The Fuller Project for International Reporting reports on women in foreign affairs and women's rights.

Almost 27 million viewers in the U.S. watched the country defeat Japan in a stunning 5-2 victory during the FIFA Women’s World Cup Final Sunday. This was the largest U.S. audience ever to watch a soccer match—a testament to the growing popularity and global power of women’s sports teams. Yet as we watched with our young daughters the game from Turkey, where girls soccer teams are scant and female players face discrimination and harassment, our enthusiasm was tempered by a stark reality: For many of the world’s women, playing soccer is a distant dream.

Across the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and Asia, millions of women face legal, cultural, and religious barriers that forbid them from entering the pitch. Even in countries where there are no formal restrictions, women often face death threats, accusations of unfeminine behavior, and heckling and catcalling from strangers on the sidelines. In some countries, women are even forbidden from entering soccer stadiums just to watch.

Can we really celebrate American women as world champs with such an uneven playing field?

In Middle Eastern countries including Yemen, Oman, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, nascent women’s national teams confront religious challenges to their participation. Clerics in Saudi Arabia have said that female sports constitute “steps of the devil” toward immortality. Egyptian women report that family members are often the ones to keep girls off the field, telling them that soccer is haram, forbidden in Islam. Afghan women players have received threatening text messages. Indian women were recently forced off the field after a Muslim cleric issued a fatwa against men watching girls play in skirts.

In some African countries, women are effectively kept off the field by the lack of sports bras and sanitary napkins, as well as financial unwillingness to support them. Ugandan women’s under-20 soccer team, for example, never even made it to the World Cup—their government pulled them from competing at the last hour, citing lack of funds.

When women athletes do make it onto the field, they often confront an onslaught of opinions on how they should—or shouldn’t—dress. In countries with hot temperatures, players are often forced to cover up their wrists and legs. In Iran, Singapore, France and elsewhere, women wearing the hijab are not allowed to play. FIFA has played a major part in this unfairness—until 2012, the organization banned headscarves.

In South America, the pressure can go the other way. In Brazil, where only about 1% of soccer players are women, team owners have tried to sexualize female footballers, issuing skimpy uniforms as a tactic to attract crowds. In what is known as one of the world’s most soccer-loving nations, the law kept women out of soccer until 1979 because it was “incompatible with female nature.”

