In the years since Queen Elizabeth relinquished her last major colony to China in 1997, Hong Kong has frequently commemorated July 1 — the anniversary of the “handover,” as it’s known here — as a day of demonstration, with thousands marching through the sweltering metropolis to air their political grievances. It makes sense: after all, under the political agreement between the U.K. and China, Hong Kong would operate as a quasi-democracy under the umbrella of Chinese rule, and in the democratic imaginary, the right to assembly is axiomatic.

Beyond that, though, there are no real reliable axioms when it comes to democracy in Hong Kong, other than that, for this Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China, democracy itself may be an illusion. Nine months have passed since the beginning of the Umbrella Revolution, when hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers besieged the city’s busiest districts to push for a greater say in how their leader is chosen. But, 12 days ago, Hong Kong lawmakers vetoed the government’s showpiece electoral bill because it required all candidates for the city’s top job to undergo screening by Beijing. It is now highly unlikely that the central government will consider other reform proposals for some time.

That leaves the pro-democracy movement at an impasse. At last year’s July 1 demonstrations — in hindsight, a prologue to the Umbrella Revolution — Hong Kongers called for political upheaval; today, they gather to sit shivah for the stalemate, but also to contemplate their next move.

“This is a day when we restart our campaign — when we ask ourselves what we can do next,” Johnson Cheung, who leads the pro-democratic Civil Human Rights Front, says.

The Hong Kong government is also groping for a way forward. As activists burned an SAR flag outside an official ceremony to mark the 18th anniversary of the handover this morning, Leung Chun-ying, the incumbent chief executive (as the highest official in Hong Kong is called) sought relief in pocketbook issues.

“The government needs the support and cooperation of the entire community if we are to boost the economy and improve the livelihood of the people of Hong Kong,” he told assembled dignitaries.

Underscoring the gulf between the city’s democratic and pro-Beijing camps, Leung also appeared to suggest that a freer political system would not be able to solve Hong Kong’s serious social ills — among them appalling income inequality and sluggish social mobility. “As the experience of some European democracies shows,” he said, “democratic systems and procedures are no panacea for economic and livelihood issues.”

In the mid-afternoon, thousands began to assemble at Victoria Park — a rare greensward in this densely packed city, serving as the march’s starting point and as a traditional place of protest. Many demonstrators carried the colonial-era Hong Kong flag, not as a demonstration of loyalty to Britain but as a defiant assertion of the city’s origins as an international entrepot and the emblem of what they believe to have been a better time. In contrast to the almost carnival atmosphere of previous marches, the mood this year appeared subdued and numbers appeared notably fewer than previous years. Organizers blamed political fatigue.

“At this point, there’s not much we can do politically,” said marcher Thomas Yan, vice chairman of the pro-democracy party People Power. “All we can do now, and in the future, is focus on civic education — on informing the people.”

Marcher Maria Chen agreed that Hong Kong needed to reflect on its next move. “I don’t know what’s next for Hong Kong,” she said. “I hope they listen to us, but I think Hong Kong needs to figure it out for itself. Our future should lie in our hands.”

Less than a hundred meters up Hennessy Road, police officers stood between marchers and a group of pro-Beijing demonstrators staging a counter rally. As tensions flared and verbal barbs were traded, the pro-Beijing camp turned up the volume on its loudspeaker and blared the Chinese national anthem — a melody that Hong Kong soccer supporters have recently taken to jeering at international matches.

“After the democrats vetoed the [government’s electoral bill], we realized we needed a new direction,” Agnes Chow, a senior member of the student activist group Scholarism, told TIME earlier. “We’re in a very passive position politically, because any attempt at constitutional reform is going to be led by the central government in Beijing.”

Passive is an interesting choice of word, coming from someone who was at the forefront of the Umbrella Revolution — the largest and most violent political demonstration in China since the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Chow is uncertain what will come next, but is keen to note that tensions continue to mount.

It isn’t just rhetoric. Late Sunday night, Joshua Wong, the outspoken 18-year-old activist who has emerged as a figurehead of Hong Kong’s democratic zeitgeist, was leaving a movie with his girlfriend when an unknown assailant “grabbed [his] neck, and punched [his] left eye,” he tells TIME. Earlier that evening and mere blocks away, a group of “localists” — those in favor of far greater Hong Kong autonomy, even complete independence, from China — staged a rally to protest the politically and culturally provocative presence of street musicians from mainland China. Violence quickly erupted between the localists and members of pro-China groups, who turned up to support the musicians.

