In baseball, not all pioneers are created equal. Some, like Jackie Robinson, are recognized immediately as formative figures whose impact reverberates forever, in the game and throughout society. Others, though, need some time — and distance — for their contributions to resonate.

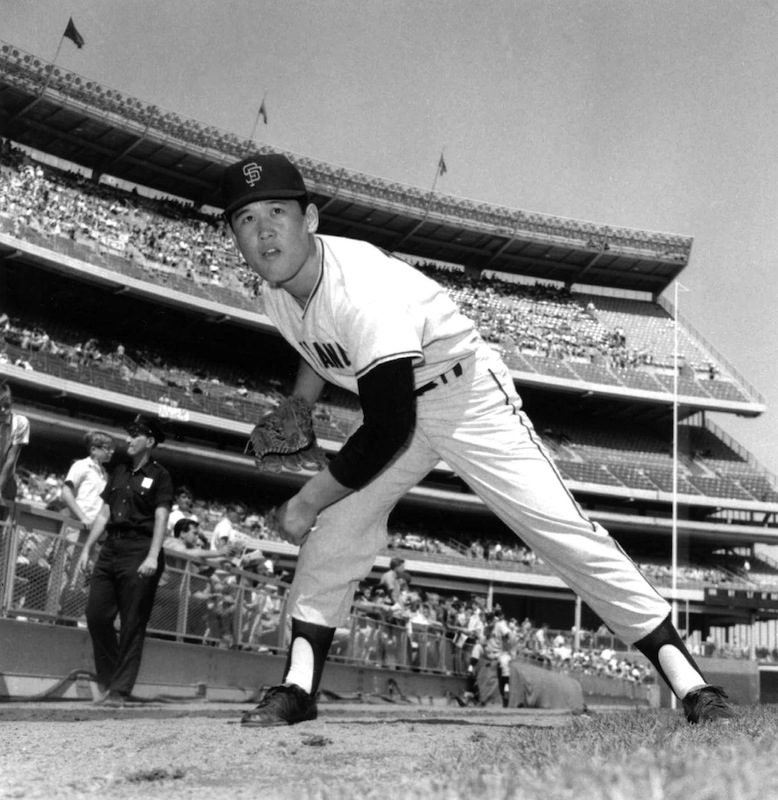

Masanori Murakami, the first Japanese person to play in Major League Baseball, is decidedly in the latter category.

“For a long time, he was kind of a footnote in history. He was a trivia-question answer,” says author Robert K. Fitts, whose biography Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer was released in April. “But he was a true hero.”

This week, Fitts and Murakami will be in Cincinnati for Murakami to take part in celebrating the 2015 MLB All-Star Game. But on July 2, they had a special stop on their itinerary: Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets. Murakami threw out the ceremonial first pitch from nearly the same spot that he changed baseball 51 years ago.

In 1964, Murakami, a 20-year-old pitcher for the Nankai Hawks, was in America on a kind of cultural exchange program with the San Francisco Giants. He was called up from the Giants’ single-A team in Fresno on Aug. 30, joined the team in New York, and on Sept. 1 came in as a late-inning reliever for against the Mets at Shea Stadium. History was made.

Mashi (as his teammates called him) was only on the mound for one inning in the Giants’ 4-1 loss, but he so impressed the team with his control and efficiency that he remained on the roster for the rest of the season. He was also an immediate fan favorite, with Mashi Mania spreading across the Bay Area.

“When I was here in ‘64, I felt like baseball was a little lighter, much more fun,” the now-71-year-old Murakami remembers. “In Japan, there’s all this calculation and control and I felt like it was maybe a little bit dark. So here, I had more freedom to play baseball and enjoy it the way that I loved.”

He pitched out of the bullpen eight more times in 1964, and saw action in 45 games the next season. With each throw, Mashi further legitimized Japanese baseball in the eyes of Americans.

“Until he appeared at the major league level, the general supposition among fans and baseball professionals was that the Japanese professional league was the equivalent of double-A at best,” John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, says. “After Murakami, that was impossible.”

But, just as quickly as his American career began, it came to a halt. A nasty contract battle between the Giants and Hawks resulted in Murakami’s return to Japan and a fundamental reevaluation of Japan’s relationship with Major League Baseball. If Japanese players could compete with Americans, the thinking went in Japan, then they ought to stay at home and build the reputation of their own game. “I think the Japanese professional baseball leagues did not want to become just a source of raw materials,” Thorn says. “They protected their best players with much more vigor afterwards.”

