve heard of babies so tiny they can fit in the palm of your hand. I’ve seen those photos somewhere. The NICU here has one taped to the door: a baby nestled in a cupped palm, sepia-toned, serene and perfect. Just like a regular baby, only in miniature.

My daughter looks nothing like that.

She’s pre-premature. She’s pre-alive.

Then again, the books displayed in the NICU list a category for a baby like her: “extremely premature.” These books chart the probabilities of outcomes for each category of preemie, from “mildly premature” to her category: the odds of death, of major complications, of serious disability.

Her official gestational age is 25 weeks and three days. In terms of her odds, every one of those days matters. But we never had any certainty about her due date.

One of the books has no row for cases more extreme than hers. It also notes that, until recently, a preemie like her had virtually a zero percent chance of survival. This book distinguishes itself from other books for parents of preemies as the one with a “positive approach.”

Most of the charts list 1,000 grams as the lowest cutoff. My daughter has already dropped below her birth weight of 705 grams, and she is dropping lower by the hour.

Eventually, I find charts that include rows for babies born at 24 weeks, 23 weeks, even 22 weeks and under, but then there are no statistics, only words in parentheses: poor outcome, insufficient data, N/A.

Or blank spaces.

What happened?

Maybe it’s an unproductive question, an unseemly question, a petty question. As patiently as they can, the doctors attempt to dispel it from their higher realm.

If I’d arrived at the hospital sooner, wouldn’t my daughter have been safe?

“You were fully dilated when you got to triage,” Dr. Bryant, my obstetrician, says.

But if I’d arrived twenty minutes earlier, one hour, three hours—

“The baby was coming out,” she says.

My husband Peter fixates on the grimy suitcases he hefted up from the basement in preparation for the renovation. All evening, I was overtaken by fits of sneezing, but it had already been a terrible allergy season.

“It wasn’t the suitcases,” Dr. Bryant says. “It wasn’t the sneezing.”

Then was it that my pregnancies were so close together?

Dr. Bryant says that an interval of less than six months between pregnancies is considered risky. The interval between mine was at least eight.

Was it that Peter and I made love that night?

Gently, firmly, Dr. Bryant shakes her head.

Then what happened?

“It happens,” Dr. Bryant says. “In my decades of practice, I’ve known this to happen.”

When we ask Dr. Kahn, she says, “Well, someday someone will win a Nobel for figuring out the answer to that.”

The general prevailing theory, she says, is that, for some reason, the baby needed to come out.

Something went wrong and we all missed it. Something so wrong that my daughter exited my body before her skin could hold itself together, before her brain could withstand the trauma, before she could nurse, before she could breathe.

What happened?

Did I deliver a child or lose one?

Do I keep holding on or do I prepare to let go?

“Two things that happened in 2012,” AOL CEO Tim Armstrong declares at a town hall meeting one year after my daughter has come home from the hospital, the same week she takes her first steps. “We had two AOLers that had distressed babies that were born that we paid a million dollars each to make sure those babies were okay in general. And those are the things that add up into our benefits cost. So when we had the final decision about what benefits to cut because of the increased health care costs, we made the decision, and I made the decision, to basically change the 401(k) plan.”

On his own computer screen, my husband watches the headlines proliferate, from Capital New York (ARMSTRONG: “DISTRESSED BABIES FIGURED IN 401(K) ROLL-BACK) to Fortune (ADD TIM ARMSTRONG’S “DISTRESSED BABIES” TO THE PILE OF GAFFES) to Daily Kos (BREAKING! THERE’S STILL AN AOL, AND ITS CEO IS STILL AN A-HOLE).

On Twitter, “distressed babies” is becoming a meme:

“How many distressed babies does AOL pay this guy?”

“I hope these ‘distressed babies’ are happy.”

On the overhead TV screens throughout the newsroom, Peter watches close-ups of Armstrong rotate among playbacks of the CEO’s previous blunders. On cable news shows, talking heads debate health care costs, privacy laws, the Affordable Care Act, corporate responsibility, crisis management, potential legal and civil liabilities, AOL stock prices—all in the context of “distressed babies.”

