“Someday the mountain might get ’em / But the law never will.” –Waylon Jennings

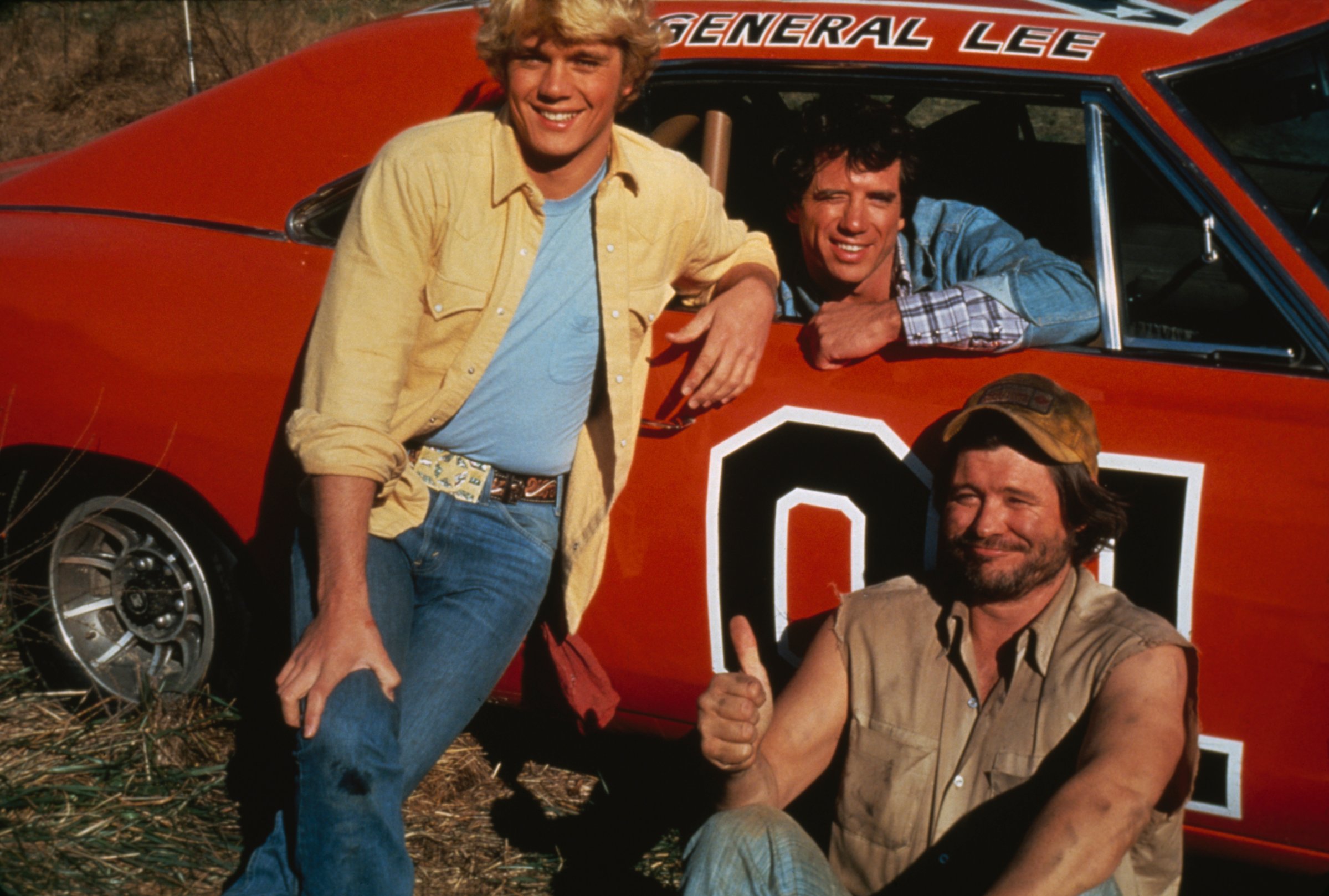

In the end, it was neither the law nor the mountain that got them Duke Boys. It was TV Land, which pulled reruns of The Dukes of Hazzard–whose muscle car the General Lee was emblazoned with the Confederate flag–amid the controversy after the racist massacre in Charleston whose perpetrator had posed with the banner. (The network hasn’t given a reason, but the timing is tough to overlook.) The move prompted an outraged reaction from costar John Schneider: “The Dukes of Hazzard was and is no more a show seated in racism than Breaking Bad was a show seated in reality.”

From many other folks, I expect, the reaction was more like: “Someone was rerunning The Dukes of Hazzard“? If you grew up with the show as I did, your memories probably mostly involve jean shorts, cars jumping over ponds and “Enos, you dipstick!” Was there really anything else to it?

The show’s no longer on TV Land, but you can watch the pilot free on Amazon (where subsequent episodes are $1.99 a pop). So I did.