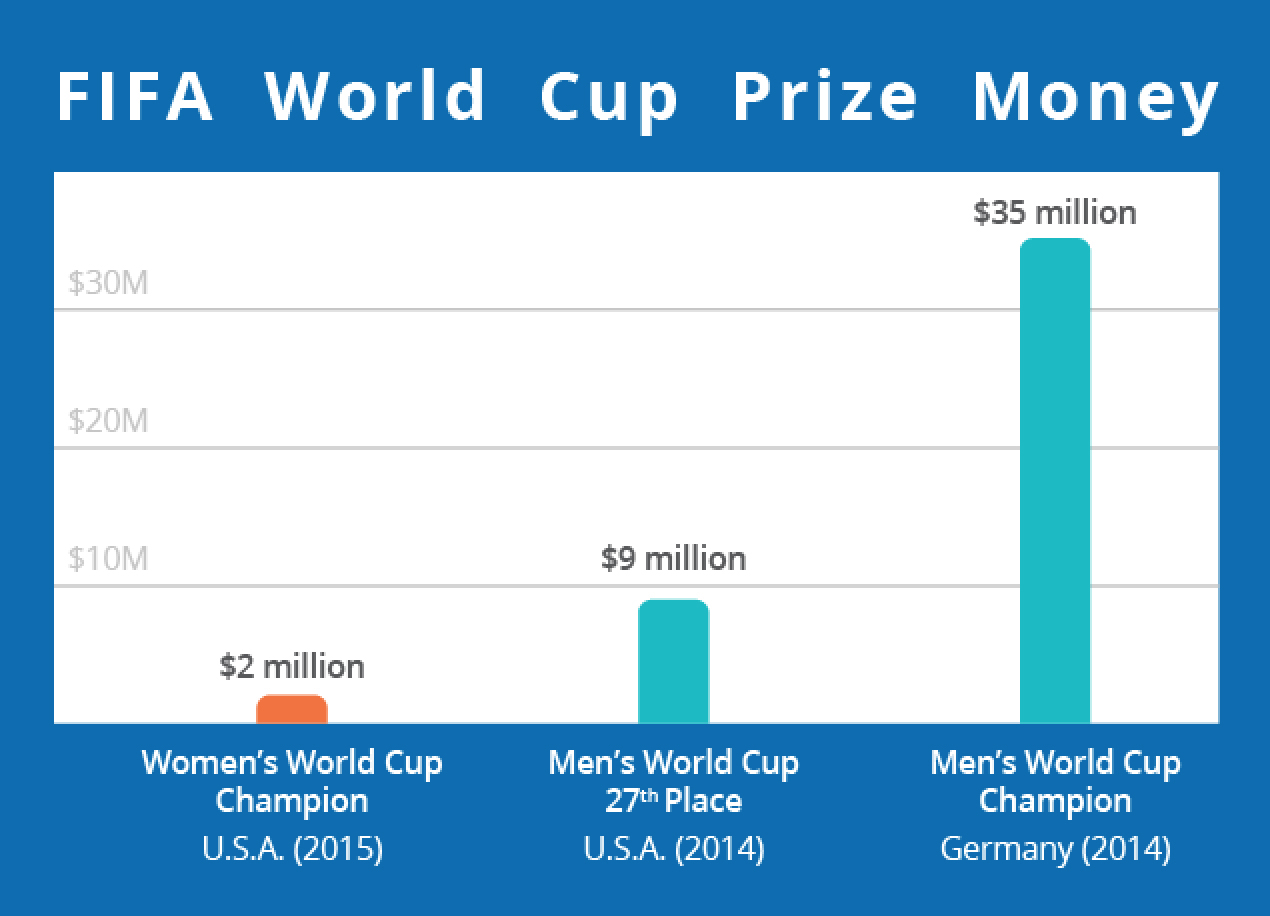

Funding also factors into these unfair practices, with many U.S. women players earning about 99% less than men. Some women soccer pros are paid at levels below the poverty line. The men’s World Cup last year paid out $576 million—nearly 40 times the predicted amount for the women’s World Cup. This year, the U.S. women’s team will receive a total prize of $2 million for winning the World Cup, less than a fourth of what the men’s team received for placing 27th.

Sexism around women’s soccer exists in Western countries, too, where women’s soccer has only recently been embraced. A 1921 Football Association edict in the U.K. banned women’s football for 50 years. More recently, lingering sexism reared its head again last week after the association tweeted that the women’s team, which placed third in the World Cup, would go back to “being mothers, partners and daughters” upon their return.

Last year, a group of women including U.S. Women’s National Team player Heather O’Reilly, unsuccessfully sued FIFA over the artificial turf that they were forced to play on. Reilly told NPR that men refuse to play on fake grass, and that the decision was a “blatant demonstration of FIFA not placing the women side by side with men.”

Much has been made of soccer as the great global equalizer, “a common language, a shared culture … an affirmation of identity,” according to Tom Watt, author of A Beautiful Game. With a patch of dirt and a ball, young boys from the shantytowns of Brazil or the ghettos of Morocco can become world famous players like Diego Maradona, Zinedine Zidane and David Beckham. Soccer has an almost myth-making ability to transcend identity and unite the world.

Why let gender be the remaining barrier?

Despite restrictions, more women around the world are taking to the field—and that’s good not just for women but for everyone. In a sport that the U.S. has struggled to dominate globally, women are making the country proud. Soccer can also play a role in reducing obesity and smoking, encouraging teamwork, and increasing confidence.

The U.S. women’s soccer team captured the world’s attention—now they should use their stage to demand that all governments support women in soccer.

FIFA can be an ally in this—the organization just issued a report on women in soccer, pointing to the urgent need for funding, benefits of increasing the number of licensed players and competitions, and the need to boost the number of female coaches—now only 7% in women’s soccer. We know equalizing funding works: Title IX is credited with ushering in a new generation of female athletes, and women make up more than 40% of all soccer players in the U.S.

U.S. World Cup champion Briana Scurry recently wrote for TIME about how David Letterman called the 1999 U.S. women’s team “babe city.” A lot has changed since then, she said. “We showed the world that women could be powerful, strong, determined, and capable of guiding their own destinies, too. Now women players are more appreciated for their achievements on the field and not for how they look.”

Imagine how much more exciting the games would be if every woman around the world could play.

Xanthe Ackerman and Christina Asquith are journalists with The Fuller Project for International Reporting. Fuller Project research fellows Zarifah Mohamed Zein and Ilina Talwar contributed to the reporting. Join the discussion: #LetGirlsLearn.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com