His own newsroom gawks and titters at the spectacle. A number of Peter’s colleagues—editors, writers, PR flacks—knock on his door to gossip: Can you believe this? What an idiot.

One of the first reports—by Re/code’s Kara Swisher, a prominent tech journalist—inaccurately summarizes Armstrong’s town hall comments as referring to “the difficult and costly pregnancies of two employees,” as if “distressed babies” could only be the result of such circumstances. All the subsequent speculation focuses on “AOL moms.” None of the experts challenge these assumptions. None of the commentators seem to consider the possibility that one of the employees in question could be a father.

Except for those of Peter’s coworkers who know the barest outlines of our daughter’s arrival and immediately identify Mila as one of those “distressed babies.” The sympathetic ones come by Peter’s office to express recognition of his uncomfortable position. Hey, he’s talking about your kid, right? How’s she doing? How are you?

The next day, the media uproar over “distressed babies” continues at a fever pitch. More talking heads, more commentary, more analysis, more tweets. Instead of a public apology, Tim Armstrong issues an internal memo, which is leaked to the media almost immediately:

“As we discussed at the town hall, we care about you and the company—a lot…In that context, I mentioned high-risk pregnancy as just one of many examples of how our company supports families when they are in need…As I have said over and over again, our employees are our greatest asset. Let’s move forward together as a team.”

The cold slap seeps in. With each clarification that Tim Armstrong issues, our family seems more and more at fault somehow, and our daughter’s humanity seems less and less evident.

Ever since my daughter’s arrival, my shame and guilt seem to have taken up permanent residence in my body along with my organs and bones, as fixed and familiar as they are unseen and unexamined. Likewise, my sense of being a burden, of encumbering others because of my failure to hold on to my own baby, has become the hidden pulse of my daily existence.

Somehow Tim Armstrong has managed to broadcast those innermost feelings at a companywide meeting before they became fodder for the twenty-four-hour news cycle. And now that those feelings are out there for the world to digest, I can finally take a closer look at them myself.

What did I do wrong other than experience a medical emergency?

What resources did my daughter use other than the health insurance that my husband and I purchased?

How did Tim Armstrong and his corporation extend themselves for my family other than by complying with the basic terms of our benefits?

Distressed babies. I know about “distressed jeans” and “distressed leather.” I’ve heard the terms distressed securities and distressed properties. Or distressed merchandise: damaged goods.

“Distressed babies” sounds like another bit of corporate-speak, except that I doubt it shows up on any MBA vocabulary list. It’s both a dehumanizing insult and a strange euphemism that seems intended to demonstrate extra sensitivity on the part of the speaker—as opposed to, say, premature babies or sickly babies or g-ddamn pain-in-the-ass babies.

It aims for a show of sympathy while positioning the speaker as the hero of this scenario. It brings to mind a fussy infant wailing to be picked up rather than a child fighting for every minute of her life.

Distressed babies that were born that we paid a million dollars each to make sure those babies were okay in general.

After all these months of struggling to say those words myself—she was born—now Tim Armstrong has said them for me, in a context that suggests that she probably shouldn’t have been. Babies that were born. “That,” not “who.”

We paid a million dollars. Did he personally pay her bills? After all my dealings with the insurance company, this is news to me.

To make sure those babies were okay in general. Did he demand some guarantee from the doctors that I never received? Does Mila count as “okay in general” now? If not, should she be written off as a bad investment?

I tell myself that people make mistakes. But I can’t pretend that these off-the-cuff remarks don’t reveal a damning, perhaps unconscious judgment of me and my daughter.

Even if I accept that Armstrong’s intention was not to scape-goat those babies but to point out his pride in having paid for their care—an apparently exorbitant expense that somehow drained AOL’s coffers to the point that he was forced to recoup it from another component of employee benefits—that judgment just became explicit in his assumption that “distressed babies” must be the result of “high-risk pregnancies.” Which no one in the media has questioned, either.