It is still as gloriously shiny and empty as a collectors’ metal lunchbox, a Southern-fried cartoon (which later became an actual cartoon) jacked up with ’70s T&A. The plot involves the Dukes hijacking a shipment of illicit slot machines from Sheriff Roscoe P. Coltrane in order to save an orphanage; there’s a climatic prison escape involving a blow-up doll. The dialogue includes Luke’s immortal line, “Bo, you drive like my Aunt Fanny whips apple butter!” (Sidebar: They’re cousins. Isn’t it our Aunt Fanny?) There are some notable performances–Sorrell Booke’s gluttinously avaricious Boss Hogg, especially, is like Big Daddy filtered through John Waters–but the sensibility is more Tennessee Ernie Ford than Tennessee Williams.

But Dukes is also a fascinating document of its time in history–both TV and American. Dukes premiered in 1979, at the height of jiggle TV (Three’s Company, Charlie’s Angels) and the Carter-era pop fascination with Southern good-ole-boy stories (Convoy, Smokey and the Bandit). It was still firmly the post-Watergate era, in which the suspicion of The Man became mainstream, and some of the most popular screen heroes were charming rogues whose broke laws enforced by corrupt authorities (Han Solo, say, or many of Burt Reynolds’ ’70s roles). But the Reagan revolution, and its embrace of America’s past, was just a year away.

So the first messages you get from Waylon Jennings’ theme song are also the most essential: Bo and Luke were “good ol’ boys” but they were also “fightin’ the system.” They were traditionalists, but they were also rebels. The Duke boys weren’t political, but they were at least small-c conservative–they stood for old ways and ancient traditions.

And the show came along at a time when conservatism was figuring out a different way to present itself, not as the establishment but as the underdogs, the outsiders–essentially repurposing the hippie ideas of the people vs. the power into the little folks vs. the big government. (First Blood, which came out a few years later, cast Reagan-era icon Rambo as a solder betrayed by the powers-that-be–including, like the Duke Boys, a venal Southern sheriff.) Even the little things, like the Dukes’ bow-hunting, are about anti-government individualism: poor folks need food, and “Jesse don’t take kindly to no government assistance. He’d rather starve.”

This isn’t William F. Buckley’s elitist conservatism, standing athwart history and yelling “Stop!” It’s leaning out the window of a Dodge Charger and yelling “YEEEEHAWWWW!”

So about that rebel flag. The Dukes pilot doesn’t talk about it directly, but it does allude to the Civil War, in a scene that explains why Uncle Jesse (Denver Pyle) gave up the 200-year-old family moonshine business to save his nephews from jail: “They fought everybody from the British to the Confederacy to the U.S. government to stay in it.” On the one hand, the Duke boys’ car is the General Lee; on the other hand, their ultimate enemy–Jefferson Davis Hogg–is named for the president of the CSA.

There’s nothing about slavery or states’ rights in there, but the mythmaking is familiar enough. The Dukes fly the Confederate flag, the setup assures us, but they’re outside any negative ideas you have about the Confederacy. They’re just little guys going up against a succession of big guys. Just’a good old boys! There’s nothing overt there about the flag–and the series didn’t dwell on it after that–but it’s very much part of the “history not hate” message that led, by now, to a majority of American whites seeing the flag as a symbol of pride while most black Americans see it as one of racism, according to a CNN poll.

Of course, Ben Jones–the former Georgia congressman who played the Dukes’ coconspirator Cooter and now owns a chain of Hazzard-themed museums–recently insisted, “in Hazzard County there was never any racism.” More accurately, there just wasn’t much race. The black characters in the pilot are limited to a construction worker with no lines in the first chase scene, and a small part for the Dukes’ friend Brodie–played by Champ Laidler, credited with two episodes in total. (Later, there would be a minor recurring role for the African American sheriff of a neighboring county.)

That’s not to say The Dukes of Hazzard was some kind of diabolical historical whitewash so much as it was a network TV series in 1979, trying to pull in viewers nationwide for a story about the South without touching anything that inflamed people a decade or a century before.

So Northerners get a funny story of backwoods tricks played on backwoods hicks, loaded up with getaway music and casual stereotypes. (“If you weren’t my cousin, I’d marry you,” Bo tells Daisy in the pilot. “When did that ever stop anyone in this family before?” she asks him.) Southerners get a populist version of pride and rebellion without baggage. The kids get car chases with CB radios. The grown-ups get Daisy on a roadside in a bikini and/or Bo and Luke with their shirts unbuttoned to the waist. (There are more ’70s hormones floating around Hazzard County than during happy hour at the Regal Beagle.)

It may be right to say that no one ever tried to write politics into The Dukes of Hazzard, racial or otherwise. (Though there was a lot more politics in the pilot than I would have thought: there’s an election going on for Sheriff, and Coltrane went crooked when he lost his pension after a local bond initiative got voted down.) But that doesn’t mean it isn’t about them all the same. You can’t feature the flag of Dixie and not be about the South and race, like it or not, even if only by passively feeding into the argument that the flag is only about family pride, good ol’ boys and good ol’ times.

