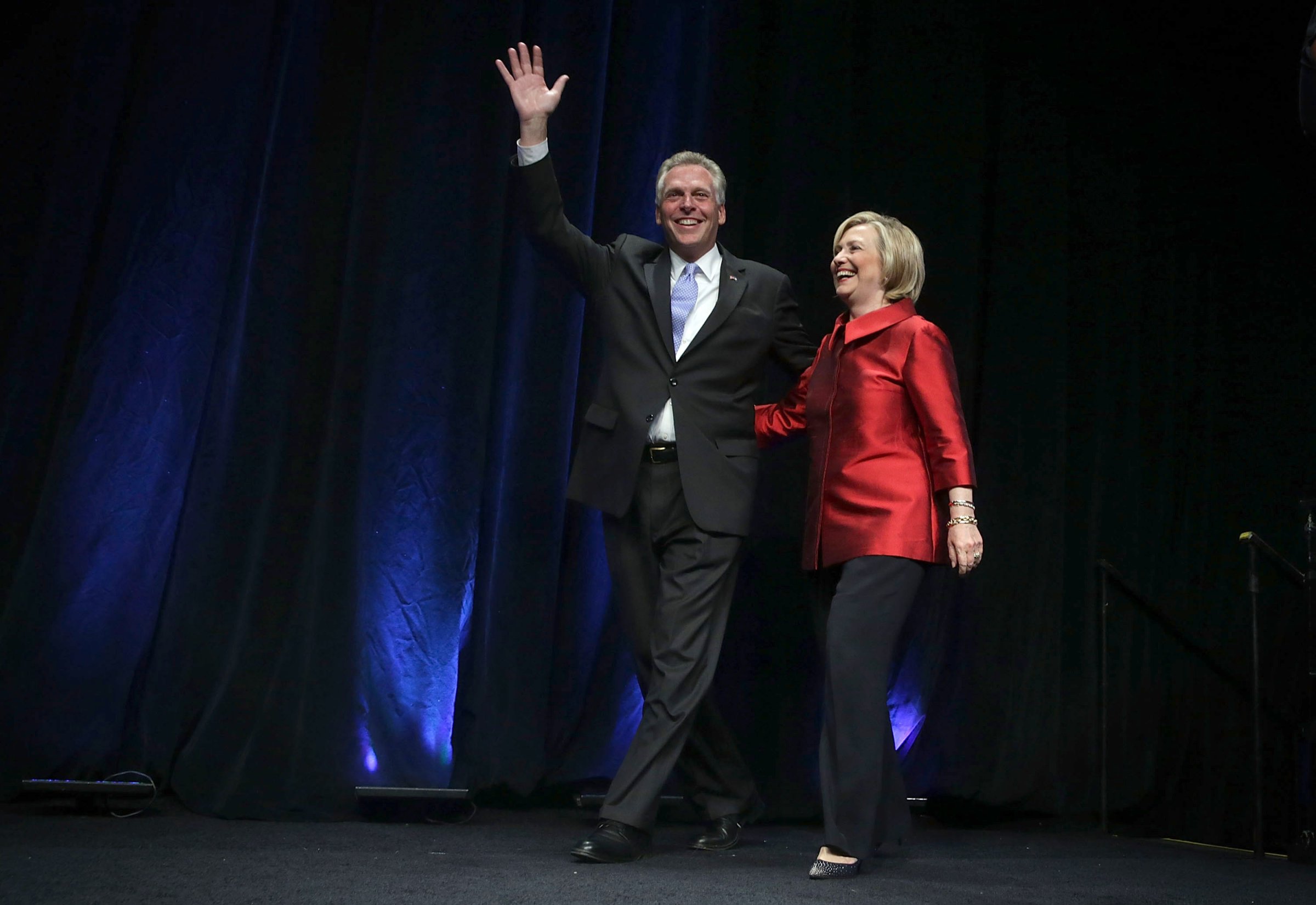

When Terry McAuliffe stormed the stage at a Virginia Democrats’ rally at George Mason University on Friday, Hillary Clinton followed on with an arm around her decades-long friend and political partner.

“I’ll tell you an honest story. When we’re on vacation, come about 6 o’clock at night, I’m ready for a cold beer,” McAuliffe told the crowd of 1,800 supporters, heaping unscripted love on Clinton as she stood smiling by his side. “I don’t go looking for Bill Clinton. I go looking for Hillary Clinton. Because she’s a lot more fun than Bill Clinton is, and I love him too!”

“Woah!” said Clinton, taking the microphone and matching McAuliffe, gush for gush. “I love your governor and I love your first lady.”

