In February 2014, when Mexican marines captured the world’s most wanted gangster Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, a proud President Enrique Peña Nieto said the power of drug traffickers was being destroyed. Two previous Mexican Presidents had failed to nab Guzmán during 13 years on the run. But Peña Nieto and his Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, appeared to be better at busting these mysterious kingpins. In one interview, journalist Leon Krauze of Univision asked the President if Guzmán could ever escape from prison again as he had done back in 2001. Peña Nieto raised his hands in an incredulous gesture. “That would be more than unfortunate. It would be truly unforgivable,” Peña Nieto said. “The government will take the measures to assure that what happened years ago is not repeated.”

This Saturday, the unforgivable happened. Peña Nieto got the message as he flew to France with his Cabinet members. The 60-year-old Guzmán had fled Mexico’s highest-security prison, the Altiplano. And he had done it in spectacular fashion, going out in a tunnel that stretched 1.5 km (a mile) and had lights, air vents and a motorcycle that moved on rails. The tunnel went from a cellblock shower to a building site in a residential neighborhood, some 90 km (56 miles) from the Mexican capital.

By Sunday, the jailbreak had become a global news story, totally overshadowing Peña Nieto’s trip to France to sign trade accords. Speaking from the Mexican embassy in Paris, the President told reporters that he was ordering all forces to get Guzmán back behind bars. Soldiers searched for the kingpin from upscale Mexico City neighborhoods to the southern border with Guatemala. “This represents, without a doubt, an affront to the Mexican state,” Peña Nieto said. “But I also trust that the institutions of the Mexican state have the strength and determination to recapture this criminal.”

This latest chapter in Guzmán’s turbulent life hits the Mexican President at an already difficult time. Over the past year, Peña Nieto has been troubled by the disappearance of 43 students at the hands of cartel gunmen and corrupt police, alleged massacres by soldiers and accusations of conflicts of interest over a $7 million mansion in the name of the First Lady. His approval rating has hovered around 40%, the worst for a Mexican President in two decades. The capture of Guzmán was at least one success story. Now the kingpin has become a headache for Peña Nieto as he was for the past two Presidents.

“I was flabbergasted that there wasn’t more care of Chapo Guzmán in the prison,” says Alejandro Hope, a security analyst and former member of the federal intelligence agency. “Peña Nieto seriously underestimated Chapo. But this also shows a lot of institutional weakness. To make this escape, Chapo and his men would need plans of the prison. Where would they get those?” On Sunday, Mexican federal prosecutors took 30 prison officials in for questioning, including the director.

The jailbreak also pulls pressure from the U.S. onto Peña Nieto. Numerous U.S. courts have indicted Guzmán for trafficking cocaine, heroin, marijuana and crystal meth to American users, and the U.S. State Department put a $5 million reward on his head. Agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration tapped phones that helped the Mexican marines capture Guzmán in 2014 in a condo in the seaside resort of Mazatlán. Former DEA Administrator Peter Bensinger said he was shocked by the escape and that Guzmán “ought to have been housed in an American prison.” The U.S. had filed for the extradition of Guzmán, but Mexican judges had ruled that he should first serve time for his crimes south of the border.

Opposition Mexican politicians also used the escape as a stick to whack the President. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, an outspoken leftist who came second in the past two presidential elections, called for Peña Nieto to return immediately from France to deal with the issue. “This is a spectacular escape that will have many repercussions not only in our country but in the world,” López Obrador said in a video message. “Our country should not be a laughing stock for anybody.” López Obrador has said he aims to defeat the PRI in the next presidential election in 2018.

Hailing from a ramshackle village in the Sierra Madre mountains, Guzmán’s nickname means Shorty as he stands at 5 ft. 6 in. Despite his stature, he rose to a larger-than-life size in the drug-trafficking world, taking over the Sinaloa Cartel, the oldest and biggest network of smugglers in Mexico. He was first captured in 1993 but escaped prison in 2001, allegedly by bribing guards. On the run, he took over new turf and made it onto the Forbes billionaire list. While bringing in piles of dollars, Sinaloa Cartel gunmen also left mountains of corpses, especially in border towns such as Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez.

