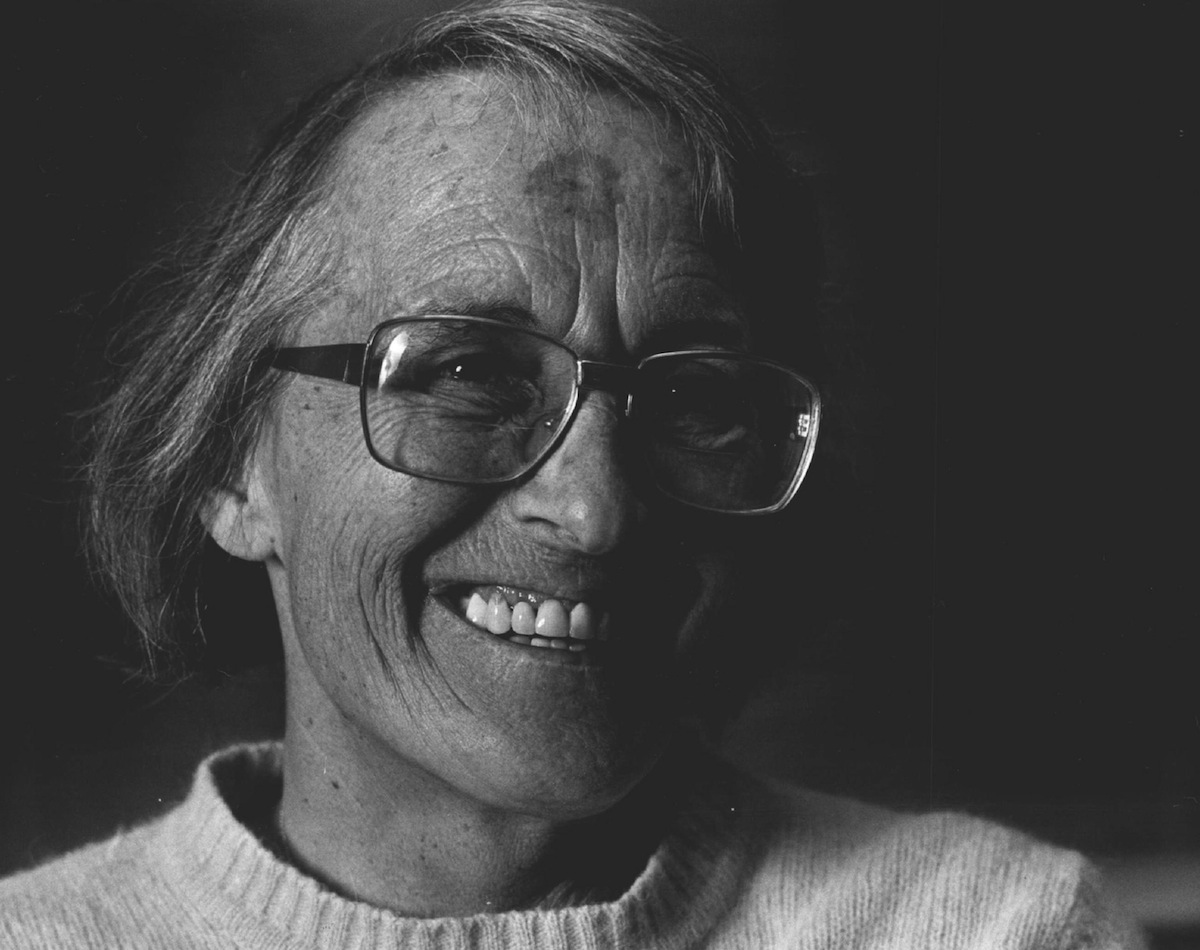

The idea that the dying might have something to teach the living seems self-evident. After all, as the psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross put it, in a 1969 profile in LIFE Magazine, who better to offer instruction on “the ultimate human crisis” than those in the midst of it?

“When I wanted to know what it was like to be schizophrenic,” Dr. Kübler-Ross told TIME earlier the same year, “I spent a lot of time with schizophrenics. Why not do the same thing? We will sit together with dying patients and ask them to be our teachers.”

And yet the medical community reacted as though she’d suggested interviewing ghosts about the afterlife (which, to some degree, she later did). The institutional hush surrounding terminal illness was so deeply rooted by the 1960s that Kübler-Ross’s suggestion came as a shocking breach of protocol.

“The reaction of physicians ranged from annoyance to overt hostility,” TIME attested.

Kübler-Ross, born in Switzerland on this day, July 8, in 1926, was not deterred. Her seminar at the University of Chicago’s Billings Hospital, begun in 1965, featured terminally ill patients as lecturers—and helped lift the taboo on frank discussions of death in hospitals across the country. In her bestselling 1969 book, On Death and Dying, she compiled the insights she gleaned from these patients, most notably her conclusion that they typically struggled through five stages at the end of life: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

While other researchers have questioned whether the five-stage model accurately depicts the experience of dying (or grieving in general), few deny that Kübler-Ross’s work led to improvements in the way terminally ill patients were treated. As she revealed, they didn’t necessarily appreciate being ignored in hospitals or tiptoed around by relatives and friends.

TIME summarized Kübler-Ross’s conclusion that “…the patient who is not officially told that his illness is fatal always discovers the truth anyway, and may resent the deception, however well meant.” The story goes on:

The dying are living too, bitter at being prematurely consigned—by indifference, false cheerfulness and isolation—to the bourn of the dead. It is not death they fear, but dying, a process almost as painful to see as to endure, and one on which society—and even medicine—so readily turns its back.

Kübler-Ross’s seminars lifted terminally ill patients out of their isolation, at least for a time, and gave them a platform to share their fears and their hopes. (Even those who made it to the acceptance stage rarely gave up hope, according to TIME.)

Just as importantly, the seminars gave Kübler-Ross’s students a glimpse into the part of life that remains one of our culture’s best-kept secrets. As LIFE concluded in 1969, “It is very much as if, while watching the others come to an understanding with death, they begin to move toward understandings of their own.”

Read more from 1969, here in the TIME archives: Dying: Out of Darkness

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com