Clinton and McAuliffe shared more than just a stage and some kind words on Friday: they are now splitting the spoils of his successful 2013 race for governor of Virginia. Now in its third month, Clinton’s campaign for president has adopted key strategic lessons from McAuliffe’s gubernatorial race, including the finer details of a data-driven field organization focused on turning out the Democratic base and unmarried women, leaning into progressive Democratic positions and hiring many of the same staff members that helped McAuliffe win the governor’s mansion. And Democrats say that McAuliffe’s 2013 victory sets the stage for the state to go blue in the 2016 general election, when Hillary Clinton is the likely candidate.

Bill and Hillary Clinton took a keen interest in the 2013 race—and campaign manager Robby Mook—beyond their role as longtime friends of McAuliffe, her 2008 presidential campaign chairman and his 1996 presidential co-chair. McAuliffe’s staffers recall their candidate receiving excited late-night calls from Bill with stump speech pointers and campaign advice.

Former McAuliffe aides are quick to say that their energy in 2013 was focused on getting their man to the governor’s house. But since then, the victorious McAuliffe campaign has become an ex post facto lab experiment for Clinton’s current bid for the White House.

A purple state that is trending blue, Virginia bears similarities to the general American electorate: its nonwhite population is growing and its voters are increasingly adopting liberal stances social issues. The swing state offered an ideal test run for the Clinton operation, combining vast rural tracts with midsized cities and expansive suburbs.

More alike than the voters, though, are the ethos, spirit and strategy of the campaigns themselves, much of it coming from Mook, the general on McAuliffe’s campaign who is now leading Clinton’s army.

“I can’t think of a state campaign where the esprit was as good as it was in Terry’s campaign. It was not just a minimal amount of backbiting: there was no backbiting,” said Geoff Garin, the pollster for McAuliffe’s campaign who is now working on the pro-Clinton super PAC, Priorities USA Action. “And part of Robby’s strength as a leader is he does get people engaged and pulling in the same direction.”

Central to McAuliffe’s campaign was his embrace of staunch Democratic positions on gay rights, abortion, gun control and healthcare a hard play for the Democratic base in Virginia that capitalized on the left-shifting electorate in his 2013 race for governor. Clinton has likewise embraced gay marriage, making it a central platform of her campaign messaging this year, just as public support has reached an all-time high. And she has fervently called for action on gun control at a time when a majority of Americans are in favor of universal background checks. Both have also embraced the Affordable Care Act, the controversial law that is growing in acceptance among the general populace but remains anathema to Republicans.

Those progressive positions succeeded in energizing the Democratic base without alienating Virginia moderates, also a central organizing tack of Clinton’s campaign.

To turn out Democrats, McAuliffe adopted and expanded the Obama grassroots vision, bringing on a huge staff of field organizers and signed up volunteers to knock on doors and work the phones from the very beginning of his campaign. Clinton hired about 100 field staff across all 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia for a two-month intensive effort after her announcement, and at least half the staff remains on the payroll.

Both the 2013 and the current presidential campaigns will rely on an army of volunteers, a flurry of commit-to-vote cards, targeted door-to-door canvassing and plenty of money to fund the efforts.

“The hallmarks of what Robby did in Virginia, and what he’s building now, is that the organizing occurred on the ground very early in the campaign,” Garin said.

Beyond Mook, a bevy of key McAuliffe alumni have migrated to the Clinton camp. Brynne Craig, Clinton’s deputy political director, was the political director on McAuliffe’s campaign. Josh Schwerin, a spokesman on Clinton’s campaign, was the press secretary in the 2013 gubernatorial race. And some of the key players organizing Hillary’s large ground operations in Iowa are former McAuliffe staffers as well, including Clinton caucus director Michael Halle and organizing director Michelle Kleppe. In fact, when Clinton announced on April 12, about a dozen McAuliffe veterans were already on the ground in Iowa, having arrived quietly days before to help lay the groundwork for her campaign in the first-in-the-nation caucus state.

Despite the talk of focusing on the race at hand, it was clear that whatever happened during the gubernatorial campaign would matter in 2016.

“Everybody knew Robby was in the running for that job” of running the top 2016 Democratic operation, said someone close to the McAuliffe campaign. “But there was a real sense of cream rising to the top broadly: nobody could do well if this campaign didn’t go well.”