“My own view is that this is predictable,” David Zweig, a professor of social sciences at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, tells TIME. “We can see a shift from civil disobedience and towards more violence. People are becoming more frustrated with the fact that Beijing has made no concessions.”

Those on the march appeared to understand this political reality. “So long as the Beijing government is insisting we don’t have a way out, legislative reform can hardly happen,” Ken Wu, a 27-year-old social worker, told TIME.

The SAR government is not in a conciliatory mood either. During his address at today’s official ceremony, Chief Executive Leung spoke of the “serious threats to social order and the rule of law” posed by last year’s Umbrella Revolution, and warned that the city’s development would be seriously impeded if democratic legislators continued to block the government’s legislative agenda.

“All we ask is for the citizens of Hong Kong to respect the system,” Po Chun-chung, of the pro-Beijing Defend Hong Kong Campaign, said, as the march went by. Many demonstrators, tired of what they see as the mainland’s encroachment on the city’s autonomy, and its reneging on promises of genuine democracy, would like to ask Beijing to do the same.

“The [mainland] Chinese have gotten dirtier and dirtier,” said Eric, a 32-year-old protester. “They get their hands into our lives and we don’t have any way to fight back. This is the only way.”

—With reporting by Joanna Plucinska and Alissa Greenberg/Hong Kong

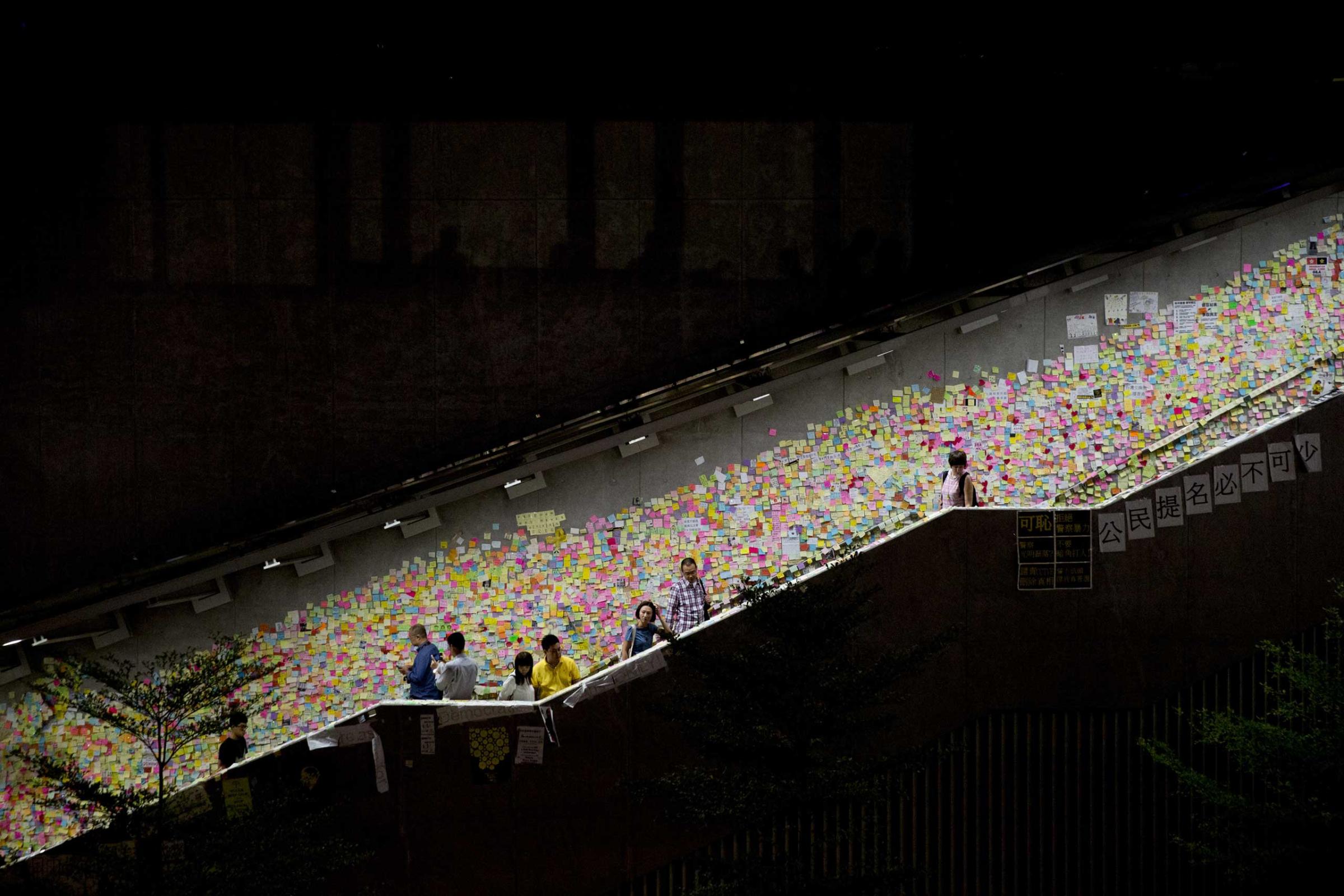

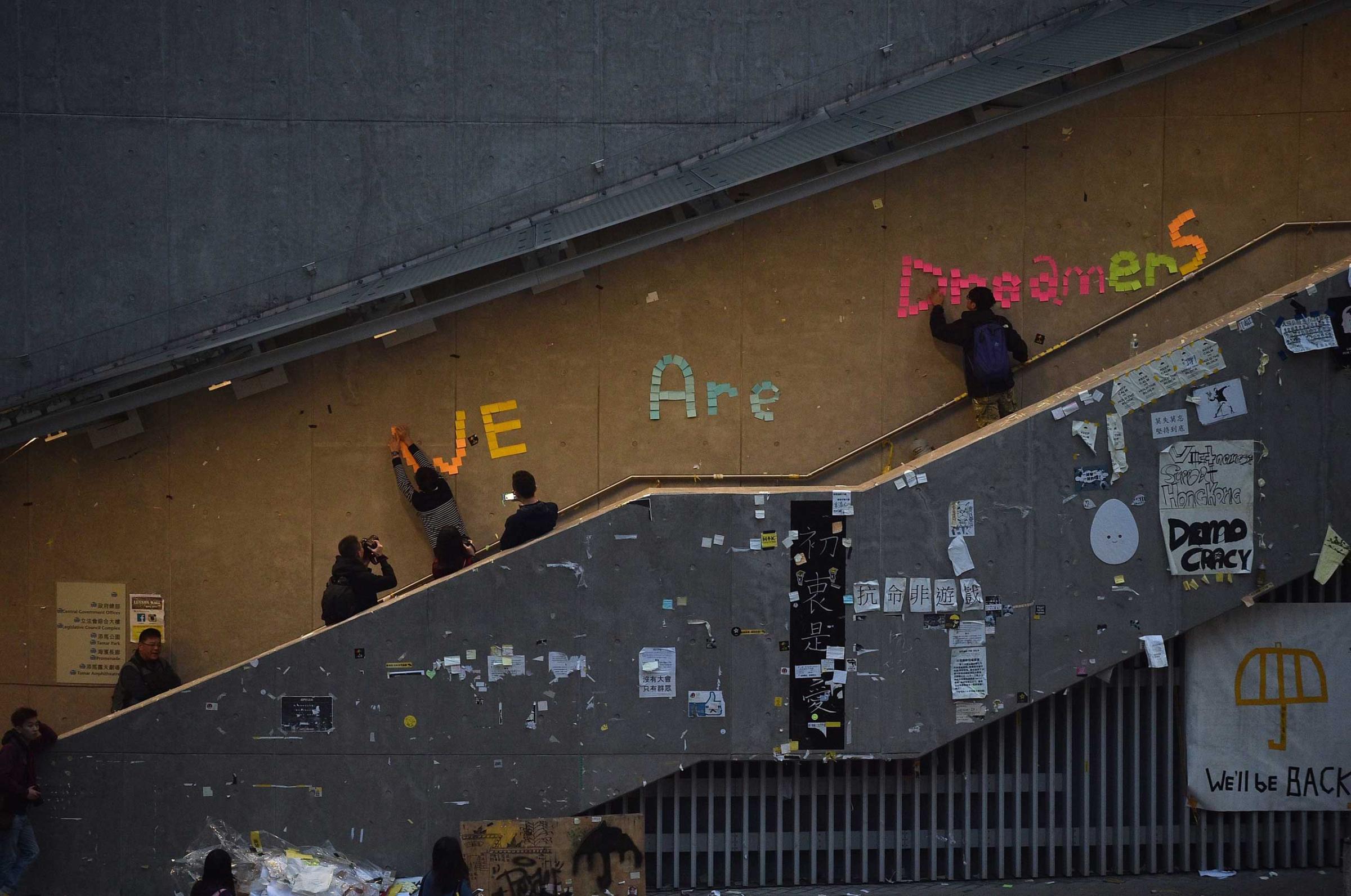

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com