The door Mashi so improbably opened slammed shut for other Japanese players — and it stayed sealed for 30 years. The name Masanori Murakami was forgotten; a trailblazer was reduced to trivia.

In 1995, things began to change.

Hideo Nomo, at 26 one of Japan’s best pitchers, exploited a contractual loophole that freed him to play in America by retiring in Japan. He promptly ended his Japanese career, signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers, and became an immediate sensation.

“I was very happy to see another Japanese player finally make it to the major leagues after all of these years,” Murakami told a Japanese reporter after Nomo’s debut on May 2, 1995. “Nomo’s performance today brought back a lot of fond memories for me. My heart was pumping for him.”

Nomo won National League Rookie of the Year in 1995, threw the first of two career no-hitters in 1996, and ultimately played in America for 13 years. His success cracked the wall separating Japanese players from the U.S., and it drew American attention to Murakami for the first time in decades. In Mashi, fans discovered the pitcher who made Major League Baseball take Japanese pros seriously, who made Nomo’s jump to America possible, who inspired a generation of Japanese Americans unaccustomed to seeing themselves represented in a predominantly white culture.

“I was born and raised in San Francisco and was only 8 years old when he played here,” Facebook user Wayne Yoshitomi said in a post on the Mashi fan page. “I didn’t realize until later in life how important it was to have someone that looked like you playing in a professional sport.”

Today, Japanese representation in Major League Baseball has become something we expect. More than 40 players have followed Nomo from Japan since 1995, including bona fide superstars like Ichiro Suzuki, Hideki Matsui and Yu Darvish. In turn, Murakami’s standing grows, albeit slowly. But his place in baseball history is secure — even if it took decades for the force of his accomplishments to finally be felt.

“We were comparing him to an Asian Jackie Robinson in the majors,” says 17-year-old Philip Choi, who was in the stands for Mashi’s Citi Field pitch. “Because he’s the first, he still has a lot of impact. First everything is good—and the first Japanese player, especially with all the Japanese players in the league now, is huge.”