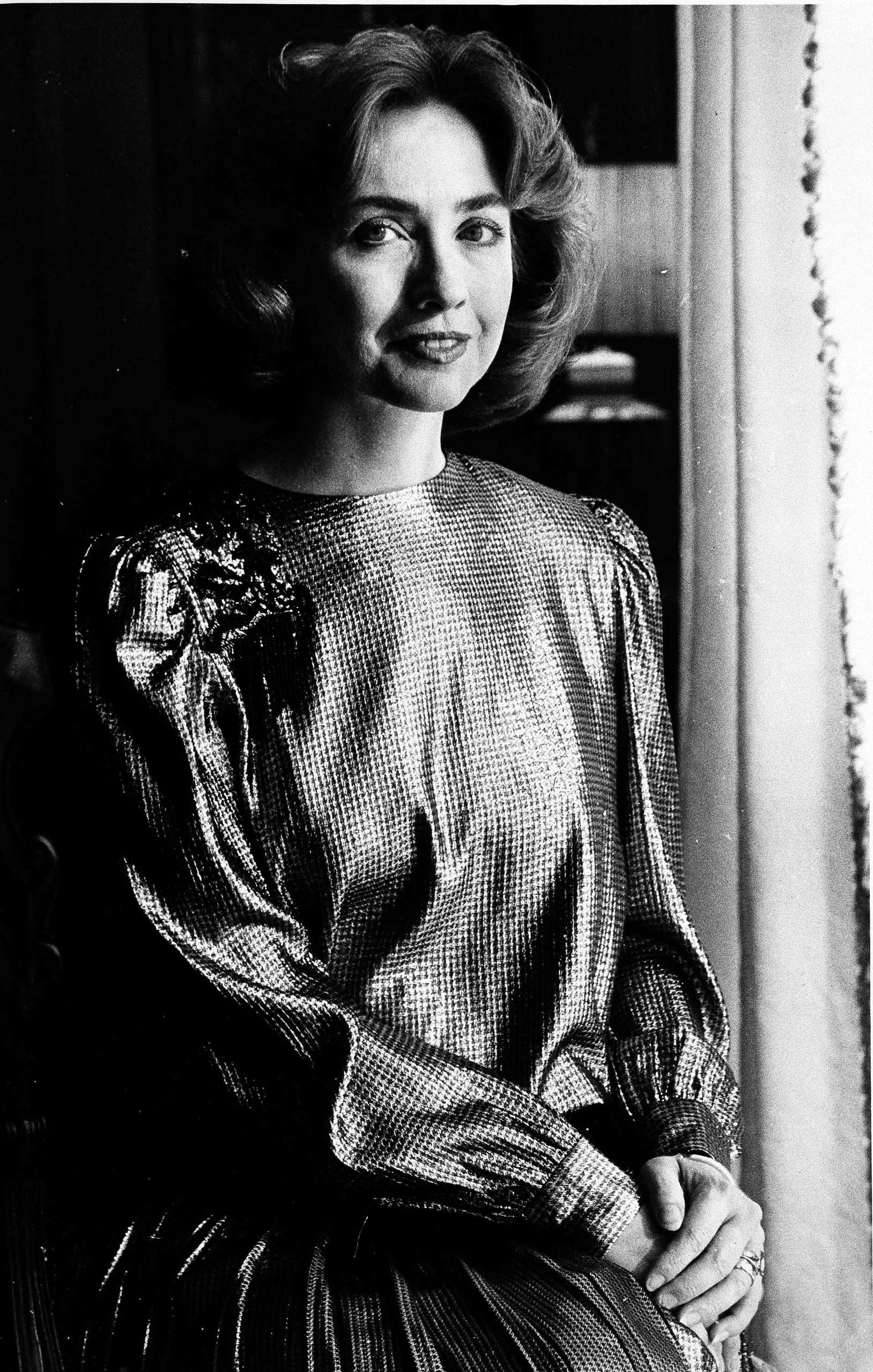

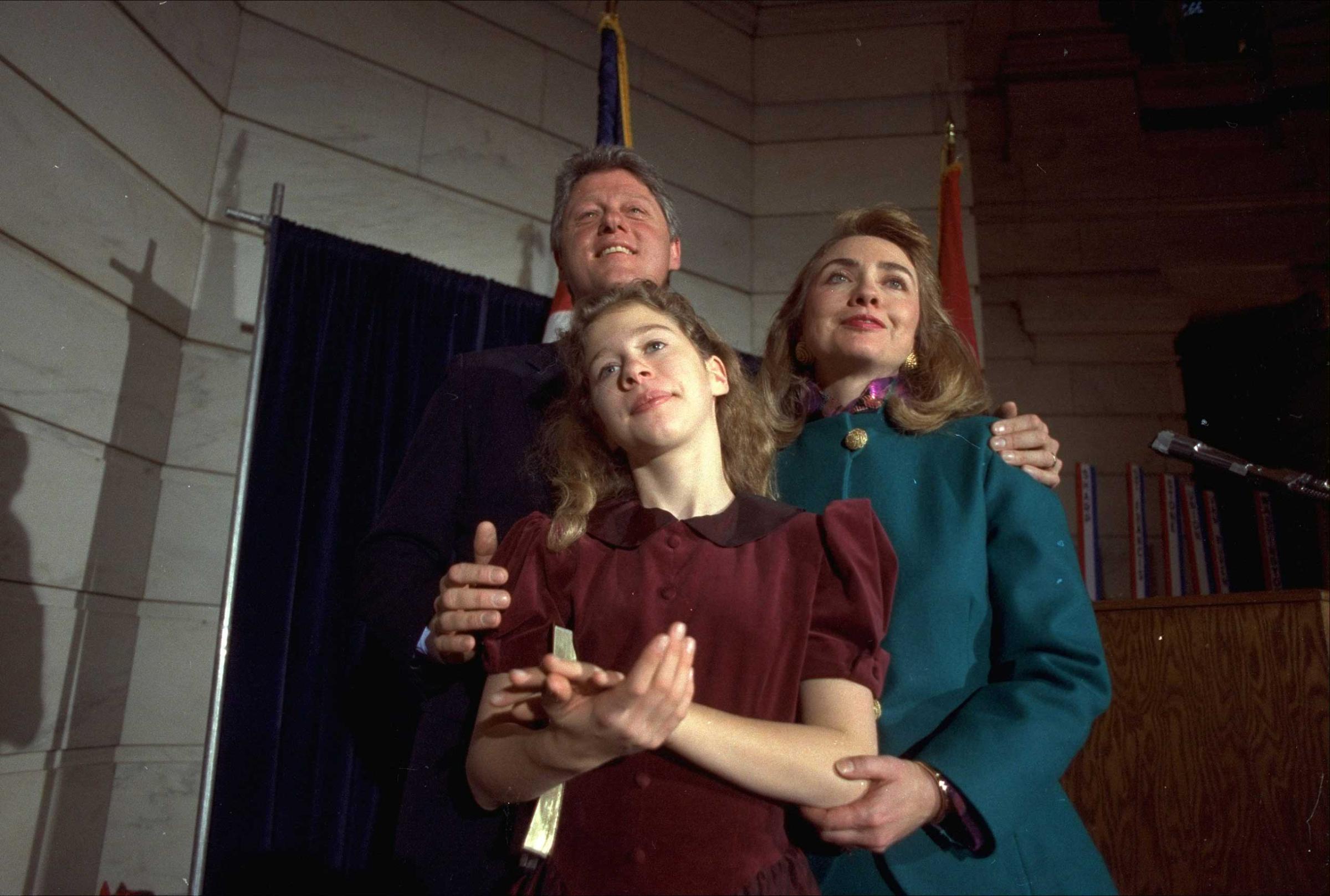

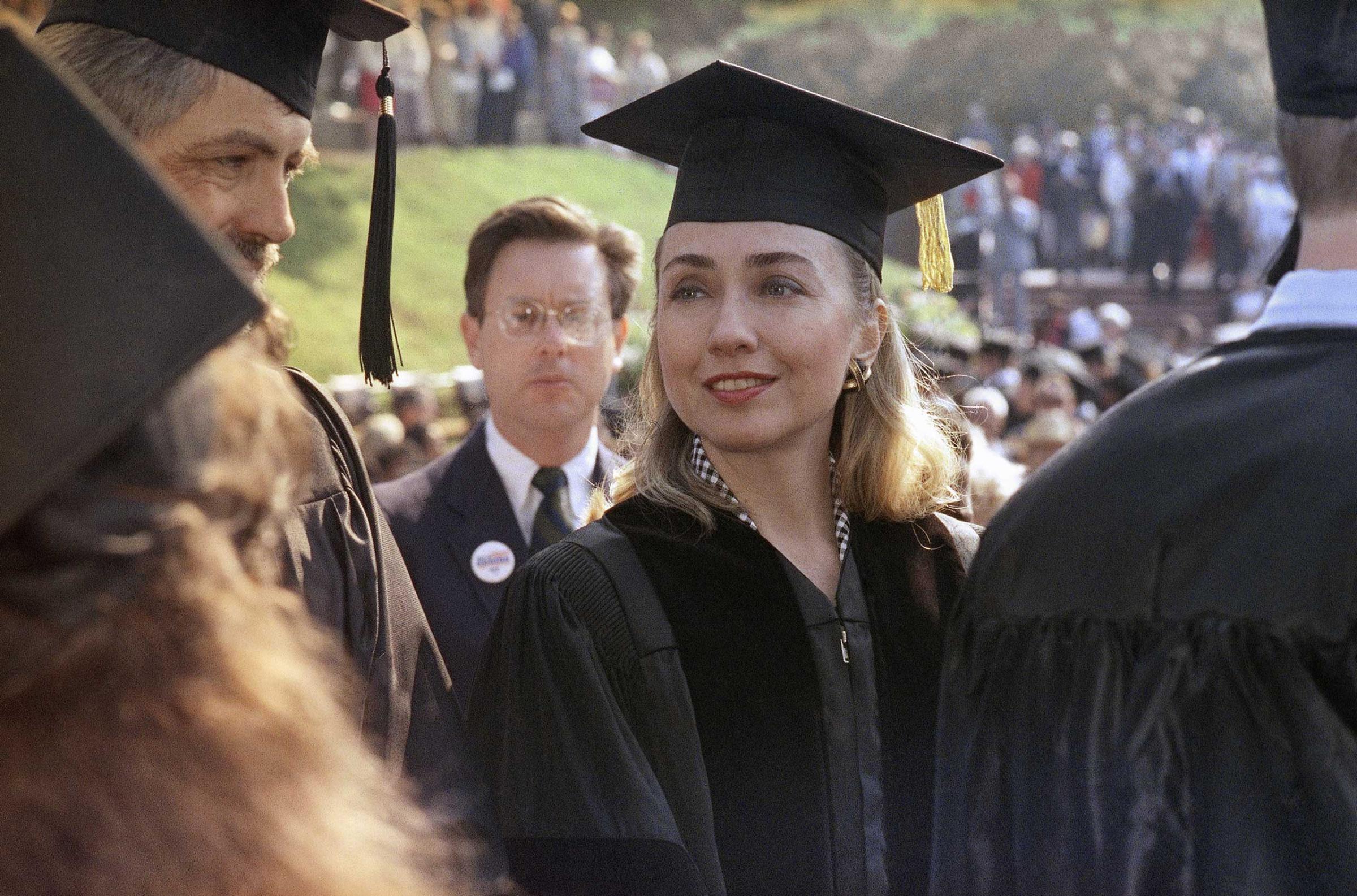

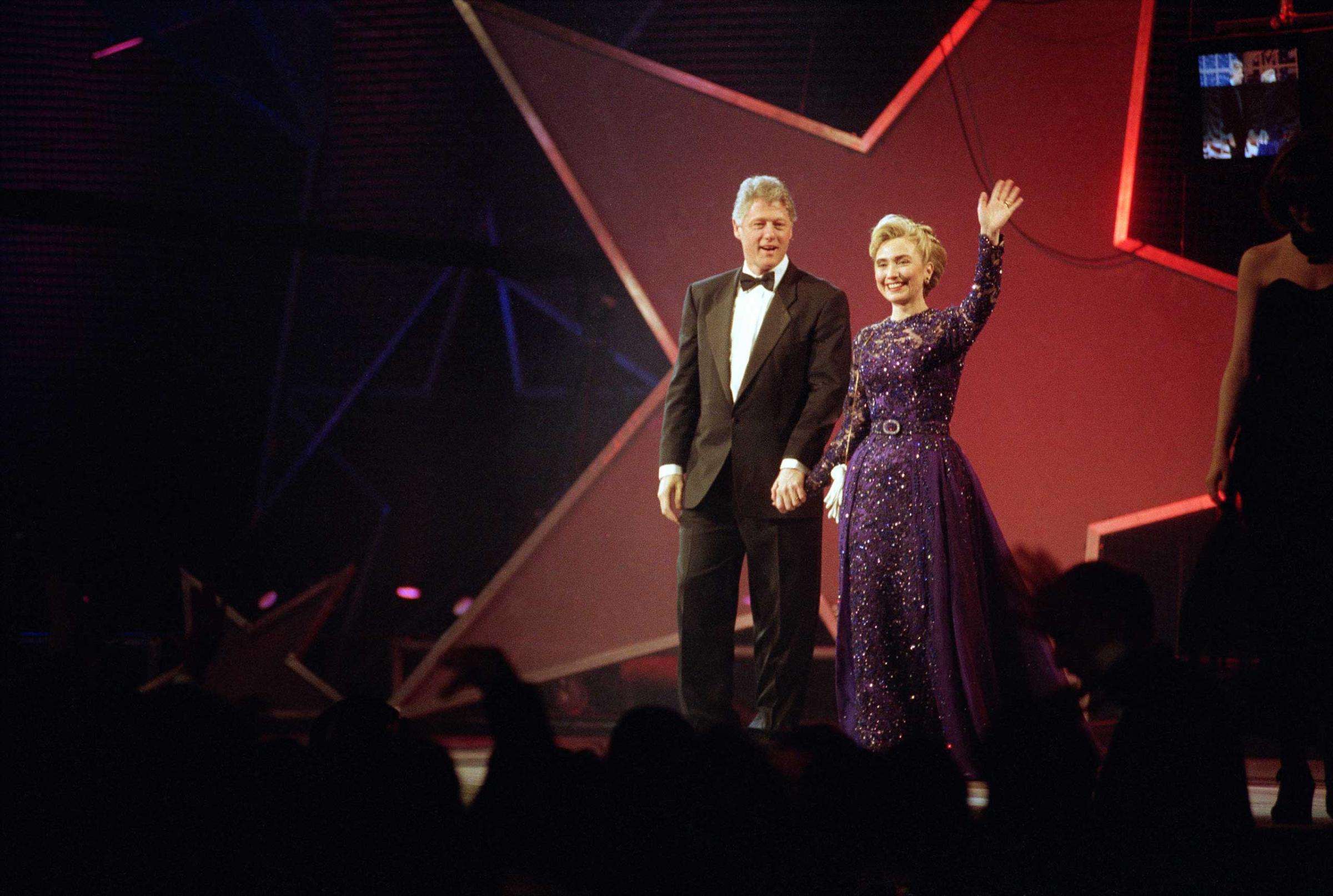

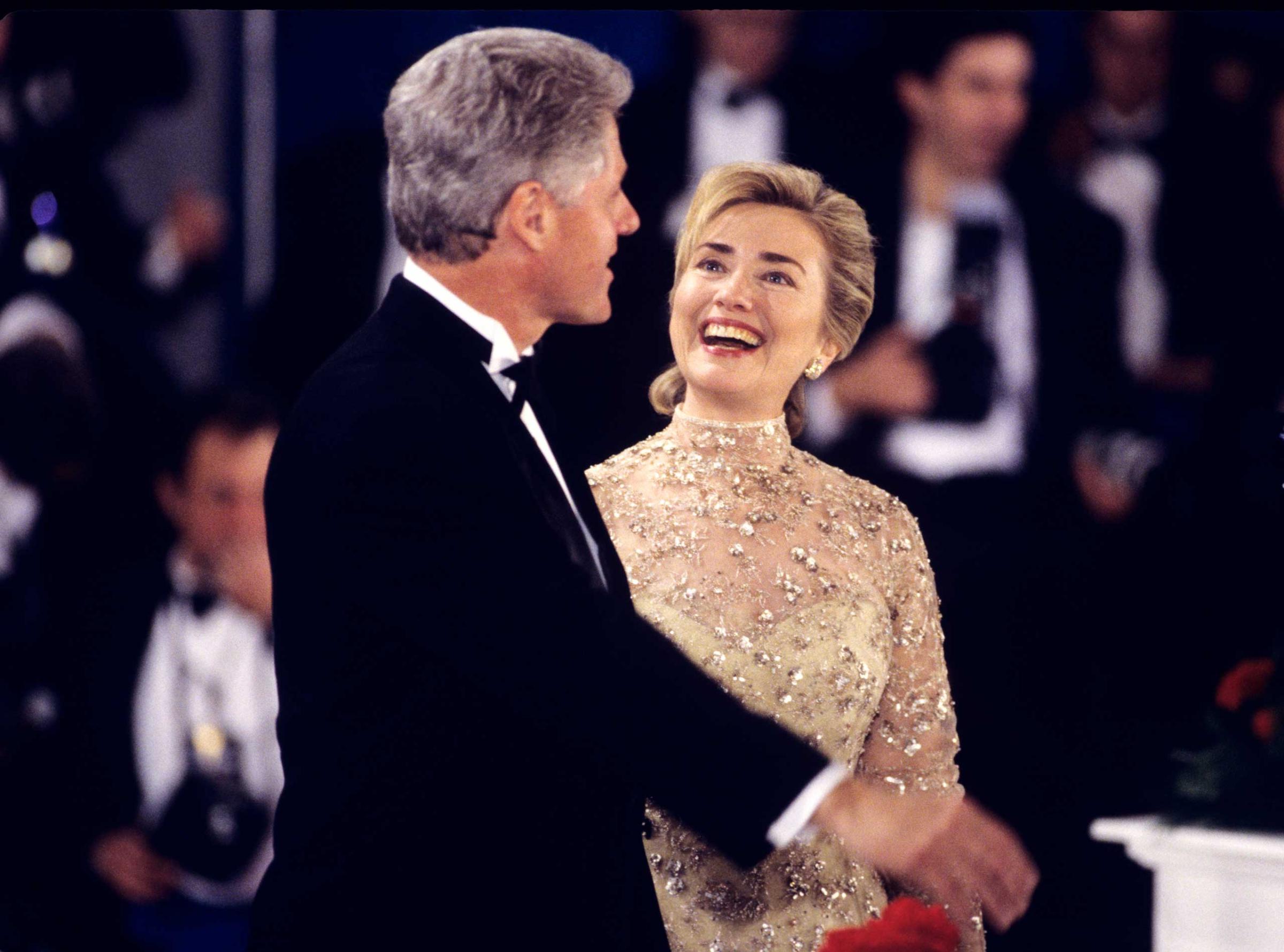

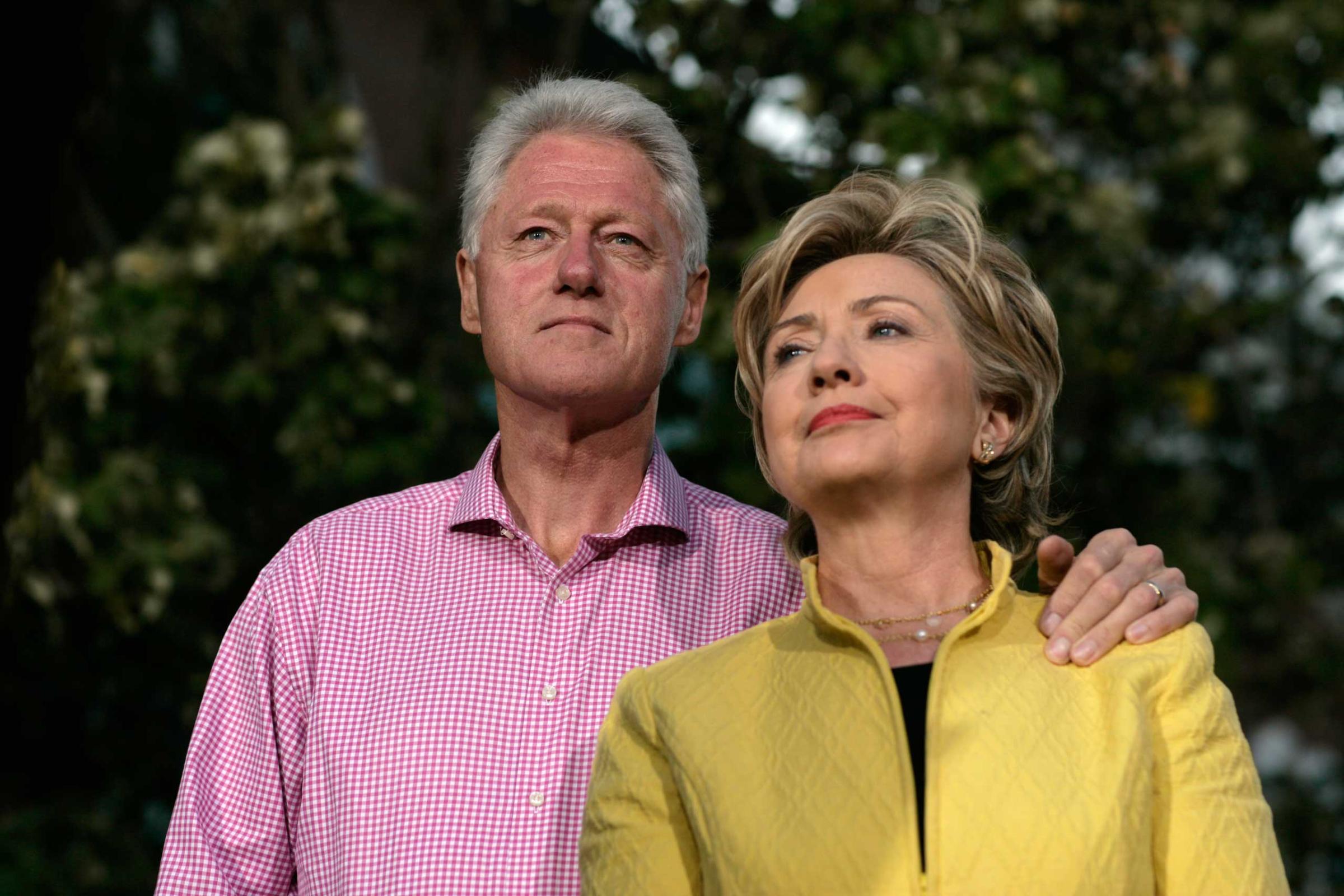

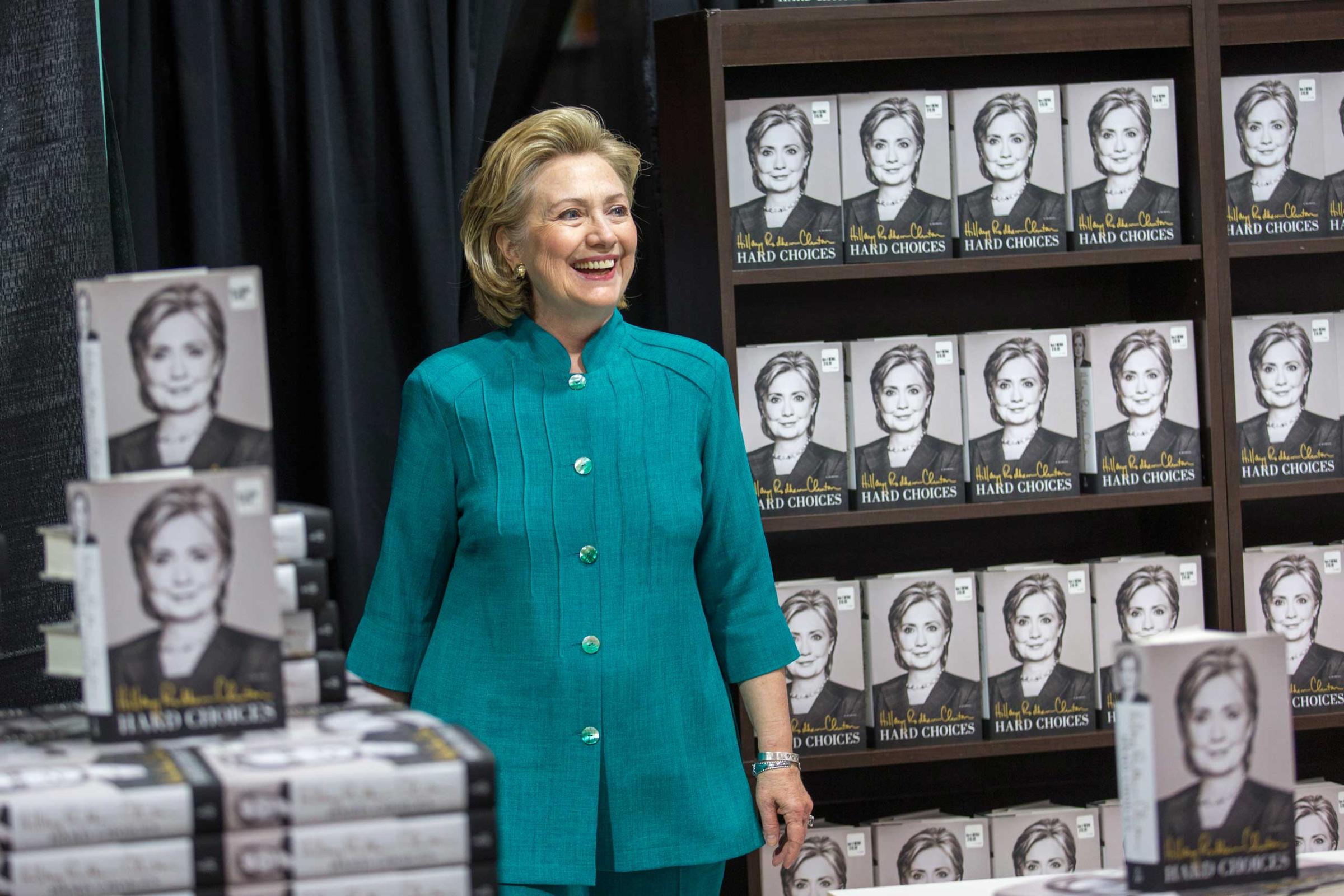

See Hillary Clinton's Evolution in 20 Photos

Clinton and McAuliffe have had long and closely entwined careers. McAuliffe put up $1.35 million as collateral on Clinton’s mortgage to buy their home in Chappaqua, N.Y. The Clintons, in turn, have provided McAuliffe a large network for his business and political enterprises.