Does that mean the show should have been pulled off the air? I am a white man from the North: there may be no opinion on the Confederate flag less relevant than mine. But as someone who believes that pop-culture history is important history all the same, I agree with the Washington Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg, who argued for reading and watching Gone with the Wind despite and because of its race problems, as “a valuable document of the way the Lost Cause curdled into a regional religion.” The Dukes of Hazzard–like any TV in our past–is part of us, whether we watch it or not.

But you’re also not a killjoy if you watch it, get a kick out of it–and yet are weirded out by the awesome stunt car flying the flag of slavery. The Duke boys, like Waylon told us, wouldn’t change if they could. But the times, they change anyway.

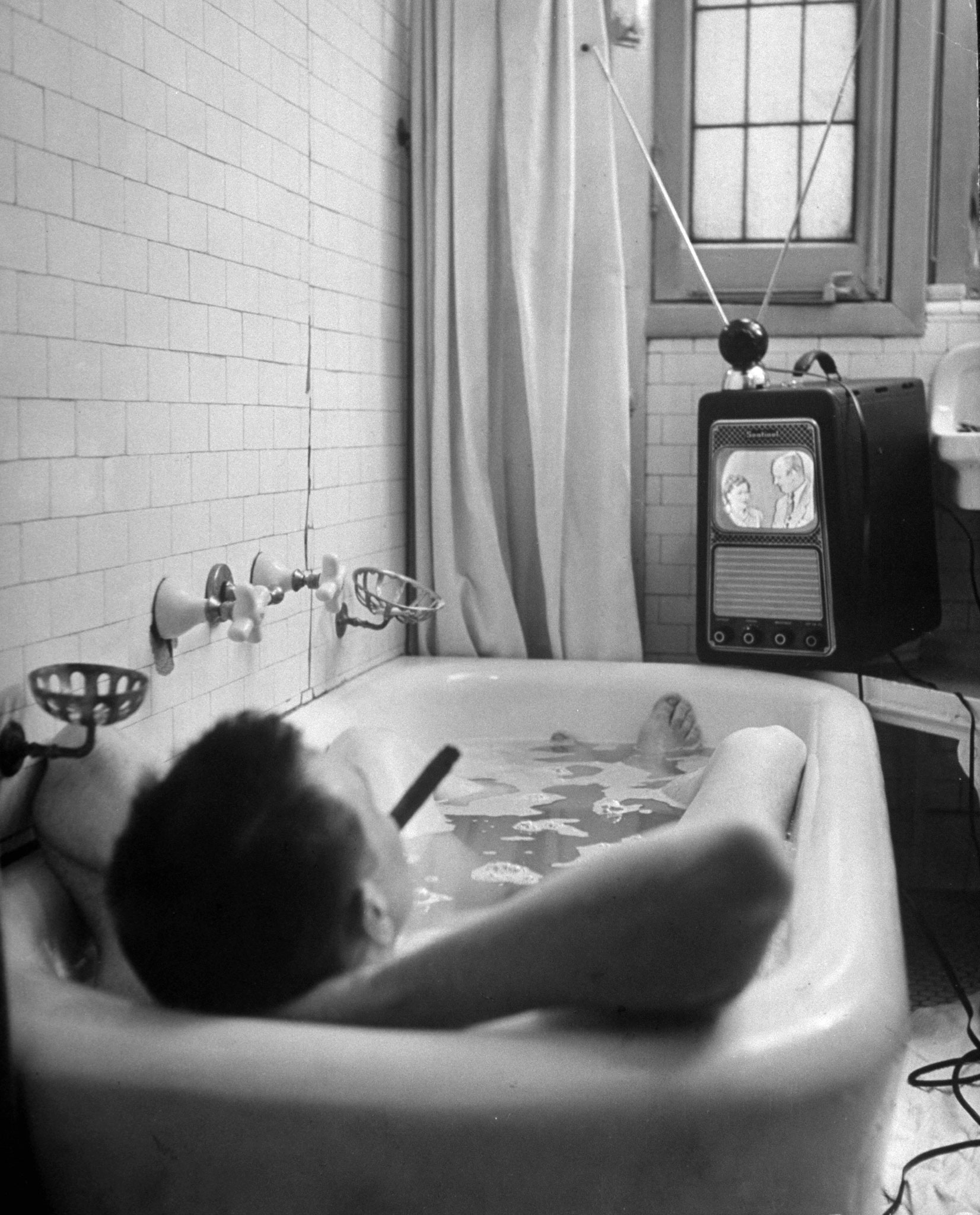

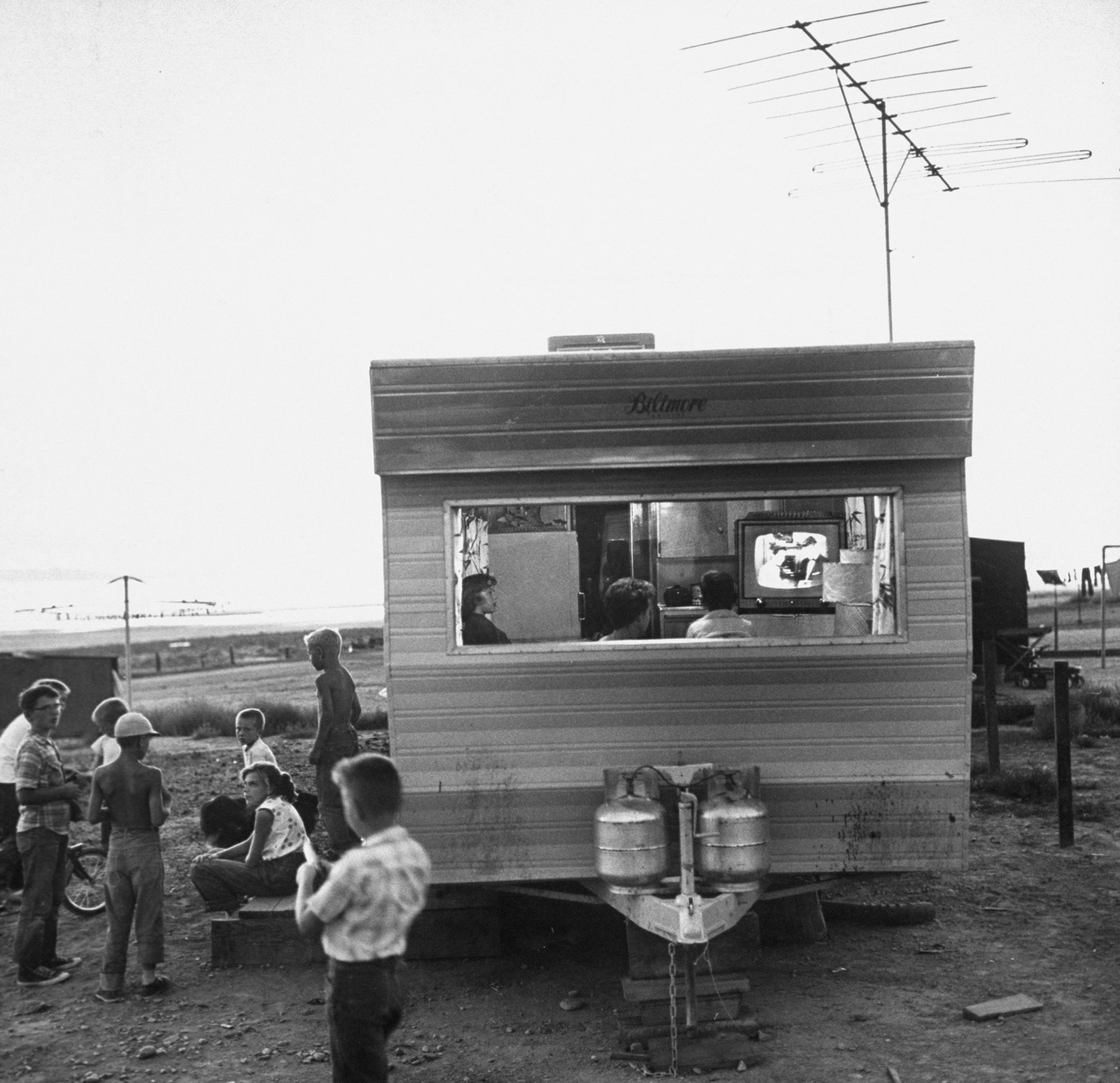

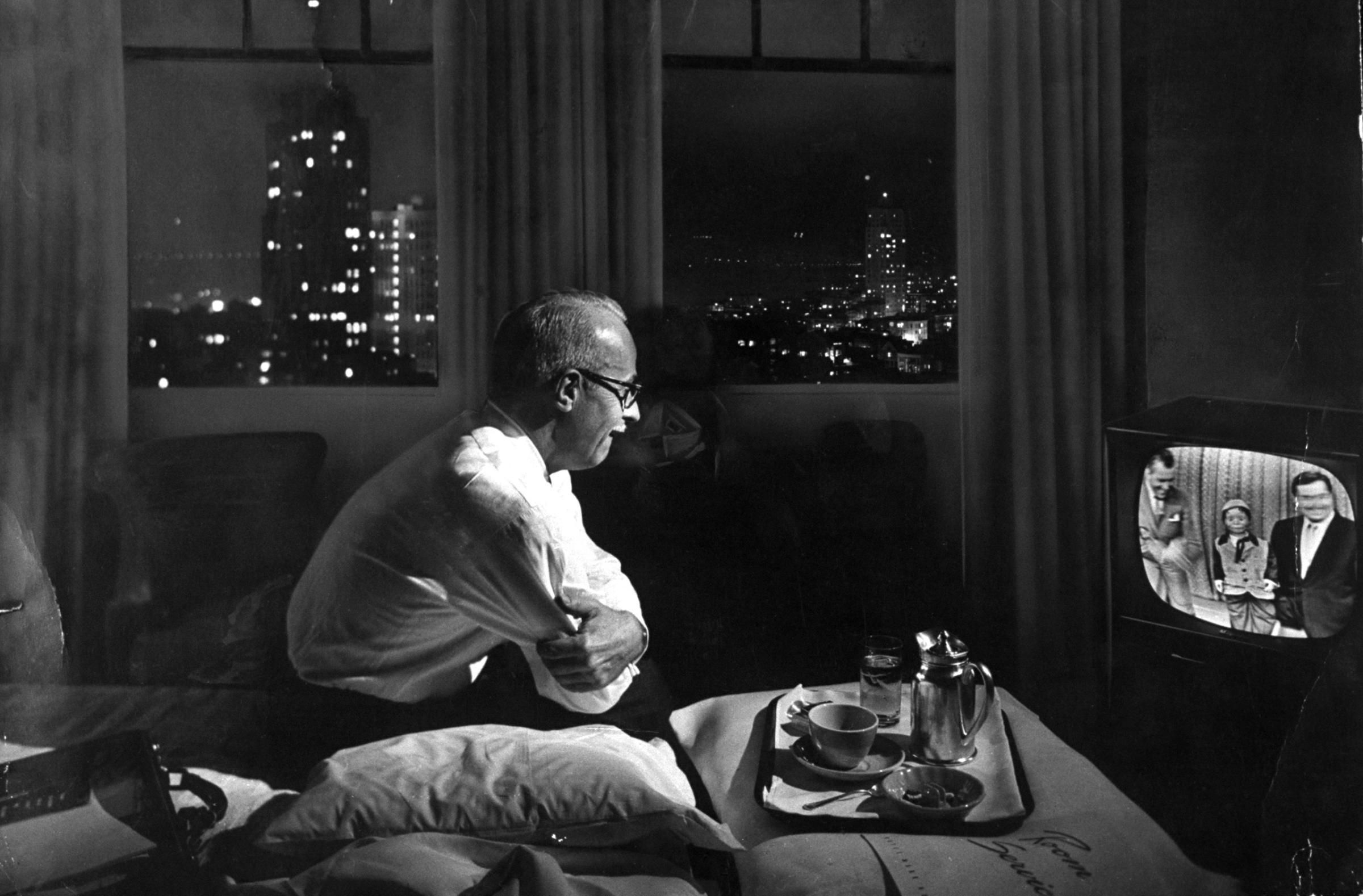

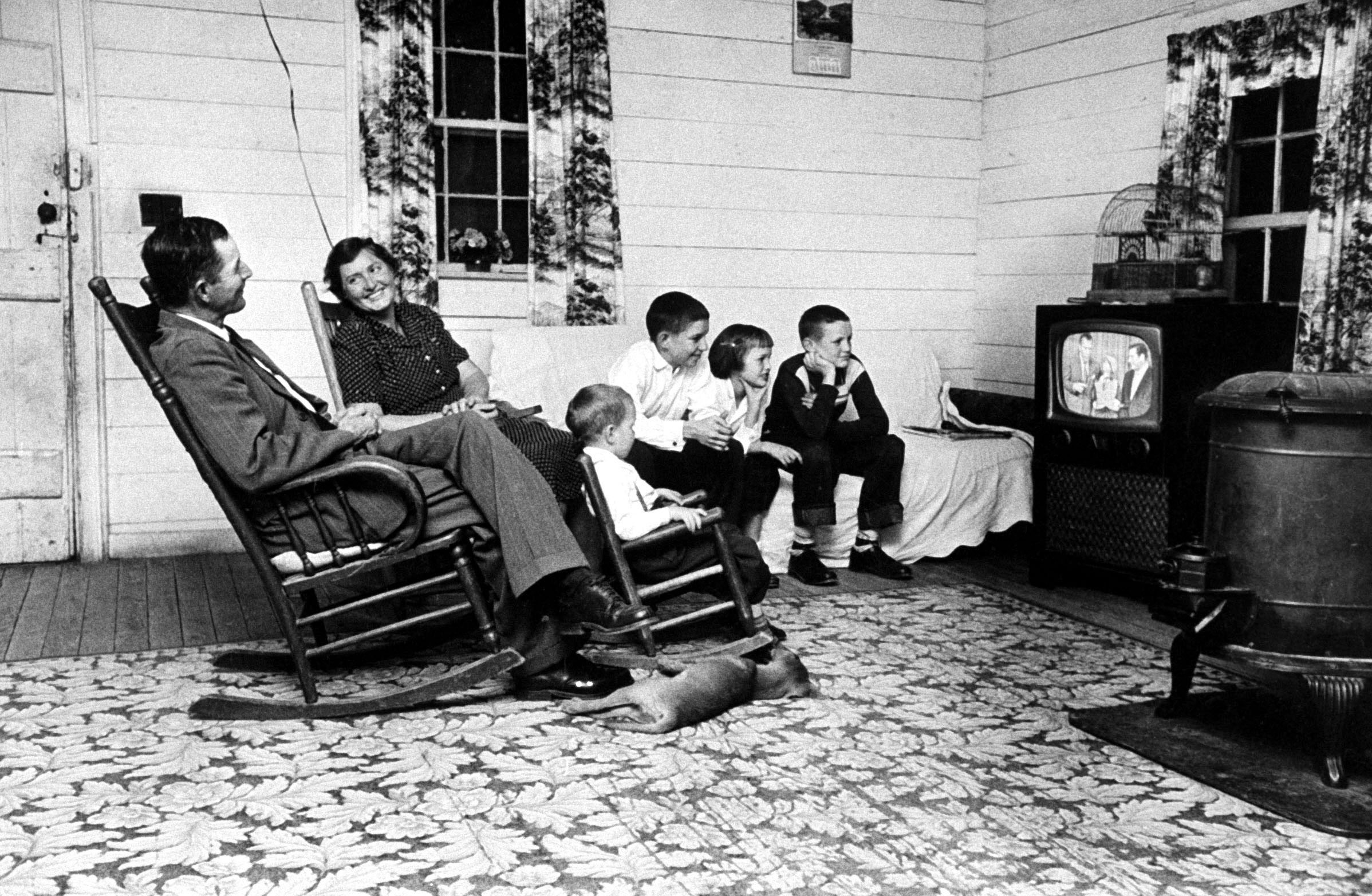

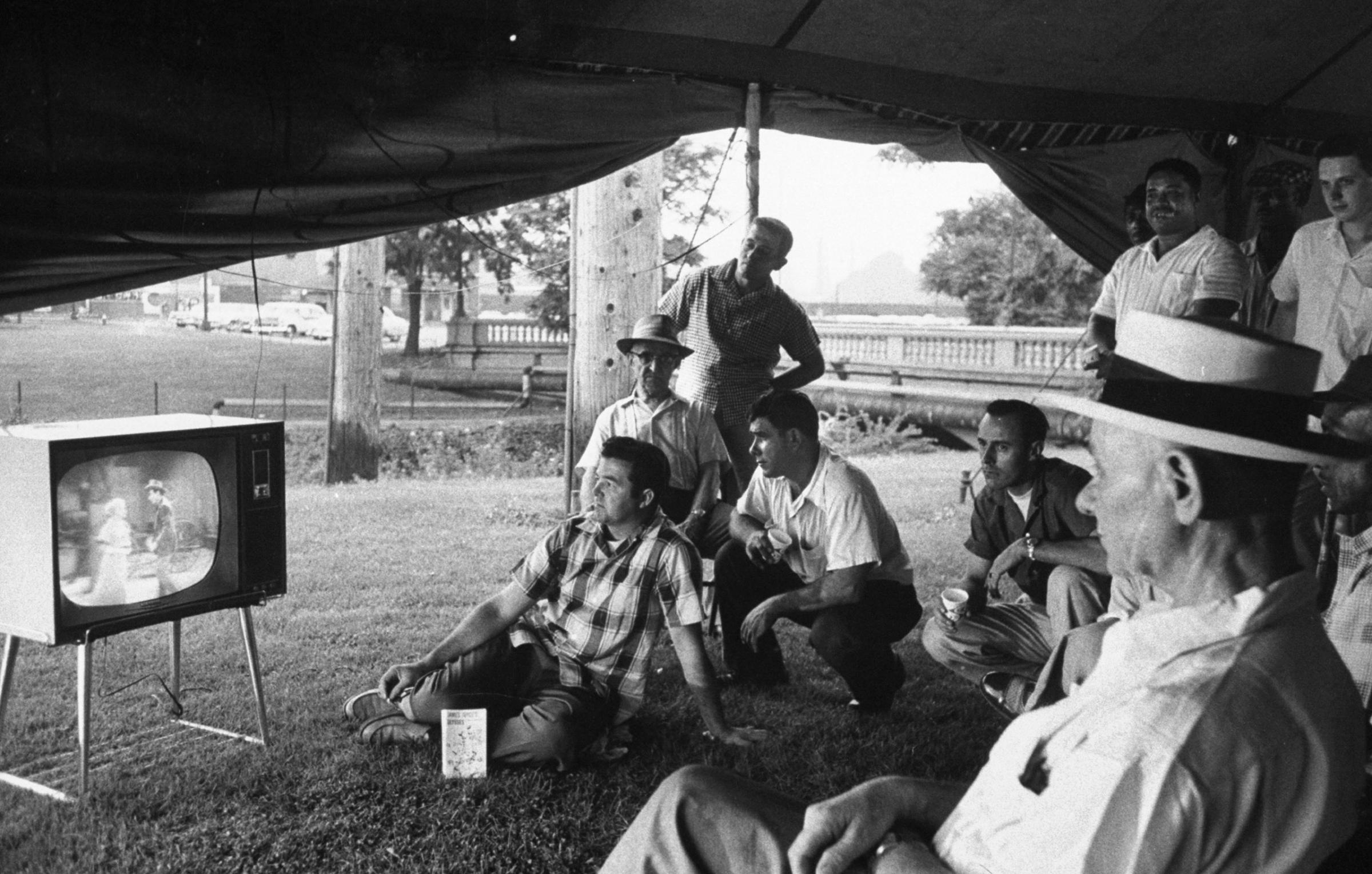