Dante A. Ciampaglia is a writer and editor living in New York

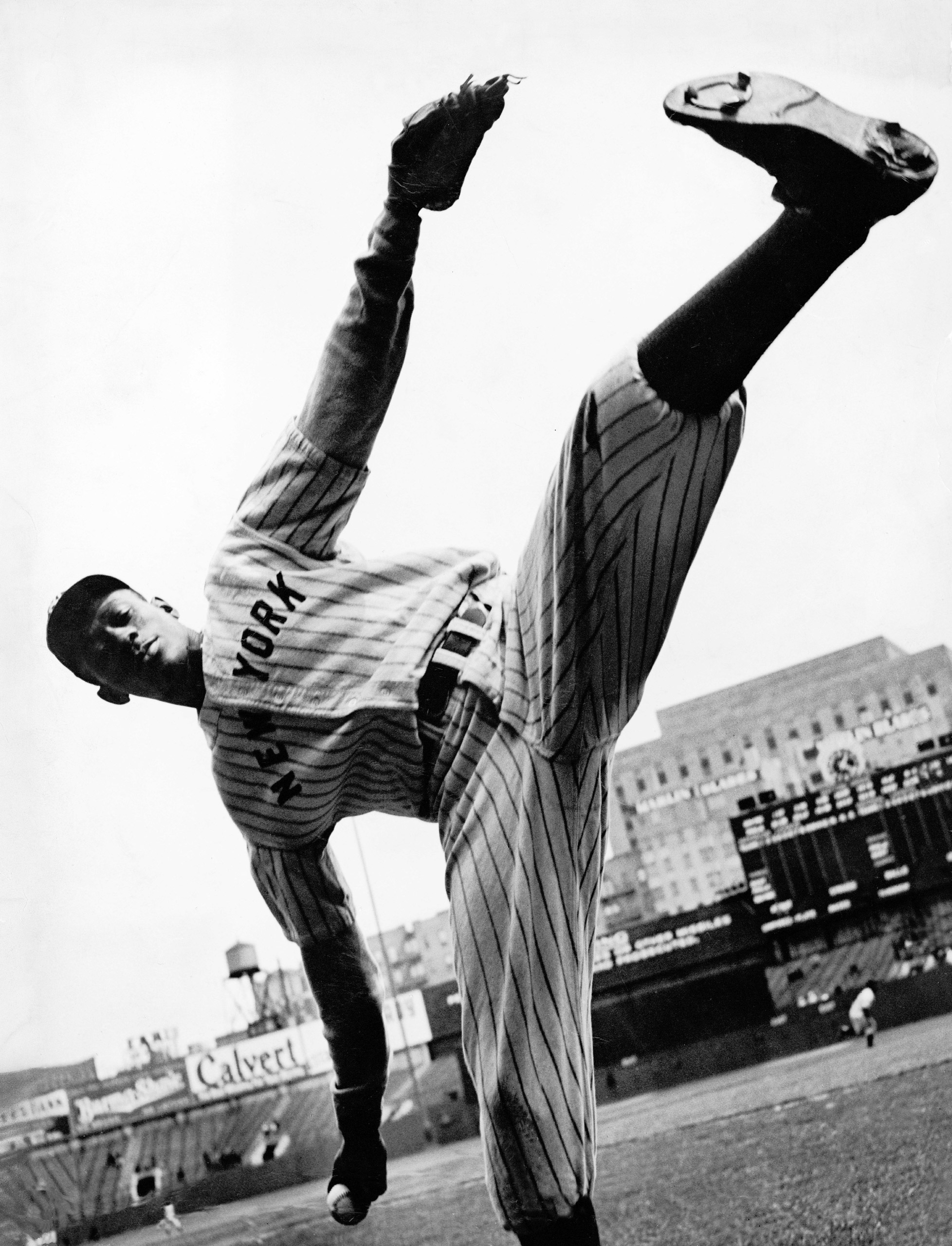

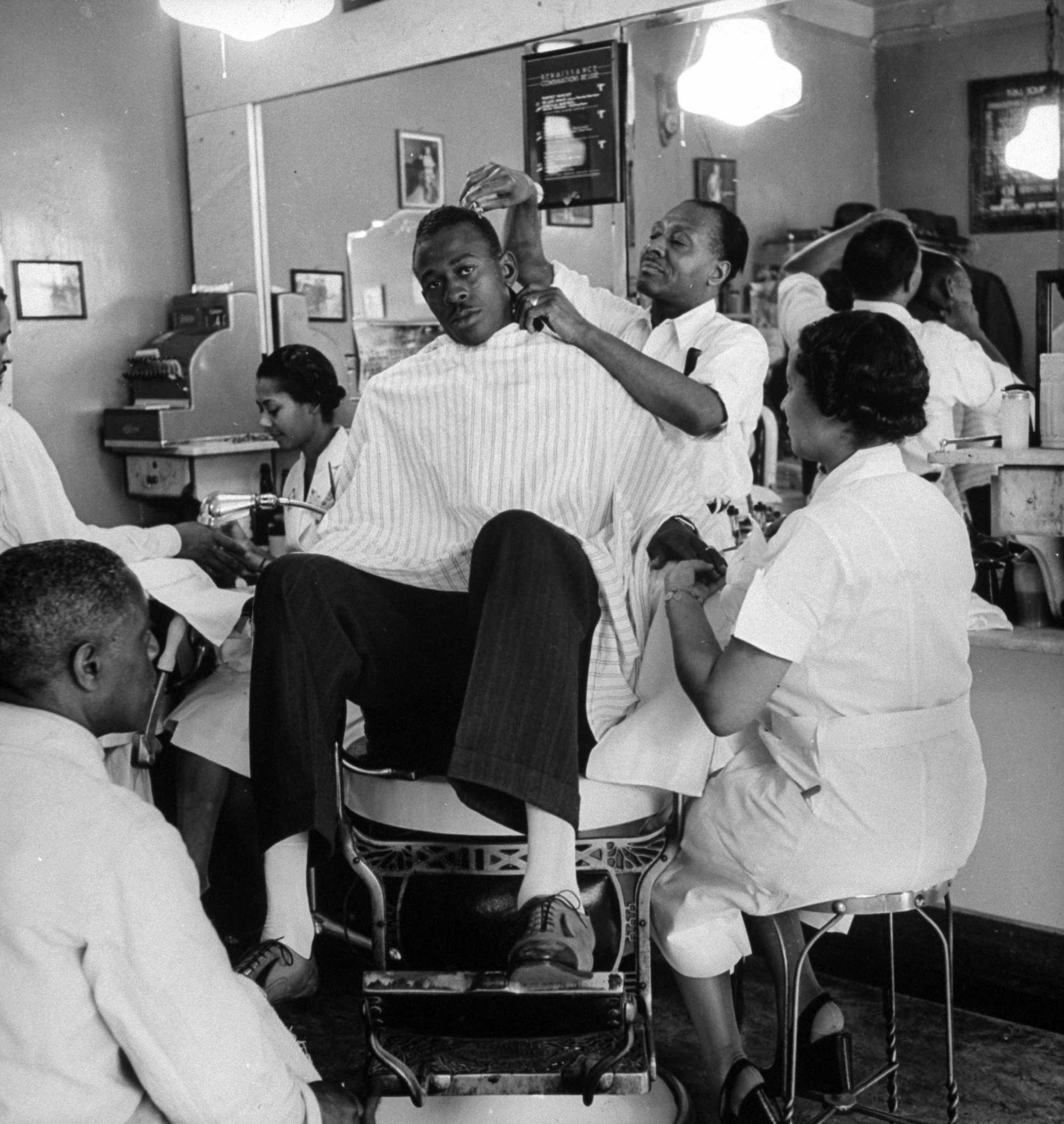

