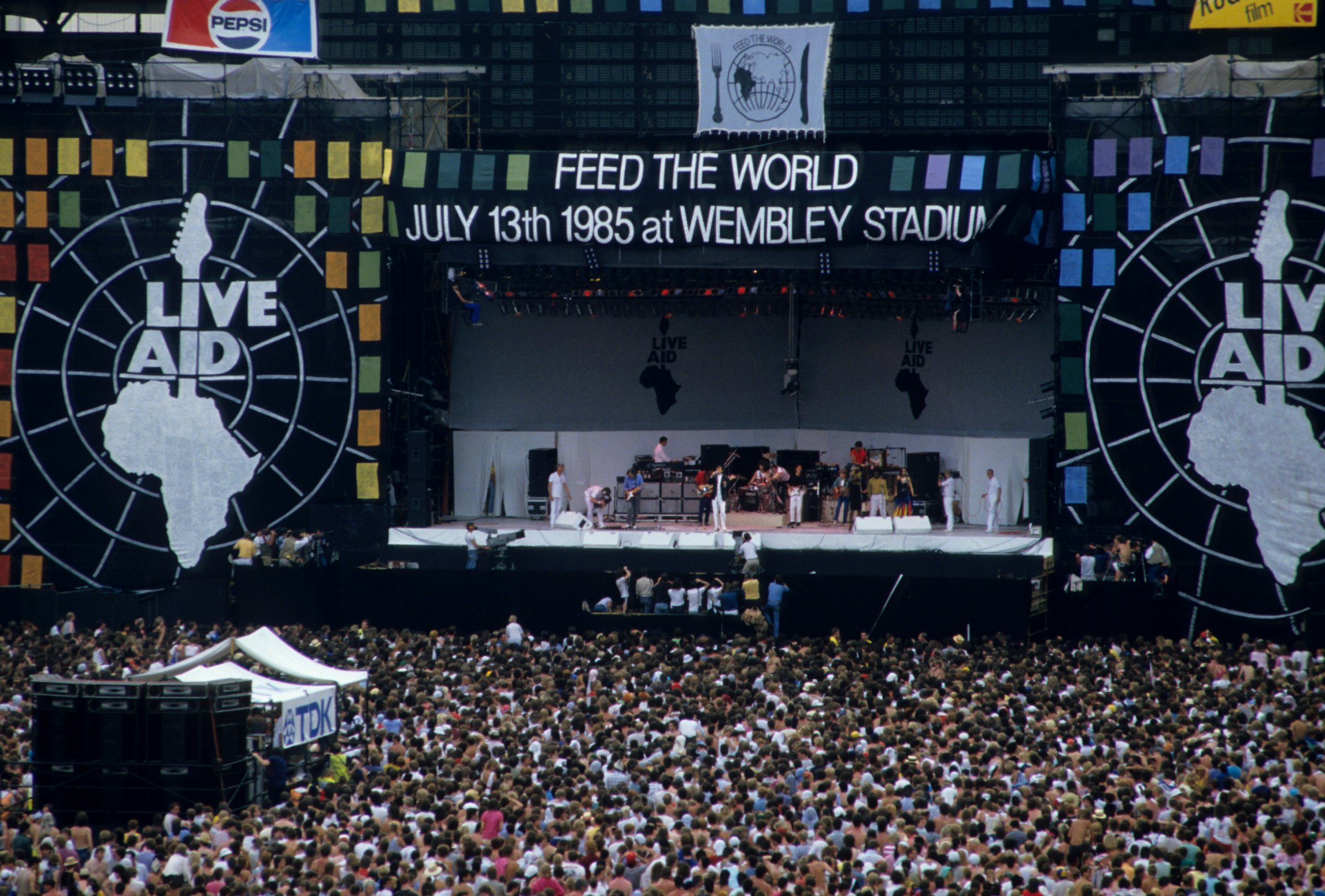

Thirty years ago today, at lunchtime in the U.K. and just before breakfast on the East Coast, 1.5 billion people sat rapt in front of their television sets, waiting for the revolution to be televised. The revolution, which was called Live Aid, was being conducted on two concert stages in London and Philadelphia and then bounced across various satellites to 150 countries, an unprecedented procedure executed with the intent of raising humanitarian aid for famine victims in Ethiopia. There had been a couple of colossal T.V. moments in the preceding 12 months — the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles; Reagan’s second inauguration — but this was to be the largest by a mile, not only that year but in the entire history of the medium.

In the contemporary cultural narrative, Live Aid was arguably the most important music happening since Woodstock. Woodstock was larger as a physical event, of course — an on-site audience of 400,000 compared with the 90,000 at Live Aid’s Philadelphia stage and the 60,000 in London — but whereas Woodstock was a gleeful veneration of the counterculture, Live Aid sought to occupy the mainstream psyche with a traditionally uncool message: one of humanitarian awareness and sympathy. It worked damned hard to do it too. Bob Geldof, the musician turned inadvertent activist who found himself at the helm of the event, envisioned a show “as huge as humanly possible,” one that defied all precedent to bring music to the world, and in turn aid for Africa.

And so for 16 hours on July 13, 1985, the biggest names in rock-‘n’-roll took to the stages of Wembley and John F. Kennedy Stadiums, by all accounts playing their hearts out. In London, Queen delivered what many consider to be the band’s finest performance. Two years before The Joshua Tree confirmed U2’s position at the vanguard of superstardom, Wembley Stadium stood rapt as the group delivered a twinkling rendition of the now-mostly-forgotten “Bad,” with a mulleted, wholly unpretentious Bono leaping from the stage to dance with a young woman in the front row. When Elvis Costello covered The Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love,” the stadium joined in.

“The audience was at the center of it — they were the stars of the show. The acts who succeeded that day were the acts who realized that,” David Hepworth, the British music journalist who co-presented the BBC’s Live Aid coverage, told TIME. “That’s what Live Aid changed in the music business — afterwards, you had this explosion in scale, the rise of these massive, often outdoor concerts.”

It wasn’t perfect, of course. When Paul McCartney played “Let It Be,” the microphone on his piano failed for the first two minutes of the song (not that it mattered much—in one of the most moving moments of the entire broadcast, the audience sang along anyway). In Philadelphia, Bob Dylan allegedly infuriated Geldof when he suggested onstage that some of the day’s proceeds go toward struggling American farmers. A number of journalists raised their eyebrows at the scale of the event. TIME’s coverage was decidedly ambivalent, noting Live Aid’s success as a charity benefit but seeming nonplussed about the larger idea of it.

“Television may be great for raising big bucks, but it is no friend of live music, especially not of rock ‘n’ roll, which needs urgency, immediacy, volume and balance,” TIME’s critic Jay Cocks wrote. “If this occurred to Bob Geldof … it obviously did not give him serious pause. He meant to raise money, and the tunes could match up to the ideal or not. Music was the come-on of the day, not the essence, and world television was like a vast electronic banking window.”

Other critics were — and still are — harsher, deriding the concert as a failed exercise in misguided imperialist sympathy. The more than $150 million it raised, they said, did next to nothing to relieve the suffering in western Africa, and maybe even worsened the political situation there.

But those who condemn Live Aid in relation to the Ethiopian famine may be failing to comprehend the legacy of the event, which transcends the practical realities of one sole political cause. Decades before the first online sympathy story went viral, Live Aid demonstrated that compassion could be commodified in the interest of the greater good. In an era commonly remembered as one of egotistical greed and unfeeling indifference, a third of the world’s population turned to their television sets to watch an exercise in empathy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com