At first the call for a referendum was bold enough to seem clever, or at least typical of the chutzpah that helped bring Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras to power in Greece in the first place. Its logic was simple. With talks between Greece and its creditors at an impasse, why not give the people a chance to demand a better deal at the ballot box? Would Germany and the other European powers be so callous as to ignore the outcome of a democratic vote? At the very least, the referendum would renew the government’s mandate in its struggle for debt relief.

Germany, however, didn’t flinch. Chancellor Angela Merkel called the bluff on Tspiras’ last-minute gambit with an almost taunting composure. “Before a referendum, as planned, is carried out, we won’t negotiate on anything new at all,” she said on Tuesday. In other words, her response to the threat of a referendum was simple: Knock yourself out.

The Chancellor was not just being stubborn. She had seen the Greek opinion polls suggesting the July 5 referendum would not come out as Tsipras hopes. Although the polls since then have been more mixed, an early majority seemed to emerge this week in favor of a bailout deal, one that would save Greece from abandoning the euro even at the price of higher taxes and more austerity.

On Tuesday evening, tens of thousands of Greeks gathered outside the parliamentary building in Athens to support this position, defying their Prime Minister with calls for Greeks to vote in favor of the deal. Their numbers, to the surprise of many in the crowd, clearly dwarfed the demonstration that had gathered the night before to back Tsipras in rebuffing Greece’s creditors.

The Prime Minister then appeared to lose his nerve. On Tuesday night, he sent a letter to European Finance Ministers asking for another bailout — and apparently conceding to most of their demands for more cuts to the welfare system and higher taxes. The concessions were shocking, as they bowed to many of the terms that Tsipras had so vehemently opposed for months. Nevertheless, it took just a few hours for the European ministers to reject his appeal, surely not without the influence of Germany.

“This government has done nothing since it came into office,” German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said in a speech the next day. “It has only reversed measures. It reneged on previously agreed commitments. It negotiated and negotiated.”

By that point, Greek workers and pensioners had been given a taste of what it could mean to defy their nation’s creditors. The European Central Bank had cut off its emergency cash injections to Greek banks as of Sunday, forcing them to limit the amount of money their clients could withdraw from ATMs. This measure soon caused crowds of elderly Greeks to gather outside banks in Athens to collect at least a portion of their pensions, their outstretched hands providing a grim image of what Greece could turn into without the support of its European peers.

It was not what Tsipras had in mind when he gambled on the referendum. On Friday afternoon, hours before the Prime Minister announced the vote, a senior official in his government had explained the logic of this option to TIME. “This government is determined to keep struggling to persuade the European community that Greece wants to stay in,” said Rania Antonopoulos, the Deputy Minister in charge of combating Greece’s sky-high unemployment. “But we cannot accept conditions that would bring about even more recession.”

Her reasoning was sound. When Greece first accepted austerity in exchange for a bailout in 2010, its creditors badly underestimated the damage it would do to the Greek economy. The country’s GDP wound up shrinking by a quarter over the next five years, creating a recession that has been deeper and more protracted than the U.S. Great Depression. Unemployment also rose to a peak of around 28% in February, with half of young people now jobless in Greece.

Tsipras came to power in January with a promise to change course, and he immediately took his core election promises to Greece’s creditors. The 40-year-old leftist demanded a reduction of his country’s debt, relief to the poor and, above all, no more austerity imposed on Greece from without.