Despite the terror that Guzmán unleashed, some in the poor towns where he grew up see him as a kind of social bandit, bringing more with his drug money than Mexico’s businessmen or politicians offer them. Dozens of so-called drug ballads celebrate his exploits. Following his latest escape, messages on social media even called for people to go to mass in Sinaloan state capital Culiacán and give thanks to God for the gangster’s freedom. Outside the cathedral, some residents told reporters of their support for the kingpin. “I am very happy,” Maria de los Angeles Murillo told a crowd of journalists. “Because if Chapo Guzmán escapes, he will take away hunger from many people.”

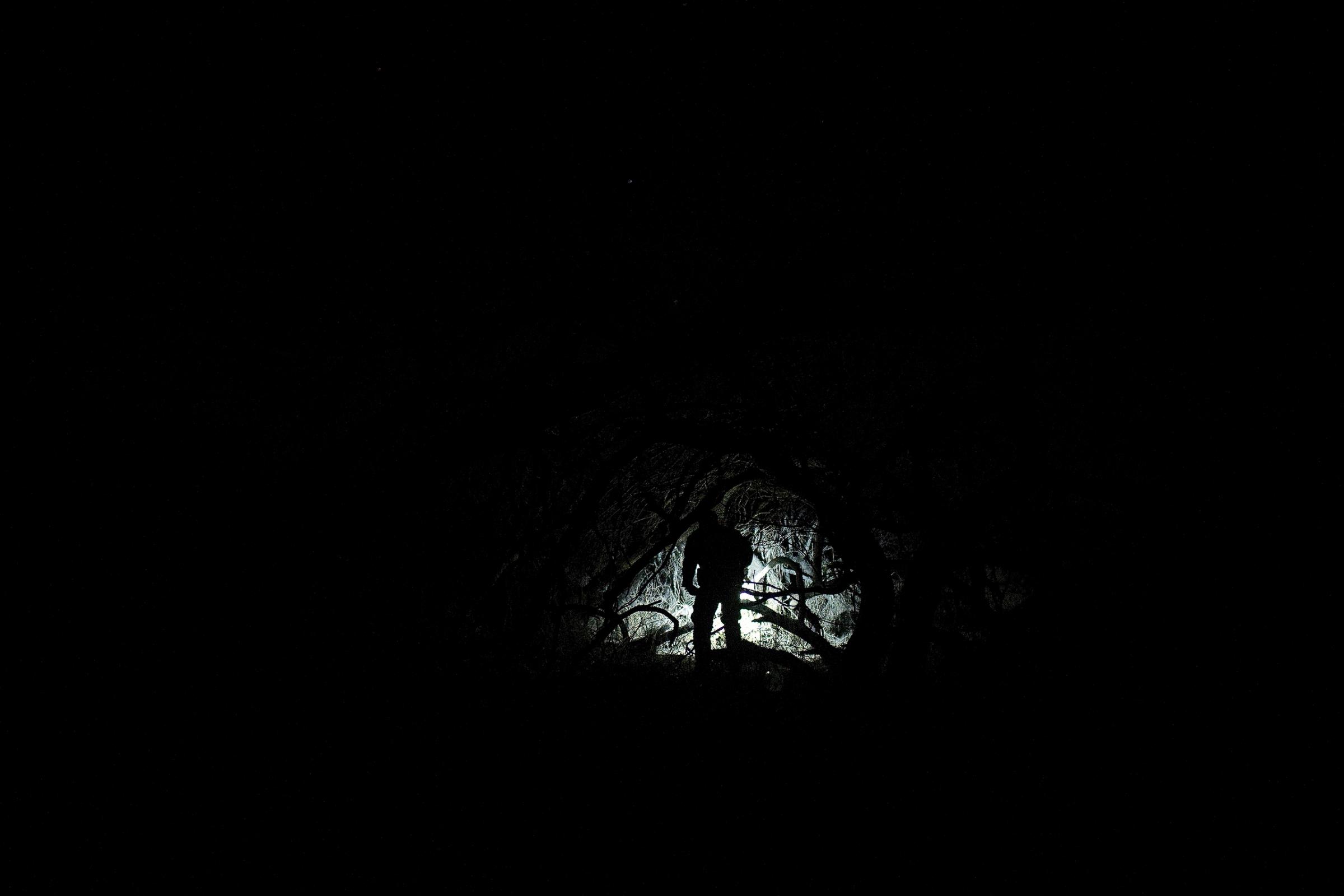

Kirsten Luce: 'The Corridor of Death': Along America's Second Border

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com