The implication is that our baby was a risky proposition from the start, and therefore her care was optional. We selfishly claimed more than our fair share of health benefits, and Tim Armstrong and AOL bailed us out. The medical treatment that saved our daughter’s life was not a basic right or even a contractual obligation, but an act of corporate charity and proof of Tim Armstrong’s personal generosity. And Peter’s co-workers have only us to blame for those cuts to their retirement savings.

I reach for Peter’s hand. I tell him that if he can move on as if this never happened, I can, too. Peter says that if that’s what I want, he can. We go back and forth, around and around.

At last, Peter says, “I guess I can’t.” His anguish is plain on his face.

Ever since our daughter’s arrival, my rawer emotions and overt trauma have often taken precedence over his. Sometimes, I remind myself, my husband needs rescuing, too.

When I sit down at my desk, it’s past midnight. My hands are trembling and my heart is pounding, but my head feels very clear.

Thirteen months ago, my daughter left the hospital and never looked back. I’m the one living as if I’m trapped behind walls of glass.

If I don’t come forward as the mother of my baby, I might as well forsake her. If I don’t reclaim her story, I might as well label her a burden, a tragedy, a creature who shouldn’t exist.

So I write. All the details that have seemed unspeakable, I write.

I’m the mother of one of those “distressed babies.” I’m the reason the CEO of a large corporation felt the need to cut benefits.

A million dollars. At this point, I have no way of knowing if Tim Armstrong and AOL actually paid that amount, though this accounting certainly doesn’t square with my rudimentary grasp of how insurance works. I understand that a CEO might have a different approach to valuation of a human life than, say, a mother. But I’m not sure, in the final accounting, how many of us could survive such a calculus.

Would it have occurred to Armstrong to single out the medical expenses of an employee who survived a car crash, or needed heart surgery, or got breast cancer?

For the first time, it occurs to me that when Dr. Kahn described Mila’s birth as catastrophic, she meant the word in the medical sense. A catastrophic medical event is, almost by definition, unforeseeable and unpreventable.

Yes, our daughter needed costly intensive care. Yes, we are grateful—indelibly grateful—that our employer-subsidized plan covered most of the expenses.

But isn’t that the whole point of health insurance?

At last, I describe Mila’s first steps, those two tiny steps that she took in the days leading to Tim Armstrong’s town hall meeting. And I finally use the word that, for me, might be the most dangerous word of all.

Miracle.

I don’t mean that my daughter emerged from her birth completely unscathed. I don’t mean that she is an act of divine intervention more than a person. I don’t mean that she has to be a miracle—or even “okay in general”—in order to justify her existence.

She is a miracle in the way that any child taking her first steps is a miracle. And yes, she deserves a little extra credit. Some recognition of her strength, not only her suffering; of her resilience, not only her damage.

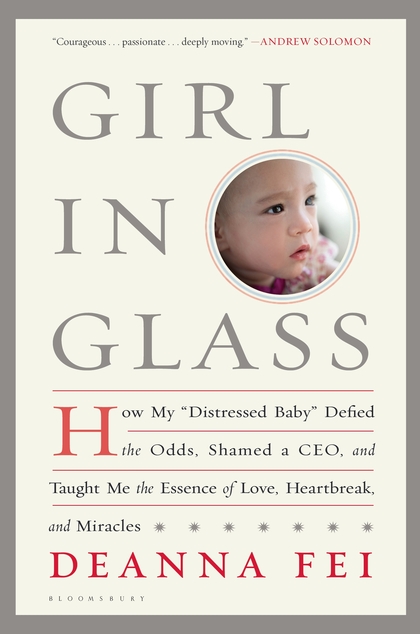

Excerpted from Girl in Glass: How My “Distressed Baby” Defied the Odds, Shamed a CEO, and Taught Me the Essence of Love, Heartbreak, and Miracles, by Deanna Fei.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com