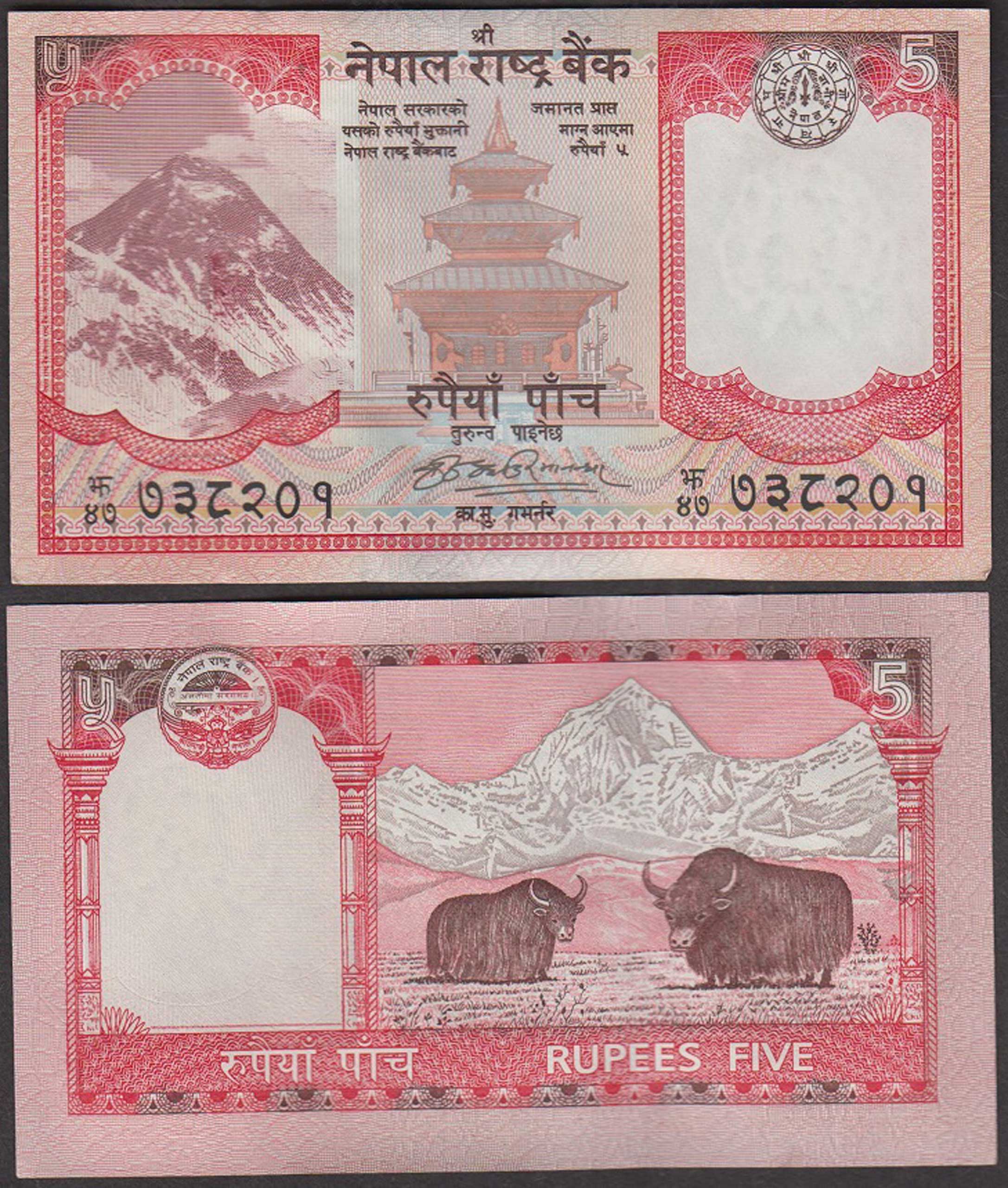

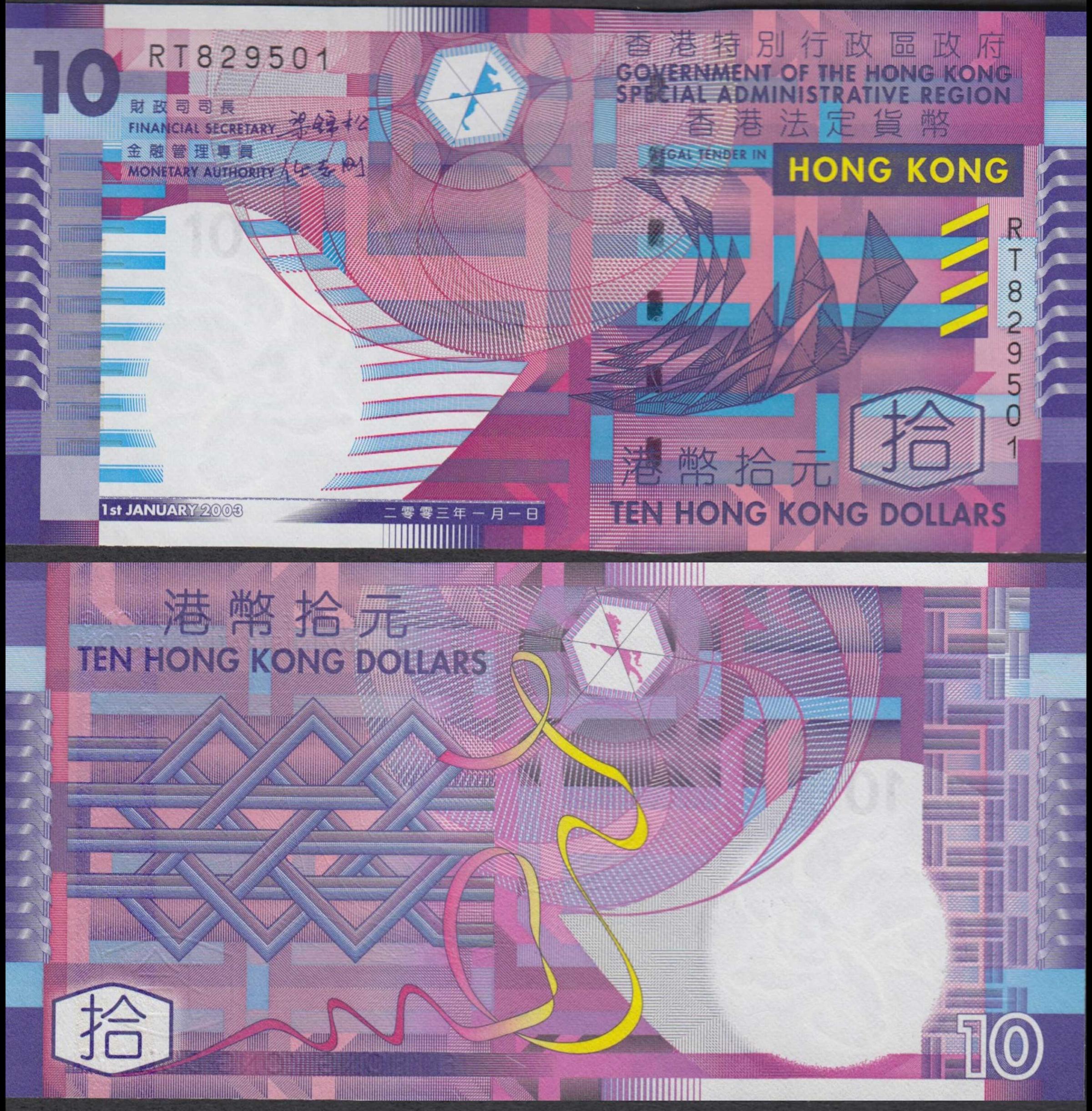

The Most Beautifully Designed Currencies from Around the World

“They are not carelessly engaging in this dialogue,” Antonopoulos says of Tsipras and her other Syriza party leaders. “They are exhausting all possible options before they say, ‘Well, they are kicking us out [of the euro zone]. And if they are kicking us out and we have no other way, then of course we will take it to the people, and the people will decide what is our next move.’”

But Syriza may have overestimated the people’s resolve. Among the party’s core supporters were many of Greece’s poorest citizens, who are ill prepared to face the reality of cash shortages, bank runs and a future without the euro as their currency. In the past few days, the European Union has done its best to demonstrate how painful that reality would be.

“If they vote no, it would be disastrous for the future,” said Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, which along with the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank, makes up the so-called troika of Greece’s creditors. “No would mean they are saying no to Europe,” he told a press conference on Monday.

To many in Greece, this seemed like a blatant attempt to influence the outcome of the referendum, as did the European move to cut the flow of emergency liquidity to Greek banks. The European Central Bank could have kept that assistance alive for just a few more days, allowing banks to stay open at least until the referendum. Instead it chose to turn off the faucet the day after Tsipras called the vote.

Stefanos Manos, a Greek conservative who served as Minister of Finance in the early 1990s, says he’s glad Europe is sending such a clear message. He was among the first to point out how wasteful and inefficient the Greek state had become — and, he says, was considered an “extremist” for doing so. He now sees the referendum as a chance for Greeks to finally accept that he was right — and that perhaps, Merkel is too. “It seems we will come out on top,” Manos says.

The Prime Minister isn’t so sure. In a televised address on Wednesday, Tsipras continued to defy the troika by urging Greeks to vote against the bailout deal — not as a rejection of the European Union or its currency, he said, but as a means of giving him a stronger position in negotiations going forward.

That doesn’t seem like much of an upside when compared to the referendum’s risks. If the people side with Tsipras, he’ll just have to return to the same negotiating table, albeit with a slightly better hand and a revitalized mandate to take a tough position. If voters turn against him, he won’t have any hand to play at all.

Read next: Battle for Greek Votes Under Way as Cash Shortages Bite

Download TIME’s mobile app for iOS to have your world explained wherever you go

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com