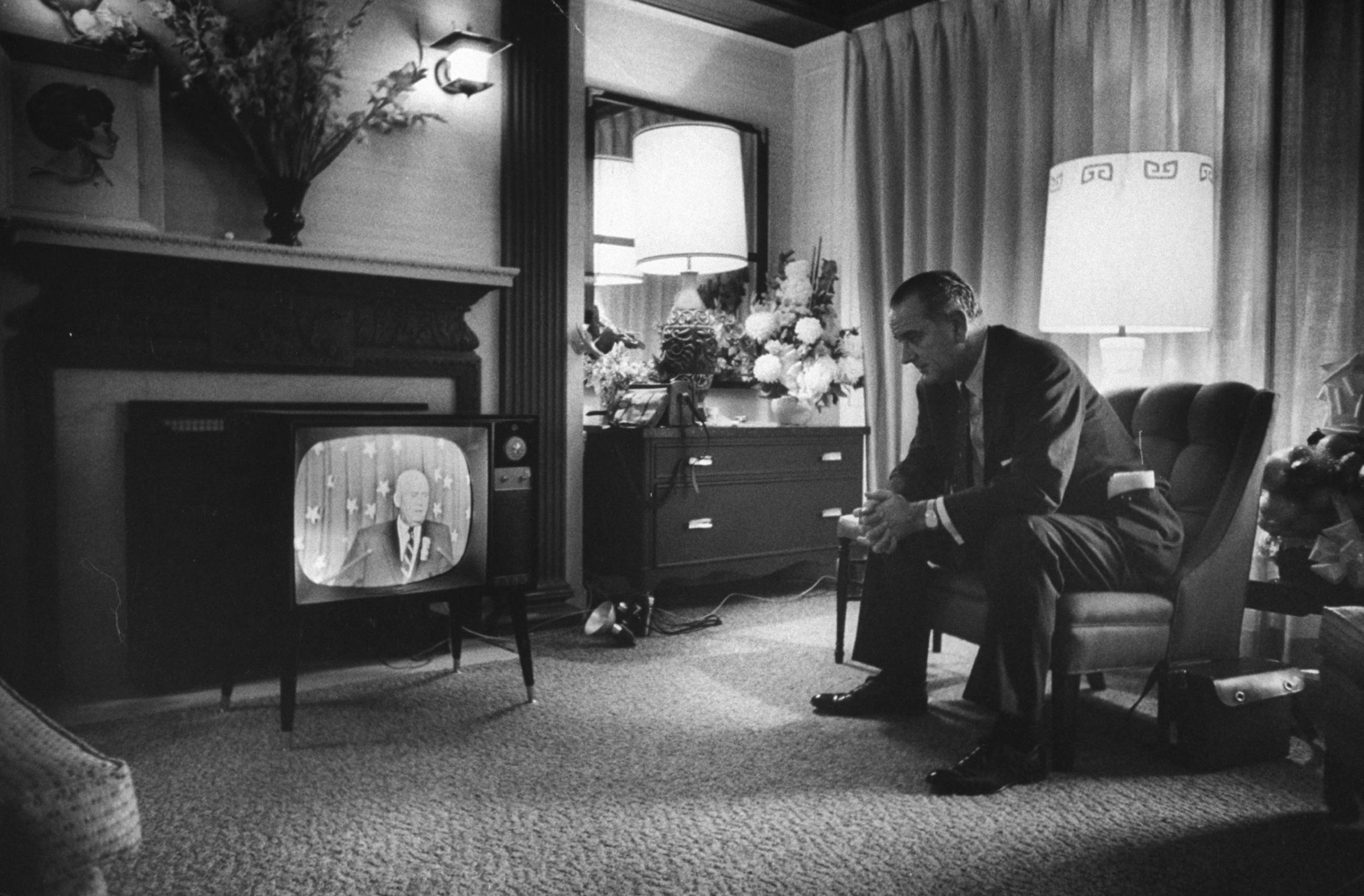

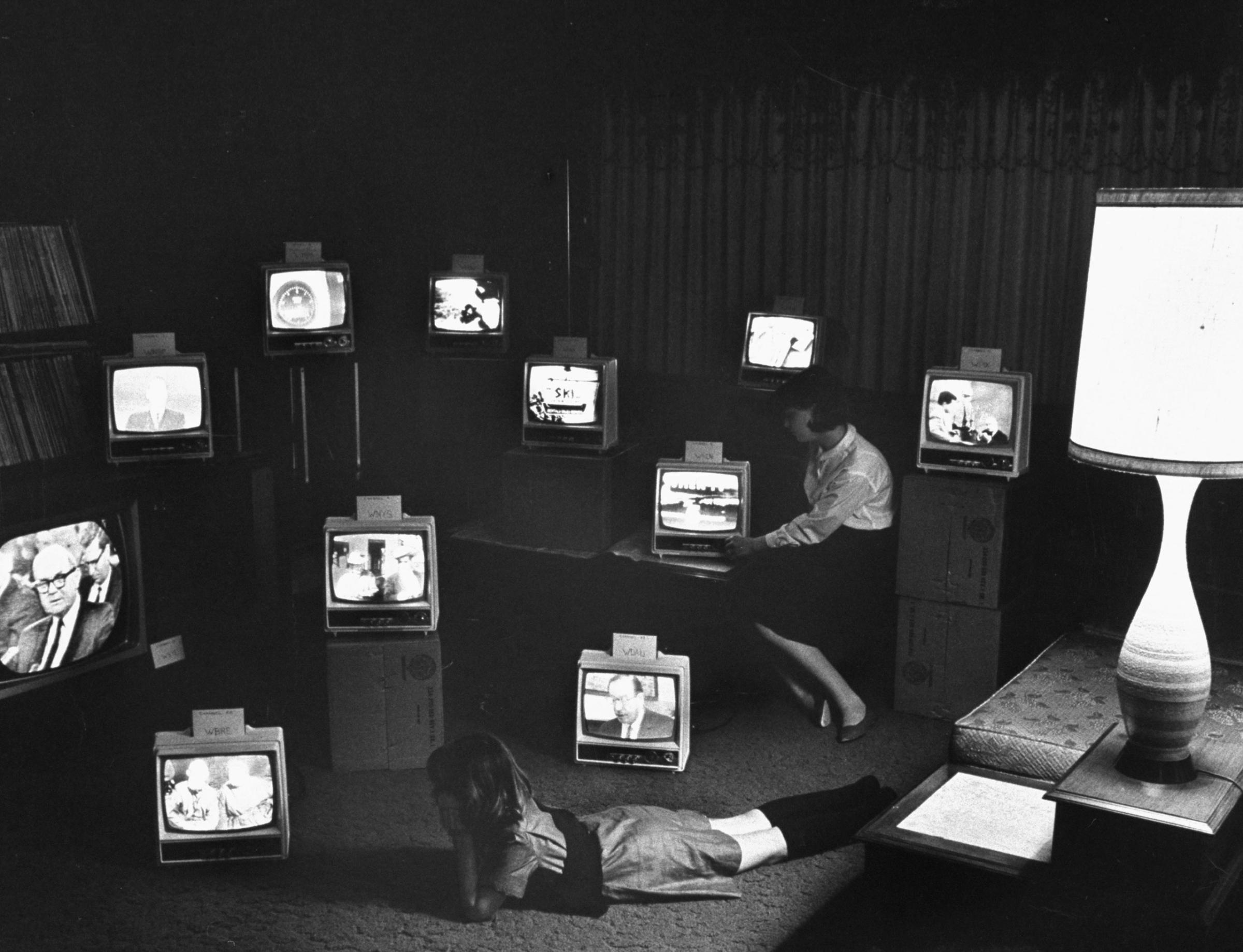

LIFE Watches TV: Classic Photos of People and Their Television Sets

![Jacob A. Malik [Misc.] A group of swimmers at an indoor pool watch the Russian ambassador to the United Nations, Jacob Malik, filibustering in the UN Security Council in 1950.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-07.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Mrs. Malcolm S. Carpenter [& Family] Astronaut Scott Carpenter's wife, Rene, and son, Marc, watch his 1962 orbital flight on TV.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-23.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Diahann Carroll [Misc.];David Frost [Misc.];Diahann Carroll;David Frost Actress Diahann Carroll and journalist David Frost watch themselves on separate talk shows. Carroll and Frost were engaged for a while, but never married.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/141113-vintage-television-photos-28.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com