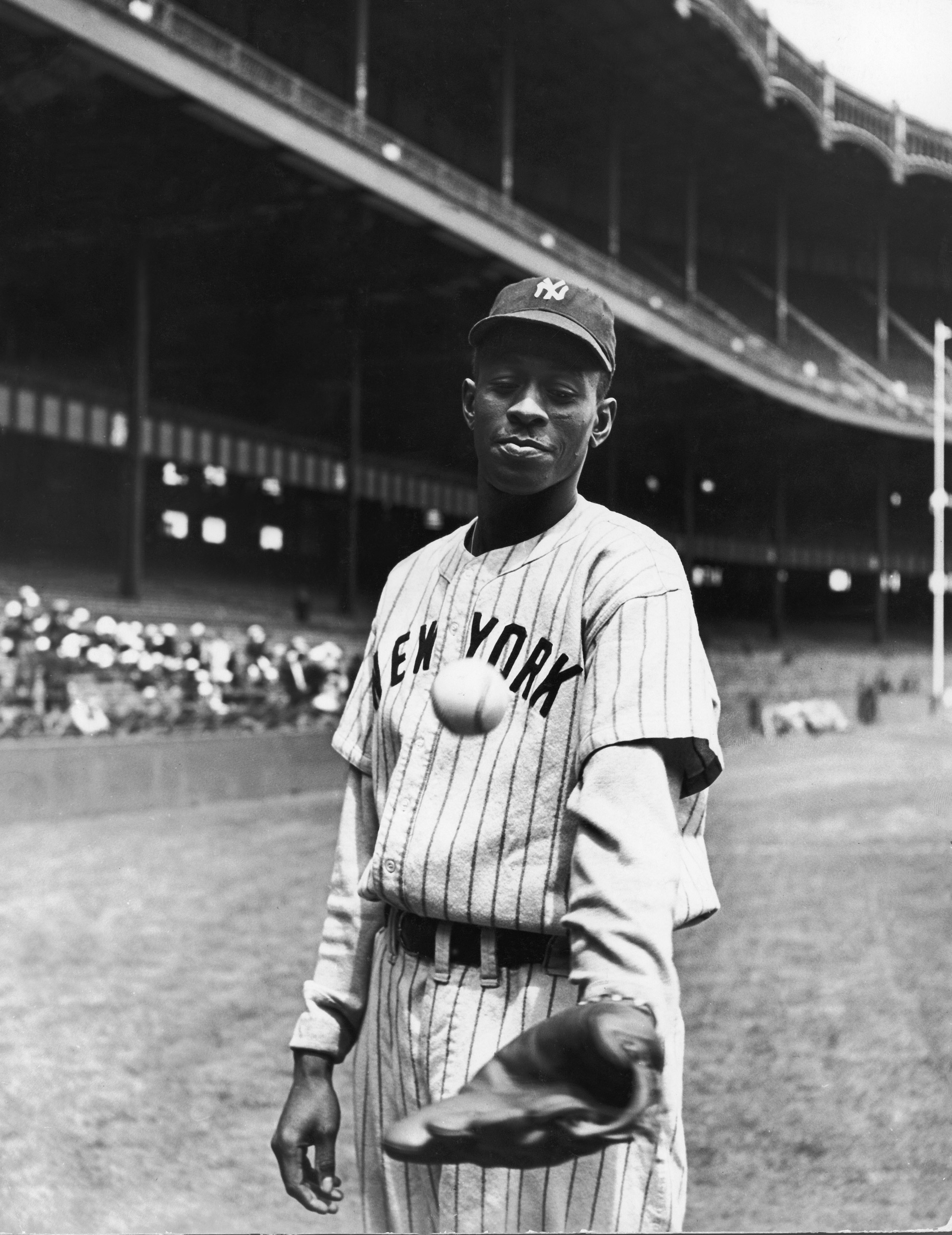

See Photos of Satchel Paige Before He Crossed the Baseball Color Line

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com