And together, they are magnets for controversy. On the campaign trail in Virginia in 2013, McAuliffe’s strategy was to sidestep the accusations of shady business deals, including a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation of an electric car company he founded. Clinton, similarly, has herself largely tried to skirt questions about the Clinton Foundation and her private email server during her time as Secretary of State. Both are reflection of Mook’s long-held strategy “to keep the principals in their box and away from making mistakes, giving the rest of the campaign room to do its job,” says a McAuliffe confidant.

“People who have a lot of history—that needs to be managed when you’re messaging to voters,” said another former McAuliffe campaign staffer. “The campaign in Virginia relied on us not taking the bait on fights on anything in his public record. And you may see that with Clinton campaign.”

McAuliffe, for his part, acknowledged as much in an interview with TIME earlier this year, crediting Mook for keeping his campaign’s eye on the prize.

“In Clinton world there are a lot of friends, a lot of people who want to help, and what he is able to do is direct all of their energy in a positive way. He can make sure campaign staff can do their jobs without losing focus,” McAuliffe said.

McAuliffe’s victory was due in no small part to unmarried women voters, whom he won by a huge margin of 67% to just 25% for Cuccinelli. McAuliffe blasted ads during the campaign framing Cuccinelli as a right-wing zealot on contraception and abortion issues. That demographic is crucial for Clinton, who tops unmarried woman over a generic Republican candidate with 66% of the vote to 29%, according to a recent Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research poll.

For all the similarities, there are fundamental differences in the two campaigns. McAuliffe outraised his opponent for the governor’s office by about $15 million—a large margin for a gubernatorial race that Clinton is unlikely to replicate in 2016.

“It’s easy to be the smartest guy in the room when you are able to spend at least $15 million more than your opponent in a statewide race,” said a former advisor to McAuliffe opponent Ken Cuccinelli. “One of the other major differences between 2013 and 2016 is that the huge funding disparity between the two candidates won’t be present again.”

Update: A Clinton campaign spokesperson said campaign manager Robby Mook has no recollection of meeting the Clintons after Gov. McAuliffe’s inauguration. That reference has been removed.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com